16.3 Social Development

16-3 What are the social tasks and challenges of adolescence?

“Somewhere between the ages of 10 and 13 (depending on how hormone-enhanced their beef was), children entered adolescence, a.k.a. ‘the de-cutening.’”

Jon Stewart et al., Earth (The Book), 2010

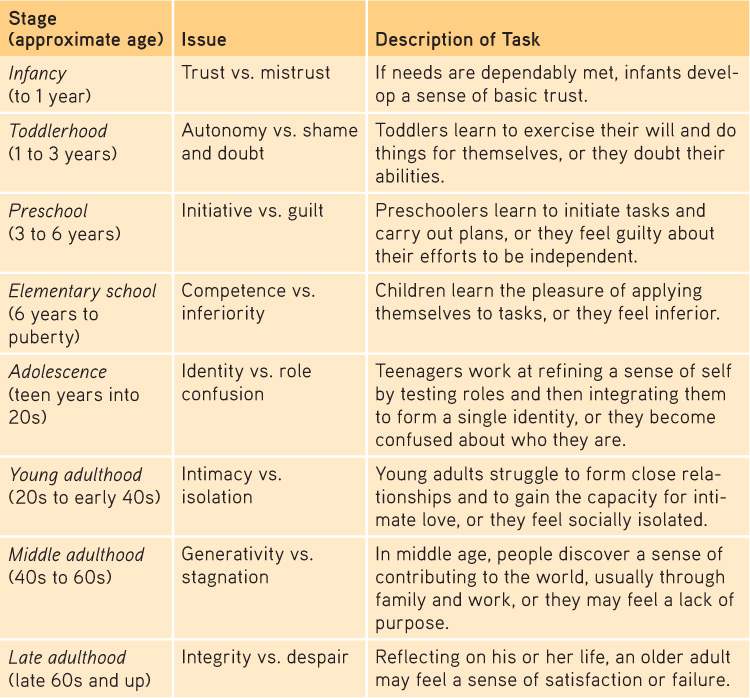

Theorist Erik Erikson (1963) contended that each stage of life has its own psychosocial task, a crisis that needs resolution. Young children wrestle with issues of trust, then autonomy (independence), then initiative. School-age children strive for competence, feeling able and productive. The adolescent’s task is to synthesize past, present, and future possibilities into a clearer sense of self (TABLE 16.2). Adolescents wonder, “Who am I as an individual? What do I want to do with my life? What values should I live by? What do I believe in?” Erikson called this quest the adolescent’s search for identity.

Table 16.2

Table 16.2Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

As sometimes happens in psychology, Erikson’s interests were bred by his own life experience. As the son of a Jewish mother and a Danish Gentile father, Erikson was “doubly an outsider,” reported Morton Hunt (1993, p. 391). He was “scorned as a Jew in school but mocked as a Gentile in the synagogue because of his blond hair and blue eyes.” Such episodes fueled his interest in the adolescent struggle for identity.

Forming an Identity

To refine their sense of identity, adolescents in individualist cultures usually try out different “selves” in different situations. They may act out one self at home, another with friends, and still another at school or online. If two situations overlap—as when a teenager brings friends home—the discomfort can be considerable. The teen asks, “Which self should I be? Which is the real me?” The resolution is a self-definition that unifies the various selves into a consistent and comfortable sense of who one is—an identity.

“Self-consciousness, the recognition of a creature by itself as a ‘self,’ [cannot] exist except in contrast with an ‘other,’ a something which is not the self.”

C. S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain, 1940

For both adolescents and adults, group identities are often formed by how we differ from those around us. When living in Britain, I [DM] become conscious of my Americanness. When spending time with my daughter in Africa, I become conscious of my minority White race. When surrounded by women, I am mindful of my gender identity. For international students, for those of a minority ethnic group or sexual orientation, or for people with a disability, a social identity often forms around their distinctiveness.

