13.3 Gender Development

Pink and blue baby outfits illustrate how cultural norms vary and change. “The generally accepted rule is pink for the boy and blue for the girl,” declared the Earnshaw’s Infants’ Department in June of 1918 (Frassanito & Pettorini, 2008). “The reason is that pink being a more decided and stronger color is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girls.”

13-

We humans share an irresistible urge to organize our worlds into simple categories. Among the ways we classify people—

Our gender is the product of the interplay among our biological dispositions, our developmental experiences, and our current situations (Eagly & Wood, 2013). Before we consider that interplay in more detail, let’s take a closer look at some ways that males and females are both similar and different.

Similarities and Differences

13-

Whether male or female, each of us receives 23 chromosomes from our mother and 23 from our father. Of those 46 chromosomes, 45 are unisex. Our similar biology helped our evolutionary ancestors face similar adaptive challenges. Both men and women needed to survive, reproduce, and avoid predators, and so today we are in most ways alike. Tell me whether you are male or female and you give me no clues to your vocabulary, happiness, or ability to see, hear, learn, and remember. Women and men, on average, have comparable creativity and intelligence and feel the same emotions and longings. Our “opposite” sex is, in reality, our very similar sex.

But in some areas, males and females do differ, and differences command attention. Some much talked-

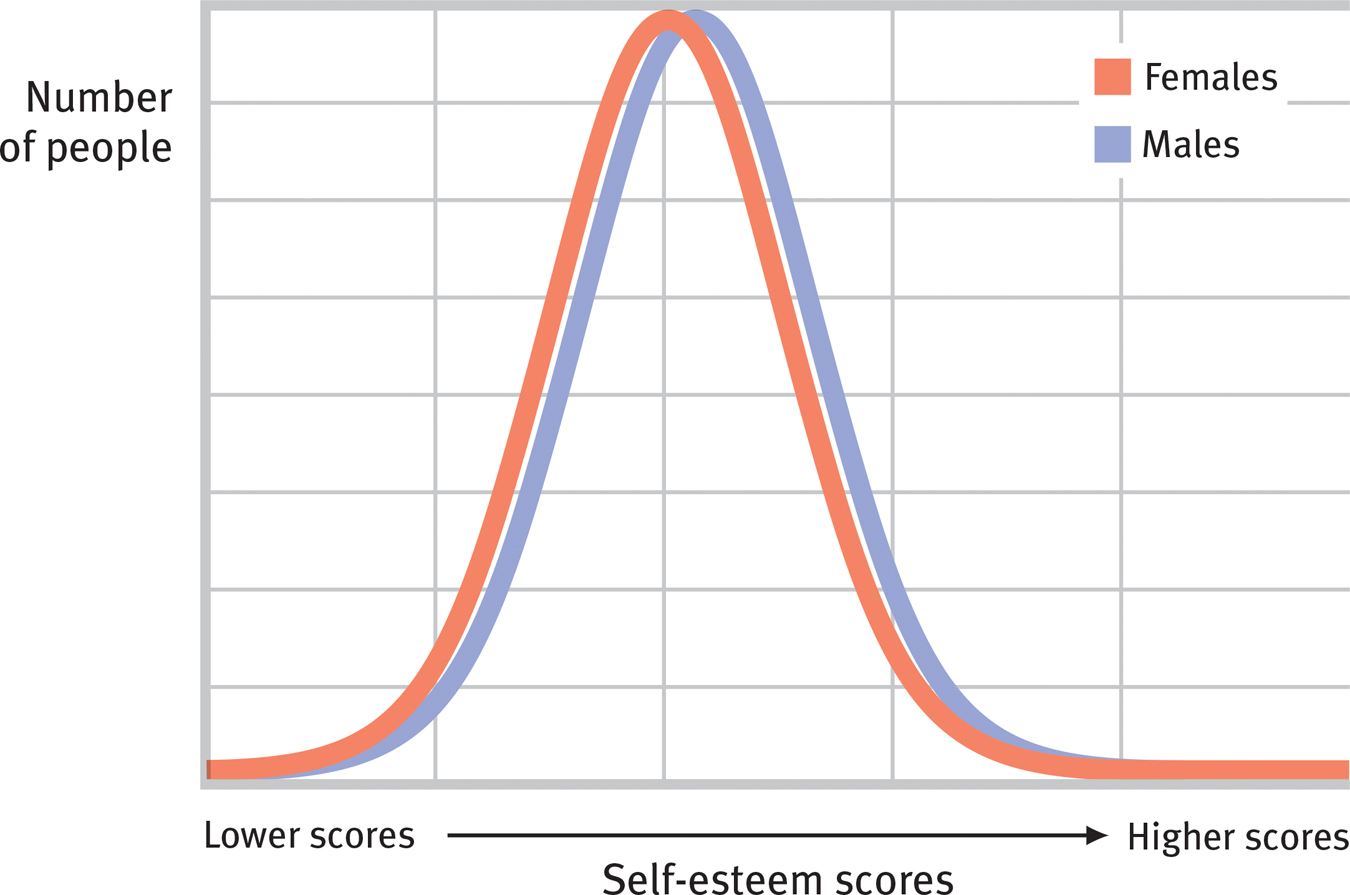

Figure 13.4

Figure 13.4Much ado about a small difference in self-

Let’s take a closer look at three areas—

AggressionTo a psychologist, aggression is any physical or verbal behavior intended to hurt someone physically or emotionally. Think of some aggressive people you have heard about. Are most of them men? Men generally admit to more aggression. They also commit more extreme physical violence (Bushman & Huesmann, 2010). In romantic relationships between men and women, minor acts of physical aggression, such as slaps, are roughly equal—

Laboratory experiments have demonstrated gender differences in aggression. Men have been more willing to blast people with what they believed was intense and prolonged noise (Bushman et al., 2007). And outside the laboratory, men—

Here’s another question: Think of examples of people harming others by passing along hurtful gossip, or by shutting someone out of a social group or situation. Were most of those people men? Perhaps not. Those behaviors are acts of relational aggression, and women are slightly more likely than men to commit them (Archer, 2004, 2007, 2009).

