17.1 Physical Development

17-1 What physical changes occur during middle and late adulthood?

Like the declining daylight after the summer solstice, our physical abilities—muscular strength, reaction time, sensory keenness, and cardiac output—all begin an almost imperceptible decline in our mid-twenties. Athletes are often the first to notice. World-class sprinters and swimmers peak by their early twenties. Baseball players peak at about age 27—with 60 percent of Most Valuable Player awardees since 1985 coming ±2 years of that (Silver, 2012). Women—who mature earlier than men—peak earlier. But most of us—especially those of us whose daily lives do not require top physical performance—hardly perceive the early signs of decline.

Physical Changes in Middle Adulthood

Post-40 athletes know all too well that physical decline gradually accelerates. As a lifelong basketball player, I [DM] have found myself increasingly not racing for that loose ball. But even diminished vigor is sufficient for normal activities. Moreover, during early and middle adulthood, physical vigor has less to do with age than with a person’s health and exercise habits. Many of today’s physically fit 50-year-olds run four miles with ease, while sedentary 25-year-olds find themselves huffing and puffing up two flights of stairs.

Aging also brings a gradual decline in fertility, especially for women. For a 35- to 39-year-old woman, the chance of getting pregnant after a single act of intercourse is only half that of a woman 19 to 26 (Dunson et al., 2002). Men experience a gradual decline in sperm count, testosterone level, and speed of erection and ejaculation. Women experience menopause, as menstrual cycles end, usually within a few years of age 50. Expectations and attitudes influence the emotional impact of this event. Is it a sign of lost femininity and growing old, or liberation from menstrual periods and fears of pregnancy? For men, too, expectations influence perceptions. Some experience distress related to a perception of declining virility and physical capacities, but most age without such problems.

With age, sexual activity lessens. Nearly 9 in 10 Americans in their late twenties reported having had vaginal intercourse in the past year, compared with 22 percent of women and 43 percent of men who were over 70 (Herbenick et al., 2010; Reece et al., 2010). Nevertheless, most men and women remain capable of satisfying sexual activity, and most express satisfaction with their sex life. This was true of 70 percent of Canadians surveyed (ages 40 to 64) and 75 percent of Finns (ages 65 to 74) (Kontula & Haavio-Mannila, 2009; Wright, 2006). In one survey, 75 percent of respondents reported being sexually active into their 80s (Schick et al., 2010). And in an American Association of Retired Persons sexuality survey, it was not until age 75 or older that most women and nearly half of men reported little sexual desire (DeLamater, 2012; DeLamater & Sill, 2005). Given good health and a willing partner, the flames of desire, though simmered down, live on. As Alex Comfort (1992, p. 240) jested, “The things that stop you having sex with age are exactly the same as those that stop you riding a bicycle (bad health, thinking it looks silly, no bicycle).”

Physical Changes in Late Adulthood

Is old age “more to be feared than death” (Juvenal, Satires)? Or is life “most delightful when it is on the downward slope” (Seneca, Epistulae ad Lucilium)? What is it like to grow old?

Life ExpectancyFrom 1950 to 2011, life expectancy at birth increased worldwide from 46.5 years to 70 years—and to 80 and beyond in some developed countries (WHO, 2014a,b). What a gift—two decades more of life! In China, the United States, Britain, Canada, and Australia (to name some countries where students read this book), life expectancy has risen to 76, 79, 80, 82, and 82 respectively (WHO, 2014). This increasing life expectancy (humanity’s greatest achievement, say some) combines with decreasing birthrates: Older adults are a bigger and bigger population segment, creating an increasing demand for hearing aids, retirement villages, and nursing homes. Today, 1 in 10 people worldwide are 60 or older. The United Nations (2001, 2010) projects that number will double to 2 in 10 by 2050 (and to nearly 4 in 10 in Europe).

“I intend to live forever—so far, so good.”

Comedian Steven Wright

Throughout the life span, males are more prone to dying. Although 126 male embryos begin life for every 100 females, the sex ratio is down to 105 males for every 100 females at birth (Strickland, 1992). During the first year, male infants’ death rates exceed females’ by one-fourth. Worldwide, women outlive men by 4.6 years (WHO, 2014b). (Rather than marrying a man older than themselves, 20-year-old women who want a husband who shares their life expectancy should wait for the 16-year-old boys to mature.) By age 100, women outnumber men 5 to 1.