Erikson noticed that some adolescents forge their identity early, simply by adopting their parents’ values and expectations. (Traditional, less individualist cultures teach adolescents who they are, rather than encouraging them to decide on their own.) Other adolescents may adopt the identity of a particular peer group—jocks, preps, geeks, band kids, debaters.

Most young people develop a sense of contentment with their lives. A question: Which statement best describes you? “I would choose my life the way it is right now” or, “I wish I were somebody else”? When American teens answered, 81 percent picked the first, and 19 percent the second (Lyons, 2004). Reflecting on their existence, 75 percent of American collegians say they “discuss religion/spirituality” with friends, “pray,” and agree that “we are all spiritual beings” and “search for meaning/purpose in life” (Astin et al., 2004; Bryant & Astin, 2008). This would not surprise Stanford psychologist William Damon and his colleagues (2003), who have contended that a key task of adolescence is to achieve a purpose—a desire to accomplish something personally meaningful that makes a difference to the world beyond oneself.

For an interactive self-assessment of your own identity, see LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Who Am I?

For an interactive self-assessment of your own identity, see LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Who Am I?

Several nationwide studies indicate that young Americans’ self-esteem falls during the early to mid-teen years, and, for girls, depression scores often increase. But then self-image rebounds during the late teens and twenties (Chung et al., 2014; Erol & Orth, 2011; Wagner et al., 2013). Late adolescence is also a time when agreeableness and emotional stability scores increase (Klimstra et al., 2009).

These are the years when many people in industrialized countries begin exploring new opportunities by attending college or working full time. Many college seniors have achieved a clearer identity and a more positive self-concept than they had as first-year students (Waterman, 1988). Collegians who have achieved a clear sense of identity are less prone to alcohol misuse (Bishop et al., 2005).

Erikson contended that adolescent identity formation (which continues into adulthood) is followed in young adulthood by a developing capacity for intimacy, the ability to form emotionally close relationships. Romantic relationships, which tend to be emotionally intense, are reported by some two in three North American 17-year-olds, but fewer among those in collectivist countries such as China (Collins et al., 2009; Li et al., 2010). Those who enjoy high-quality (intimate, supportive) relationships with family and friends tend also to enjoy similarly high-quality romantic relationships in adolescence, which set the stage for healthy adult relationships. Such relationships are, for most of us, a source of great pleasure. When Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi [chick-SENT-me-hi] and Jeremy Hunter (2003) used a beeper to sample the daily experiences of American teens, they found them unhappiest when alone and happiest when with friends. As Aristotle long ago recognized, we humans are “the social animal.” Relationships matter.

Parent and Peer Relationships

16-4 How do parents and peers influence adolescents?

