24.2 Encoding Memories

Dual-Track Memory: Effortful Versus Automatic Processing

For a 14-minute explanation and demonstration of our memory systems, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Models of Memory.

For a 14-minute explanation and demonstration of our memory systems, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Models of Memory.

24-

Atkinson and Shiffrin’s model focused on how we process our explicit memories—the facts and experiences that we can consciously know and declare (thus, also called declarative memories). But our mind has a second, unconscious track. We encode explicit memories through conscious effortful processing. Behind the scenes, other information skips the conscious encoding track and barges directly into storage. This automatic processing, which happens without our awareness, produces implicit memories (also called nondeclarative memories).

Automatic Processing and Implicit Memories

24-

Our implicit memories include procedural memory for automatic skills (such as how to ride a bike) and classically conditioned associations among stimuli. If attacked by a dog in childhood, years later you may, without recalling the conditioned association, automatically tense up as a dog approaches.

Without conscious effort you also automatically process information about

- space. While studying, you often encode the place on a page where certain material appears; later, when you want to retrieve the information, you may visualize its location on the page.

- time. While going about your day, you unintentionally note the sequence of its events. Later, realizing you’ve left your coat somewhere, the event sequence your brain automatically encoded will enable you to retrace your steps.

- frequency. You effortlessly keep track of how many times things happen, as when you realize, “This is the third time I’ve run into her today.”

Our two-

Effortful Processing and Explicit Memories

Automatic processing happens effortlessly. When you see words in your native language, perhaps on the side of a delivery truck, you can’t help but read them and register their meaning. Learning to read wasn’t automatic. You may recall working hard to pick out letters and connect them to certain sounds. But with experience and practice, your reading became automatic. Imagine now learning to read reversed sentences like this:

.citamotua emoceb nac gnissecorp luftroffE

At first, this requires effort, but after enough practice, you would also perform this task much more automatically. We develop many skills in this way: driving, texting, and speaking a new language.

Sensory Memory

24-

Sensory memory (recall Figure 24.3) feeds our active working memory, recording momentary images of scenes or echoes of sounds. How much of this page could you sense and recall with less exposure than a lightning flash? In one experiment, people viewed three rows of three letters each, for only one-

Figure 24.5

Figure 24.5Total recall—

Was it because they had insufficient time to glimpse them? No. George Sperling cleverly demonstrated that people actually could see and recall all the letters, but only momentarily. Rather than ask them to recall all nine letters at once, he sounded a high, medium, or low tone immediately after flashing the nine letters. This tone directed participants to report only the letters of the top, middle, or bottom row, respectively. Now they rarely missed a letter, showing that all nine letters were momentarily available for recall.

Sperling’s experiment demonstrated iconic memory, a fleeting sensory memory of visual stimuli. For a few tenths of a second, our eyes register a photographic or picture-

We also have an impeccable, though fleeting, memory for auditory stimuli, called echoic memory (Cowan, 1988; Lu et al., 1992). Picture yourself in conversation, as your attention veers to your smartphone screen. If your mildly irked companion tests you by asking, “What did I just say?” you can recover the last few words from your mind’s echo chamber. Auditory echoes tend to linger for 3 or 4 seconds.

Capacity of Short-

24-

Recall that working memory is an active stage, where our brains make sense of incoming information and link it with stored memories. What are the limits of what we can hold in this middle stage?

George Miller (1956) proposed that we can store about seven bits of information (give or take two) in short-

After Miller’s 2012 death, his daughter recalled his best moment of golf: “He made the one and only hole-in-one of his life at the age of 77, on the seventh green … with a seven iron. He loved that” (quoted by Vitello, 2012).