Social PowerImagine walking into a job interview. You sit down and peer across the table at your two interviewers. The unsmiling person on the left oozes self-

Which interviewer is male?

If you said the person on the left, you’re not alone. Around the world, from Nigeria to New Zealand, people have perceived gender differences in power (Williams & Best, 1990). Indeed, in most societies men do place more importance on power and achievement and are socially dominant (Schwartz & Rubel-

- When groups form, whether as juries or companies, leadership tends to go to males (Colarelli et al., 2006). And when salaries are paid, those in traditionally male occupations receive more.

- When people run for election, women who appear hungry for political power more than their equally power-hungry male counterparts experience less success (Okimoto & Brescoll, 2010). And when elected, political leaders usually are men, who held 78 percent of the seats in the world’s governing parliaments in 2014 (IPU, 2014).

Men and women also lead differently. Men tend to be more directive, telling people what they want and how to achieve it. Women tend to be more democratic, more welcoming of others’ input in decision making (Eagly & Carli, 2007; van Engen & Willemsen, 2004). When interacting, men have been more likely to offer opinions, women to express support (Aries, 1987; Wood, 1987). In everyday behavior, men tend to act as powerful people often do: talking assertively, interrupting, initiating touches, and staring. And they smile and apologize less (Leaper & Ayres, 2007; Major et al., 1990; Schumann & Ross, 2010). Such behaviors help sustain men’s greater social power.

Women’s 2011 representations in national parliaments ranged from 13 percent in the Pacific region to 42 percent in Scandinavia (IPU, 2014).

Social ConnectednessWhether male or female, we all have a need to belong, though we may satisfy this need in different ways (Baumeister, 2010). Males tend to be independent. Even as children, males typically form large play groups. Boys’ games brim with activity and competition, with little intimate discussion (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). As adults, men enjoy doing activities side by side, and they tend to use conversation to communicate solutions (Tannen, 1990; Wright, 1989). When asked a difficult question—

Question: Why does it take 200 million sperm to fertilize one egg? Answer: Because they won’t stop for directions.

