15.1 Physical Development

15-1 During infancy and childhood, how do the brain and motor skills develop?

Please continue to the next section.

Brain Development

In your mother’s womb, your developing brain formed nerve cells at the explosive rate of nearly one-quarter million per minute. The developing brain cortex actually overproduces neurons, with the number peaking at 28 weeks (Rabinowicz et al., 1996, 1999).

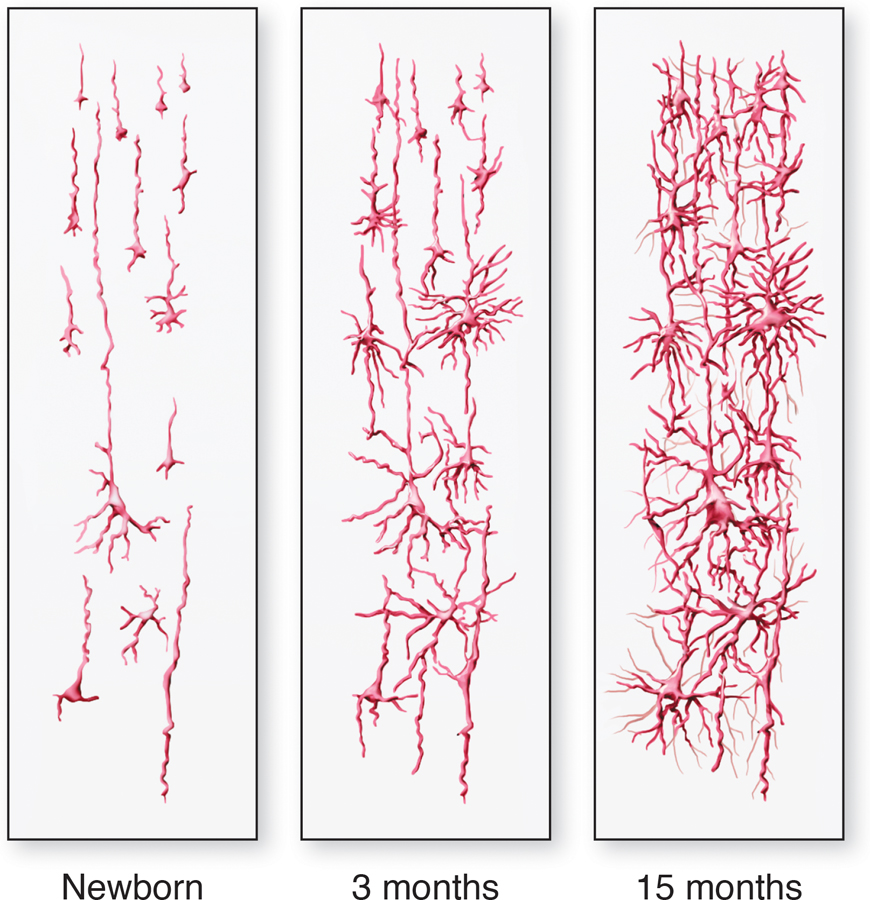

From infancy on, brain and mind—neural hardware and cognitive software—develop together. On the day you were born, you had most of the brain cells you would ever have. However, your nervous system was immature: After birth, the branching neural networks that eventually enabled you to walk, talk, and remember had a wild growth spurt (FIGURE 15.1). From ages 3 to 6, the most rapid growth was in your frontal lobes, which enable rational planning. This explains why preschoolers display a rapidly developing ability to control their attention and behavior (Garon et al., 2008).

Figure 15.1

Figure 15.1Drawings of human cerebral cortex sections In humans, the brain is immature at birth. As the child matures, the neural networks grow increasingly more complex.

The brain’s association areas—those linked with thinking, memory, and language—are the last cortical areas to develop. As they do, mental abilities surge (Chugani & Phelps, 1986; Thatcher et al., 1987). Fiber pathways supporting agility, language, and self-control proliferate into puberty. Under the influence of adrenal hormones, tens of billions of synapses form and organize, while a use-it-or-lose-it pruning process shuts down unused links (Paus et al., 1999; Thompson et al., 2000).

