15.3 Social Development

15-4 How do parent-infant attachment bonds form?

From birth, babies are social creatures, developing an intense bond with their caregivers. Infants come to prefer familiar faces and voices, then to coo and gurgle when given a parent’s attention. After about 8 months, soon after object permanence emerges and children become mobile, a curious thing happens: They develop stranger anxiety. They may greet strangers by crying and reaching for familiar caregivers. “No! Don’t leave me!” their distress seems to say. Children this age have schemas for familiar faces; when they cannot assimilate the new face into these remembered schemas, they become distressed (Kagan, 1984). Once again, we see an important principle: The brain, mind, and social-emotional behavior develop together.

Human Bonding

One-year-olds typically cling tightly to a parent when they are frightened or expect separation. Reunited after being apart, they shower the parent with smiles and hugs. This attachment bond is a powerful survival impulse that keeps infants close to their caregivers. Infants become attached to those—typically their parents—who are comfortable and familiar. For many years, psychologists reasoned that infants became attached to those who satisfied their need for nourishment. But an accidental finding overturned this explanation.

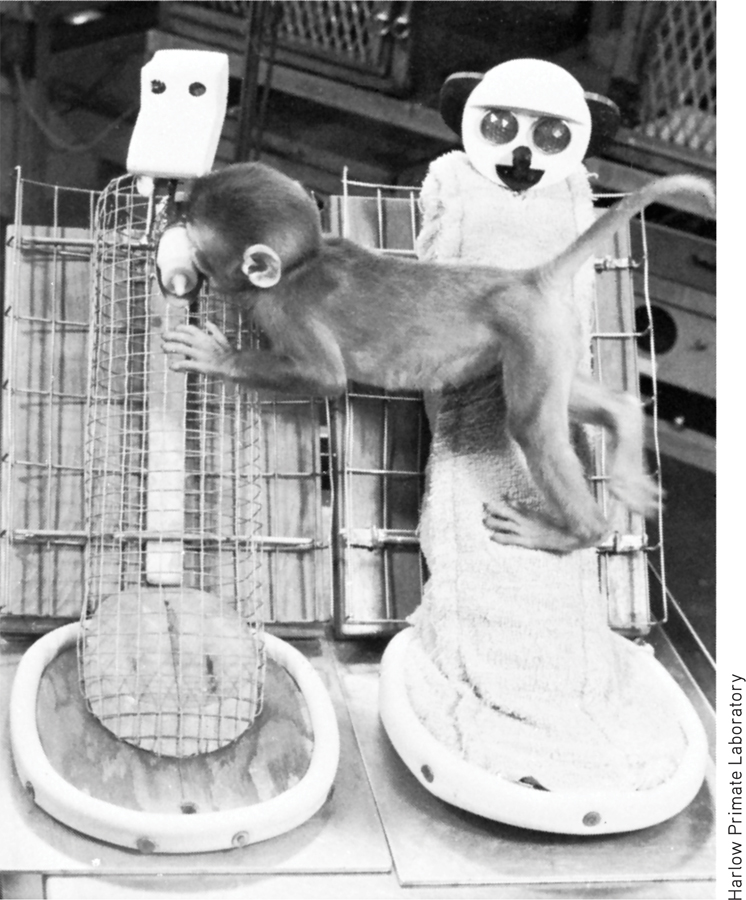

Body ContactDuring the 1950s, University of Wisconsin psychologists Harry Harlow and Margaret Harlow bred monkeys for their learning studies. To equalize experiences and to isolate any disease, they separated the infant monkeys from their mothers shortly after birth and raised them in sanitary individual cages, which included a cheesecloth baby blanket (Harlow et al., 1971). Then came a surprise: When their soft blankets were taken to be laundered, the monkeys became distressed.

The Harlows recognized that this intense attachment to the blanket contradicted the idea that attachment derives from an association with nourishment. But how could they show this more convincingly? To pit the drawing power of a food source against the contact comfort of the blanket, they created two artificial mothers. One was a bare wire cylinder with a wooden head and an attached feeding bottle, the other a cylinder wrapped with terry cloth.

For some people a perceived relationship with God functions as do other attachments, by providing a secure base for exploration and a safe haven when threatened (Granqvist et al., 2010; Kirkpatrick, 1999).

When raised with both, the monkeys overwhelmingly preferred the comfy cloth mother (FIGURE 15.11 ). Like other infants clinging to their live mothers, the monkey babies would cling to their cloth mothers when anxious. When exploring their environment, they used her as a secure base, as if attached to her by an invisible elastic band that stretched only so far before pulling them back. Researchers soon learned that other qualities—rocking, warmth, and feeding—made the cloth mother even more appealing.

