16.2 Cognitive Development

16-2 How did Piaget, Kohlberg, and later researchers describe adolescent cognitive and moral development?

“When the pilot told us to brace and grab our ankles, the first thing that went through my mind was that we must all look pretty stupid.”

Jeremiah Rawlings, age 12, after a 1989 DC-10 crash in Sioux City, Iowa

During the early teen years, reasoning is often self-focused. Adolescents may think their private experiences are unique, something parents just could not understand: “But, Mom, you don’t really know how it feels to be in love” (Elkind, 1978). Capable of thinking about their own thinking, and about other people’s thinking, they also begin imagining what others are thinking about them. (They might worry less if they understood their peers’ similar self-absorption.) Gradually, though, most begin to reason more abstractly.

206

Developing Reasoning Power

When adolescents achieve the intellectual summit that Jean Piaget called formal operations, they apply their new abstract reasoning tools to the world around them. They may think about what is ideally possible and compare that with the imperfect reality of their society, their parents, and themselves. They may debate human nature, good and evil, truth and justice. Their sense of what’s fair changes from simple equality to equity—to what’s proportional to merit (Almås et al., 2010). Having left behind the concrete images of early childhood, they may now seek a deeper conception of God and existence (Boyatzis, 2012; Elkind, 1970). Reasoning hypothetically and deducing consequences also enables adolescents to detect inconsistencies and spot hypocrisy in others’ reasoning. This can lead to heated debates with parents and silent vows never to lose sight of their own ideals (Peterson et al., 1986).

Developing Morality

Two crucial tasks of childhood and adolescence are discerning right from wrong and developing character—the psychological muscles for controlling impulses. To be a moral person is to think morally and act accordingly. Jean Piaget and Lawrence Kohlberg proposed that moral reasoning guides moral actions. A newer view builds on psychology’s game-changing recognition that much of our functioning occurs not on the “high road” of deliberate, conscious thinking but on the “low road,” unconscious and automatic.

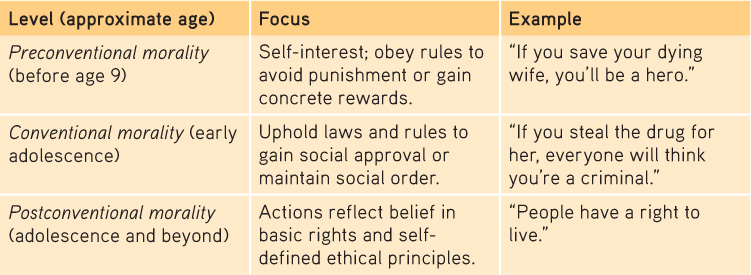

Moral ReasoningPiaget (1932) believed that children’s moral judgments build on their cognitive development. Agreeing with Piaget, Lawrence Kohlberg (1981, 1984) sought to describe the development of moral reasoning, the thinking that occurs as we consider right and wrong. Kohlberg posed moral dilemmas (for example, whether a person should steal medicine to save a loved one’s life) and asked children, adolescents, and adults whether the action was right or wrong. His analysis of their answers led him to propose three basic levels of moral thinking: preconventional, conventional, and postconventional (TABLE 16.1). Kohlberg claimed these levels form a moral ladder. As with all stage theories, the sequence is unvarying. We begin on the bottom rung. Preschoolers, typically identifying with their cultural group, conform to and enforce its moral norms (Schmidt & Tomasello, 2012). Later, we ascend to varying heights. Kohlberg’s critics have noted that his postconventional stage is culturally limited, appearing mostly among people who prize individualism (Eckensberger, 1994; Miller & Bersoff, 1995).

Table 16.1

Table 16.1Kohlberg’s Levels of Moral Thinking

Moral IntuitionPsychologist Jonathan Haidt (2002, 2012) believes that much of our morality is rooted in moral intuitions—“quick gut feelings, or affectively laden intuitions.” According to this intuitionist view, the mind makes moral judgments as it makes aesthetic judgments—quickly and automatically. We feel disgust when seeing people engaged in degrading or subhuman acts. Even a disgusting taste in the mouth heightens people’s disgust over various moral digressions (Eskine et al., 2011). We feel elevation—a tingly, warm, glowing feeling in the chest—when seeing people display exceptional generosity, compassion, or courage. These feelings in turn trigger moral reasoning, says Haidt.

