22.2 Skinner's Legacy

22-

B. F. Skinner stirred a hornet’s nest with his outspoken beliefs. He repeatedly insisted that external influences, not internal thoughts and feelings, shape behavior. And he urged people to use operant principles to influence others’ behavior at school, work, and home. Knowing that behavior is shaped by its results, he argued that we should use rewards to evoke more desirable behavior.

Skinner’s critics objected, saying that he dehumanized people by neglecting their personal freedom and by seeking to control their actions. Skinner’s reply: External consequences already haphazardly control people’s behavior. Why not administer those consequences toward human betterment? Wouldn’t reinforcers be more humane than the punishments used in homes, schools, and prisons? And if it is humbling to think that our history has shaped us, doesn’t this very idea also give us hope that we can shape our future? In such ways, and through his ideas for positively reinforcing character strengths, Skinner actually anticipated some of today’s positive psychology (Adams, 2012).

To review and experience simulations of operant conditioning, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Operant Conditioning and also Shaping.

To review and experience simulations of operant conditioning, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Operant Conditioning and also Shaping.

Applications of Operant Conditioning

Psychologists are applying operant conditioning principles to help people with a variety of challenges, from moderating high blood pressure to gaining social skills. Reinforcement technologies are also at work in schools, sports, workplaces, and homes, and these principles can support our self-

At SchoolMore than 50 years ago, Skinner and others worked toward a day when "machines and textbooks" would shape learning in small steps, by immediately reinforcing correct responses. Such machines and textbooks, they said, would revolutionize education and free teachers to focus on each student's special needs. "Good instruction demands two things," said Skinner (1989). "Students must be told immediately whether what they do is right or wrong and, when right, they must be directed to the step to be taken next."

Skinner might be pleased to know that many of his ideals for education are now possible. Teachers used to find it difficult to pace material to each student's rate of learning, and to provide prompt feedback. Online adaptive quizzing, such as the LearningCurve system available with this text, does both. Students move through quizzes at their own pace, according to their own level of understanding. And they get immediate feedback on their efforts, including personalized study plans.

In SportsThe key to shaping behavior in athletic performance, as elsewhere, is first reinforcing small successes and then gradually increasing the challenge. Golf students can learn putting by starting with very short putts, and then, as they build mastery, stepping back farther and farther. Novice batters can begin with half swings at an oversized ball pitched from 10 feet away, giving them the immediate pleasure of smacking the ball. As the hitters’ confidence builds with their success and they achieve mastery at each level, the pitcher gradually moves back—

At WorkKnowing that reinforcers influence productivity, many organizations have invited employees to share the risks and rewards of company ownership. Others focus on reinforcing a job well done. Rewards are most likely to increase productivity if the desired performance has been well defined and is achievable. The message for managers? Reward specific, achievable behaviors, not vaguely defined “merit.”

Operant conditioning also reminds us that reinforcement should be immediate. IBM legend Thomas Watson understood this. When he observed an achievement, he wrote the employee a check on the spot (Peters & Waterman, 1982). But rewards need not be material, or lavish. An effective manager may simply walk the floor and sincerely affirm people for good work, or write notes of appreciation for a completed project. As Skinner said, “How much richer would the whole world be if the reinforcers in daily life were more effectively contingent on productive work?”

At HomeAs we have seen, parents can learn from operant conditioning practices. Parent-

To disrupt this cycle, parents should remember that basic rule of shaping: Notice people doing something right and affirm them for it. Give children attention and other reinforcers when they are behaving well. Target a specific behavior, reward it, and watch it increase. When children misbehave or are defiant, don’t yell at them or hit them. Simply explain the misbehavior and give them a time-

Conditioning principles may also be applied in clinical settings. Explore some of these applications in LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If People Can Learn to Reduce Anxiety?

Finally, we can use operant conditioning in our own lives. To reinforce your own desired behaviors (perhaps to improve your study habits) and extinguish the undesired ones (to stop smoking, for example), psychologists suggest taking these steps:

- State a realistic goal in measurable terms. You might, for example, aim to boost your study time by an hour a day.

