21.2 Classical Conditioning

21-

For many people, the name Ivan Pavlov (1849–

Pavlov’s work laid the foundation for many of psychologist John B. Watson’s ideas. In searching for laws underlying learning, Watson (1913) urged his colleagues to discard reference to inner thoughts, feelings, and motives. The science of psychology should instead study how organisms respond to stimuli in their environments, said Watson: “Its theoretical goal is the prediction and control of behavior. Introspection forms no essential part of its methods.” Simply said, psychology should be an objective science based on observable behavior.

This view, which Watson called behaviorism, influenced North American psychology during the first half of the twentieth century. Pavlov and Watson shared both a disdain for “mentalistic” concepts (such as consciousness) and a belief that the basic laws of learning were the same for all animals—

Pavlov’s Experiments

21-

Pavlov was driven by a lifelong passion for research. After setting aside his initial plan to follow his father into the Russian Orthodox priesthood, Pavlov received a medical degree at age 33 and spent the next two decades studying the digestive system. This work earned him Russia’s first Nobel Prize in 1904. But his novel experiments on learning, which consumed the last three decades of his life, earned this feisty scientist his place in history.

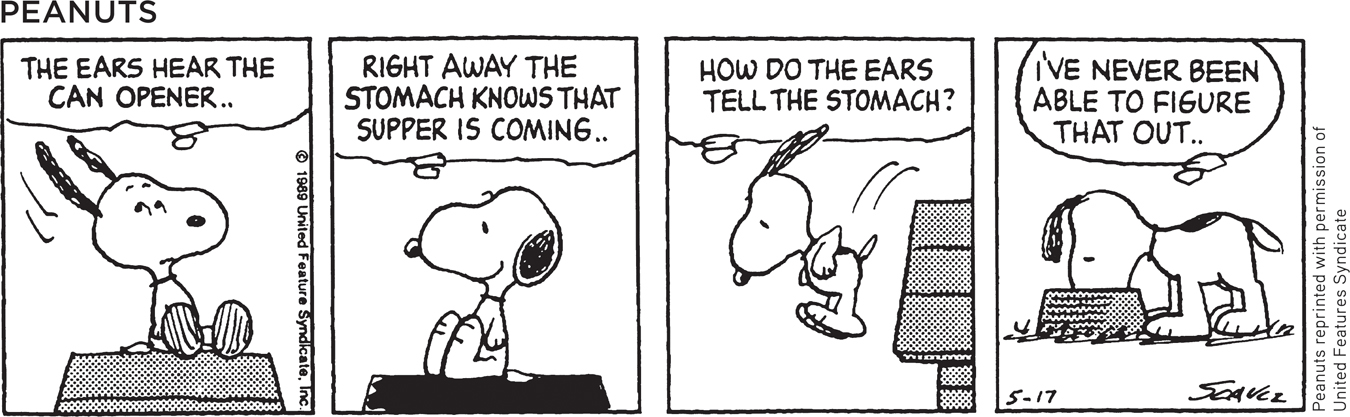

Pavlov’s new direction came when his creative mind seized on an incidental observation. Without fail, putting food in a dog’s mouth caused the animal to salivate. Moreover, the dog began salivating not only at the taste of the food, but also at the mere sight of the food, or the food dish, or the person delivering the food, or even at the sound of that person’s approaching footsteps. At first, Pavlov considered these “psychic secretions” an annoyance—

