1.3 Contemporary Psychology

1-

The young science of psychology developed from the more established fields of philosophy and biology. Wundt was both a philosopher and a physiologist. James was an American philosopher. Freud was an Austrian physician. Ivan Pavlov, who pioneered the study of learning, was a Russian physiologist. Jean Piaget, the last century’s most influential observer of children, was a Swiss biologist. These “Magellans of the mind,” as Morton Hunt (1993) has called them, illustrate psychology’s origins in many disciplines and many countries.

Like those pioneers, today’s psychologists are citizens of many lands. The International Union of Psychological Science has 182 member nations, from Albania to Zimbabwe. In China, the first university psychology department began in 1978; by 2008 there were nearly 200 (Han, 2008; Tversky, 2008). Moreover, thanks to international publications, joint meetings, and the Internet, collaboration and communication now cross borders. Psychology is growing and it is globalizing. The story of psychology—

Evolutionary Psychology and Behavior Genetics

Are our human traits present at birth, or do they develop through experience? This has been psychology’s biggest and most persistent issue. But the debate over the nature-nurture issue is ancient. The Greek philosopher Plato (428–

In the 1600s, European philosophers rekindled the debate. John Locke argued that the mind is a blank slate on which experience writes. René Descartes disagreed, believing that some ideas are innate. Descartes’ views gained support from a curious naturalist two centuries later. In 1831, an indifferent student but ardent collector of beetles, mollusks, and shells set sail on a historic round-

The nature–

Such debates continue. Yet over and over again we will see that in contemporary science the nature–

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is natural selection?

This is the process by which nature selects from chance variations the traits that best enable an organism to survive and reproduce in a particular environment.

- What is contemporary psychology’s position on the nature–nurture debate?

Psychological events often stem from the interaction of nature and nurture, rather than from either of them acting alone.

Cross-Cultural and Gender Psychology

What can we learn about people in general from psychological studies done in one time and place—

“All people are the same; only their habits differ.”

Confucius, 551–479 B.C.E

It is also true, however, that our shared biological heritage unites us as a universal human family. The same underlying processes guide people everywhere:

- People diagnosed with specific learning disorder (formerly called dyslexia) exhibit the same brain malfunction whether they are Italian, French, or British (Paulesu et al, 2001).

- Variation in languages may impede communication across cultures. Yet all languages share deep principles of grammar, and people from opposite hemispheres can communicate with a smile or a frown.

- People in different cultures vary in feelings of loneliness. But across cultures, loneliness is magnified by shyness, low self-esteem, and being unmarried (Jones et al., 1985; Rokach et al., 2002).

We are each in certain respects like all others, like some others, and like no other. Studying people of all races and cultures helps us discern our similarities and our differences, our human kinship and our diversity.

is a research-based online learning tool that will help you excel in this course. Visit LaunchPad to take advantage of self-tests, interactive simulations, and

is a research-based online learning tool that will help you excel in this course. Visit LaunchPad to take advantage of self-tests, interactive simulations, and  HOW WOULD YOU KNOW? activities. For a 1-minute introduction to LaunchPad, including how to get in and use its helpful resources, go to http://tinyurl.com/LaunchPadIntro. In LaunchPad, you will find resources collected by module groups. resources may be found by clicking on the “Resources” star in the left column.

HOW WOULD YOU KNOW? activities. For a 1-minute introduction to LaunchPad, including how to get in and use its helpful resources, go to http://tinyurl.com/LaunchPadIntro. In LaunchPad, you will find resources collected by module groups. resources may be found by clicking on the “Resources” star in the left column.

You will see throughout this book that gender matters, too. Researchers report gender differences in what we dream, in how we express and detect emotions, and in our risk for alcohol use disorder, depression, and eating disorders. Gender differences fascinate us, and studying them is potentially beneficial. For example, many researchers have observed that women carry on conversations more readily to build relationships, while men talk more to give information and advice (Tannen, 2001). Knowing this difference can help us prevent conflicts and misunderstandings in everyday relationships.

