A.1 Personnel Psychology

Personnel Psychology

Personnel Psychology

A-

Psychologists can assist organizations at various stages of selecting and assessing employees. They may help identify needed job skills, decide upon selection methods, recruit and evaluate applicants, introduce and train new employees, and appraise their performance.

Matching Interests to Work

“So what interests you?” we may ask a new acquaintance. When faculty advisers or vocational counselors probe further, we may ask: “What do you love to do? What are you doing when time just flies—

A career counseling science aims, first, to assess people’s differing values, personalities, and, especially, interests, which are remarkably stable (Dik & Rottinghaus, 2013). (Your job may change, but your interests today will likely still be your interests in 10 years.) Second, it aims to alert people to well-

Harnessing Strengths

As a new AT&T human resources executive, psychologist Mary Tenopyr (1997) was assigned to solve a problem: Customer-

- She asked new applicants to respond to various test questions (without as yet making any use of their responses).

- She followed up later to assess which of the applicants excelled on the job.

- She identified the earlier test questions that best predicted success.

The happy result of her data-

Your strengths are any enduring qualities that can be productively applied. Are you naturally curious? Persuasive? Charming? Persistent? Competitive? Analytical? Empathic? Organized? Articulate? Neat? Mechanical? Any such trait, if matched with suitable work, can function as a strength (Buckingham, 2007).

Gallup researchers Marcus Buckingham and Donald Clifton (2001) have argued that the first step to a stronger organization is instituting a strengths-

An example: If you needed to hire new people in software development, and you had discovered that your best software developers are analytical, disciplined, and eager to learn, you would focus employment ads less on experience than on the identified strengths. Thus “Do you take a logical and systematic approach to problem solving [analytical]? Are you a perfectionist who strives for timely completion of your projects [disciplined]? Do you want to master Java, C++, and PHP [eager to learn]? If you can say Yes to these questions, then please call …”

Identifying people’s strengths and matching those strengths to work is a first step toward workplace effectiveness. To assess applicants’ strengths and decide who is best suited to the job, personnel managers use various tools (Sackett & Lievens, 2008), including ability tests, personality tests, and behavioral observations in “assessment centers” that test applicants on tasks that mimic the job they seek.

Discovering Your Strengths

You can use some of the techniques personnel psychologists have developed to identify your own strengths and pinpoint types of work that will likely prove satisfying and successful. Buckingham and Clifton (2001) have suggested asking yourself these questions:

- What activities give me pleasure? Bringing order out of chaos? Playing host? Helping others? Challenging sloppy thinking?

- What activities leave me wondering, “When can I do this again?” rather than, “When will this be over?”

- What sorts of challenges do I relish? And which do I dread?

- What sorts of tasks do I learn easily? And which do I struggle with?

Some people find themselves in flow—

The U.S. Department of Labor also offers a vocational interest questionnaire via its Occupational Information Network (O*NET). At www.mynextmove.org/explore/ip you will need about 10 minutes to respond to 60 items, indicating how much you would like or dislike activities ranging from building kitchen cabinets to playing a musical instrument. You will then receive feedback on how strongly your responses reflect six interest types specified by vocational psychologist John L. Holland (1996): realistic (hands-

Satisfied and successful people devote far less time to correcting their deficiencies than to accentuating their strengths. Top performers are “rarely well rounded,” Buckingham and Clifton found (p. 26). Instead, they have sharpened their existing skills. Given the persistence of our traits and temperaments, we should focus not on our deficiencies, but rather on identifying and employing our talents. There may be limits to the benefits of assertiveness training if you are extremely shy, of public speaking courses if you tend to be nervous and soft-

Identifying your talents can help you recognize the activities you learn quickly and find absorbing. Knowing your strengths, you can develop them further.

Do Interviews Predict Performance?

“Interviews are a terrible predictor of performance.”

Laszlo Bock, Google’s Vice President, People Operations, 2007

Most interviewers feel confident of their ability to predict long-

Unstructured Interviews and the Interviewer Illusion

Traditional unstructured interviews can provide a sense of someone’s personality—

- Interviewers presume that people are what they seem to be in the interview situation. An unstructured interview may create a false impression of a person’s behavior toward others in different situations. As personality psychologists explain, when meeting others, we discount the enormous influence of varying situations and mistakenly presume that what we see is what we will get. But research on everything from chattiness to conscientiousness reveals that how we behave reflects not only our enduring traits, but also the details of the particular situation (such as wanting to impress in a job interview).

- Interviewers’ preconceptions and moods color how they perceive interviewees’ responses (Cable & Gilovich, 1998; Macan & Dipboye, 1994). If interviewers instantly like a person who perhaps is similar to themselves, they may interpret the person’s assertiveness as indicating “confidence” rather than “arrogance.” If told certain applicants have been prescreened, interviewers are disposed to judge them more favorably.