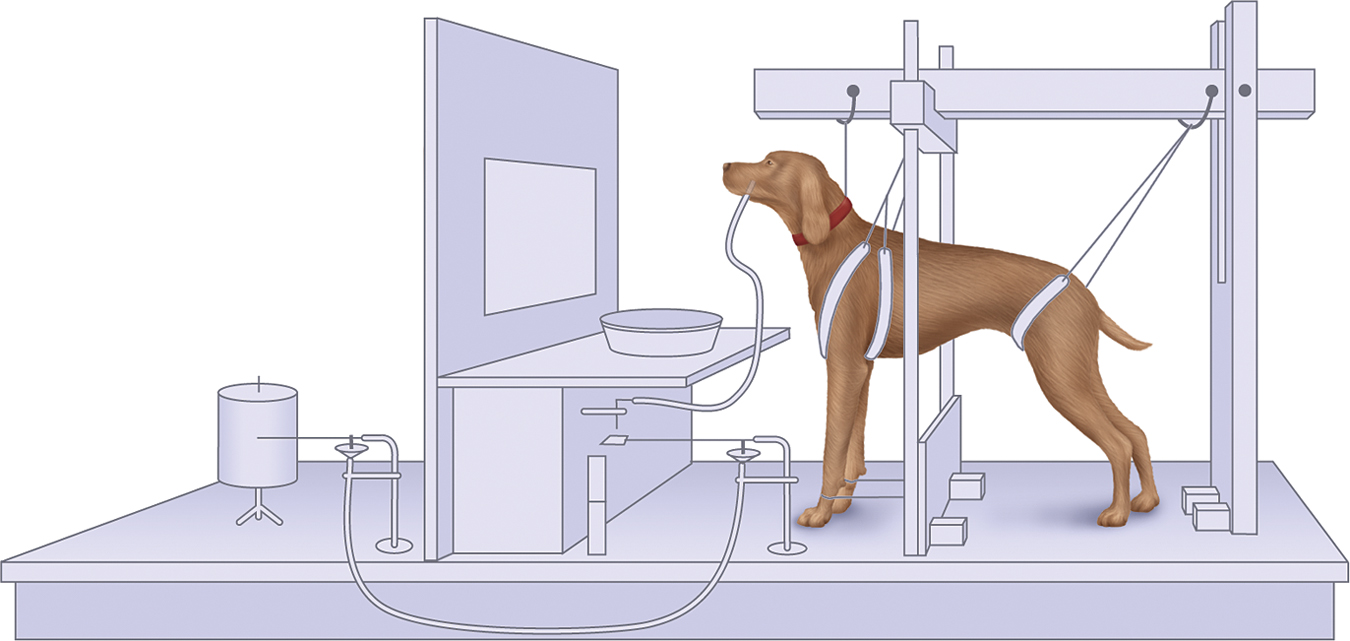

Pavlov and his assistants tried to imagine what the dog was thinking and feeling as it drooled in anticipation of the food. This only led them into fruitless debates. So, to explore the phenomenon more objectively, they experimented. To eliminate other possible influences, they isolated the dog in a small room, secured it in a harness, and attached a device to divert its saliva to a measuring instrument (FIGURE 21.3). From the next room, they presented food—

Figure 21.3

Figure 21.3Pavlov’s device for recording salivation A tube in the dog’s cheek collects saliva, which is measured in a cylinder outside the chamber.

The answers proved to be Yes and Yes. Just before placing food in the dog’s mouth to produce salivation, Pavlov sounded a tone. After several pairings of tone and food, the dog, now anticipating the meat powder, began salivating to the tone alone. In later experiments, a buzzer1, a light, a touch on the leg, even the sight of a circle set off the drooling. (This procedure works with people, too. When hungry young Londoners viewed abstract figures before smelling peanut butter or vanilla, their brain soon responded in anticipation to the abstract images alone [Gottfried et al., 2003].)