But again, psychologically as well as biologically, women and men are overwhelmingly similar. Whether female or male, we learn to walk at about the same age. We experience the same sensations of light and sound. We feel the same pangs of hunger, desire, and fear. We exhibit similar overall intelligence and well-

The point to remember: Even when specific attitudes and behaviors vary by gender or across cultures, as they often do, the underlying causes are much the same.

Positive Psychology

Psychology’s first hundred years focused on understanding and treating troubles, such as abuse and anxiety, depression and disease, prejudice and poverty. Much of today’s psychology continues the exploration of such challenges. Without slighting the need to repair damage and cure disease, Martin Seligman and others (2002, 2005, 2011) have called for more research on human flourishing. These psychologists call their approach positive psychology. They believe that happiness is a by-

For an excellent tour of psychology’s roots, view the 9.5-minute Video: The History of Psychology.

For an excellent tour of psychology’s roots, view the 9.5-minute Video: The History of Psychology.

Psychology’s Three Main Levels of Analysis

1-

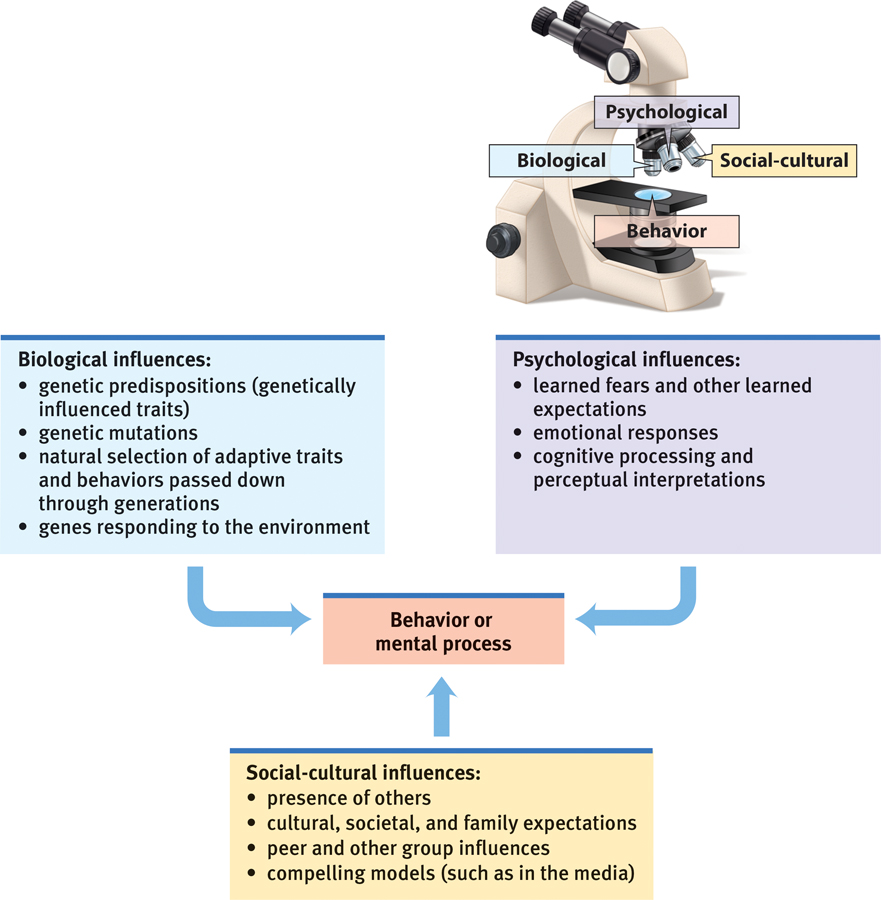

Each of us is a complex system that is part of a larger social system. But each of us is also composed of smaller systems, such as our nervous system and body organs, which are composed of still smaller systems—

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.1Biopsychosocial approach This integrated viewpoint incorporates various levels of analysis and offers a more complete picture of any given behavior or mental process.

These tiered systems suggest different levels of analysis, which offer complementary outlooks. It’s like explaining horrific school shootings. Is it because the shooters have brain disorders or genetic tendencies that cause them to be violent? Because they have been rewarded for violent behavior? Because we live in a gun-

Each level provides a valuable playing card in psychology’s explanatory deck. It’s a vantage point for looking at a behavior or mental process, yet each by itself is incomplete. Like different academic disciplines, psychology’s varied perspectives ask different questions and have their own limits. One perspective may stress the biological, psychological, or social-

- Someone working from a neuroscience perspective might study brain circuits that cause us to be red in the face and “hot under the collar.”