Motor Development

The developing brain enables physical coordination. As an infant exercises its maturing muscles and nervous system, skills emerge. With occasional exceptions, the sequence of physical (motor) development is universal. Babies roll over before they sit unsupported, and they usually crawl on all fours before they walk. These behaviors reflect not imitation but a maturing nervous system; blind children, too, crawl before they walk.

And how do infants learn to walk? With a great deal of practice. Karen Adolph and her colleagues (2012, 2014) documented that effort by observing 20 experienced crawlers and 20 novice walkers—all 12 months of age. In an average hour, the novice walkers fell 32 times. Still, walking beats crawling for getting someplace: Walkers took about 1500 steps per hour. They traveled three times the distance as crawlers. And they saw the whole room (unlike crawlers, who looked mostly at the floor).

In the United States, 25 percent of all babies walk by 11 months of age, 50 percent within a week after their first birthday, and 90 percent by age 15 months (Frankenburg et al., 1992). The recommended infant back to sleep position (putting babies to sleep on their backs to reduce the risk of a smothering crib death) has been associated with somewhat later crawling but not with later walking (Davis et al., 1998; Lipsitt, 2003).

In the eight years following the 1994 launch of a U.S. Back to Sleep educational campaign, the number of infants sleeping on their stomach dropped from 70 to 11 percent—and sudden unexpected infant deaths fell significantly (Braiker, 2005).

Genes guide motor development. Identical twins typically begin walking on nearly the same day (Wilson, 1979). Maturation—including the rapid development of the cerebellum at the back of the brain—creates our readiness to learn walking at about age 1. The same is true for other physical skills, including bowel and bladder control. Before necessary muscular and neural maturation, neither pleading nor punishment will produce successful toilet training.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- The biological growth process, called _________, explains why most children begin walking by about 12 to 15 months.

maturation

Brain Maturation and Infant Memory

Can you recall your first day of preschool or your third birthday party? In one study, three-year-olds displayed recognition of someone they met at age one (Kingo et al., 2014). But our earliest conscious memories seldom predate our third birthday. We see this infantile amnesia in the memories of some preschoolers who experienced an emergency fire evacuation caused by a burning popcorn maker. Seven years later, they were able to recall the alarm and what caused it—if they were 4 to 5 years old at the time. Those experiencing the event as 3-year-olds could not remember the cause and usually misrecalled being already outside when the alarm sounded (Pillemer, 1995). Other studies have confirmed that our average age of earliest conscious memory is 3.5 years (Bauer, 2002, 2007). But as children mature, by age 7 or so, childhood amnesia wanes, and they become increasingly capable of remembering experiences, even for a year or more (Bauer & Larkina, 2013; Morris et al., 2010). The brain areas underlying memory, such as the hippocampus and frontal lobes, continue to mature into adolescence (Bauer, 2007).

Apart from constructed memories based on photos and family stories, we consciously recall little from our early years, yet our brain was processing and storing information. While finishing her doctoral work in psychology, Carolyn Rovee-Collier observed nonverbal infant memory in action. Her colicky 2-month-old, Benjamin, could be calmed by moving a crib mobile. Weary of hitting the mobile, she strung a cloth ribbon connecting the mobile to Benjamin’s foot. Soon, he was kicking his foot to move the mobile. Thinking about her unintended home experiment, Rovee-Collier realized that, contrary to popular opinion in the 1960s, babies are capable of learning. To know for sure that her son wasn’t just a whiz kid, she repeated the experiment with other infants (Rovee-Collier, 1989, 1999). Sure enough, they, too, soon kicked more when hitched to a mobile, both on the day of the experiment and the day after. If, however, she hitched them to a different mobile the next day, the infants showed no learning, indicating that they remembered the original mobile and recognized the difference. Moreover, when tethered to the familiar mobile a month later, they remembered the association and again began kicking (FIGURE 15.2).

Figure 15.2

Figure 15.2Infant at work Babies only 3 months old can learn that kicking moves a mobile, and they can retain that learning for a month. (From Rovee-Collier, 1989, 1997.)

Traces of forgotten childhood languages may also persist. One study tested English-speaking British adults who had no conscious memory of the Hindi or Zulu they had spoken as children. Yet, up to age 40, they could relearn subtle sound contrasts in these languages that other people could not learn (Bowers et al., 2009). What the conscious mind does not know and cannot express in words, the nervous system and our two-track mind somehow remember.