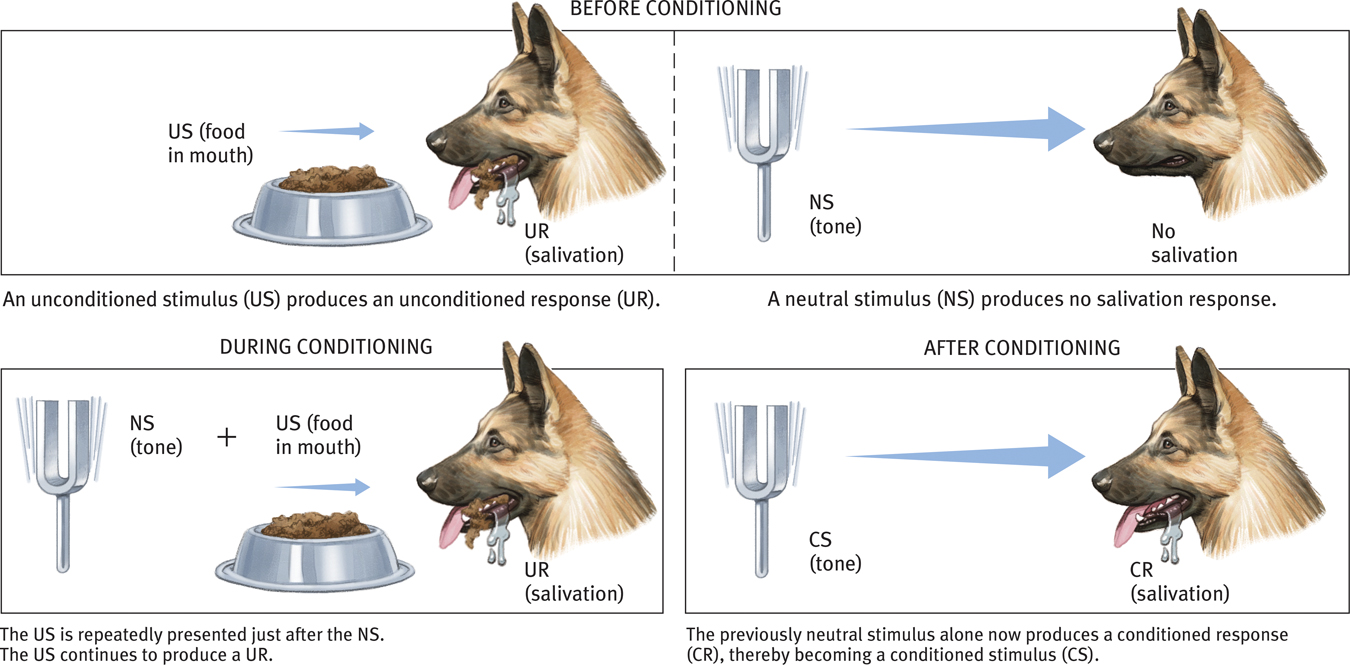

A dog does not learn to salivate in response to food in its mouth. Rather, food in the mouth automatically, unconditionally, triggers a dog’s salivary reflex (FIGURE 21.4). Thus, Pavlov called the drooling an unconditioned response (UR). And he called the food an unconditioned stimulus (US).

Figure 21.4

Figure 21.4Pavlov’s classic experiment Pavlov presented a neutral stimulus (a tone) just before an unconditioned stimulus (food in mouth). The neutral stimulus then became a conditioned stimulus, producing a conditioned response.

Salivation in response to the tone, however, is learned. It is conditional upon the dog’s associating the tone with the food. Thus, we call this response the conditioned response (CR). The stimulus that used to be neutral (in this case, a previously meaningless tone that now triggers salivation) is the conditioned stimulus (CS). Distinguishing these two kinds of stimuli and responses is easy: Conditioned = learned; unconditioned = unlearned.

If Pavlov’s demonstration of associative learning was so simple, what did he do for the next three decades? What discoveries did his research factory publish in his 532 papers on salivary conditioning (Windholz, 1997)? He and his associates explored five major conditioning processes: acquisition, extinction, spontaneous recovery, generalization, and discrimination.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- An experimenter sounds a tone just before delivering an air puff to your blinking eye. After several repetitions, you blink to the tone alone. What is the NS? The US? The UR? The CS? The CR?

NS = tone before conditioning; US = air puff; UR = blink to air puff; CS = tone after conditioning; CR = blink to tone.

Acquisition

21-

To understand the acquisition, or initial learning, of the stimulus-

What do you suppose would happen if the food (US) appeared before the tone (NS) rather than after? Would conditioning occur? Not likely. With but a few exceptions, conditioning doesn’t happen when the NS follows the US. Remember, classical conditioning is biologically adaptive because it helps humans and other animals prepare for good or bad events. To Pavlov’s dogs, the originally neutral tone became a CS after signaling an important biological event—

More recent research on male Japanese quail shows how a CS can signal another important biological event (Domjan, 1992, 1994, 2005). Just before presenting a sexually approachable female quail, the researchers turned on a red light. Over time, as the red light continued to herald the female’s arrival, the light caused the male quail to become excited. They developed a preference for their cage’s red-

