14.2 Prenatal Development and the Newborn

14-2 What is the course of prenatal development, and how do teratogens affect that development?

Please continue to the next section.

Conception

Nothing is more natural than a species reproducing itself. And nothing is more wondrous. For you, the process started inside your grandmother—as an egg formed inside a developing female inside of her. Your mother was born with all the immature eggs she would ever have. Your father, in contrast, began producing sperm cells nonstop at puberty—in the beginning at a rate of more than 1000 sperm during the second it takes to read this phrase.

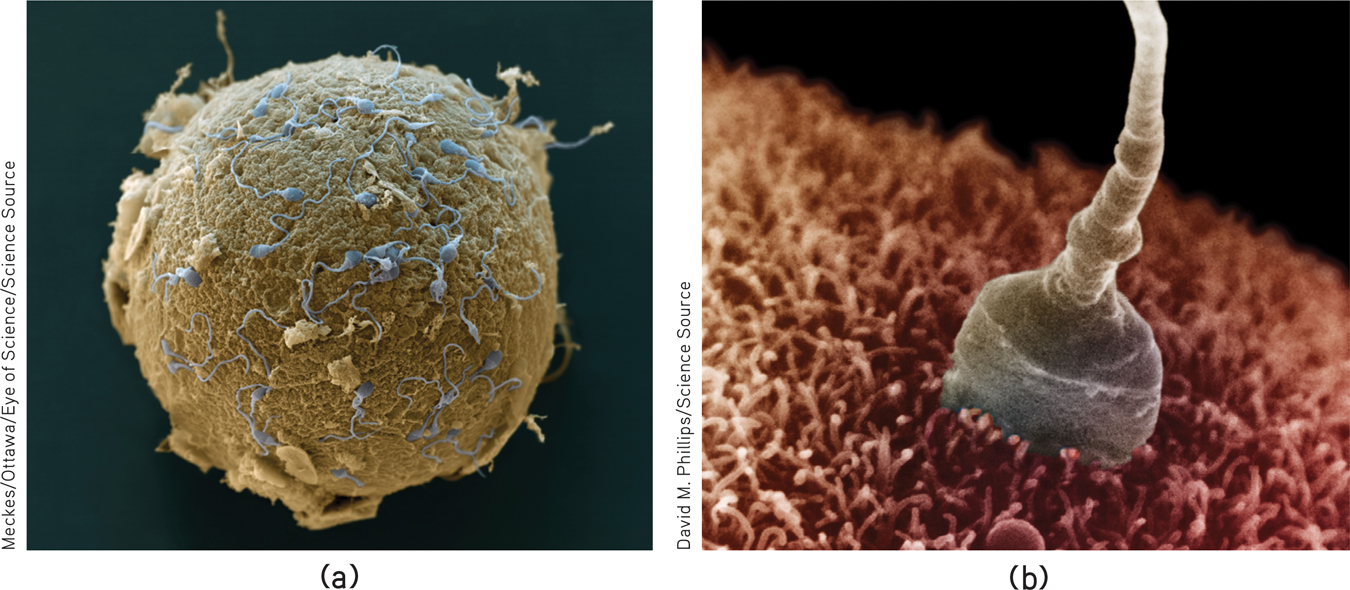

Some time after puberty, your mother’s ovary released a mature egg—a cell roughly the size of the period that ends this sentence. Like space voyagers approaching a huge planet, some 250 million deposited sperm began their race upstream, approaching a cell 85,000 times their own size. Those reaching the egg released digestive enzymes that ate away its protective coating (FIGURE 14.2a). As soon as one sperm penetrated the coating and was welcomed in (Figure 14.2b), the egg’s surface blocked out the others. Before half a day elapsed, the egg nucleus and the sperm nucleus fused: The two became one.

Figure 14.2

Figure 14.2Life is sexually transmitted (a) Sperm cells surround an egg. (b) As one sperm penetrates the egg’s jellylike outer coating, a series of chemical events begins that will cause sperm and egg to fuse into a single cell. If all goes well, that cell will subdivide again and again to emerge 9 months later as a 100-trillion-cell human being.

Consider it your most fortunate of moments. Among 250 million sperm, the one needed to make you, in combination with that one particular egg, won the race. And so it was for innumerable generations before us. If any one of our ancestors had been conceived with a different sperm or egg, or died before conceiving, or not chanced to meet their partner or …. The mind boggles at the improbable, unbroken chain of events that produced us.

Prenatal Development

Fewer than half of all fertilized eggs, called zygotes, survive beyond the first 2 weeks (Grobstein, 1979; Hall, 2004). But for us, good fortune prevailed. One cell became 2, then 4—each just like the first—until this cell division had produced some 100 identical cells within the first week. Then the cells began to differentiate—to specialize in structure and function. How identical cells do this—as if one decides “I’ll become a brain, you become intestines!”—is a puzzle that scientists are just beginning to solve.