Figure 15.11

Figure 15.11The Harlows’ monkey mothers Psychologists Harry Harlow and Margaret Harlow raised monkeys with two artificial mothers—one a bare wire cylinder with a wooden head and an attached feeding bottle, the other a cylinder with no bottle but covered with foam rubber and wrapped with terry cloth. The Harlows’ discovery surprised many psychologists: The infants much preferred contact with the comfortable cloth mother, even while feeding from the nourishing mother.

Human infants, too, become attached to parents who are soft and warm and who rock, feed, and pat. Much parent-infant emotional communication occurs via soothing or arousing touch (Hertenstein et al., 2006). Human attachment also consists of one person providing another with a secure base from which to explore and a safe haven when distressed. As we mature, our secure base and safe haven shift—from parents to peers and partners (Cassidy & Shaver, 1999). But at all ages we are social creatures. We gain strength when someone offers, by words and actions, a safe haven: “I will be here. I am interested in you. Come what may, I will support you” (Crowell & Waters, 1994).

FamiliarityContact is one key to attachment. Another is familiarity. In many animals, attachments based on familiarity form during a critical period—an optimal period when certain events must take place to facilitate proper development (Bornstein, 1989). For goslings, ducklings, or chicks, that period falls in the hours shortly after hatching, when the first moving object they see is normally their mother. From then on, the young fowl follow her, and her alone.

Konrad Lorenz (1937) explored this rigid attachment process, called imprinting. He wondered: What would ducklings do if he was the first moving creature they observed? What they did was follow him around: Everywhere that Konrad went, the ducks were sure to go. Although baby birds imprint best to their own species, they also will imprint to a variety of moving objects—an animal of another species, a box on wheels, a bouncing ball (Colombo, 1982; Johnson, 1992). Once formed, this attachment is difficult to reverse.

Children—unlike ducklings—do not imprint. However, they do become attached to what they’ve known. Mere exposure to people and things fosters fondness. Children like to reread the same books, rewatch the same movies, reenact family traditions. They prefer to eat familiar foods, live in the same familiar neighborhood, attend school with the same old friends. Familiarity is a safety signal. Familiarity breeds content.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What distinguishes imprinting from attachment?

Attachment is the normal process by which we form emotional ties with important others. Imprinting occurs only in certain animals that have a critical period very early in their development during which they must form their attachments, and they do so in an inflexible manner.

Attachment Differences

15-5 How have psychologists studied attachment differences, and what have they learned?

What accounts for children’s attachment differences? To answer this question, Mary Ainsworth (1979) designed the strange situation experiment. She observed mother– infant pairs at home during their first six months. Later she observed the 1-year-old infants in a strange situation (usually a laboratory playroom). Such research has shown that about 60 percent of infants display secure attachment. In their mother’s presence they play comfortably, happily exploring their new environment. When she leaves, they become distressed; when she returns, they seek contact with her.

Other infants avoid attachment or show insecure attachment, marked either by anxiety or avoidance of trusting relationships. They are less likely to explore their surroundings; they may even cling to their mother. When she leaves, they either cry loudly and remain upset or seem indifferent to her departure and return (Ainsworth, 1973, 1989; Kagan, 1995; van IJzendoorn & Kroonenberg, 1988).

