18.6 Motivation and Emotion

Perceptions are influenced, top-down, not only by our expectations and by the context, but also by our emotions and motivation.

Hearing sad rather than happy music can predispose people to perceive a sad meaning in spoken homophonic words—mourning rather than morning, die rather than dye, pain rather than pane (Halberstadt et al., 1995). When angry, people more often perceive neutral objects as guns (Baumann & Steno, 2010). After listening to irritating (and anger-cuing) music, they also perceive a harmful action such as robbery as more serious (Seidel & Prinz, 2013).

Dennis Proffitt (2006a,b; Schnall et al., 2008) and others have demonstrated the power of emotions with other clever experiments showing that

- walking destinations look farther away to those who have been fatigued by prior exercise.

- a hill looks steeper to those who are wearing a heavy backpack or have just been exposed to sad, heavy classical music rather than light, bouncy music. As with so many of life’s challenges, a hill also seems less steep to those with a friend beside them.

- a target seems farther away to those throwing a heavy rather than a light object at it.

- even a softball appears bigger when you are hitting well, observed Jessica Witt and Proffitt (2005), after asking players to choose a circle the size of the ball they had just hit well or poorly. (There’s also a reciprocal phenomenon: Seeing a target as bigger—as happens when athletes focus directly on a target—improves performance [Witt et al., 2012].)

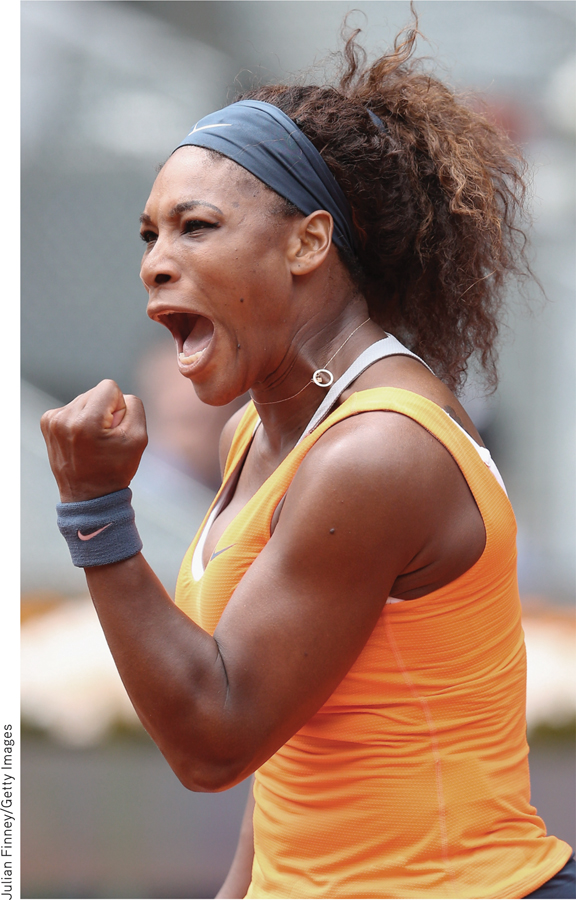

Figure 18.11

Figure 18.11Context makes clearer Serena Williams is celebrating! (Example from Barrett et al., 2011.)

“When you’re hitting the ball, it comes at you looking like a grapefruit. When you’re not, it looks like a blackeyed pea.”

Former major league baseball player George Scott

Motives also matter. Desired objects, such as a water bottle when thirsty, seem closer (Balcetis & Dunning, 2010). This perceptual bias energizes our going for it. Our motives also direct our perception of ambiguous images.

Emotions and motives color our social perceptions, too. People more often perceive solitary confinement, sleep deprivation, and cold temperatures as “torture” when experiencing a small dose of such themselves (Nordgren et al., 2011). Spouses who feel loved and appreciated perceive less threat in stressful marital events—“He’s just having a bad day” (Murray et al., 2003). Professional referees, if told a soccer team has a history of aggressive behavior, will assign more penalty cards after watching videotaped fouls (Jones et al., 2002). The moral of these stories: To believe is, indeed, to see.