Females tend to be more interdependent. In childhood, girls usually play in small groups, often with one friend. They compete less and imitate social relationships more (Maccoby, 1990; Roberts, 1991). Teen girls spend more time with friends and less time alone (Wong & Csikszentmihalyi, 1991). In late adolescence, they spend more time on social-

Brain scans suggest that women’s brains are better wired to improve social relationships, and men’s brains to connect perception with action (Ingalhalikar et al., 2013). The communication style gender difference is apparent even in electronic communication. In one New Zealand study of student e-

Do such findings mean that women are just more talkative? No. In another study, researchers counted the number of words 396 college students spoke in an average day (Mehl et al., 2007). Not surprisingly, the participants’ talkativeness varied enor-

The words we use may not peg women or men as more talkative, but those words do open windows on our interests. Worldwide, women’s interests and vocations tilt more toward people and less toward things (Eagly, 2009; Lippa, 2005, 2006, 2008). In one analysis of over 700 million words collected from Facebook messages, women used more family-

In the workplace, women are less often driven by money and status and more apt to opt for reduced work hours (Pinker, 2008). In the home, they are five times more likely than men to claim primary responsibility for taking care of children (Time, 2009). Women’s emphasis on caring helps explain another interesting finding: Although 69 percent of people have said they have a close relationship with their father, 90 percent said they feel close to their mother (Hugick, 1989). When searching for understanding from someone who will share their worries and hurts, people usually turn to women. Both men and women have reported their friendships with women as more intimate, enjoyable, and nurturing (Kuttler et al., 1999; Rubin, 1985; Sapadin, 1988).

Bonds and feelings of support are even stronger among women than among men (Rossi & Rossi, 1993). Women’s ties—

As empowered people generally do, men value freedom and self-

“In the long years liker must they grow; The man be more of woman, she of man.”

Alfred Lord Tennyson, The Princess, 1847

The gender gap in both social connectedness and power peaks in late adolescence and early adulthood—

So, although women and men are more alike than different, there are some behavior differences between the average woman and man. Are such differences dictated by our biology? Shaped by our cultures and other experiences? Do we vary in the extent to which we are male or female? Read on.

The Nature of Gender: Our Biological Sex

13-

Men and women employ similar solutions when faced with challenges: sweating to cool down, guzzling an energy drink or coffee to get going in the morning, or finding darkness and quiet to sleep. When looking for a mate, men and women also prize many of the same traits. They prefer having a mate who is “kind,” “honest,” and “intelligent.” But according to evolutionary psychologists, in mating-

Biology does not dictate gender, but it can influence it in two ways:

- Genetically—males and females have differing sex chromosomes.

- Physiologically—males and females have differing concentrations of sex hormones, which trigger other anatomical differences.

These two sets of influences began to form you long before you were born, when your tiny body started developing in ways that determined your sex.

Prenatal Sexual DevelopmentSix weeks after you were conceived, you and someone of the other sex looked much the same. Then, as your genes kicked in, your biological sex—

About seven weeks after conception, a single gene on the Y chromosome throws a master switch, which triggers the testes to develop and to produce testosterone, the principal male hormone that promotes development of male sex organs. (Females also have testosterone, but less of it.) The male’s greater testosterone output starts the development of external male sex organs at about the seventh week.

Later, during the fourth and fifth prenatal months, sex hormones bathe the fetal brain and influence its wiring. Different patterns for males and females develop under the influence of the male’s greater testosterone and the female’s ovarian hormones (Hines, 2004; Udry, 2000). Male-