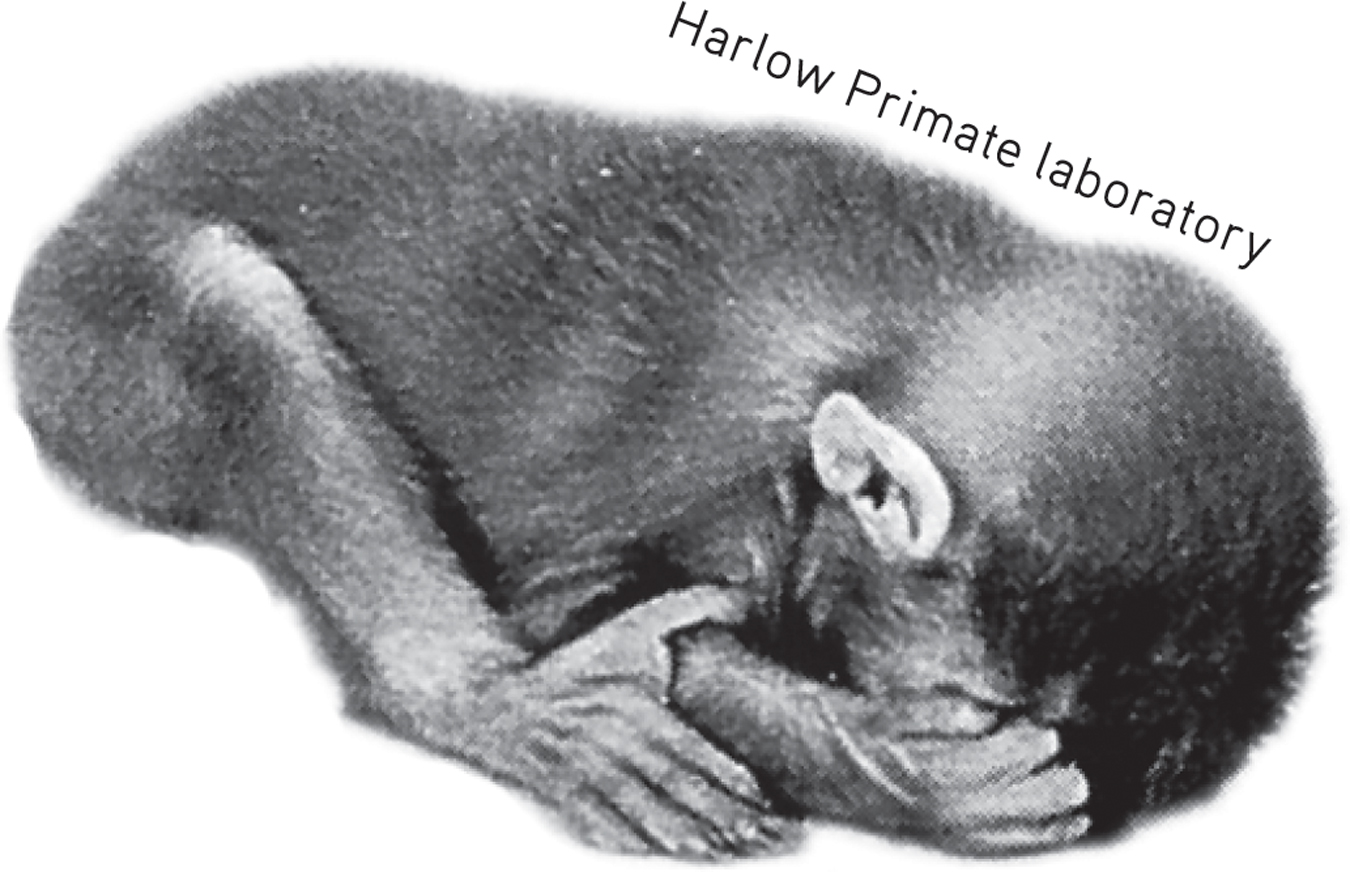

Ainsworth and others found that sensitive, responsive mothers—those who noticed what their babies were doing and responded appropriately—had infants who exhibited secure attachment (De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, 1997). Insensitive, unresponsive mothers—mothers who attended to their babies when they felt like doing so but ignored them at other times—often had infants who were insecurely attached. The Harlows’ monkey studies, with unresponsive artificial mothers, produced even more striking effects. When put in strange situations without their artificial mothers, the deprived infants were terrified (FIGURE 15.12).

Figure 15.12

Figure 15.12Social deprivation and fear In the Harlows’ experiments, monkeys raised with inanimate surrogate mothers were overwhelmed when placed in strange situations without that source of emotional security. (Today there is greater oversight and concern for animal welfare, which would regulate this type of study.)

Although remembered by some as the researcher who tortured helpless monkeys, Harry Harlow defended his methods: “Remember, for every mistreated monkey there exist a million mistreated children,” he said, expressing the hope that his research would sensitize people to child abuse and neglect. “No one who knows Harry’s work could ever argue that babies do fine without companionship, that a caring mother doesn’t matter,” noted Harlow biographer Deborah Blum (2010, pp. 292, 307). “And since we … didn’t fully believe that before Harry Harlow came along, then perhaps we needed—just once—to be smacked really hard with that truth so that we could never again doubt.”

“Harry Harlow, whose name has become synonymous with cruel monkey experiments, actually helped put an end to cruel child-rearing practices.”

Primatologist Frans de Waal (2011)

So, caring parents matter. But is attachment style the result of parenting? Or is attachment style the result of genetically influenced temperament—a person’s characteristic emotional reactivity and intensity? Twin and developmental studies reveal that heredity matters, too (Picardi et al., 2011; Raby et al., 2012). Shortly after birth, some babies are noticeably difficult—irritable, intense, and unpredictable. Others are easy—cheerful, relaxed, and feeding and sleeping on predictable schedules (Chess & Thomas, 1987). By neglecting such inborn differences, the parenting studies, noted Judith Harris (1998), are like “comparing foxhounds reared in kennels with poodles reared in apartments.” So to separate nature and nurture, we would need to vary parenting while controlling temperament. (Pause and think: If you were the researcher, how might you have done this?)

