18.3 Sensory Adaptation

18-5 What is the function of sensory adaptation?

Entering your neighbors’ living room, you smell a musty odor. You wonder how they endure it, but within minutes you no longer notice it. Sensory adaptation has come to your rescue. When we are constantly exposed to an unchanging stimulus, we become less aware of it because our nerve cells fire less frequently. (To experience sensory adaptation, move your watch up your wrist an inch: You will feel it—but only for a few moments.)

“We need above all to know about changes; no one wants or needs to be reminded 16 hours a day that his shoes are on.”

Neuroscientist David Hubel (1979)

Why, then, if we stare at an object without flinching, does it not vanish from sight? Because, unnoticed by us, our eyes are always moving. This continual flitting from one spot to another ensures that stimulation on the eyes’ receptors continually changes (FIGURE 18.4).

Figure 18.4

Figure 18.4The jumpy eye Our gaze jumps from one spot to another every third of a second or so, as eye-tracking equipment illustrated as a person looked at this photograph of Edinburgh’s Princes Street Gardens (Henderson, 2007). The circles represent visual fixations, and the numbers indicate the time of fixation in milliseconds (300 milliseconds = 3/10ths of a second).

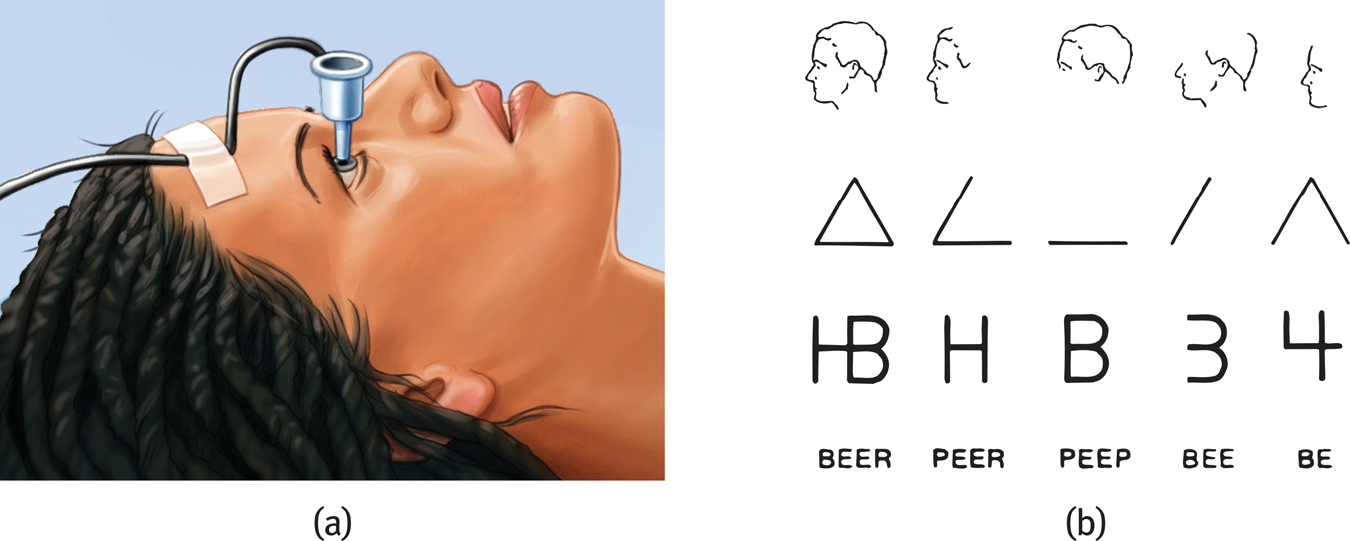

What if we actually could stop our eyes from moving? Would sights seem to vanish, as odors do? To find out, psychologists have devised ingenious instruments that maintain a constant image on the eye’s inner surface. Imagine that we have fitted a volunteer, Mary, with one of these instruments—a miniature projector mounted on a contact lens (FIGURE 18.5a). When Mary’s eye moves, the image from the projector moves as well. So everywhere that Mary looks, the scene is sure to go.

Figure 18.5

Figure 18.5Sensory adaptation: now you see it, now you don’t! (a) A projector mounted on a contact lens makes the projected image move with the eye. (b) Initially, the person sees the stabilized image, but soon she sees fragments fading and reappearing. (From “Stabilized images on the retina,” by R. M. Pritchard. Copyright © 1961 Scientific American, Inc. All rights reserved.)

If we project images through this instrument, what will Mary see? At first, she will see the complete image. But within a few seconds, as her sensory system begins to fatigue, things get weird. Bit by bit, the image vanishes, only to reappear and then disappear—often in fragments (FIGURE 18.5a).

Although sensory adaptation reduces our sensitivity, it offers an important benefit: freedom to focus on informative changes in our environment without being distracted by background chatter. Stinky or heavily perfumed people don’t notice their odor because, like you and me, they adapt to what’s constant and detect only change. Our sensory receptors are alert to novelty; bore them with repetition and they free our attention for more important things. The point to remember: We perceive the world not exactly as it is, but as it is useful for us to perceive it.

Our sensitivity to changing stimulation helps explain television’s attention-grabbing power. Cuts, edits, zooms, pans, sudden noises—all demand attention. The phenomenon is irresistible even to TV researchers. One noted that during conversations, “I cannot for the life of me stop from periodically glancing over to the screen” (Tannenbaum, 2002).

Sensory adaptation even influences how we perceive emotions. By creating a 50-50 morphed blend of an angry face and a scared face, researchers showed that our visual system adapts to a static facial expression by becoming less responsive to it (Butler et al., 2008; FIGURE 18.6). The effect is created by our brain, not our retinas. We know this because the illusion also works when we view either side image with one eye, and the center image with the other eye.

Figure 18.6

Figure 18.6Emotion adaptation Gaze at the angry face on the left for 20 to 30 seconds, then look at the center face (looks scared, yes?). Then gaze at the scared face on the right for 20 to 30 seconds, before returning to the center face (now looks angry, yes?). (From Butler et al., 2008.)

Sensory adaptation and sensory thresholds are important ingredients in our perceptions of the world around us. Much of what we perceive comes not just from what’s “out there” but also from what’s behind our eyes and between our ears.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Why is it that after wearing shoes for a while, you cease to notice them (until questions like this draw your attention back to them)?

The shoes provide constant stimulation. Sensory adaptation allows us to focus on changing stimuli.