21.1 How Do We Learn?

21-

Psychologists define learning as the process of acquiring new and relatively enduring information or behaviors. By learning, we humans are able to adapt to our environments. We learn to expect and prepare for significant events such as food or pain (classical conditioning). We typically learn to repeat acts that bring rewards and avoid acts that bring unwanted results (operant conditioning). We learn new behaviors by observing events and watching others, and through language, we learn things we have neither experienced nor observed (cognitive learning). But how do we learn?

More than 200 years ago, philosophers John Locke and David Hume echoed Aristotle’s conclusion from 2000 years earlier: We learn by association. Our minds naturally connect events that occur in sequence. Suppose you see and smell freshly baked bread, eat some, and find it satisfying. The next time you see and smell fresh bread, you will expect that eating it will again be satisfying. So, too, with sounds. If you associate a sound with a frightening consequence, hearing the sound alone may trigger your fear. As one 4-

Learned associations often operate subtly:

- Give people a red pen (associated with error marking) rather than a black pen and, when correcting essays, they will spot more errors and give lower grades (Rutchick et al., 2010).

- When voting, people are more likely to support taxes to aid education if their assigned voting place is in a school (Berger et al., 2008). In the conservative American South, voters are more likely to support a same-sex marriage ban when voting in a church (Rutchick, 2010).

- After handling dirty paper money, people (market vendors, students in laboratory games) become more selfish and exploitative; after handling fresh, clean money they become more unselfish and fair (Yang et al., 2013).

Learned associations also feed our habitual behaviors (Wood et al., 2014). As we repeat behaviors in a given context—

How long does it take to form such habits? To find out, one British research team asked 96 university students to choose some healthy behavior (such as running before dinner or eating fruit with lunch), to do it daily for 84 days, and to record whether the behavior felt automatic (something they did without thinking and would find it hard not to do). On average, behaviors became habitual after about 66 days (Lally et al., 2010). Is there something you’d like to make a routine part of your life? Just do it every day for two months, or a bit longer for exercise, and you likely will find yourself with a new habit.

Other animals also learn by association. Disturbed by a squirt of water, the sea slug Aplysia protectively withdraws its gill. If the squirts continue, as happens naturally in choppy water, the withdrawal response diminishes. But if the sea slug repeatedly receives an electric shock just after being squirted, its response to the squirt instead grows stronger. The animal has associated the squirt with the impending shock.

Complex animals can learn to associate their own behavior with its outcomes. An aquarium seal will repeat behaviors, such as slapping and barking, that prompt people to toss it a herring.

Most of us would be unable to name the order of the songs on our favorite album or playlist. Yet, hearing the end of one piece cues (by association) an anticipation of the next. Likewise, when singing your national anthem, you associate the end of each line with the beginning of the next. (Pick a line out of the middle and notice how much harder it is to recall the previous line.)

By linking two events that occur close together, both animals are exhibiting associative learning. The sea slug associates the squirt with an impending shock; the seal associates slapping and barking with a herring treat. Each animal has learned something important to its survival: anticipating the immediate future.

This process of learning associations is conditioning. It takes two main forms:

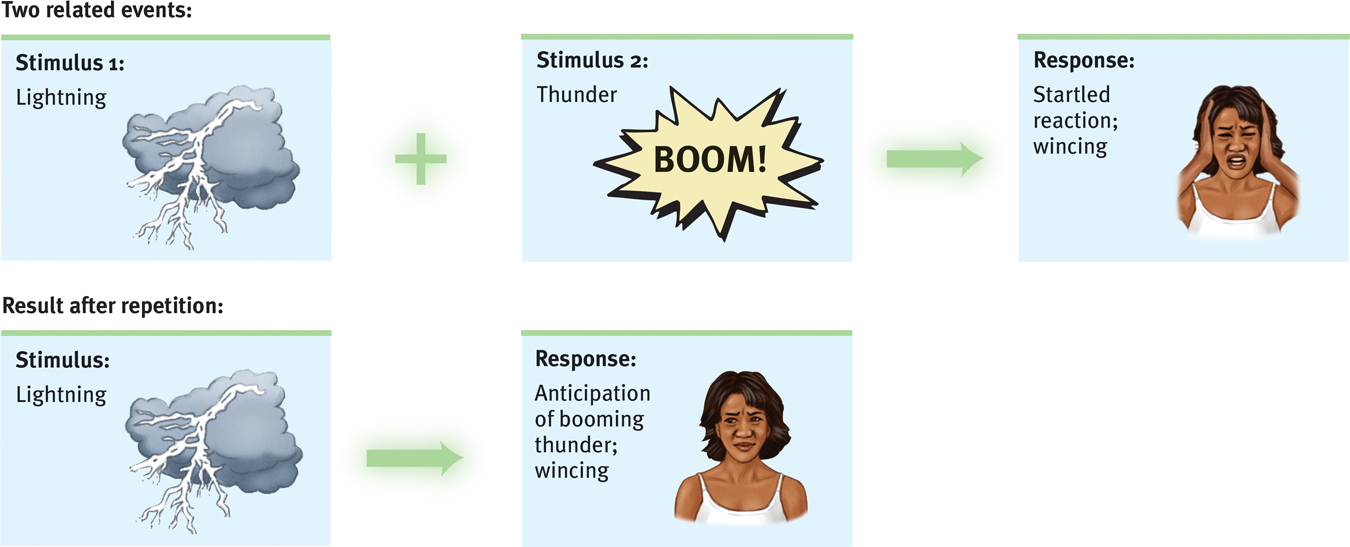

- In classical conditioning, we learn to associate two stimuli and thus to anticipate events. (A stimulus is any event or situation that evokes a response.) We learn that a flash of lightning signals an impending crack of thunder; when lightning flashes nearby, we start to brace ourselves (FIGURE 21.1). We associate stimuli that we do not control, and we respond automatically, which is called respondent behavior.

Figure 21.1

Figure 21.1

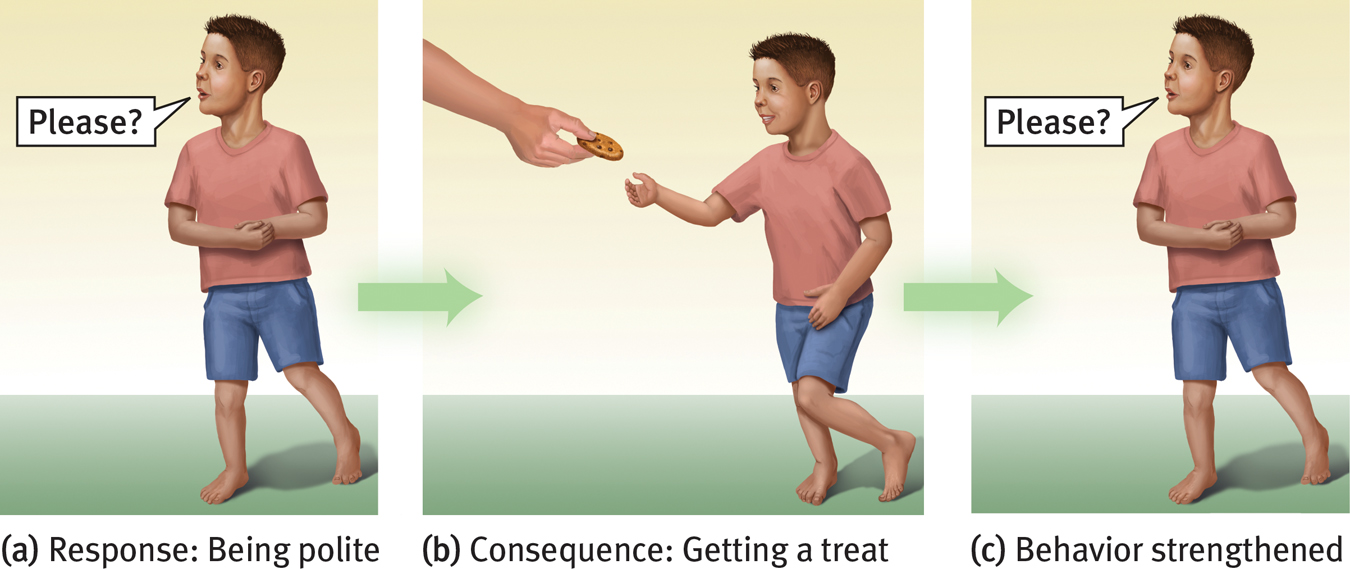

Classical conditioning - In operant conditioning, we learn to associate a response (our behavior) and its consequence. Thus we (and other animals) learn to repeat acts followed by good results (FIGURE 21.2) and avoid acts followed by bad results. These associations produce operant behaviors.

Figure 21.2

Figure 21.2

Operant conditioning

To simplify, we will explore these two types of associative learning separately. Often, though, they occur together, as on one Japanese cattle ranch, where the clever rancher outfits his herd with electronic pagers which he calls from his cell phone. After a week of training, the animals learn to associate two stimuli—

Conditioning is not the only form of learning. Through cognitive learning, we acquire mental information that guides our behavior. Observational learning, one form of cognitive learning, lets us learn from others’ experiences. Chimpanzees, for example, sometimes learn behaviors merely by watching others perform them. If one animal sees another solve a puzzle and gain a food reward, the observer may perform the trick more quickly. So, too, in humans: We look and we learn.

Let’s look more closely now at classical conditioning.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Why are habits, such as having something sweet with that cup of coffee, so hard to break?

Habits form when we repeat behaviors in a given context and, as a result, learn associations—