Dutch researcher Dymphna van den Boom’s solution was to randomly assign 100 temperamentally difficult 6-to 9-month-olds to either an experimental group, in which mothers received personal training in sensitive responding, or to a control group, in which they did not. At 12 months of age, 68 percent of the infants in the experimental group were rated securely attached, as were only 28 percent of the control group infants. Other studies have confirmed that intervention programs can increase parental sensitivity and, to a lesser extent, infant attachment security (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2003; Van Zeijl et al., 2006).

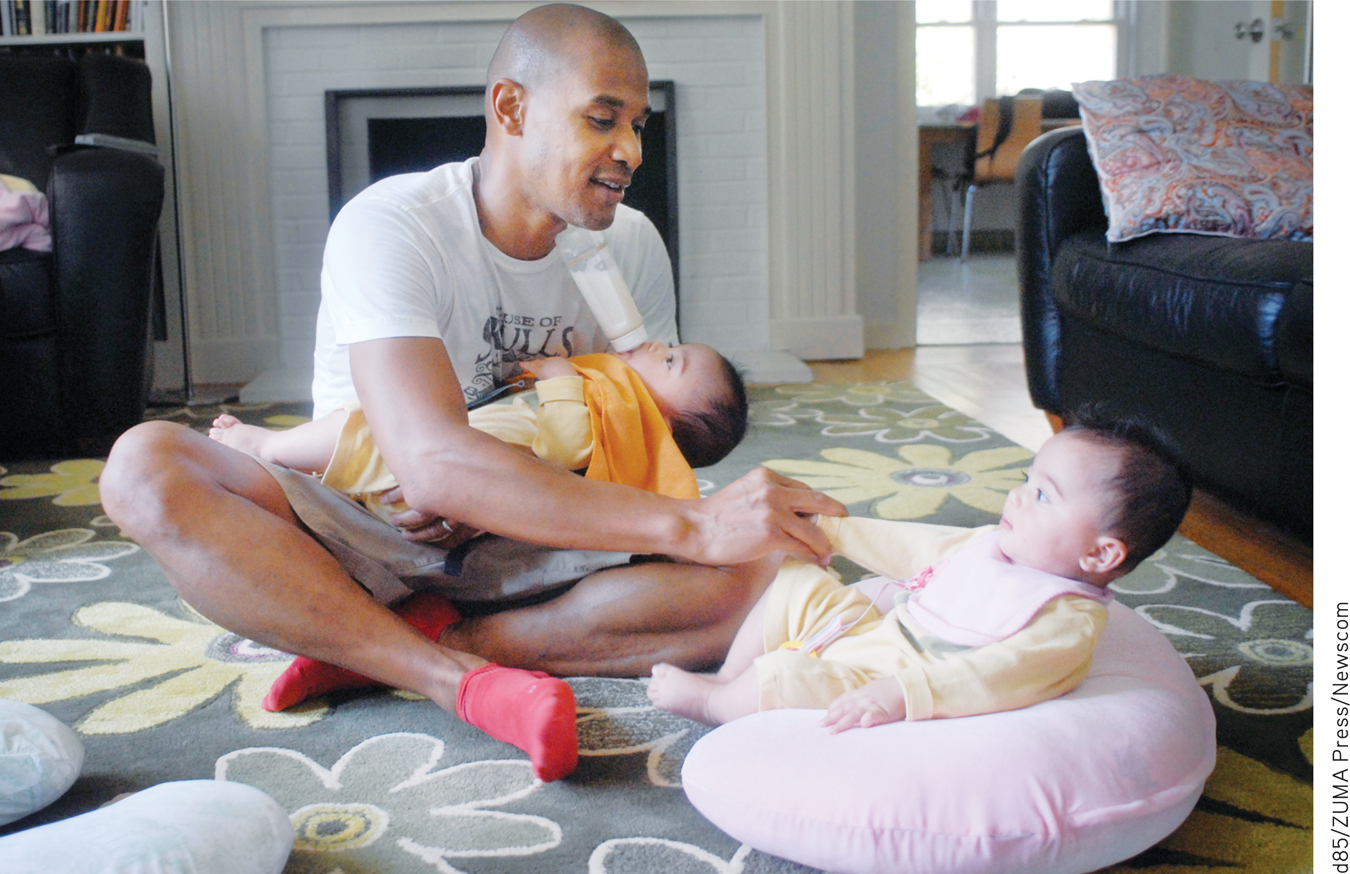

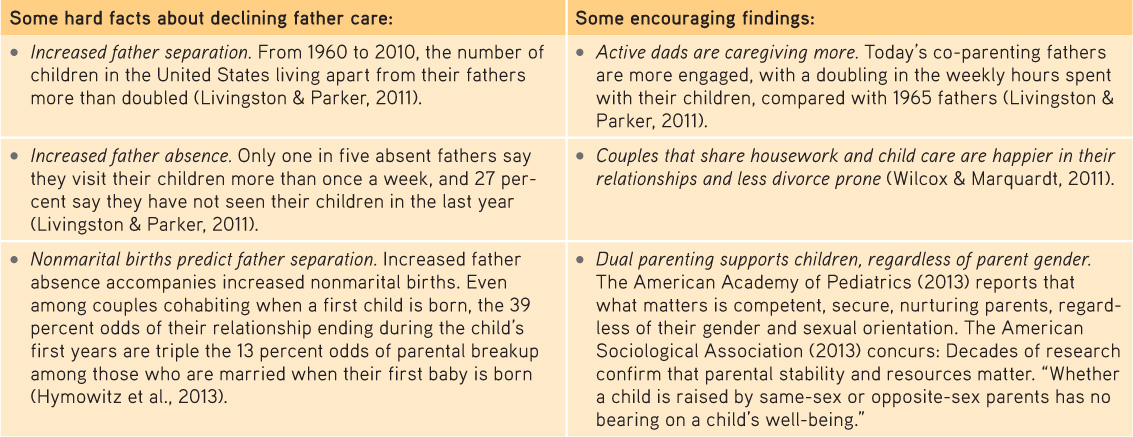

As these examples indicate, researchers have more often studied mother care than father care. Infants who lack a caring mother are said to suffer “maternal deprivation”; those lacking a father’s care merely experience “father absence.” This reflects a wider attitude in which “fathering a child” has meant impregnating, and “mothering” has meant nurturing. But fathers are more than just mobile sperm banks. Across nearly 100 studies worldwide, a father’s love and acceptance have been comparable to a mother’s love in predicting their offspring’s health and well-being (Rohner & Veneziano, 2001; see also TABLE 15.2). In one mammoth British study following 7259 children from birth to adulthood, those whose fathers were most involved in parenting (through outings, reading to them, and taking an interest in their education) tended to achieve more in school, even after controlling for other factors such as parental education and family wealth (Flouri & Buchanan, 2004).