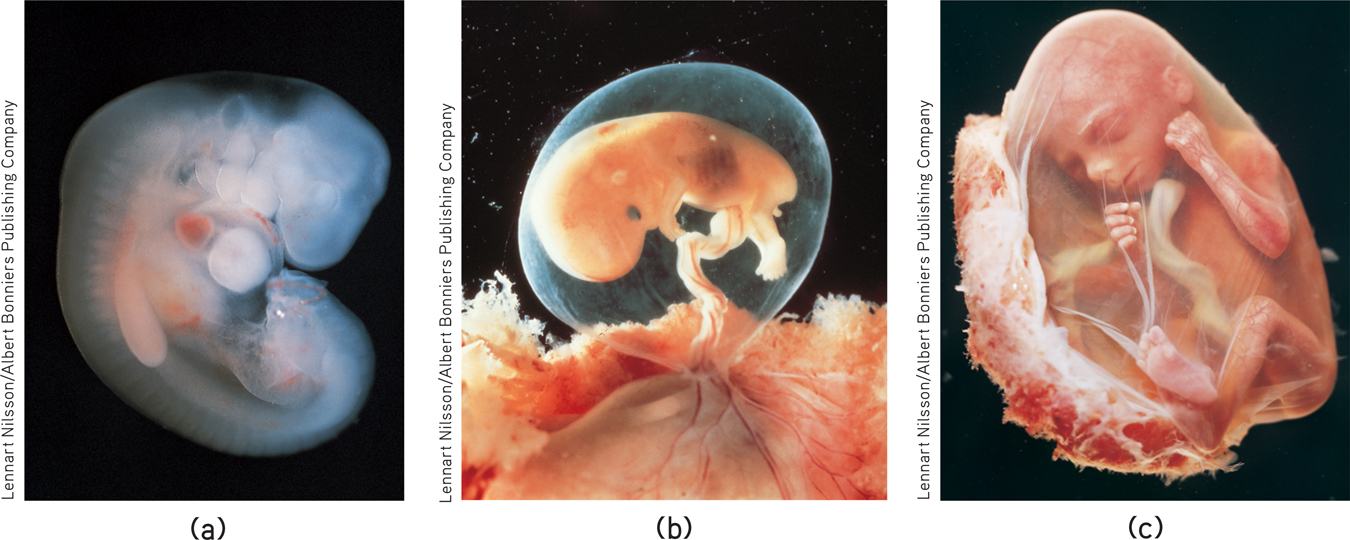

About 10 days after conception, the zygote attaches to the mother’s uterine wall, beginning approximately 37 weeks of the closest human relationship. The zygote’s inner cells become the embryo (FIGURE 14.3a). Many of its outer cells become the placenta, the life-link that transfers nutrients and oxygen from mother to embryo. Over the next 6 weeks, the embryo’s organs begin to form and function. The heart begins to beat.

Figure 14.3

Figure 14.3Prenatal development (a) The embryo grows and develops rapidly. At 40 days, the spine is visible and the arms and legs are beginning to grow. (b) By the end of the second month, when the fetal period begins, facial features, hands, and feet have formed. (c) As the fetus enters the fourth month, its 3 ounces could fit in the palm of your hand.

By 9 weeks after conception, an embryo looks unmistakably human (Figure 14.3b). It is now a fetus (Latin for “offspring” or “young one”). During the sixth month, organs such as the stomach have developed enough to give the fetus a good chance of survival if born prematurely.

At each prenatal stage, genetic and environmental factors affect our development. By the sixth month, microphone readings taken inside the uterus reveal that the fetus is responsive to sound and is exposed to the sound of its mother’s muffled voice (Ecklund-Flores, Hepper, 2005). Immediately after emerging from their underwater world, newborns prefer her voice to another woman’s, or to their father’s (Busnel et al., 1992; DeCasper et al., 1984, 1986, 1994).

They also prefer hearing their mother’s language. At about 30 hours old, American and Swedish newborns pause more in their pacifier sucking when listening to familiar vowels from their mother’s language (Moon et al., 2013). After repeatedly hearing a fake word (tatata) in the womb, Finnish newborns’ brain waves display recognition when hearing the word after birth (Partanen et al., 2013). If their mother spoke two languages during pregnancy, they display interest in both (Byers-Heinlein et al., 2010). And just after birth, babies born to French-speaking mothers tend to cry with the rising intonation of French; babies born to German-speaking mothers cry with the falling tones of German (Mampe et al., 2009). Would you have guessed? The learning of language begins in the womb.