- Decide how, when, and where you will work toward your goal. Take time to plan. Those who specify how they will implement goals more often fulfill them (Gollwitzer & Oettingen, 2012).

- Monitor how often you engage in your desired behavior. You might log your current study time, noting under what conditions you do and don’t study. (When I [DM] began writing textbooks, I logged how I spent my time each day and was amazed to discover how much time I was wasting. I [ND] experienced a similar rude awakening when I started tracking my daily writing hours.)

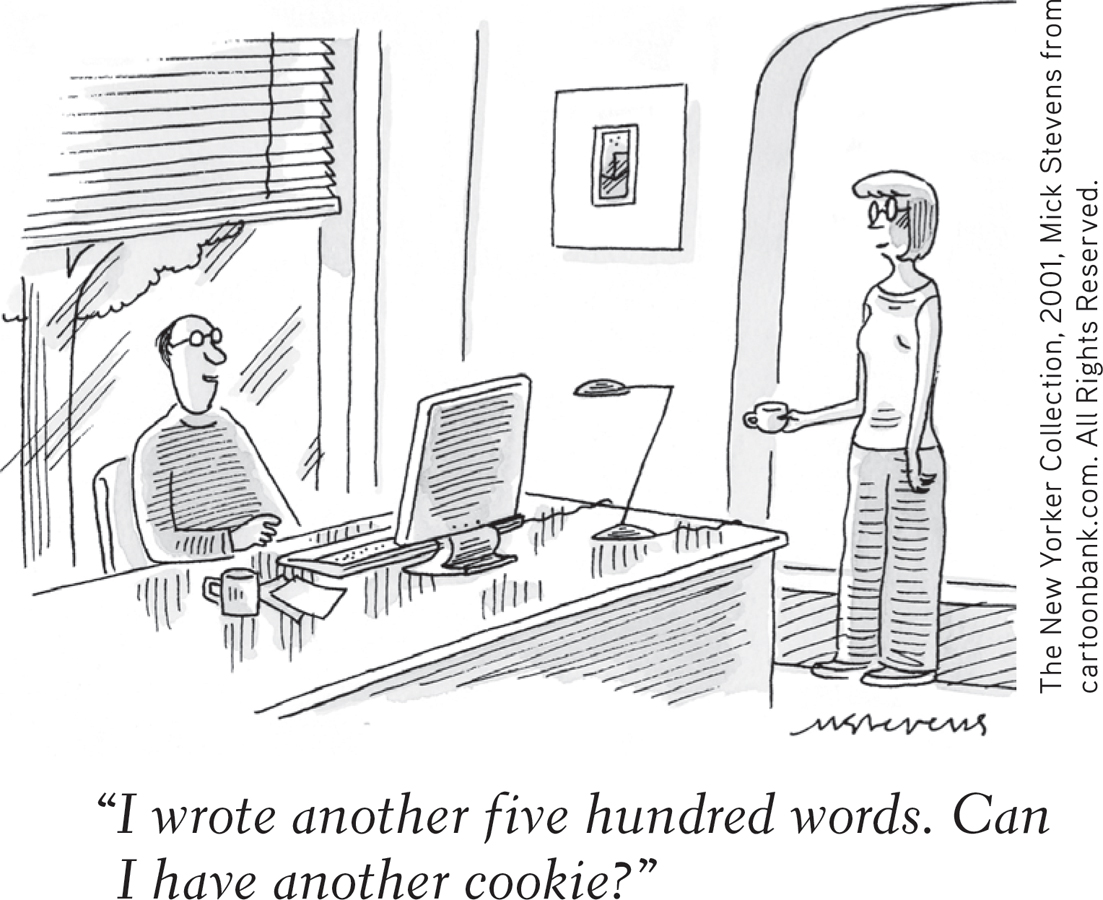

- Reinforce the desired behavior. To increase your study time, give yourself a reward (a snack or some activity you enjoy) only after you finish your extra hour of study. Agree with your friends that you will join them for weekend activities only if you have met your realistic weekly studying goal.

- Reduce the rewards gradually. As your new behaviors become more habitual, give yourself a mental pat on the back instead of a cookie.