Table 15.2

Table 15.2Dual Parenting Facts

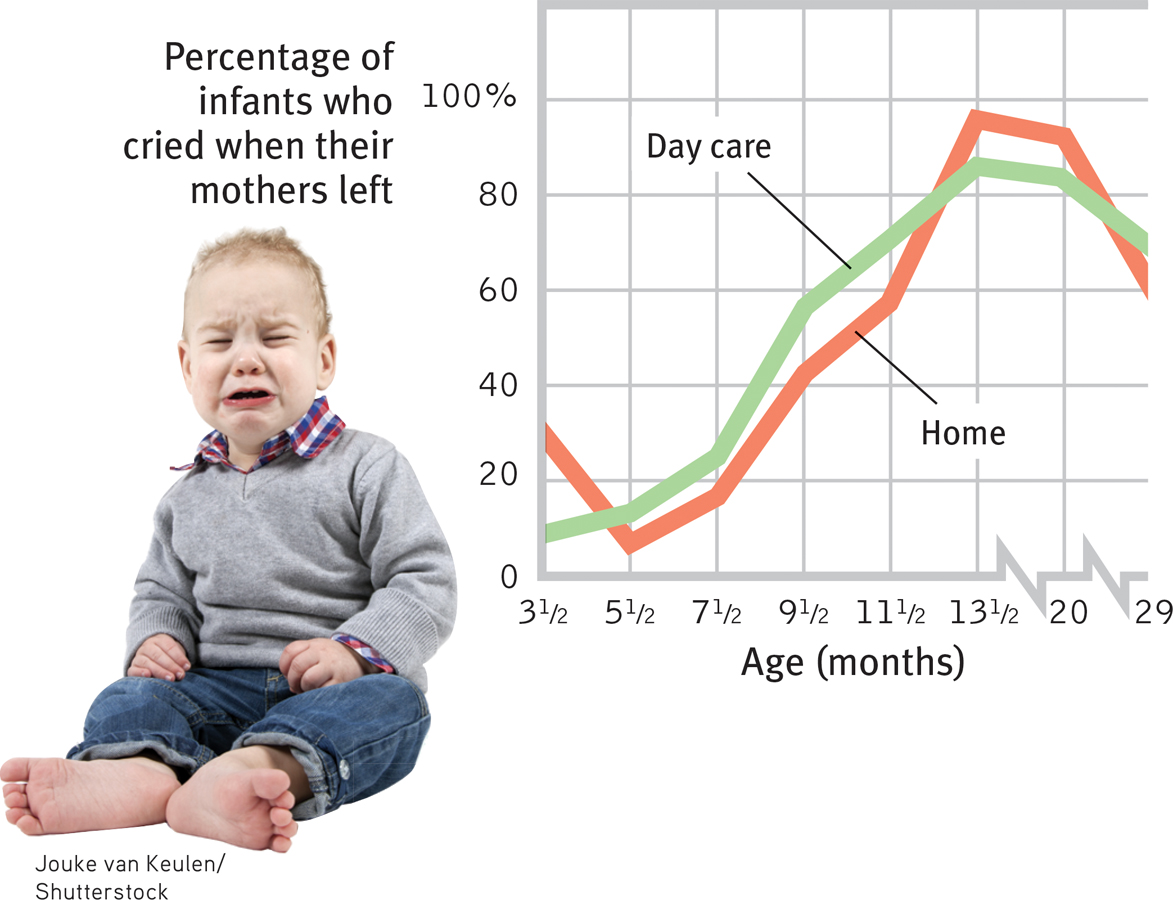

Children’s anxiety over separation from parents peaks at around 13 months, then gradually declines (FIGURE 15.13). This happens whether they live with one parent or two, are cared for at home or in a day-care center, live in North America, Guatemala, or the Kalahari Desert. Does this mean our need for and love of others also fades away? Hardly. Our capacity for love grows, and our pleasure in touching and holding those we love never ceases.

Figure 15.13

Figure 15.13Infants’ distress over separation from parents In an experiment, groups of infants were left by their mothers in an unfamiliar room. In both groups, the percentage who cried when the mother left peaked at about 13 months. Whether the infant had experienced day care made little difference. (From Kagan, 1976.)

Attachment Styles and Later RelationshipsDevelopmental theorist Erik Erikson (1902–1994), working with his wife, Joan Erikson (1902–1997), believed that securely attached children approach life with a sense of basic trust—a sense that the world is predictable and reliable. He attributed basic trust not to environment or inborn temperament, but to early parenting. He theorized that infants blessed with sensitive, loving caregivers form a lifelong attitude of trust rather than fear.

Many researchers now believe that our early attachments form the foundation for our adult relationships and our comfort with affection and intimacy (Birnbaum et al., 2006; Fraley et al., 2013). People who report secure relationships with their parents tend to enjoy secure friendships (Gorrese & Ruggieri, 2012). When leaving home to attend college—another kind of “strange situation”—those closely attached to parents tend to adjust well (Mattanah et al., 2011).

“Out of the conflict between trust and mistrust, the infant develops hope, which is the earliest form of what gradually becomes faith in adults.”

Erik Erikson (1983)

Our adult styles of romantic love tend to exhibit (1) secure, trusting attachment; (2) insecure, anxious attachment; or (3) the avoidance of attachment (Feeney & Noller, 1990; Rholes & Simpson, 2004; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2007). Feeling insecurely attached to others may take either of these two main forms (Fraley et al., 2011). In the one, anxiety, people constantly crave acceptance but remain vigilant to