- Interviewers judge people relative to those interviewed just before and after them (Simonsohn & Gino, 2013). If you are being interviewed for business or medical school, hope for a time when the other interviewees have been weak.

- Interviewers more often follow the successful careers of those they have hired than the successful careers of those they have rejected. This missing feedback prevents interviewers from getting a reality check on their hiring ability.

“Between the idea and reality … falls the shadow.”

T. S. Eliot, The Hollow Men, 1925

- Interviews disclose the interviewee’s good intentions, which are less revealing than habitual behaviors (Ouellette & Wood, 1998). Intentions matter. People can change. But the best predictor of the person we will be is the person we have been. Compared with work-avoiding university students, those who engage in their tasks are more likely, a decade and more later, to be engaged workers (Salmela-Aro et al., 2009). Educational attainments predict job performance partly because people who have shown up for school each day and done their tasks also tend to show up for work and do their tasks (Ng & Feldman, 2009). Wherever we go, we take ourselves along.

Hoping to improve prediction and selection, personnel psychologists have put people in simulated work situations, sought information on past performance, aggregated evaluations from multiple interviews, administered tests, and developed job-

Structured Interviews

Unlike casual conversation aimed at getting a feel for someone, structured interviews offer a disciplined method of collecting information. A personnel psychologist may analyze a job, script questions, and train interviewers. The interviewers then put the same questions, in the same order, to all applicants, and rate each applicant on established scales.

In an unstructured interview, someone might ask, “How organized are you?” “How well do you get along with people?” or “How do you handle stress?” Street-

By contrast, structured interviews pinpoint strengths (attitudes, behaviors, knowledge, and skills) that distinguish high performers in a particular line of work. The process includes outlining job-

To reduce memory distortions and bias, the interviewer takes notes and makes ratings as the interview proceeds and avoids irrelevant and follow-

A review of 150 findings revealed that structured interviews had double the predictive accuracy of unstructured seat-

If, instead, we let our intuitions bias the hiring process, noted Malcolm Gladwell (2000, p. 86), then “all we will have done is replace the old-

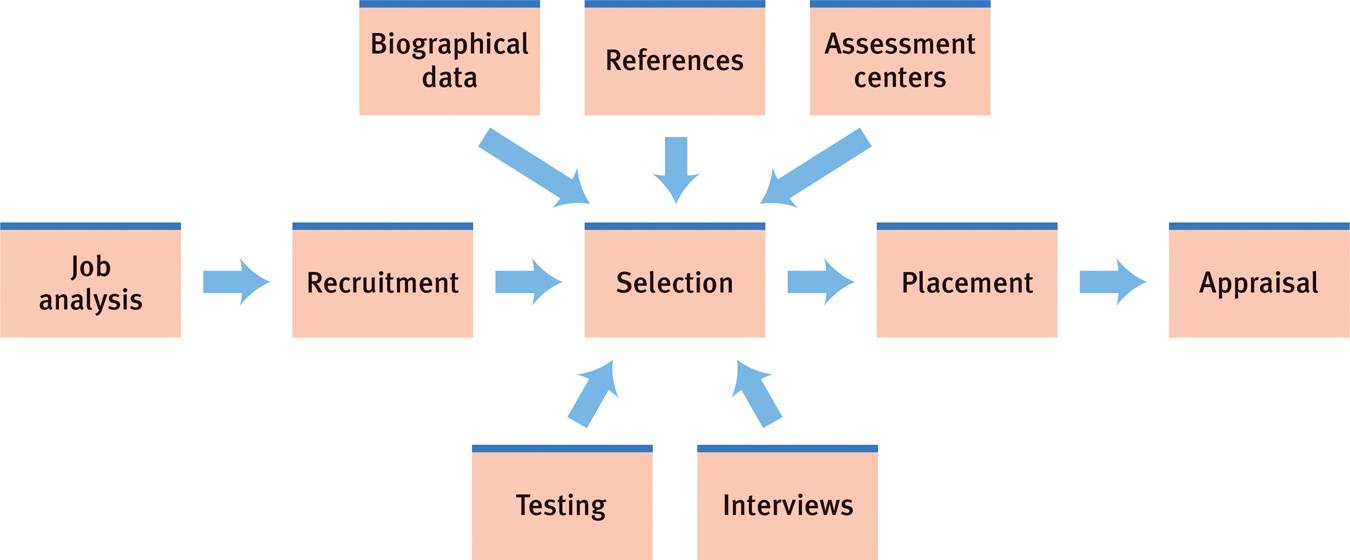

To recap, personnel psychologists assist organizations in analyzing jobs, recruiting well-

Figure A.1

Figure A.1Personnel psychologists’ tasks Personnel psychologists consult in human resources activities, from job definition to employee appraisal.

Appraising Performance

Performance appraisal serves organizational purposes: It helps decide who to retain, how to appropriately reward and pay people, and how to better harness employee strengths, sometimes with job shifts or promotions. Performance appraisal also serves individual purposes: Feedback affirms workers’ strengths and helps motivate needed improvements.