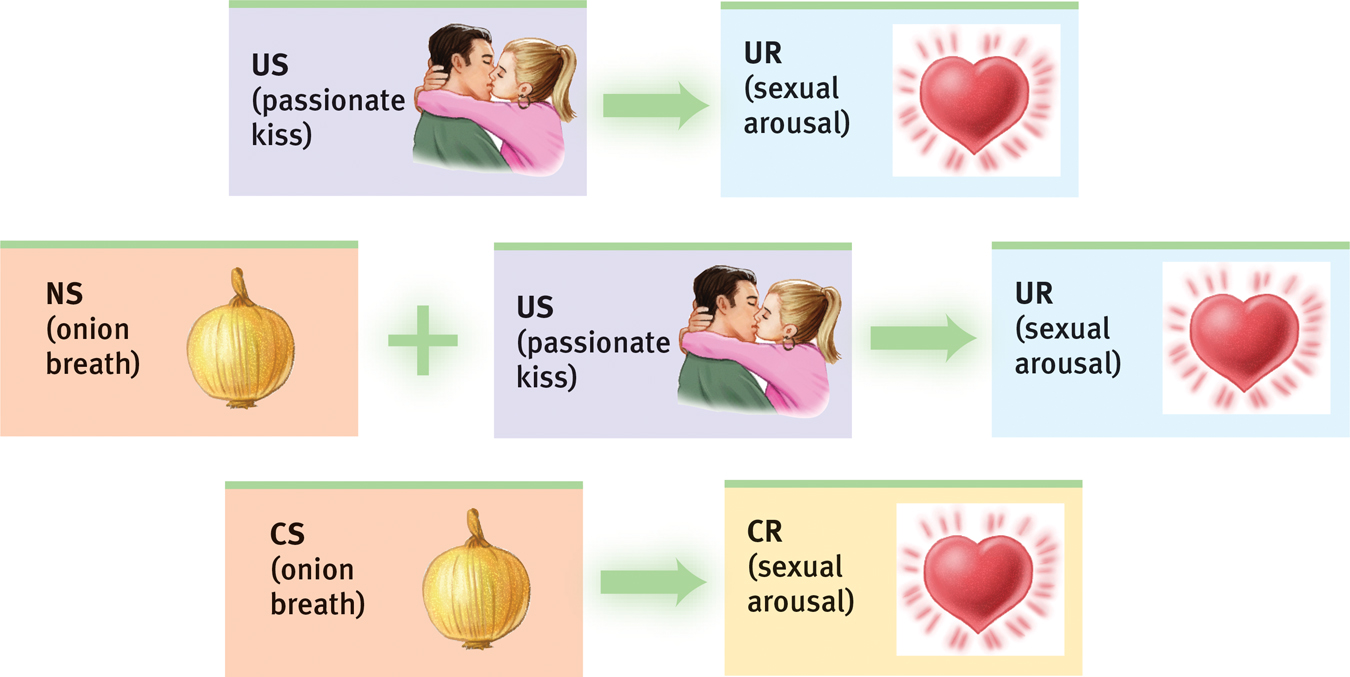

In humans, too, objects, smells, and sights associated with sexual pleasure—

Figure 21.5

Figure 21.5An unexpected CS Psychologist Michael Tirrell (1990) recalled: “My first girlfriend loved onions, so I came to associate onion breath with kissing. Before long, onion breath sent tingles up and down my spine. Oh what a feeling!”

Through higher-order conditioning, a new NS can become a new CS without the presence of a US. All that’s required is for it to become associated with a previously conditioned stimulus. If a tone regularly signals food and produces salivation, then a light that becomes associated with the tone may also begin to trigger salivation. Although this higher-

Remember:

NS = Neutral Stimulus

US = Unconditioned Stimulus

UR = Unconditioned Response

CS = Conditioned Stimulus

CR = Conditioned Response

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- If the aroma of a baking cake sets your mouth to watering, what is the US? The CS? The CR?

The cake (and its taste) are the US. The associated aroma is the CS. Salivation to the aroma is the CR.