signs of possible rejection. (Being sensitive to threat, anxiously attached people also tend to be skilled lie detectors and poker players [Ein-Dor & Perry, 2012, 2013].) In the other, avoidance, people experience discomfort getting close to others and use avoidant strategies to maintain distance from others. In romantic relationships, an anxious attachment style diminishes social connections and support. An avoidant style decreases commitment, increases openness to infidelity, and increases conflict (DeWall et al., 2011; Li & Chan, 2012).

Adult attachment styles can also affect relationships with one’s own children. But say this for those (nearly half of all humans) who exhibit insecure attachments: Anxious or avoidant tendencies have helped our groups detect or escape dangers (Ein-Dor et al, 2010).

Deprivation of Attachment

15-6 How does childhood neglect or abuse affect children’s attachments?

If secure attachment nurtures social competence, what happens when circumstances prevent a child’s forming attachments? In all of psychology, there is no sadder research literature. Babies locked away at home under conditions of abuse or extreme neglect are often withdrawn, frightened, even speechless. The same is true of those raised in institutions without the stimulation and attention of a regular caregiver, as was tragically illustrated during the 1970s and 1980s in Romania. Having decided that economic growth for his impoverished country required more human capital, Nicolae Ceaus¸escu, Romania’s Communist dictator, outlawed contraception, forbade abortion, and taxed families with fewer than five children. The birthrate skyrocketed. But unable to afford the children they had been coerced into having, many families abandoned them to government-run orphanages with untrained and overworked staff. Child-to-caregiver ratios often were 15 to 1, so the children were deprived of healthy attachments with at least one adult. When tested after Ceauşescu was assassinated in 1989, these children had lower intelligence scores and double the 20 percent rate of anxiety symptoms found in children assigned to quality foster care settings (Nelson et al., 2009, 2014). Dozens of other studies across 19 countries have confirmed that orphaned children tend to fare better on later intelligence tests if raised in family homes. This is especially so for those placed at an early age (van IJzendoorn et al., 2008).

