18.4 Perceptual Set

18-6 How do our expectations, contexts, motivation, and emotions influence our perceptions?

To see is to believe. As we less fully appreciate, to believe is to see. Through experience, we come to expect certain results. Those expectations may give us a perceptual set, a set of mental tendencies and assumptions that affects (top-down) what we hear, taste, feel, and see.

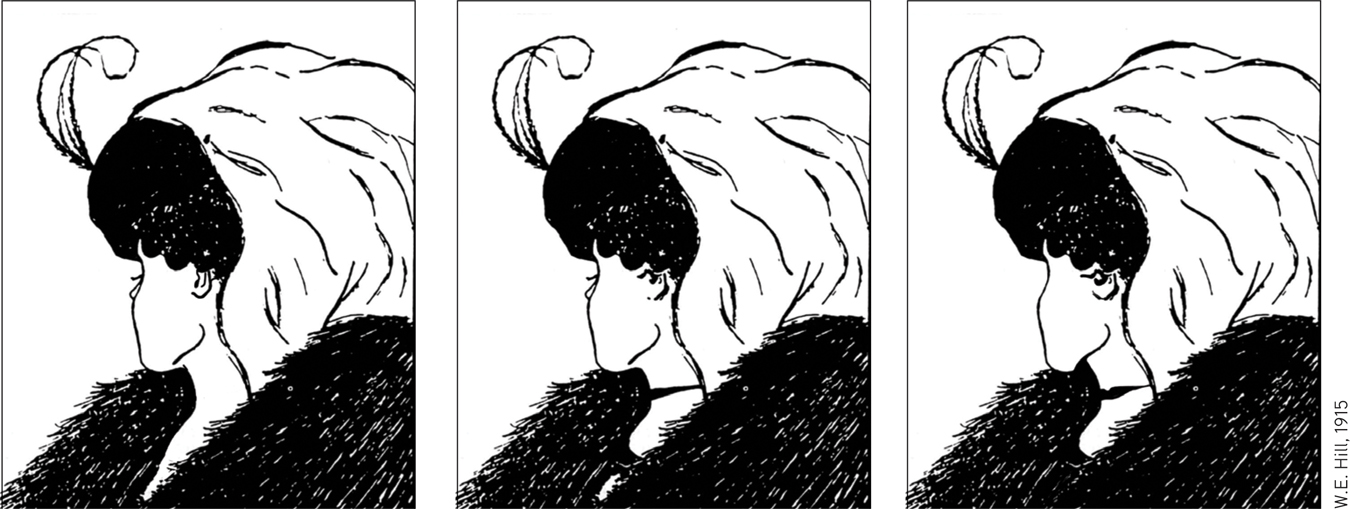

Consider: Is the center image in FIGURE 18.7 an old or young woman? What we see in such a drawing can be influenced by first looking at either of the two unambiguous versions (Boring, 1930).

Figure 18.7

Figure 18.7Perceptual set Show a friend either the left or right image. Then show the center image and ask, “What do you see?” Whether your friend reports seeing an old woman’s face or young woman’s profile may depend on which of the other two drawings was viewed first. In each of those images, the meaning is clear, and it will establish perceptual expectations.

Everyday examples of perceptual set—of “mind over mind”—abound. In 1972, a British newspaper published unretouched photographs of a “monster” in Scotland’s Loch Ness—“the most amazing pictures ever taken,” stated the paper. If this information creates in you the same expectations it did in most of the paper’s readers, you, too, will see the monster in a similar photo in FIGURE 18.8. But when a skeptical researcher approached the original photos with different expectations, he saw a curved tree limb—as had others the day that photo was shot (Campbell, 1986). With this different perceptual set, you may now notice that the object is floating motionless, with ripples outward in all directions—hardly what we would expect of a swimming monster.

Figure 18.8

Figure 18.8Believing is seeing What do you perceive? Is this Nessie, the Loch Ness monster, or a log?

There

Are Two

Errors in The

The Title Of

This Book

Book by Robert M. Martin, 2011

Did you perceive what you expected in this title—

The title’s first error is its repeated “the.” Its ironic second error is its misstatement that there are two errors, when there is only one.

Perceptual set can also affect what we hear. Consider the kindly airline pilot who, on a takeoff run, looked over at his sad co-pilot and said, “Cheer up.” Expecting to hear the usual “Gear up,” the co-pilot promptly raised the wheels—before they left the ground (Reason & Mycielska, 1982).

Perceptual set similarly affects taste. One experiment invited bar patrons to sample free beer (Lee et al., 2006). When researchers added a few drops of vinegar to a brand-name beer, the tasters preferred it—unless they had been told they were drinking vinegar-laced beer. Then they expected, and usually experienced, a worse taste. In another experiment, preschool children, by a 6-to-1 margin, thought french fries tasted better when served in a McDonald’s bag rather than a plain white bag (Robinson et al., 2007).

What determines our perceptual set? Through experience we form concepts, or schemas, that organize and interpret unfamiliar information. Our preexisting schemas for monsters and tree trunks influence how we apply top-down processing to interpret ambiguous sensations.

“We hear and apprehend only what we already half know.”

Henry David Thoreau, Journal, 1860

In everyday life, stereotypes about gender (another instance of perceptual set) can color perception. Without the obvious cues of pink or blue, people will struggle over whether to call the new baby “he” or “she.” But told an infant is “David,” people (especially children) have perceived “him” as bigger and stronger than if the same infant was called “Diana” (Stern & Karraker, 1989). Some differences, it seems, exist merely in the eyes of their beholders.