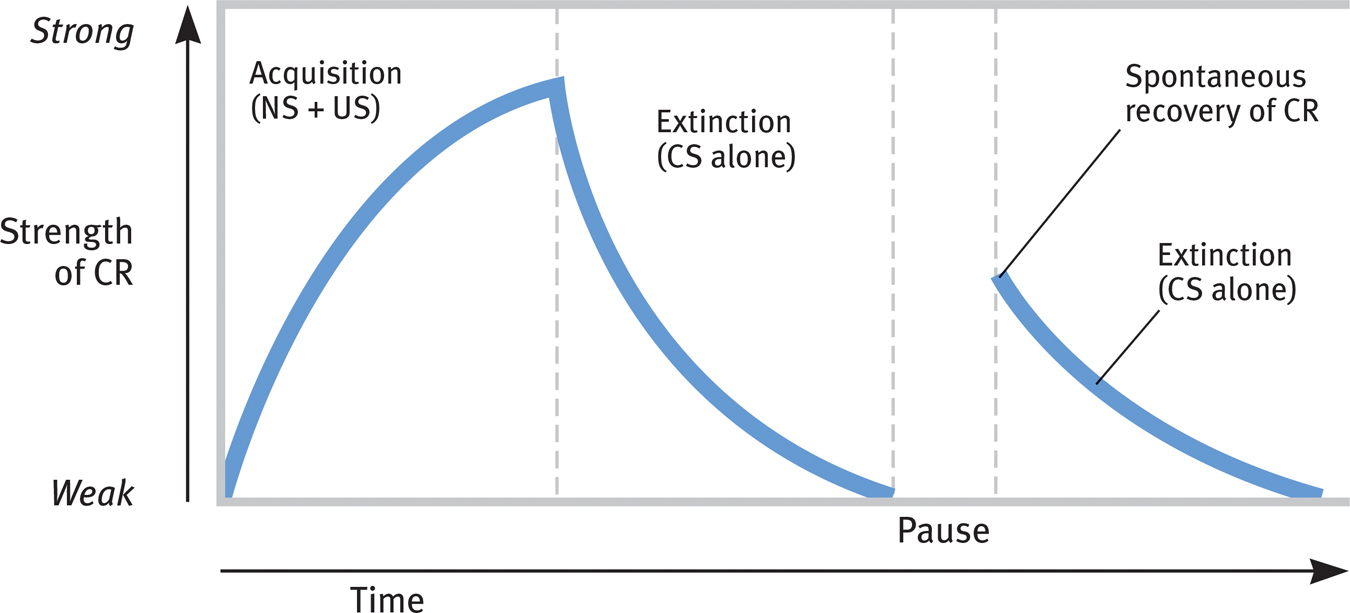

Extinction and Spontaneous RecoveryWhat would happen, Pavlov wondered, if after conditioning, the CS occurred repeatedly without the US? If the tone sounded again and again, but no food appeared, would the tone still trigger salivation? The answer was mixed. The dogs salivated less and less, a reaction known as extinction, which is the diminished response that occurs when the CS (tone) no longer signals an impending US (food). But a different picture emerged when Pavlov allowed several hours to elapse before sounding the tone again. After the delay, the dogs would again begin salivating to the tone (FIGURE 21.6). This spontaneous recovery—the reappearance of a (weakened) CR after a pause—

Figure 21.6

Figure 21.6Idealized curve of acquisition, extinction, and spontaneous recovery The rising curve shows the CR rapidly growing stronger as the NS becomes a CS due to repeated pairing with the US (acquisition). The CR then weakens rapidly as the CS is presented alone (extinction). After a pause, the (weakened) CR reappears (spontaneous recovery).

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- The first step of classical conditioning, when an NS becomes a CS, is called ______________. When a US no longer follows the CS, and the CR becomes weakened, this is called ______________.

acquisition, extinction

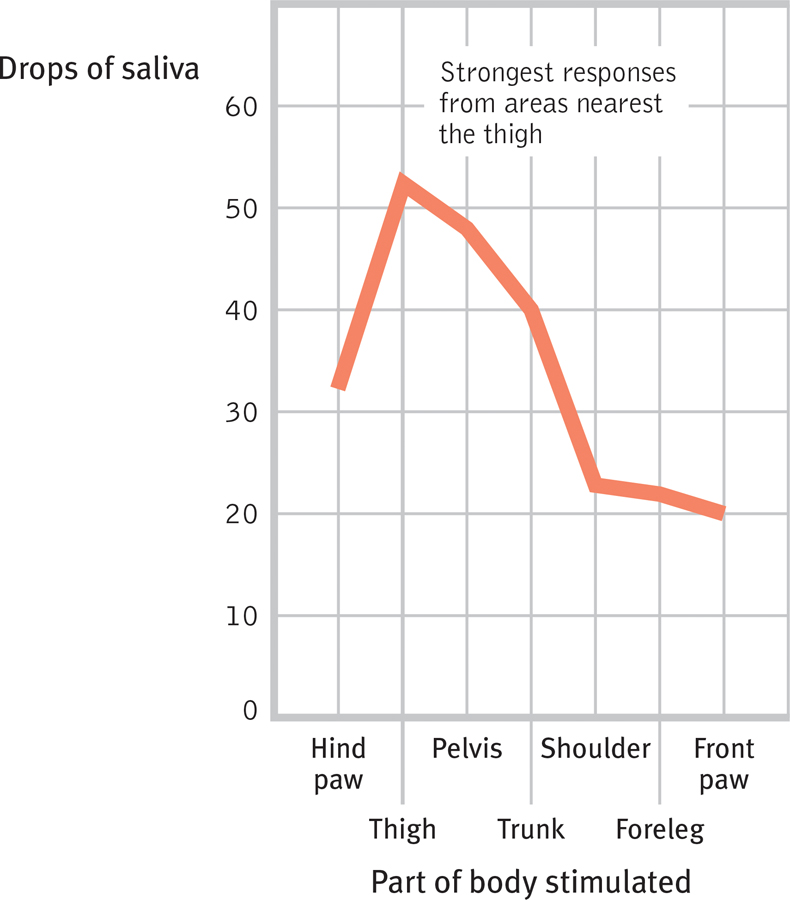

GeneralizationPavlov and his students noticed that a dog conditioned to the sound of one tone also responded somewhat to the sound of a new and different tone. Likewise, a dog conditioned to salivate when rubbed would also drool a bit when scratched (Windholz, 1989) or when touched on a different body part (FIGURE 21.7). This tendency to respond likewise to stimuli similar to the CS is called generalization.