207

One woman recalled driving through her snowy neighborhood with three young men as they passed “an elderly woman with a shovel in her driveway. I did not think much of it, when one of the guys in the back asked the driver to let him off there…. When I saw him jump out of the back seat and approach the lady, my mouth dropped in shock as I realized that he was offering to shovel her walk for her.” Witnessing this unexpected goodness triggered elevation: “I felt like jumping out of the car and hugging this guy. I felt like singing and running, or skipping and laughing. I felt like saying nice things about people” (Haidt, 2000).

“Could human morality really be run by the moral emotions,” Haidt wonders, “while moral reasoning struts about pretending to be in control?” Consider the desire to punish. Laboratory games reveal that the desire to punish wrongdoings is mostly driven not by reason (such as an objective calculation that punishment deters crime) but rather by emotional reactions, such as moral outrage (Darley, 2009). After the emotional fact, moral reasoning—our mind’s press secretary—aims to convince us and others of the logic of what we have intuitively felt.

This intuitionist perspective on morality finds support in a study of moral paradoxes. Imagine seeing a runaway trolley headed for five people. All will certainly be killed unless you throw a switch that diverts the trolley onto another track, where it will kill one person. Should you throw the switch? Most say Yes. Kill one, save five.

Now imagine the same dilemma, except that your opportunity to save the five requires you to push a large stranger onto the tracks, where he will die as his body stops the trolley. The logic is the same—kill one, save five?—but most say No. Seeking to understand why, a Princeton research team led by Joshua Greene (2001) used brain imaging to spy on people’s neural responses as they contemplated such dilemmas. Only when given the body-pushing type of moral dilemma did their brain’s emotion areas activate. Thus, our moral judgments provide another example of the two-track mind—of dual processing (Feinberg et al., 2012). Moral reasoning, centered in one brain area, says throw the switch. Our intuitive moral emotions, rooted in other brain areas, override reason when saying don’t push the man.

While the new research illustrates the many ways moral intuitions trump moral reasoning, other research reaffirms the importance of moral reasoning. The religious and moral reasoning of the Amish, for example, shapes their practices of forgiveness, communal life, and modesty (Narvaez, 2010). Joshua Greene (2010) likens our moral cognition to a camera. Usually, we rely on the automatic point-and-shoot. But sometimes we use reason to manually override the camera’s automatic impulse.

208

Moral ActionOur moral thinking and feeling surely affect our moral talk. But sometimes talk is cheap and emotions are fleeting. Morality involves doing the right thing, and what we do also depends on social influences. As political theorist Hannah Arendt (1963) observed, many Nazi concentration camp guards during World War II were ordinary “moral” people who were corrupted by a powerfully evil situation.

Today’s character education programs tend to focus on the whole moral package—thinking, feeling, and doing the right thing. In service-learning programs, teens have tutored, cleaned up their neighborhoods, and assisted older adults. The result? The teens’ sense of competence and desire to serve has increased, and their school absenteeism and dropout rates have diminished (Andersen, 1998; Piliavin, 2003). Moral action feeds moral attitudes.

“It is a delightful harmony when doing and saying go together.”

Michel Eyquem de Montaigne (1533–1592)

A big part of moral development is the self-discipline needed to restrain one’s own impulses—to delay small gratifications now to enable bigger rewards later. In one of psychology’s best-known experiments, Walter Mischel (1988, 1989) gave Stanford nursery school 4-year-olds a choice between a marshmallow now, or two marshmallows when he returned a few minutes later. The children who had the willpower to delay gratification went on to have higher college completion rates and incomes, and less often suffered addiction problems. Moreover, when a sample of Mischel’s marshmallow alums were retested on a new willpower test 40 years later, their differences persisted (Casey et al., 2011).

Our capacity to delay gratification—to pass on small rewards now for bigger rewards later—is basic to our future academic, vocational, and social success. Teachers and parents rate children who delay gratification on a marshmallow-like test as more self-controlled (Duckworth et al., 2013). A preference for large-later rather than small-now rewards minimizes one’s risk of problem gambling, smoking, and delinquency (Callan et al., 2011; Ert et al., 2013; van Gelder et al., 2013). The moral of the story: Delaying gratification—living with one eye on the future—fosters flourishing.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- According to Kohlberg, _______________ morality focuses on self-interest, _______________ morality focuses on self-defined ethical principles, and _______________ morality focuses on upholding laws and social rules.

preconventional; postconventional; conventional