- Someone working from the evolutionary perspective might analyze how anger facilitated the survival of our ancestors’ genes.

- Someone working from the behavior genetics perspective might study how heredity and experience influence our individual differences in temperament.

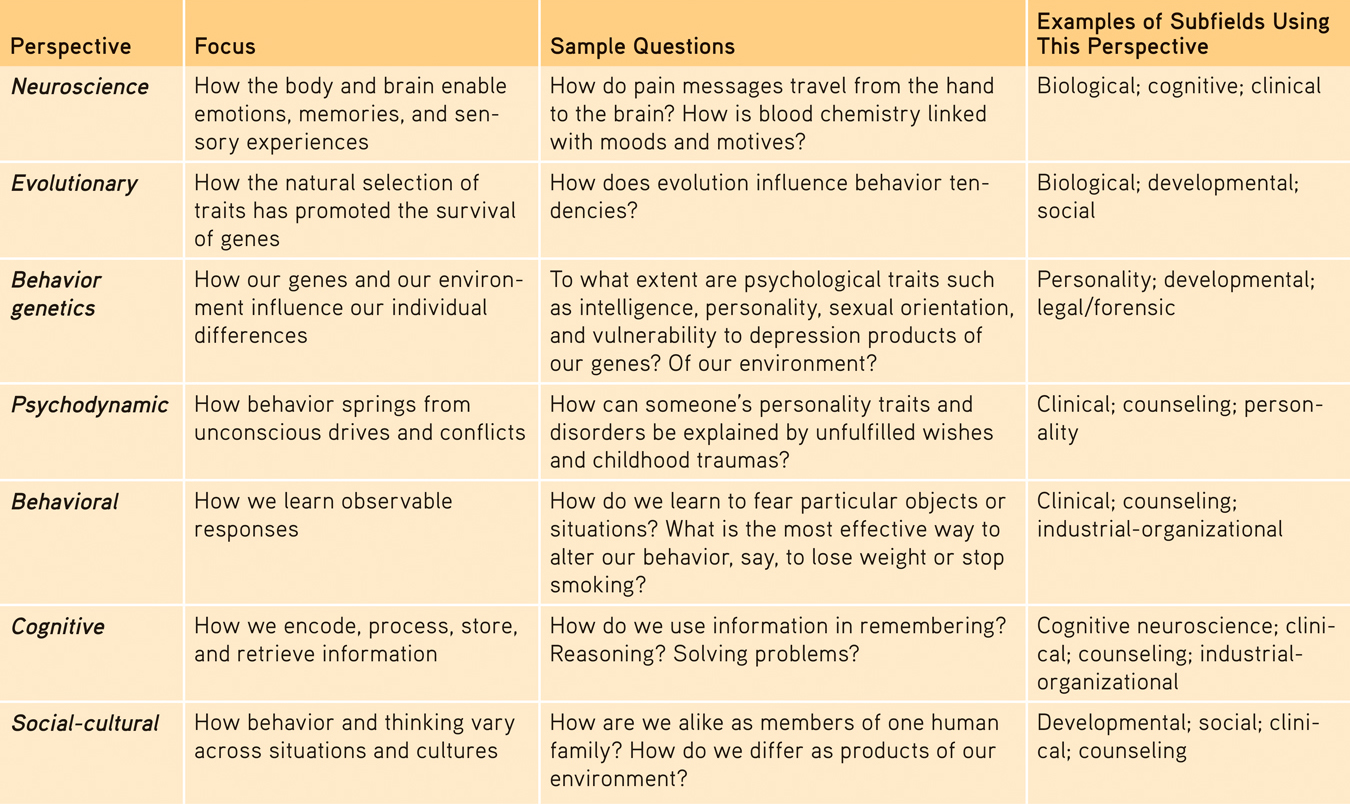

Table 1.1

Table 1.1Psychology’s Current Perspectives

- Someone working from the psychodynamic perspective might view an outburst as an outlet for unconscious hostility.