“What is learned in the cradle, lasts to the grave.”

French proverb

Most children growing up under adversity (as did the surviving children of the Holocaust) are resilient; they withstand the trauma and become normal adults (Helmreich, 1992; Masten, 2001). So do most victims of childhood sexual abuse, noted Harvard researcher Susan Clancy (2010), while emphasizing that using children for sex is revolting and never the victim’s fault. Indeed, hardship short of trauma often boosts mental toughness (Seery, 2011). And though growing up poor puts children at risk for some social pathologies, growing up rich puts them at risk for other pathologies. Affluent children are at elevated risk for substance abuse, eating disorders, anxiety, and depression (Lund & Dearing, 2012; Luthar et al., 2013). So when you face adversity, consider the possible silver lining.

But those who experience no sharp break from their abusive past don’t bounce back so readily. The Harlows’ monkeys raised in total isolation, without even an artificial mother, bore lifelong scars. As adults, when placed with other monkeys their age, they either cowered in fright or lashed out in aggression. When they reached sexual maturity, most were incapable of mating. If artificially impregnated, females often were neglectful, abusive, even murderous toward their first-born. Another primate experiment confirmed the abuse-breeds-abuse phenomenon: 9 of 16 female monkeys who had been abused by their mothers became abusive parents, as did no female raised by a nonabusive mother (Maestripieri, 2005).

In humans, too, the unloved may become the unloving. Most abusive parents—and many condemned murderers—have reported being neglected or battered as children (Kempe & Kempe, 1978; Lewis et al., 1988). Some 30 percent of people who have been abused later abuse their children—a rate lower than that found in the primate study, but four times the U.S. national rate of child abuse (Dumont et al., 2007; Kaufman & Zigler, 1987).

Although most abused children do not later become violent criminals or abusive parents, extreme early trauma may nevertheless leave footprints on the brain. Like battle-stressed soldiers, their brains respond to angry faces with heightened activity in threat-detecting areas (McCrory et al., 2011). In conflict-plagued homes, even sleeping infants’ brains show heightened reactivity to hearing angry speech (Graham et al., 2013). As adults, they exhibit stronger startle responses (Jovanovic et al., 2009). If repeatedly threatened and attacked while young, normally placid golden hamsters grow up to be cowards when caged with same-sized hamsters, or bullies when caged with weaker ones (Ferris, 1996). Such animals show changes in the brain chemical serotonin, which calms aggressive impulses. A similarly sluggish serotonin response has been found in abused children who become aggressive teens and adults. By sensitizing the stress response system, early stress can permanently heighten reactions to later stress (van Zuiden et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2012). In another module, we note that child abuse also leaves epigenetic marks—chemical tags—that can alter normal gene expression.

“Stress can set off a ripple of hormonal changes that permanently wire a child’s brain to cope with a malevolent world.”

Abuse researcher Martin Teicher (2002)

Such findings help explain why young children who have survived severe or prolonged physical abuse, childhood sexual abuse, bullying, or wartime atrocities are at increased risk for health problems, psychological disorders, substance abuse, and criminality (Nanni et al., 2012; Trickett et al., 2011; Wolke et al., 2013; Whitelock et al., 2013). In one national study of 43,093 adults, 8 percent reported experiencing physical abuse at least fairly often before age 18 (Sugaya et al., 2012). Among these, 84 percent had experienced at least one psychiatric disorder. Moreover, the greater the abuse, the greater the odds of anxiety, depression, and substance use disorder, and of attempted suicide. Abuse victims are at considerable risk for depression if they carry a gene variation that spurs stress-hormone production (Bradley et al., 2008). As we will see again and again, behavior and emotion arise from a particular environment interacting with particular genes.

We adults also suffer when our attachment bonds are severed. Whether through death or separation, a break produces a predictable sequence. Agitated preoccupation with the lost partner is followed by deep sadness and, eventually, the beginnings of emotional detachment and a return to normal living (Hazan & Shaver, 1994). Newly separated couples who have long ago ceased feeling affection are sometimes surprised at their desire to be near the former partner. Detaching is a process, not an event.

Self-Concept

15-7 How do children’s self-concepts develop?

Infancy’s major social achievement is attachment. Childhood’s major social achievement is a positive sense of self. By the end of childhood, at about age 12, most children have developed a self-concept—an understanding and assessment of who they are. Parents often wonder when and how this sense of self develops. “Is my baby girl aware of herself—does she know she is a person distinct from everyone else?”