Performance appraisal methods include

- checklists on which supervisors simply check specific behaviors that describe the worker (“always attends to customers’ needs,” “takes long breaks”).

- graphic rating scales on which a supervisor checks, perhaps on a five-point scale, how often a worker is dependable, productive, and so forth.

- behavior rating scales on which a supervisor checks scaled behaviors that describe a worker’s performance. If rating the extent to which a worker “follows procedures,” the supervisor might mark the employee somewhere between “often takes shortcuts” and “always follows established procedures” (Levy, 2003).

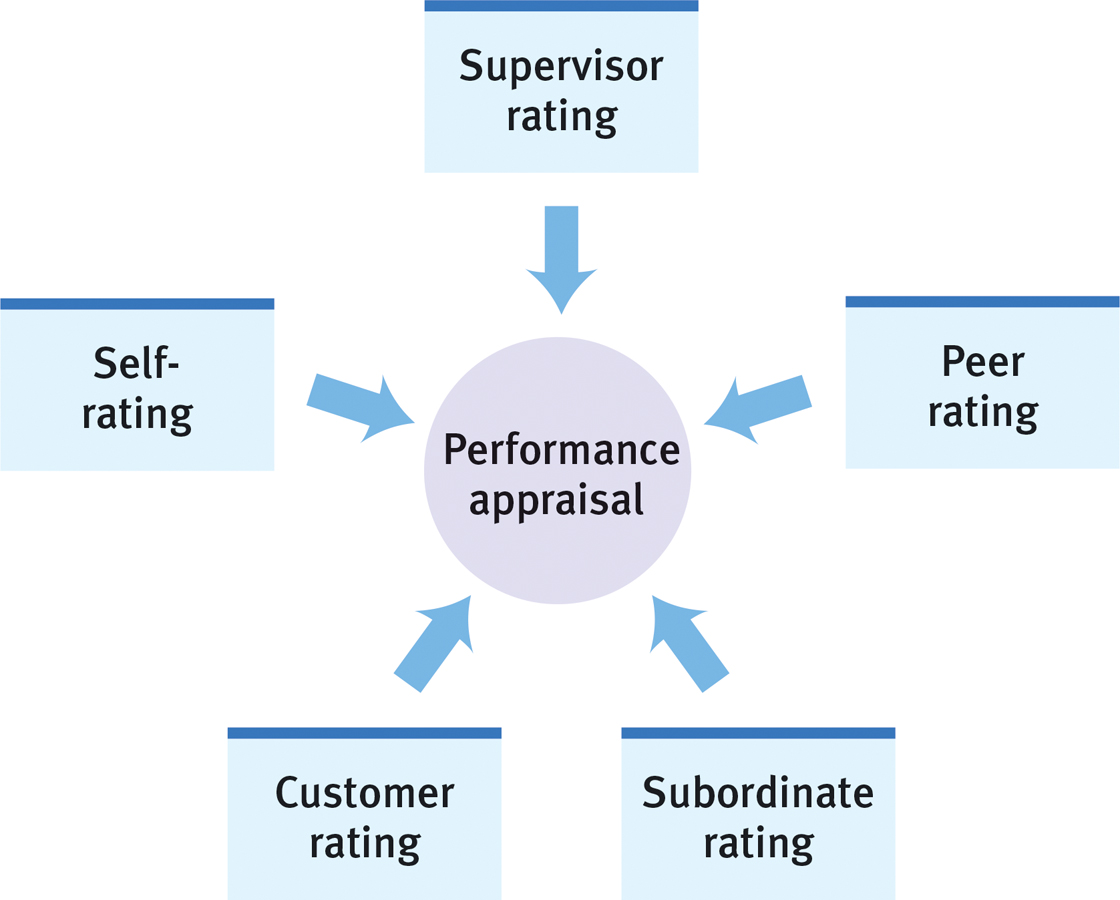

In some organizations, performance feedback comes not only from supervisors but also from all organizational levels. If you join an organization that practices 360-

Figure A.2

Figure A.2360-

Performance appraisal, like other social judgments, is vulnerable to bias (Murphy & Cleveland, 1995). Halo errors occur when one’s overall evaluation of an employee, or of a personal trait such as their friendliness, biases ratings of their specific work-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- A human resources director explains to you that “I don’t bother with tests or references. It’s all about the interview.” Based on I/O research, what concerns does this raise?

(1) Interviewers may presume people are what they seem to be in interviews. (2) Interviewers’ preconceptions and moods color how they perceive interviewees’ responses. (3) Interviewers judge people relative to other recent interviewees. (4) Interviewers tend to track the successful careers of those they hire, not the successful careers of those they reject. (5) Interviews tend to disclose prospective workers’ good intentions, not their habitual behaviors.