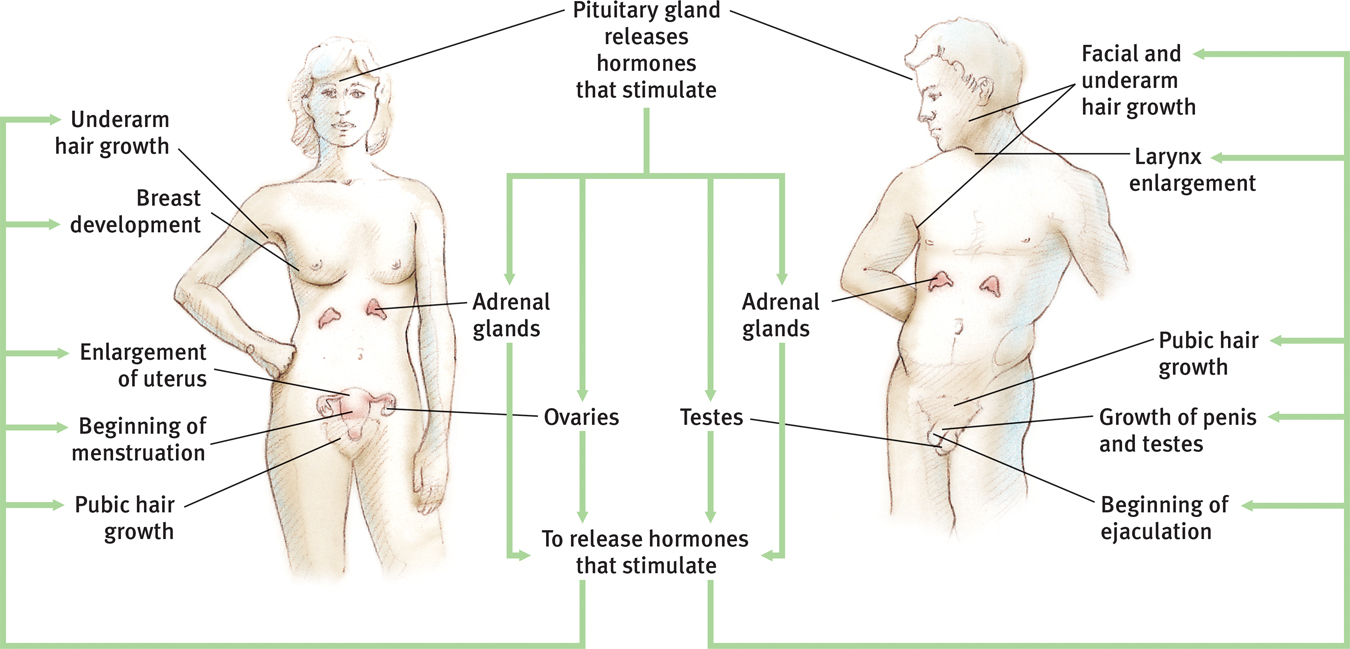

Adolescent Sexual DevelopmentA flood of hormones triggers another period of dramatic physical change during adolescence, when boys and girls enter puberty. In this two-

Girls’ slightly earlier entry into puberty can at first propel them to greater height than boys of the same age (FIGURE 13.5). But boys catch up when they begin puberty, and by age 14, they are usually taller than girls. During these growth spurts, the primary sex characteristics—the reproductive organs and external genitalia—

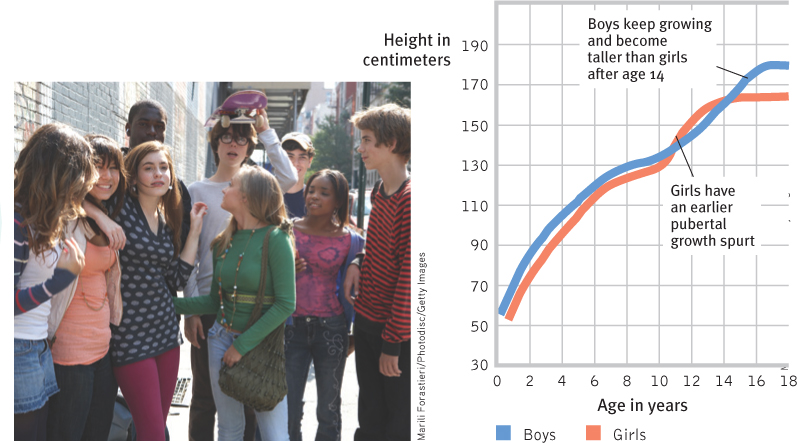

Figure 13.5

Figure 13.5Height differences Throughout childhood, boys and girls are similar in height. At puberty, girls surge ahead briefly, but then boys typically overtake them at about age 14. (Data from Tanner, 1978.) Studies suggest that sexual development and growth spurts are now beginning somewhat earlier than was the case a half-

Figure 13.6

Figure 13.6Body changes at puberty At about age 11 in girls and age 12 in boys, a surge of hormones triggers a variety of visible physical changes.