- Someone working from the behavioral perspective might attempt to determine which external stimuli trigger angry responses or aggressive acts.

- Someone working from the cognitive perspective might study how our interpretation of a situation affects our anger and how our anger affects our thinking.

- Someone working from the social-cultural perspective might explore how expressions of anger vary across cultural contexts.

The point to remember: Like two-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What advantage do we gain by using the biopsychosocial approach in studying psychological events?

By incorporating different levels of analysis, the biopsychosocial approach can provide a more complete view than any one perspective could offer.

- The __________ perspective in psychology focuses on how behavior and thought differ from situation to situation and from culture to culture, while the __________ perspective emphasizes observation of how we respond to and learn in different situations.

social-

Psychology’s Subfields

1-

Picturing a chemist at work, you may envision a white-

- a white-coated scientist probing a rat’s brain.

- an intelligence researcher measuring how quickly an infant shows boredom by looking away from a familiar picture.

- an executive evaluating a new “healthy life styles” training program for employees.

- someone at a computer analyzing data on whether adopted teens’ temperaments more closely resemble those of their adoptive parents or their biological parents.

- a therapist listening carefully to a depressed client’s thoughts.

- a traveler visiting another culture and collecting data on variations in human values and behaviors.

- a teacher or writer sharing the joy of psychology with others.

The cluster of subfields we call psychology is a meeting ground for different disciplines. “Psychology is a hub scientific discipline,” said Association for Psychological Science president John Cacioppo (2007). Thus, it’s a perfect home for those with wide-

Some psychologists conduct basic research that builds psychology’s knowledge base. We will meet a wide variety of such researchers, including biological psychologists exploring the links between brain and mind; developmental psychologists studying our changing abilities from womb to tomb; cognitive psychologists experimenting with how we perceive, think, and solve problems; personality psychologists investigating our persistent traits; and social psychologists exploring how we view and affect one another.

These and other psychologists also may conduct applied research, tackling practical problems. Industrial-

