14.1 Developmental Psychology's Major Issues

14-1 What three issues have engaged developmental psychologists?

“Nature is all that a man brings with him into the world; nurture is every influence that affects him after his birth.”

Francis Galton, English Men of Science, 1874

DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY EXAMINES OUR PHYSICAL, cognitive, and social development across the life span, with a focus on three major issues:

- Nature and nurture: How does our genetic inheritance (our nature) interact with our experiences (our nurture) to influence our development? (This is our focus in other modules.)

- Continuity and stages: What parts of development are gradual and continuous, like riding an escalator? What parts change abruptly in separate stages, like climbing rungs on a ladder?

- Stability and change: Which of our traits persist through life? How do we change as we age?

Continuity and Stages

Do adults differ from infants as a giant redwood differs from its seedling—a difference created by gradual, cumulative growth? Or do they differ as a butterfly differs from a caterpillar—a difference of distinct stages?

Generally speaking, researchers who emphasize experience and learning see development as a slow, continuous shaping process. Those who emphasize biological maturation tend to see development as a sequence of genetically predisposed stages or steps: Although progress through the various stages may be quick or slow, everyone passes through the stages in the same order.

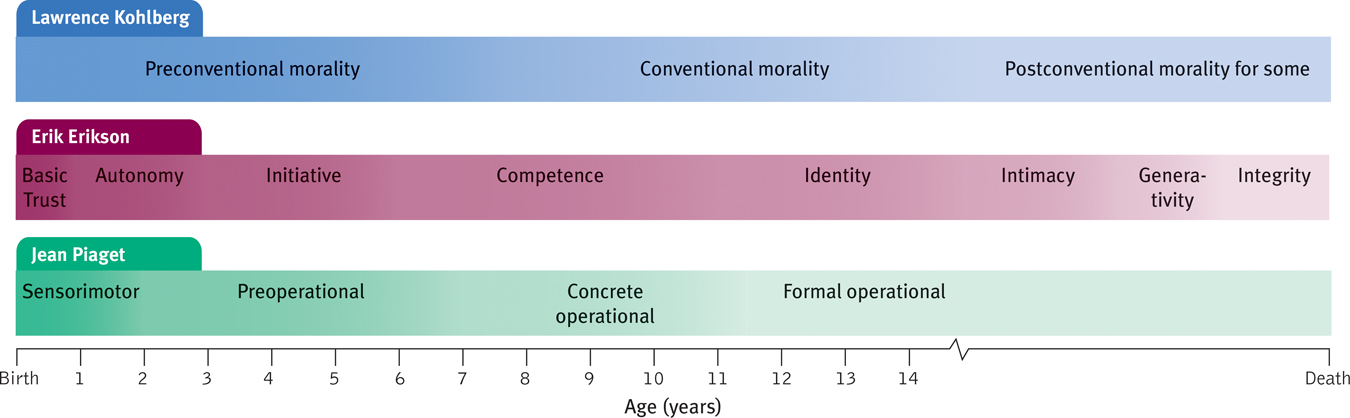

Are there clear-cut stages of psychological development, as there are physical stages such as walking before running? The stage theories we will consider—of Jean Piaget on cognitive development, Lawrence Kohlberg on moral development, and Erik Erikson on psychosocial development—propose developmental stages (summarized in FIGURE 14.1). But as we will also see, some research casts doubt on the idea that life proceeds through neatly defined age-linked stages. Young children have some abilities Piaget attributed to later stages. Kohlberg’s work reflected an individualist worldview and emphasized thinking over acting. And adult life does not progress through a fixed, predictable series of steps. Chance events can influence us in ways we would never have predicted.

Figure 14.1

Figure 14.1Comparing the stage theories (With thanks to Dr. Sandra Gibbs, Muskegon Community College, for inspiring this illustration.)

Nevertheless, the stage concept remains useful. The human brain does experience growth spurts during childhood and puberty that correspond roughly to Piaget’s stages (Thatcher et al., 1987). And stage theories contribute a developmental perspective on the whole life span, by suggesting how people of one age think and act differently when they arrive at a later age.