Figure 21.7

Figure 21.7Generalization Pavlov demonstrated generalization by attaching miniature vibrators to various parts of a dog’s body. After conditioning salivation to stimulation of the thigh, he stimulated other areas. The closer a stimulated spot was to the dog’s thigh, the stronger the conditioned response. (Data from Pavlov, 1927.)

Generalization can be adaptive, as when toddlers taught to fear moving cars also become afraid of moving trucks and motorcycles. And generalized fears can linger. One Argentine writer who underwent torture still recoils with fear when he sees black shoes—

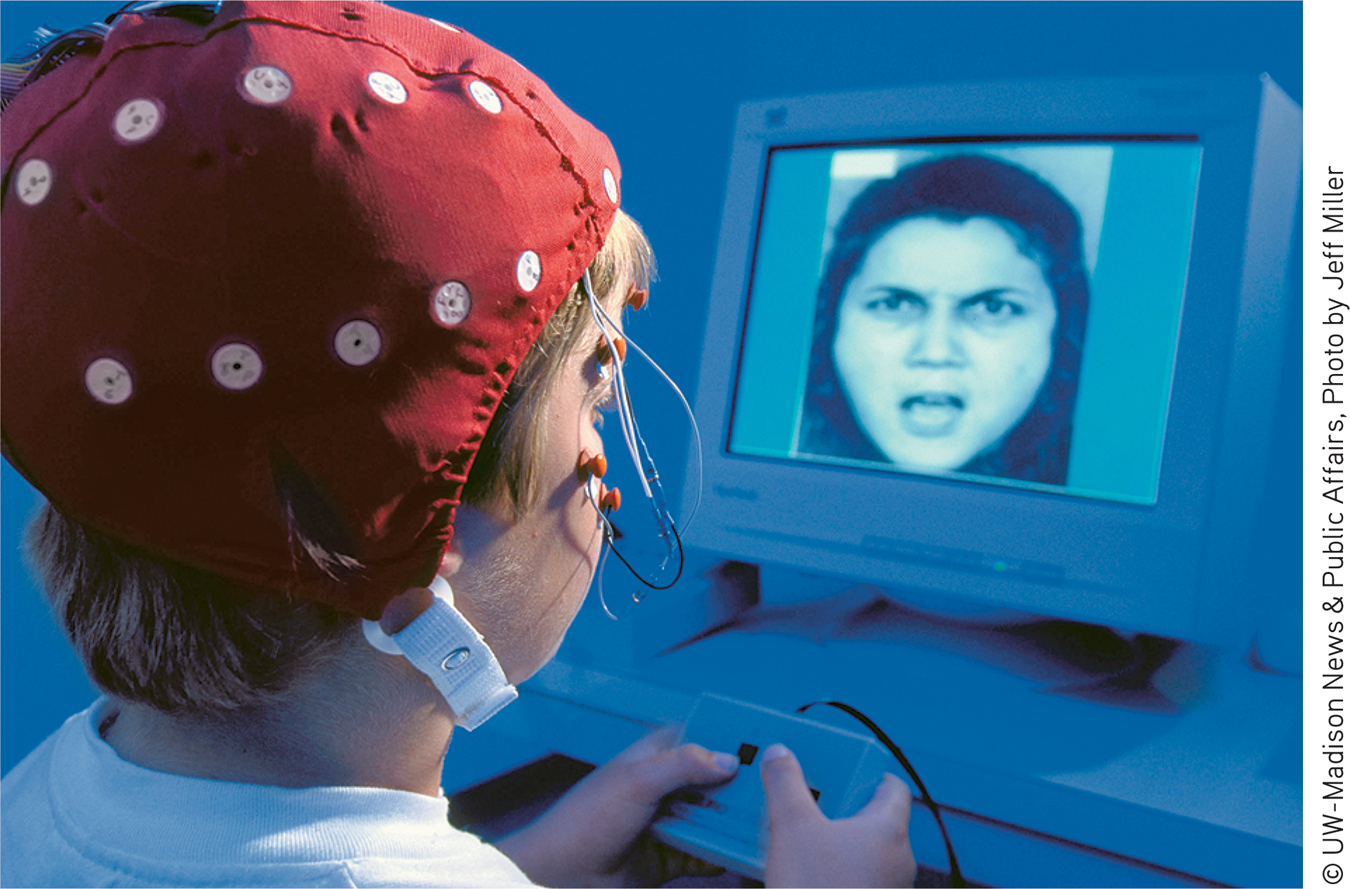

Figure 21.8

Figure 21.8Child abuse leaves tracks in the brain Abused children’s sensitized brains react more strongly to angry faces (Pollak et al., 1998). This generalized anxiety response may help explain their greater risk of psychological disorder.