In the two months before birth, fetuses demonstrate learning in other ways, as when they adapt to a vibrating, honking device placed on their mother’s abdomen (Dirix et al., 2009). Like people who adapt to the sound of trains in their neighborhood, fetuses get used to the honking. Moreover, four weeks later, they recall the sound (as evidenced by their blasé response, compared with the reactions of those not previously exposed).

Prenatal development

Zygote: Conception to 2 weeks

Embryo: 2 to 9 weeks

Fetus: 9 weeks to birth

Sounds are not the only stimuli fetuses are exposed to in the womb. In addition to transferring nutrients and oxygen from mother to fetus, the placenta screens out many harmful substances. But some slip by. Teratogens, agents such as viruses and drugs, can damage an embryo or fetus. This is one reason pregnant women are advised not to drink alcoholic beverages. A pregnant woman never drinks alone. As alcohol enters her bloodstream, and her fetus’, it depresses activity in both their central nervous systems. Alcohol use during pregnancy may prime the woman’s offspring to like alcohol and may put them at risk for heavy drinking and alcohol use disorder during their teen years. In experiments, when pregnant rats drank alcohol, their young offspring later displayed a liking for alcohol’s taste and odor (Youngentob et al., 2007, 2009).

“You shall conceive and bear a son. So then drink no wine or strong drink.”

Judges 13:7

Even light drinking or occasional binge drinking can affect the fetal brain (Braun, 1996; Ikonomidou et al., 2000; Sayal et al., 2009). Persistent heavy drinking puts the fetus at risk for birth defects and for future behavior problems, hyperactivity, and lower intelligence. For 1 in about 800 infants, the effects are visible as fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), marked by lifelong physical and mental abnormalities (May & Gossage, 2001). The fetal damage may occur because alcohol has an epigenetic effect: It leaves chemical marks on DNA that switch genes abnormally on or off (Liu et al., 2009).

If a pregnant woman experiences extreme stress, the stress hormones flooding her body may indicate a survival threat to the fetus and produce an earlier delivery (Glynn & Sandman, 2011). Some stress early in life prepares us to cope with later adversity in life. But substantial prenatal stress exposure puts a child at increased risk for health problems such as hypertension, heart disease, obesity, and psychiatric disorders.

For an interactive review of prenatal development, see Launch-Pad’s PsychSim 6: Conception to Birth. LaunchPad also offers the 8-minute Video: Prenatal Development.

For an interactive review of prenatal development, see Launch-Pad’s PsychSim 6: Conception to Birth. LaunchPad also offers the 8-minute Video: Prenatal Development.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- The first two weeks of prenatal development is the period of the _________. The period of the _________ lasts from 9 weeks after conception until birth. The time between those two prenatal periods is considered the period of the _________.

zygote; fetus; embryo

The Competent Newborn

14-3 What are some newborn abilities, and how do researchers explore infants’ mental abilities?

Babies come with software preloaded on their neural hard drives. Having survived prenatal hazards, we as newborns came equipped with automatic reflex responses ideally suited for our survival. We withdrew our limbs to escape pain. If a cloth over our face interfered with our breathing, we turned our head from side to side and swiped at it.

New parents are often in awe of the coordinated sequence of reflexes by which their baby gets food. When something touches their cheek, babies turn toward that touch, open their mouth, and vigorously root for a nipple. Finding one, they automatically close on it and begin sucking—which itself requires a coordinated sequence of reflexive tonguing, swallowing, and breathing. Failing to find satisfaction, the hungry baby may cry—a behavior parents find highly unpleasant and very rewarding to relieve.

“I felt like a man trapped in a woman’s body. Then I was born.”

Comedian Chris Bliss

The pioneering American psychologist William James presumed that the newborn experiences a “blooming, buzzing confusion,” an assumption few people challenged until the 1960s. But then scientists discovered that babies can tell you a lot—if you know how to ask. To ask, you must capitalize on what babies can do—gaze, suck, turn their heads. So, equipped with eye-tracking machines and pacifiers wired to electronic gear, researchers set out to answer parents’ age-old questions: What can my baby see, hear, smell, and think?

Consider how researchers exploit habituation—a decrease in responding with repeated stimulation. We saw this earlier when fetuses adapted to a vibrating, honking device placed on their mother’s abdomen. The novel stimulus gets attention when first presented. With repetition, the response weakens. This seeming boredom with familiar stimuli gives us a way to ask infants what they see and remember.