But few of us live to 100. Disease strikes. The body ages. Its cells stop reproducing. It becomes frail and vulnerable to tiny insults—hot weather, a fall, a mild infection—that at age 20 would have been trivial. Tips of chromosomes, called telomeres, wear down, much as the tip of a shoelace frays. This wear is accelerated by smoking, obesity, or stress. Children who suffer frequent abuse or bullying exhibit shortened telomeres as biological scars (Shalev et al., 2013). As telomeres shorten, aging cells may die without being replaced with perfect genetic replicas (Epel, 2009).

Low stress and good health habits enable longevity, as does a positive spirit. Chronic anger and depression increase our risk of premature death. Researchers have even observed an intriguing death-deferral phenomenon (Shimizu & Pelham, 2008). Across one 15-year-period, the 82,000 deaths on Christmas Day rose to 85,000 on December 26 and 27. The death rate also increases when people reach their birthdays, and when they survive until after other milestones, like the first day of the new millennium.

“For some reason, possibly to save ink, the restaurants had started printing their menus in letters the height of bacteria.”

Dave Barry, Dave Barry Turns Fifty, 1998

Sensory Abilities, Strength, and StaminaAlthough physical decline begins in early adulthood, we are not usually acutely aware of it until later life, when the stairs get steeper, the print gets smaller, and other people seem to mumble more. Visual sharpness diminishes, and distance perception and adaptation to light-level changes are less acute. Muscle strength, reaction time, and stamina also diminish, as do the senses of smell and hearing. In Wales, teens’ loitering around a convenience store has been discouraged by a device that emits an aversive high-pitched sound that almost no one over 30 can hear (Lyall, 2005).

Most stairway falls taken by older people occur on the top step, precisely where the person typically descends from a window-lit hallway into the darker stairwell (Fozard & Popkin, 1978). Our knowledge of aging could be used to design environments that would reduce such accidents (National Research Council, 1990).

With age, the eye’s pupil shrinks and its lens becomes less transparent, reducing the amount of light reaching the retina. A 65-year-old retina receives only about one- third as much light as its 20-year-old counterpart (Kline & Schieber, 1985). Thus, to see as well as a 20-year-old when reading or driving, a 65-year-old needs three times as much light—a reason for buying cars with untinted windshields. This also explains why older people sometimes ask younger people, “Don’t you need better light for reading?”

HealthAs people age, they care less about what their bodies look like and more about how they function. For those growing older, there is both bad and good news about health. The bad news: The body’s disease-fighting immune system weakens, making older adults more susceptible to life-threatening ailments such as cancer and pneumonia. The good news: Thanks partly to a lifetime’s accumulation of antibodies, people over 65 suffer fewer short-term ailments, such as common flu and cold viruses. One study found they were half as likely as 20-year-olds and one-fifth as likely as preschoolers to suffer upper respiratory flu each year (National Center for Health Statistics, 1990).