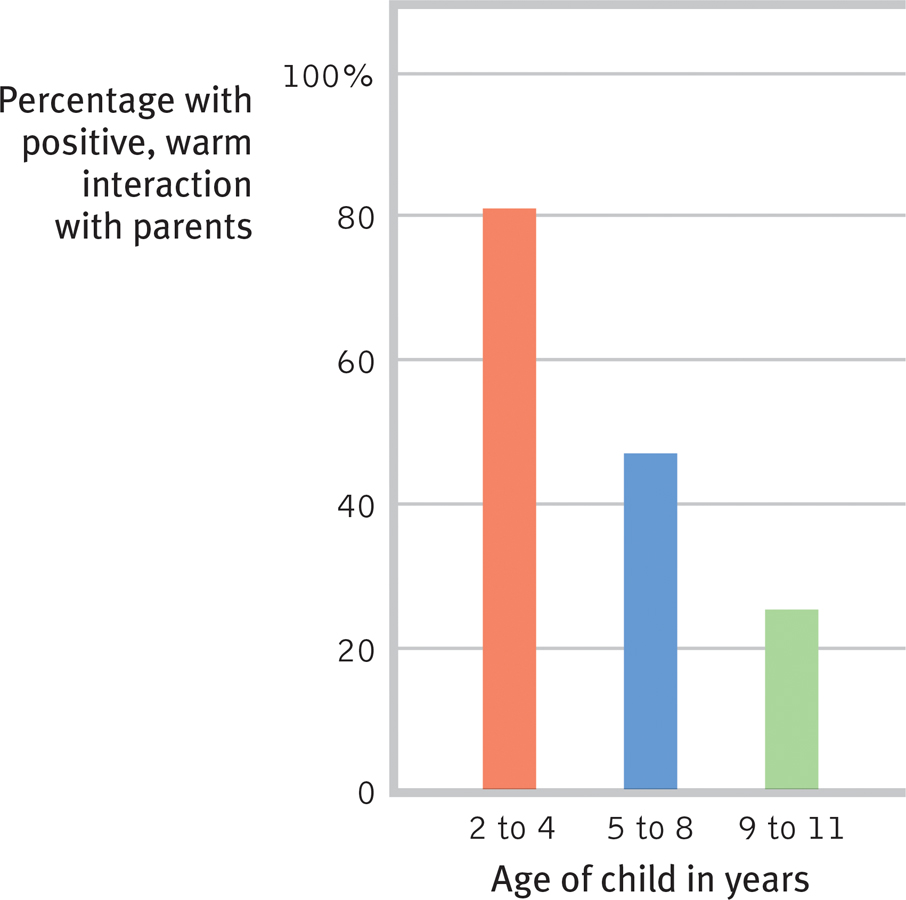

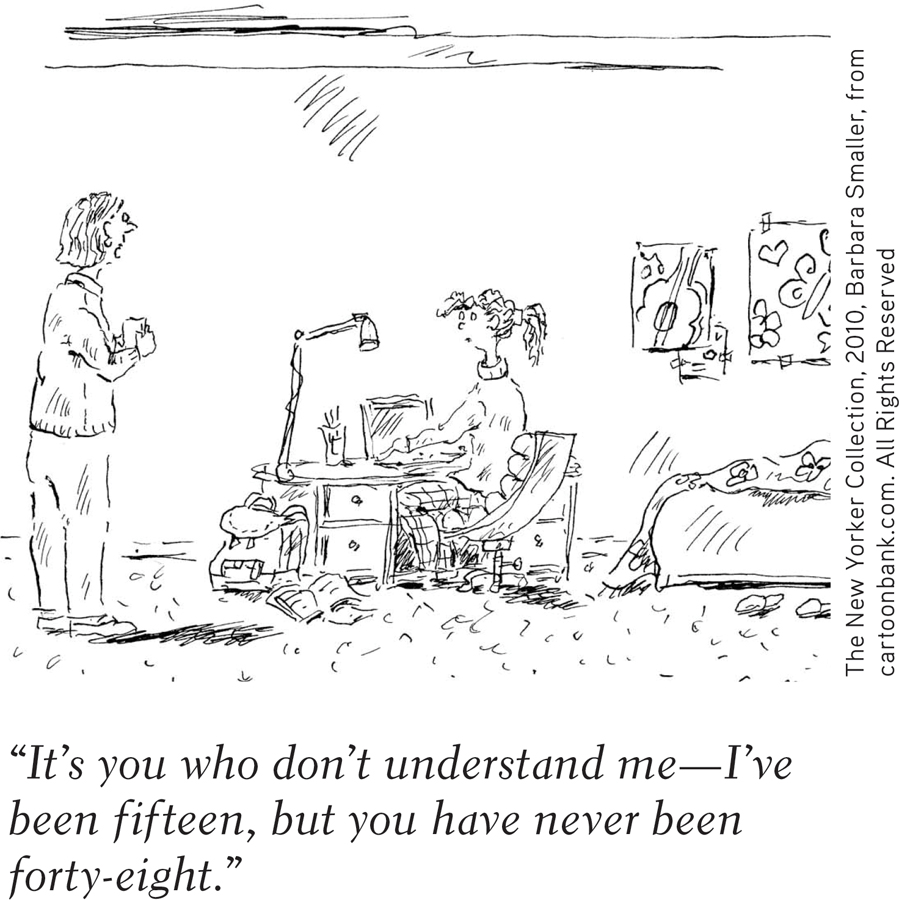

As adolescents in Western cultures seek to form their own identities, they begin to pull away from their parents (Shanahan et al., 2007). The preschooler who can’t be close enough to her mother, who loves to touch and cling to her, becomes the 14-year-old who wouldn’t be caught dead holding hands with Mom. The transition occurs gradually (FIGURE 16.2). By adolescence, parent-child arguments occur more often, usually over mundane things—household chores, bedtime, homework (Tesser et al., 1989). Conflict during the transition to adolescence tends to be greater with first-born than with second-born children, and greater with mothers than with fathers (Burk et al., 2009; Shanahan et al., 2007).

Figure 16.2

Figure 16.2The changing parent-child relationship In a large national study of Canadian families, interviews revealed that the typically close, warm relationships between parents and preschoolers loosened as children became older. (Data from Statistics Canada, 1999.)

For a minority of parents and their adolescents, differences lead to real splits and great stress (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). But most disagreements are at the level of harmless bickering. With sons, the issues often are behavior problems, such as acting out or hygiene, while for daughters, the issues commonly involve relationships, such as dating and friendships (Schlomer et al., 2011). Most adolescents—6000 of them surveyed in 10 countries, from Australia to Bangladesh to Turkey—have said they like their parents (Offer et al., 1988). “We usually get along but … ,” adolescents often reported (Galambos, 1992; Steinberg, 1987).

“I love u guys.”

Emily Keyes’ final text message to her parents before dying in a Colorado school shooting, 2006

Positive parent-teen relations and positive peer relations often go hand in hand. High school girls who had the most affectionate relationships with their mothers tended also to enjoy the most intimate friendships with girlfriends (Gold & Yanof, 1985). And teens who felt close to their parents have tended to be healthy and happy and to do well in school (Resnick et al., 1997). Of course, we can state this correlation the other way: Misbehaving teens are more likely to have tense relationships with parents and other adults.