For boys, puberty’s landmark is the first ejaculation, which often occurs first during sleep (as a “wet dream”). This event, called spermarche (sper-

Pubertal boys may not at first like their sparse beard. (But then it grows on them.)

In girls, the landmark is the first menstrual period (menarche—meh-

Girls prepared for menarche usually experience it positively (Chang et al., 2009). Most women recall their first menstrual period with mixed emotions—

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Adolescence is marked by the onset of ________________ .

puberty

For a 7-minute discussion of our sexual development, visit Launch-Pad’s Video: Gender Development.

For a 7-minute discussion of our sexual development, visit Launch-Pad’s Video: Gender Development.

Sexual Development VariationsSometimes nature blurs the biological line between males and females. When a fetus is exposed to unusual levels of sex hormones, or is especially sensitive to those hormones, the individual may develop a disorder of sexual development, with chromosomes or anatomy not typically male or female. A genetic male may be born with normal male hormones and testes but no penis or a very small one.

In the past,medical professionals often recommended sex reassignment surgery to create an unambiguous identity for some children with this condition. One study reviewed 14 cases of boys who had undergone early surgery and been raised as girls. Of those cases, 6 had later declared themselves male, 5 were living as females, and 3 reported an unclear male or female identity (Reiner & Gearhart, 2004).

Sex-

The bottom line: “Sex matters,” concluded the National Academy of Sciences (2001). Sex-

The Nurture of Gender: Our Culture and Experiences

13-

For many people, biological sex and gender coexist in harmony. Biology draws the outline, and culture paints the details. The physical traits that define us as biological males or females are the same worldwide. But the gender traits that define how men (or boys) and women (or girls) should act, interact, or feel about themselves may differ from one place to another (APA, 2009).

Gender RolesCultures shape our behaviors by defining how we ought to behave in a particular social position, or role. We can see this shaping power in gender roles—the social expectations that guide our behavior as men or as women. Gender roles shift over time. A century ago, North American women could not vote in national elections, serve in the military, or divorce a husband without cause. And if a woman worked for pay outside the home, she would more likely have been a midwife or a seamstress, rather than a surgeon or a fashion designer.

Gender roles can change dramatically in a thin slice of history. At the beginning of the twentieth century, only one country in the world—

Gender roles also vary from one place to another. Nomadic societies of food-

Take a minute to check your own gender expectations. Would you agree that “When jobs are scarce, men should have more rights to a job”? In the United States, Britain, and Spain, barely over 12 percent of adults agree. In Nigeria, Pakistan, and India, about 80 percent of adults agree (Pew, 2010). We’re all human, but my how our views differ. Australia and the Scandinavian countries offer the greatest gender equity, Middle Eastern and North African countries the least (Social Watch, 2006).