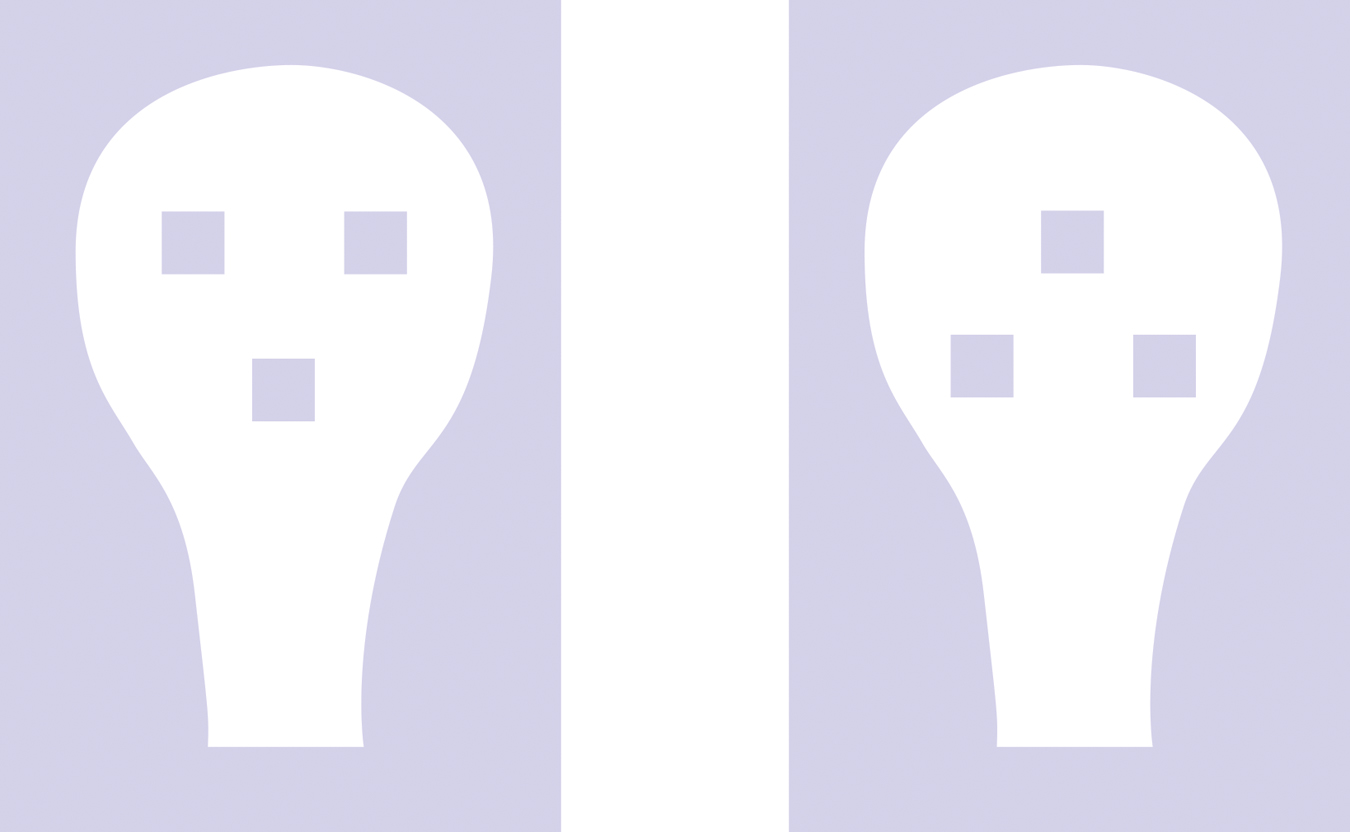

Even as newborns, we prefer sights and sounds that facilitate social responsiveness. We turn our heads in the direction of human voices. We gaze longer at a drawing of a face-like image (FIGURE 14.4). We prefer to look at objects 8 to 12 inches away. Wonder of wonders, that just happens to be the approximate distance between a nursing infant’s eyes and its mother’s (Maurer & Maurer, 1988).

Figure 14.4

Figure 14.4Newborns’ preference for faces When shown these two stimuli with the same elements, Italian newborns spent nearly twice as many seconds looking at the face-like image (Johnson & Morton, 1991). Canadian new-borns—average age 53 minutes in one study—displayed the same apparently inborn preference to look toward faces (Mondloch et al., 1999).

Within days after birth, our brain’s neural networks were stamped with the smell of our mother’s body. Week-old nursing babies, placed between a gauze pad from their mother’s bra and one from another nursing mother, have usually turned toward the smell of their own mother’s pad (MacFarlane, 1978). What’s more, that smell preference lasts. One experiment capitalized on the fact that some nursing mothers in a French maternity ward used a chamomile-scented balm to prevent nipple soreness (Delaunay-El Allam et al., 2010). Twenty-one months later, their toddlers preferred playing with chamomile-scented toys! Their peers who had not sniffed the scent while breast feeding showed no such preference. (This makes one wonder: Will adults, who as babies associated chamomile scent with their mother’s breast, become devoted chamomile tea drinkers?) Such studies reveal the remarkable abilities we come with as we enter our world.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Developmental psychologists use repeated stimulation to test an infant’s ____________ to a stimulus.

habituation