Stability and Change

As we follow lives through time, do we find more evidence for stability or change? If reunited with a long-lost grade-school friend, do we instantly realize that “it’s the same old Andy”? Or do people we befriend during one period of life seem like strangers at a later period? (At least one acquaintance of mine [DM] would choose the second option. He failed to recognize a former classmate at his 40-year college reunion. The aghast classmate eventually pointed out that she was his long-ago first wife.)

Research reveals that we experience both stability and change. Some of our characteristics, such as temperament, are very stable:

- One research team that studied 1000 people from ages 3 to 38 was struck by the consistency of temperament and emotionality across time (Moffitt et al., 2013; Slutske et al., 2012). Out-of-control 3-year-olds were the most likely to become teen smokers or adult criminals or out-of-control gamblers.

- Other studies have found that hyperactive, inattentive 5-year-olds required more teacher effort at age 12 (Houts et al., 2010); that 6-year-old Canadian boys with conduct problems were four times more likely than other boys to be convicted of a violent crime by age 24 (Hodgins et al., 2013); and that extraversion among British 16-year-olds predicts their future happiness as 60-year-olds (Gale et al., 2013).

- Another research team interviewed adults who, 40 years earlier, had their talkativeness, impulsiveness, and humility rated by their elementary schoolteachers (Nave et al., 2010). To a striking extent, their traits persisted.

“At 70, I would say the advantage is that you take life more calmly. You know that ‘this, too, shall pass’!”

Eleanor Roosevelt, 1954

“As at 7, so at 70,” says a Jewish proverb. The widest smilers in childhood and college photos are, years later, the ones most likely to enjoy enduring marriages (Hertenstein et al., 2009). While 1 in 4 of the weakest college smilers eventually divorced, only 1 in 20 of the widest smilers did so. As people grow older, personality gradually stabilizes (Ferguson, 2010; Hopwood et al., 2011; Kandler et al., 2010). The struggles of the present may be laying a foundation for a happier tomorrow.

We cannot, however, predict all of our eventual traits based on our early years of life (Kagan et al., 1978, 1998). Some traits, such as social attitudes, are much less stable than temperament (Moss & Susman, 1980). Older children and adolescents learn new ways of coping. Although delinquent children have elevated rates of later problems, many confused and troubled children blossom into mature, successful adults (Moffitt et al., 2002; Roberts et al., 2013; Thomas & Chess, 1986). Life is a process of becoming.

In some ways, we all change with age. Most shy, fearful toddlers begin opening up by age 4, and most people become more conscientious, stable, agreeable, and self-confident in the years after adolescence (Lucas & Donnellan, 2009; Roberts & Mroczek, 2008; Shaw et al., 2010). Many irresponsible 18-year-olds have matured into 40-year-old business or cultural leaders. (If you are the former, you aren’t done yet.) Openness, self-esteem, and agreeableness often peak in midlife (Lucas & Donnellan, 2011; Orth et al., 2012; Specht et al., 2011). Such changes can occur without changing a person’s position relative to others of the same age. The hard-driving young adult may mellow by later life, yet still be a relatively driven senior citizen.

Life requires both stability and change. Stability provides our identity. It enables us to depend on others and be concerned about children’s healthy development. Our potential for change gives us our hope for a brighter future. It motivates our concerns about present influences and lets us adapt and grow with experience.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Developmental researchers who emphasize learning and experience are supporting ____________; those who emphasize biological maturation are supporting _________.

continuity; stages

- What findings in psychology support (1) the stage theory of development and (2) the idea of stability in personality across the life span? What findings challenge these ideas?

(1) Stage theory is supported by the work of Piaget (cognitive development), Kohlberg (moral development), and Erikson (psychosocial development), but it is challenged by findings that change is more gradual and less culturally universal than these theorists supposed. (2) Some traits, such as temperament, do exhibit remarkable stability across many years. But we do change in other ways, such as in our social attitudes.