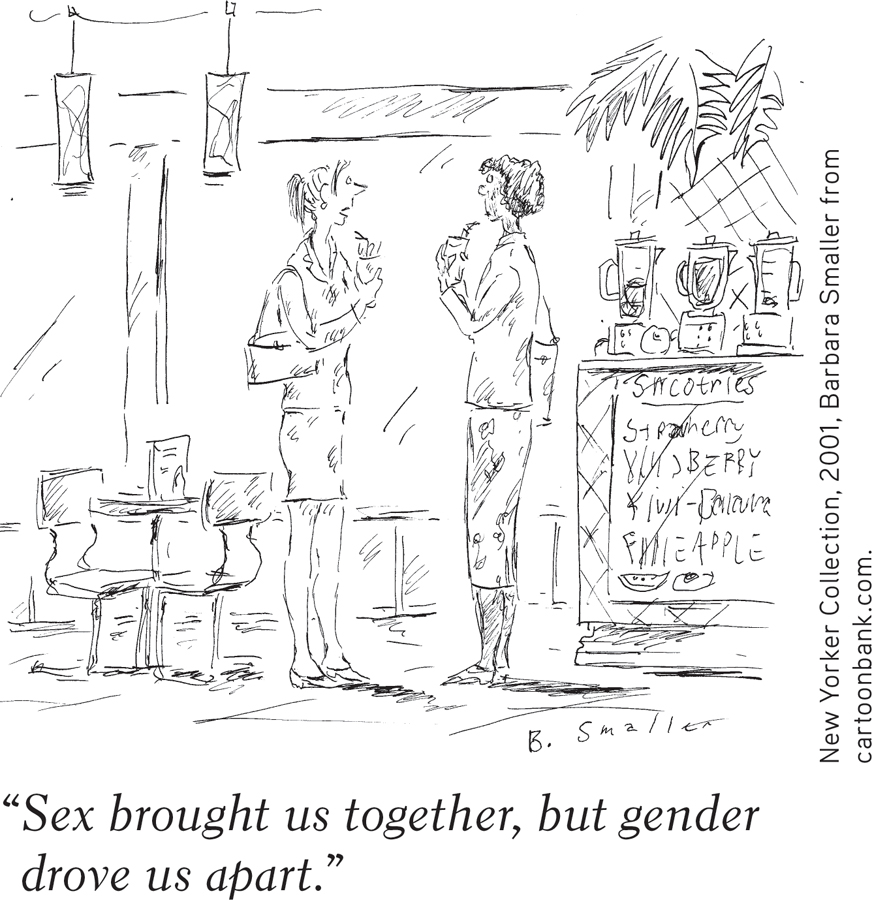

How Do We Learn Gender?A gender role describes how others expect us to think, feel, and act. Our gender identity is our personal sense of being male, female, or a combination of the two. How do we develop that personal viewpoint?

Social learning theory assumes that we acquire our gender identity in childhood, by observing and imitating others’ gender-

Some organize themselves into “boy worlds” and “girl worlds,” each guided by rules. Others seem to prefer androgyny: A blend of male and female roles feels right to them. Androgyny has benefits. Androgynous people are more adaptable. They show greater flexibility in behavior and career choices (Bem, 1993). They tend to be more resilient and self-

How we feel matters, but so does how we think. Early in life, we form schemas, or concepts that help us make sense of our world. Our gender schemas organized our experiences of male-

As a young child, you (like other children) were a “gender detective” (Martin & Ruble, 2004). Before your first birthday, you knew the difference between a male and female voice or face (Martin et al., 2002). After you turned 2, language forced you to label the world in terms of gender. If you are an English speaker, you learned to classify people as he and she. If you are a French speaker, you learned also to classify objects as masculine (“le train”) or feminine (“la table”).

Once children grasp that two sorts of people exist—

For a transgender person, comparing one’s personal gender identity with cultural concepts of gender roles produces feelings of confusion and discord. A transgender person’s gender identity differs from the behaviors or traits considered typical for that person’s birth sex (APA, 2010; Bockting, 2014). A person who was born a female may feel he is a man living in a woman’s body, or a person born male may feel she is a woman living in a man’s body. Some transgender people are also transsexual: They prefer to live as members of the other birth sex. Some transsexual people (about three times as many men as women) may seek medical treatment (including sex-

“The more I was treated as a woman, the more woman I became.”

Writer Jan Morris, male-to-female transsexual

Note that gender identity is distinct from sexual orientation (the direction of one’s sexual attraction). Transgender people may be sexually attracted to people of the opposite birth sex (heterosexual), the same birth sex (homosexual), both sexes (bisexual), or to no one at all (asexual).

Transgender people may express their gender identity by dressing as a person of the other biological sex typically would. Most who dress this way are biological males who are attracted to women (APA, 2010).

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What are gender roles, and what do their variations tell us about our human capacity for learning and adaptation?

Gender roles are social rules or norms for accepted and expected behavior for females and males. The norms associated with various roles, including gender roles, vary widely in different cultural contexts, which is proof that we are very capable of learning and adapting to the social demands of different environments.