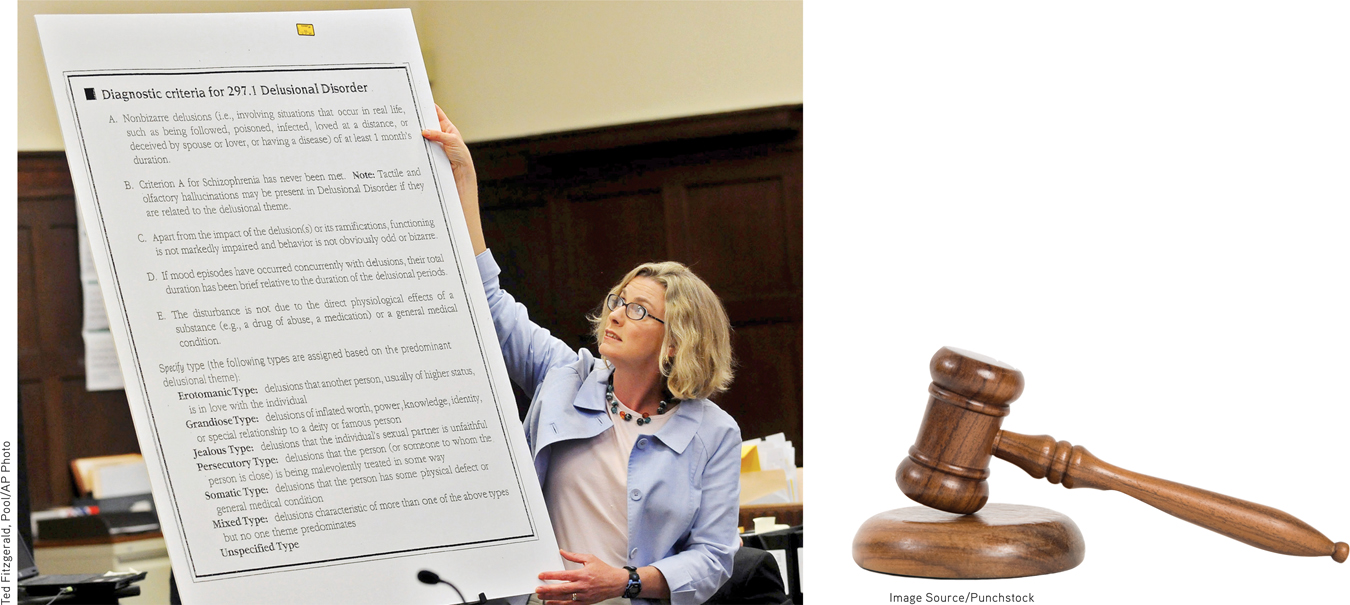

Although most psychology textbooks focus on psychological science, psychology is also a helping profession devoted to such practical issues as how to have a happy marriage, how to overcome anxiety or depression, and how to raise thriving children. As a science, psychology at its best bases such interventions on evidence of effectiveness. Counseling psychologists help people to cope with challenges and crises (including academic, vocational, and marital issues) and to improve their personal and social functioning. Clinical psychologists assess and treat people with mental, emotional, and behavior disorders. Both counseling and clinical psychologists administer and interpret tests, provide counseling and therapy, and sometimes conduct basic and applied research. By contrast, psychiatrists, who also may provide psychotherapy, are medical doctors licensed to prescribe drugs and otherwise treat physical causes of psychological disorders.

Rather than seeking to change people to fit their environment, community psychologists work to create social and physical environments that are healthy for all (Bradshaw et al., 2009; Trickett, 2009). For example, if school bullying is a problem, some psychologists will seek to change the bullies. Knowing that many students struggle with the transition from elementary to middle school, they might train individual kids how to cope. Community psychologists instead seek ways to adapt the school experience to early adolescent needs. To prevent bullying, they might study how the school and neighborhood foster bullying and how to increase bystander intervention (Polanin et al., 2012).

With perspectives ranging from the biological to the social, and with settings from the laboratory to the clinic, psychology relates to many fields. Psychologists teach in medical schools, law schools, and theological seminaries, and they work in hospitals, factories, and corporate offices. They engage in interdisciplinary studies, such as psychohistory (the psychological analysis of historical characters), psycholinguistics (the study of language and thinking), and psychoceramics (the study of crackpots).1

Want to learn more? See Appendix B, Subfields of Psychology, at the end of this book, and go to LaunchPad’s regularly updated Careers in Psychology resource to learn about the many interesting options available to those with bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees in psychology.

Want to learn more? See Appendix B, Subfields of Psychology, at the end of this book, and go to LaunchPad’s regularly updated Careers in Psychology resource to learn about the many interesting options available to those with bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees in psychology.

Psychology also influences modern culture. Knowledge transforms us. Learning about the solar system and the germ theory of disease alters the way people think and act. Learning about psychology’s findings also changes people: They less often judge psychological disorders as moral failings, treatable by punishment and ostracism. They less often regard and treat women as men’s mental inferiors. They less often view and raise children as ignorant, willful beasts in need of taming. “In each case,” noted Morton Hunt (1990, p. 206), “knowledge has modified attitudes, and, through them, behavior.” Once aware of psychology’s well-

But bear in mind psychology’s limits. Don’t expect it to answer the ultimate questions, such as those posed by Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy (1904): “Why should I live? Why should I do anything? Is there in life any purpose which the inevitable death that awaits me does not undo and destroy?”

“Once expanded to the dimensions of a larger idea, [the mind] never returns to its original size.”

Oliver Wendell Holmes, 1809–1894

Although many of life’s significant questions are beyond psychology, some very important ones are illuminated by even a first psychology course. Through painstaking research, psychologists have gained insights into brain and mind, dreams and memories, depression and joy. Even the unanswered questions can renew our sense of mystery about things we do not yet understand. Moreover, your study of psychology can help teach you how to ask and answer important questions—

“I have uttered what I did not understand, things too wonderful for me.”

Job 42:3

Psychology deepens our appreciation for how we humans perceive, think, feel, and act. By so doing it can indeed enrich our lives and enlarge our vision. Through this book we hope to help guide you toward that end. As educator Charles Eliot said a century ago: “Books are the quietest and most constant of friends, and the most patient of teachers.”