Of course we cannot ask the baby directly, but we can capitalize on what she can do—letting her behavior provide clues to the beginnings of her self-awareness. In 1877, biologist Charles Darwin offered one idea: Self-awareness begins when we recognize ourselves in a mirror. To see whether a child recognizes that the girl in the mirror is indeed herself, researchers sneakily dabbed color on her nose. At about 6 months, children reach out to touch their mirror image as if it were another child (Courage & Howe, 2002; Damon & Hart, 1982, 1988, 1992). By 15 to 18 months, they begin to touch their own noses when they see the colored spot in the mirror (Butterworth, 1992; Gallup & Suarez, 1986). Apparently, 18-month-olds have a schema of how their face should look, and they wonder, “What is that spot doing on my face?”

By school age, children’s self-concept has blossomed into more detailed descriptions that include their gender, group memberships, psychological traits, and similarities and differences compared with other children (Newman & Ruble, 1988; Stipek, 1992). They come to see themselves as good and skillful in some ways but not others. They form a concept of which traits, ideally, they would like to have. By age 8 or 10, their self-image is quite stable.

Children’s views of themselves affect their actions. Children who form a positive self-concept are more confident, independent, optimistic, assertive, and sociable (Maccoby, 1980). So how can parents encourage a positive yet realistic self-concept?

Parenting Styles

15-8 What are three parenting styles, and how do children’s traits relate to them?

Some parents spank, some reason. Some are strict, some are lax. Some show little affection, some liberally hug and kiss. Do such differences in parenting styles affect children?

The most heavily researched aspect of parenting has been how, and to what extent, parents seek to control their children. Investigators have identified three parenting styles:

- Authoritarian parents are coercive. They impose rules and expect obedience: “Don’t interrupt.” “Keep your room clean.” “Don’t stay out late or you’ll be grounded.” “Why? Because I said so.”

- Permissive parents are unrestraining. They make few demands and use little punishment. They may be indifferent, unresponsive, or unwilling to set limits.

- Authoritative parents are confrontive. They are both demanding and responsive. They exert control by setting rules, but, especially with older children, they encourage open discussion and allow exceptions.

Too hard, too soft, and just right, these styles have been called, especially by pioneering researcher Diana Baumrind and her followers. Research indicates that children with the highest self-esteem, self-reliance, and social competence usually have warm, concerned, authoritative parents (Baumrind, 1996, 2013; Buri et al., 1988; Coopersmith, 1967). Those with authoritarian parents tend to have less social skill and self-esteem, and those with permissive parents tend to be more aggressive and immature. The participants in most studies have been middle-class White families, and some critics suggest that effective parenting may vary by culture. Yet studies with families in more than 200 cultures worldwide have confirmed the social and academic correlates of loving and authoritative parenting (Rohner & Veneziano, 2001; Sorkhabi, 2005; Steinberg & Morris, 2001). For example, two studies of thousands living in Germany found that those whose parents had maintained a curfew exhibited better adjustment and greater achievements in young adulthood than did those with permissive parents (Haase et al., 2008). And the effects are stronger when children are embedded in authoritative communities with connected adults who model a good life (Commission on Children at Risk, 2003).

A word of caution: The association between certain parenting styles (being firm but open) and certain childhood outcomes (social competence) is correlational. Correlation is not causation. Here are two possible alternative explanations for this parenting-competence link:

- Children’s traits may influence parenting. Parental warmth and control vary somewhat from child to child, even in the same family (Holden & Miller, 1999; Klahr & Burt, 2014). Perhaps socially mature, agreeable, easygoing children evoke greater trust and warmth from their parents. Twin studies have supported this possibility (Kendler, 1996).

- Some underlying third factor may be at work. Perhaps, for example, competent parents and their competent children share genes that predispose social competence. Twin studies have also supported this possibility (South et al., 2008).

Have you ever wondered about the effects of children on their parents’ well-being? Try LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Having Children Relates to Being Happier?

Parents who struggle with conflicting advice should remember that all advice reflects the advice-giver’s values. For parents who prize unquestioning obedience, or whose children live in dangerous environments, an authoritarian style may have the desired effect. For those who value children’s sociability and self-reliance, authoritative firm-but-open parenting is advisable.

The investment in raising a child buys many years not only of joy and love but of worry and irritation. Yet for most people who become parents, a child is one’s biological and social legacy—one’s personal investment in the human future. To paraphrase psychiatrist Carl Jung, we reach backward into our parents and forward into our children, and through their children into a future we will never see, but about which we must therefore care.

“You are the bows from which your children as living arrows are sent forth.”

Kahlil Gibran, The Prophet, 1923

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- The three parenting styles have been called “too hard, too soft, and just right.” Which one is “too hard,” which one “too soft,” and which one “just right,” and why?

The authoritarian style would be too hard, the permissive style too soft, and the authoritative style just right. Parents using the authoritative style tend to have children with high self-esteem, selfreliance, and social competence.