Stimuli similar to naturally disgusting objects will, by association, also evoke some disgust, as otherwise desirable fudge does when shaped to resemble dog feces (Rozin et al., 1986). In each of these human examples, people’s emotional reactions to one stimulus have generalized to similar stimuli.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

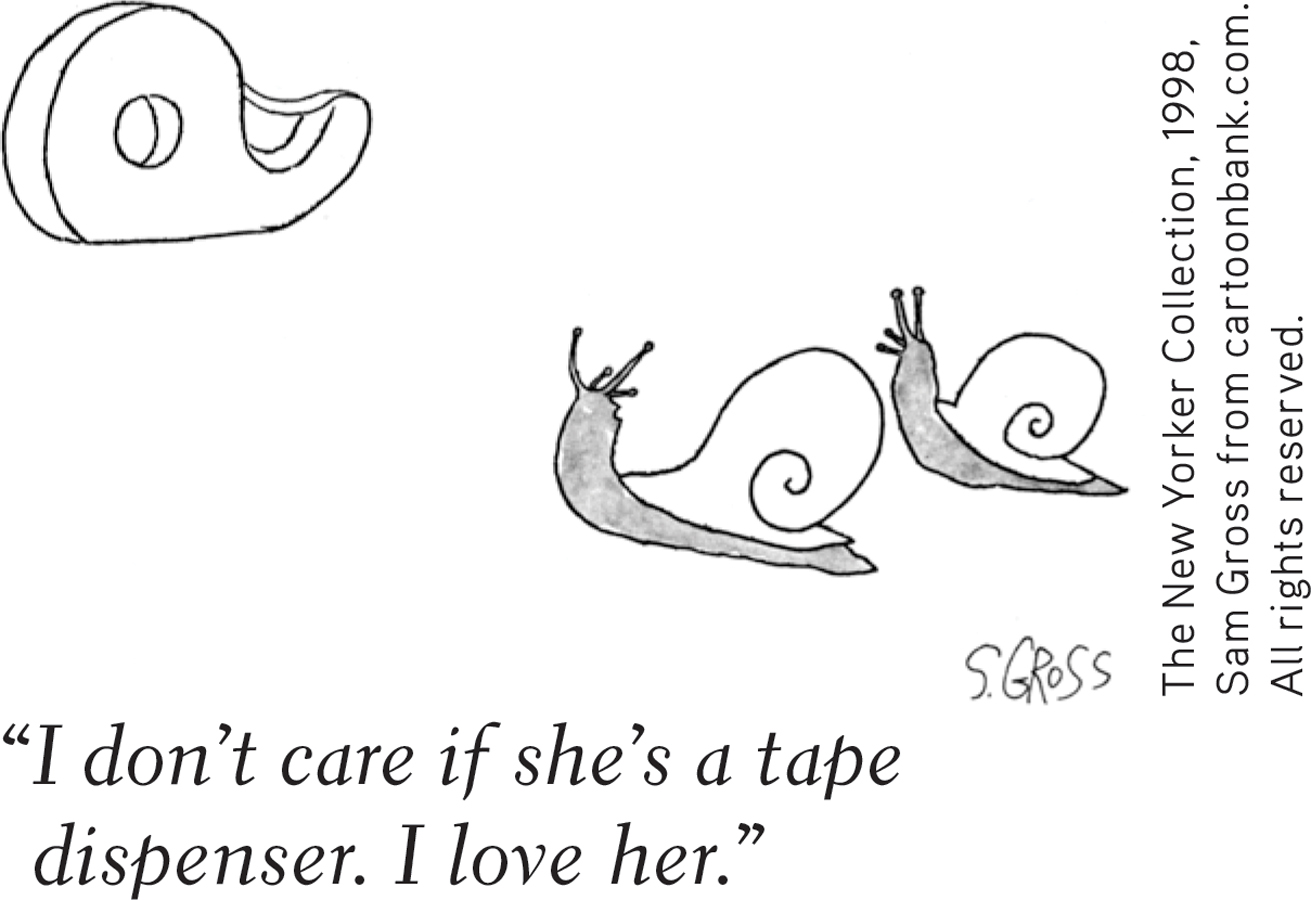

- What conditioning principle is influencing the snail’s affections?