Adolescence is typically a time of diminishing parental influence and growing peer influence. Asked in a survey if they had “ever had a serious talk” with their child about illegal drugs, 85 percent of American parents answered Yes. But if the parents had indeed given this earnest advice, many teens had apparently tuned it out: Only 45 percent could recall such a talk (Morin & Brossard, 1997).

As we note in other modules, heredity does much of the heavy lifting in forming individual temperament and personality differences, and peer influences do much of the rest. When with peers, teens discount the future and focus more on immediate rewards (O’Brien et al., 2011). Most teens are herd animals. They talk, dress, and act more like their peers than their parents. What their friends are, they often become, and what “everybody’s doing,” they often do.

Part of what everybody’s doing is networking—a lot. Teens rapidly adopt social media. U.S. teens typically send 60 text messages daily and average 300 Facebook friends (Pew, 2012, 2013). Online communication stimulates intimate self-disclosure—both for better (support groups) and for worse (online predators and extremist groups) (Subrahmanyam & Greenfield, 2008; Valkenburg & Peter, 2009; Wilson et al., 2012). Facebook, from a study of all its English-language users, reports this: Among parents and children, 371 days elapse, on average, before they include each other in their circle of self-disclosure (Burke et al., 2013).

Both online and in real life, for those who feel excluded by their peers, the pain is acute. “The social atmosphere in most high schools is poisonously clique-driven and exclusionary,” observed social psychologist Elliot Aronson (2001). Most excluded “students suffer in silence…. A small number act out in violent ways against their classmates.” Those who withdraw are vulnerable to loneliness, low self-esteem, and depression (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Peer approval matters.

Teens have tended to see their parents as having more influence in other areas—for example, in shaping their religious faith and in thinking about college and career choices (Emerging Trends, 1997). A Gallup Youth Survey revealed that most shared their parents’ political views (Lyons, 2005).