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Match the specialty on the left with the description on the right.

| 1. Clinical psychology | a. Works to create social and physical environments that are healthy for all. |

| 2. Psychiatry | b. Studies, assesses, and treats people with psychological disorders but usually does not provide medical therapy. |

| 3. Community psychology | c. Branch of medicine dealing with psychological disorders. |

1. b, 2. c, 3. a

Improve Your Retention—and Your Grades

1-

Do you, like most students, assume that the way to cement your new learning is to reread? What helps even more—

As you will see in other modules, to master information you must actively process it. Your mind is not like your stomach, something to be filled passively; it is more like a muscle that grows stronger with exercise. Countless experiments reveal that people learn and remember best when they put material in their own words, rehearse it, and then retrieve and review it again.

The SQ3R study method incorporates these principles (McDaniel et al., 2009; Robinson, 1970). SQ3R is an acronym for its five steps: Survey, Question, Read, Retrieve,2 Review.

To study a module, first survey, taking a bird’s-

Before you read each main section, try to answer its numbered Learning Objective Question (for this section: “How can psychological principles help you learn and remember?”). Roediger and Bridgid Finn (2009) have found that “trying and failing to retrieve the answer is actually helpful to learning.” Those who test their understanding before reading, and discover what they don’t yet know, will learn and remember better.

Then read, actively searching for the answer to the question. At each sitting, read only as much of the module (usually a single main section) as you can absorb without tiring. Read actively and critically. Ask questions. Take notes. Make the ideas your own: How does what you’ve read relate to your own life? Does it support or challenge your assumptions? How convincing is the evidence?

Having read a section, retrieve its main ideas. “Active retrieval promotes meaningful learning,” says Karpicke (2012). So test yourself. This will not only help you figure out what you know, the testing itself will help you learn and retain the information more effectively. Even better, test yourself repeatedly. To facilitate this, we offer periodic Retrieval Practice opportunities throughout each module (see, for example, the questions in this module). After answering these questions for yourself, you can check the answers provided, and reread as needed.

“It pays better to wait and recollect by an effort from within, than to look at the book again.”

William James, Principles of Psychology, 1890

Finally, review: Read over any notes you have taken, again with an eye on the module’s organization, and quickly review the whole module. Write or say what a concept is before rereading to check your understanding.

Survey, question, read, retrieve, review. I have organized this book’s modules to facilitate your use of the SQ3R study system. Each module begins with an outline that aids your survey. Headings and Learning Objective Questions suggest issues and concepts you should consider as you read. The material is organized into sections of readable length. The Retrieval Practice questions will challenge you to retrieve what you have learned, and thus better remember it. The end-

Four additional study tips may further boost your learning:

Distribute your study time. One of psychology’s oldest findings is that spaced practice promotes better retention than massed practice. You’ll remember material better if you space your time over several study periods—

Spacing your study sessions requires a disciplined approach to managing your time. (Richard O. Straub explains time management in a helpful preface at the beginning of this text.)

Learn to think critically. Whether you are reading or in class, note people’s assumptions and values. What perspective or bias underlies an argument? Evaluate evidence. Is it anecdotal? Or is it based on informative experiments? Assess conclusions. Are there alternative explanations?

Process class information actively. Listen for the main ideas and sub-

Overlearn. Psychology tells us that overlearning improves retention. We are prone to overestimating how much we know. You may understand a module as you read it, but that feeling of familiarity can be deceptively comforting. Using the Retrieval Practice questions as well as LaunchPad’s varied opportunities, devote extra study time to testing your knowledge and exploring psychology.

Memory experts Elizabeth Bjork and Robert Bjork (2011) offer the bottom line for how to improve your retention and your grades:

Spend less time on the input side and more time on the output side, such as summarizing what you have read from memory or getting together with friends and asking each other questions. Any activities that involve testing yourself—

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- The __________ __________ describes the enhanced memory that results from repeated retrieval (as in self-testing) rather than from simple rereading of new information.

testing effect

- What does the acronym SQ3R stand for?

Survey, Question, Read, Retrieve, and Review