Generalization

DiscriminationPavlov’s dogs also learned to respond to the sound of a particular tone and not to other tones. This learned ability to distinguish between a conditioned stimulus (which predicts the US) and other irrelevant stimuli is called discrimination. Being able to recognize differences is adaptive. Slightly different stimuli can be followed by vastly different consequences. Confronted by a guard dog, your heart may race; confronted by a guide dog, it probably will not.

Pavlov’s Legacy

21-

What remains today of Pavlov’s ideas? A great deal. Most psychologists now agree that classical conditioning is a basic form of learning. Judged with today’s knowledge of the interplay of our biology, psychology, and social-

Why does Pavlov’s work remain so important? If he had merely taught us that old dogs can learn new tricks, his experiments would long ago have been forgotten. Why should we care that dogs can be conditioned to salivate at the sound of a tone? The importance lies, first, in the finding that many other responses to many other stimuli can be classically conditioned in many other organisms—in fact, in every species tested, from earthworms to fish to dogs to monkeys to people (Schwartz, 1984). Thus, classical conditioning is one way that virtually all organisms learn to adapt to their environment.

Second, Pavlov showed us how a process such as learning can be studied objectively. He was proud that his methods involved virtually no subjective judgments or guesses about what went on in a dog’s mind. The salivary response is a behavior measurable in cubic centimeters of saliva. Pavlov’s success therefore suggested a scientific model for how the young discipline of psychology might proceed—

To review Pavlov’s classic work and to play the role of experimenter in classical conditioning research, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Classical Conditioning. See also a 3-minute re-creation of Pavlov’s lab in the Video: Pavlov’s Discovery of Classical Conditioning.

To review Pavlov’s classic work and to play the role of experimenter in classical conditioning research, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Classical Conditioning. See also a 3-minute re-creation of Pavlov’s lab in the Video: Pavlov’s Discovery of Classical Conditioning.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- In slasher movies, sexually arousing images of women are sometimes paired with violence against women. Based on classical conditioning principles, what might be an effect of this pairing?

If viewing an attractive nude or seminude woman (a US) elicits sexual arousal (a UR), then pairing the US with a new stimulus (violence) could turn the violence into a conditioned stimulus (CS) that also becomes sexually arousing, a conditioned response (CR).

Applications of Classical Conditioning

21-

In countless areas of psychology, including consciousness, motivation, emotion, health, psychological disorders, and therapy, Pavlov’s principles are now being used to influence human health and well-

- Former drug users often feel a craving when they are again in the drug-using context—with people or in places they associate with previous highs. Thus, drug counselors advise addicts to steer clear of people and settings that may trigger these cravings (Siegel, 2005).

- Classical conditioning even works on the body’s disease-fighting immune system. When a particular taste accompanies a drug that influences immune responses, the taste by itself may come to produce an immune response (Ader & Cohen, 1985).

Pavlov’s work also provided a basis for Watson’s (1913) idea that human emotions and behaviors, though biologically influenced, are mainly a bundle of conditioned responses. Working with an 11-

For years, people wondered what became of Little Albert. Sleuthing by Russell Powell and his colleagues (2014) found a well-

People also wondered what became of Watson. After losing his Johns Hopkins professorship over an affair with Raynor (his graduate student, whom he later married), he joined an advertising agency as the company’s resident psychologist. There, he used his knowledge of associative learning to conceive many successful advertising campaigns, including one for Maxwell House that helped make the “coffee break” an American custom (Hunt, 1993).

The treatment of Little Albert would be unacceptable by today’s ethical standards. Also, some psychologists had difficulty repeating Watson and Rayner’s findings with other children. Nevertheless, Little Albert’s learned fears led many psychologists to wonder whether each of us might be a walking repository of conditioned emotions. If so, might extinction procedures or even new conditioning help us change our unwanted responses to emotion-

One patient, who for 30 years had feared entering an elevator alone, did just that. Following his therapist’s advice, he forced himself to enter 20 elevators a day. Within 10 days, his fear had nearly vanished (Ellis & Becker, 1982). With support from airline AirTran, comedian-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- In Watson and Rayner’s experiments, “Little Albert” learned to fear a white rat after repeatedly experiencing a loud noise as the rat was presented. In this experiment, what was the US? The UR? The NS? The CS? The CR?

The US was the loud noise; the UR was the fear response to the noise; the NS was the rat before it was paired with the noise; the CS was the rat after pairing; the CR was fear of the rat.