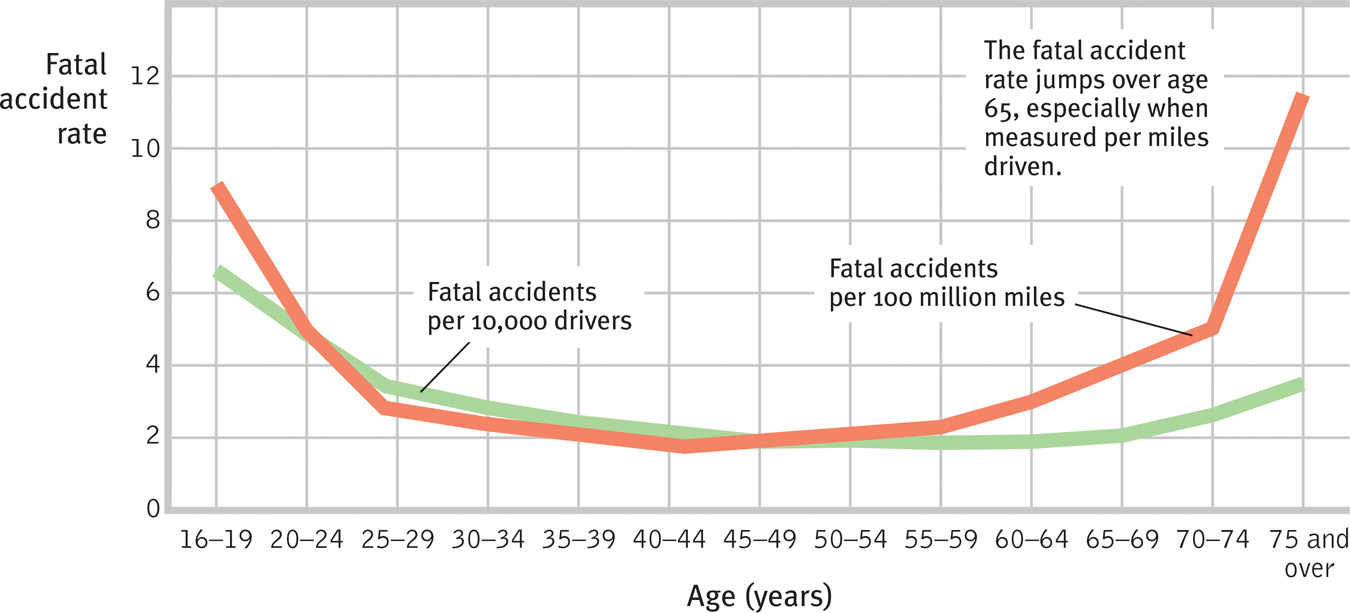

The Aging BrainUp to the teen years, we process information with greater and greater speed (Fry & Hale, 1996; Kail, 1991). But compared with teens and young adults, older people take a bit more time to react, to solve perceptual puzzles, even to remember names (Bashore et al., 1997; Verhaeghen & Salthouse, 1997). The neural processing lag is greatest on complex tasks (Cerella, 1985; Poon, 1987). At video games, most 70-year-olds are no match for a 20-year-old. And, as FIGURE 17.1 indicates, fatal accident rates per mile driven increase sharply after age 75. By age 85, they exceed the 16-year-old level. Older drivers appear to focus well on the road ahead, but attend less to other vehicles approaching from the side (Pollatsek et al., 2012). Nevertheless, because older people drive less, they account for fewer than 10 percent of crashes (Coughlin et al., 2004).

Figure 17.1

Figure 17.1Age and driver fatalities Slowing reactions contribute to increased accident risks among those 75 and older, and their greater fragility increases their risk of death when accidents happen (NHTSA, 2000). Would you favor driver exams based on performance, not age, to screen out those whose slow reactions or sensory impairments indicate accident risk?

Even speech slows (Jacewicz et al. 2009). One research team compared speeches of the renowned psychologist, B. F. Skinner, and observed his speaking rate at ages 58, 73, and 90 as 148, 137, and 106 words per minute, respectively (Epstein, 2012).

Brain regions important to memory begin to atrophy during aging (Schacter, 1996). No wonder older adults, after taking a memory test, feel older: “aging 5 years in 5 minutes,” jested one research report (Hughes et al., 2013). In early adulthood, a small, gradual net loss of brain cells begins, contributing by age 80 to a brain-weight reduction of 5 percent or so. In adolescence, late-maturing frontal lobes help account for teen impulsivity. Late in life, atrophy of the inhibition-controlling frontal lobes seemingly explains older people’s occasional blunt questions and comments (“Have you put on weight?”) (von Hippel, 2007). But good news: The aging brain is plastic, and partly compensates for what it loses by recruiting and reorganizing neural networks (Park & McDonough, 2013). During memory tasks, for example, the left frontal lobes are especially active in young adult brains, while older adult brains use both left and right frontal lobes.

EXERCISE AND AGING And more good news: Exercise slows aging. Active older adults tend to be mentally quick older adults. Physical exercise not only enhances muscles, bones, and energy and helps prevent obesity and heart disease, it maintains the telomeres that protect the chromosome ends (Leslie, 2011).

Exercise also stimulates brain cell development and neural connections, thanks perhaps to increased oxygen and nutrient flow (Erickson et al., 2013; Pereira et al., 2007). Sedentary older adults randomly assigned to aerobic exercise programs exhibit enhanced memory, sharpened judgment, and reduced risk of significant cognitive decline (DeFina et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2010; Nagamatsu et al., 2013). In aging brains, exercise reduces brain shrinkage (Gow et al., 2012). It promotes neurogenesis (the birth of new nerve cells) in the hippocampus, a brain region important for memory (Cherkas et al., 2008; Erickson, 2009; Pereira et al., 2007). And it increases the cellular mitochondria that help power both muscles and brain cells (Steiner et al., 2011). We are more likely to rust from disuse than to wear out from overuse. Fit bodies support fit minds.