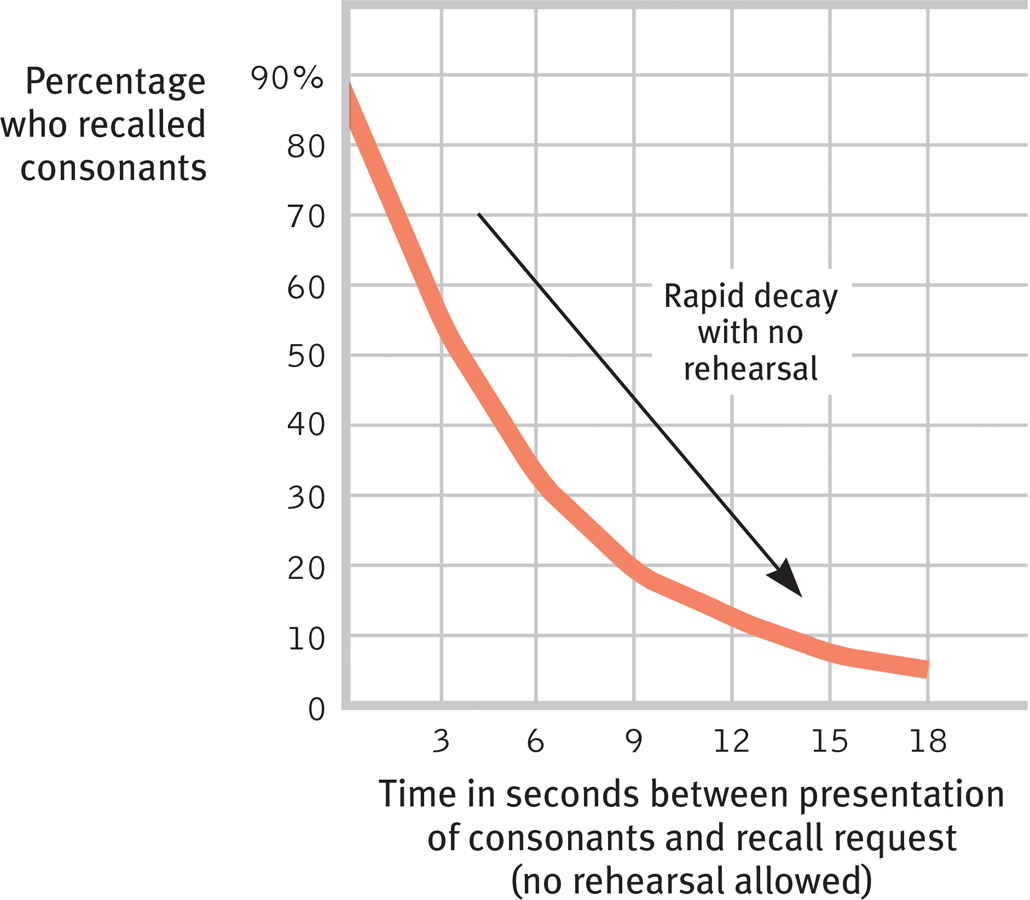

Other researchers have confirmed that we can, if nothing distracts us, recall about seven digits, or about six letters or five words (Baddeley et al., 1975). How quickly do our short-

Figure 24.6

Figure 24.6Short-

Working memory capacity varies, depending on age and other factors. Compared with children and older adults, young adults have more working memory capacity, so they can use their mental workspace more efficiently. This means their ability to multitask is relatively greater. But whatever our age, we do better and more efficient work when focused, without distractions, on one task at a time. The bottom line: It’s probably a bad idea to try to watch TV, text your friends, and write a psychology paper all at the same time (Willingham, 2010)!

For a review of memory stages and a test of your own short-term memory capacity, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Short-Term Memory.

For a review of memory stages and a test of your own short-term memory capacity, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Short-Term Memory.

Unlike short-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is the difference between automatic and effortful processing, and what are some examples of each?

Automatic processing occurs unconsciously (automatically) for such things as the sequence and frequency of a day’s events, and reading and comprehending words in our own language. Effortful processing requires attention and awareness and happens, for example, when we work hard to learn new material in class, or new lines for a play.

- At which of Atkinson-Shiffrin’s three memory stages would iconic and echoic memory occur?

sensory memory

Effortful Processing Strategies

24-

Several effortful processing strategies can boost our ability to form new memories. Later, when we try to retrieve a memory, these strategies can make the difference between success and failure.

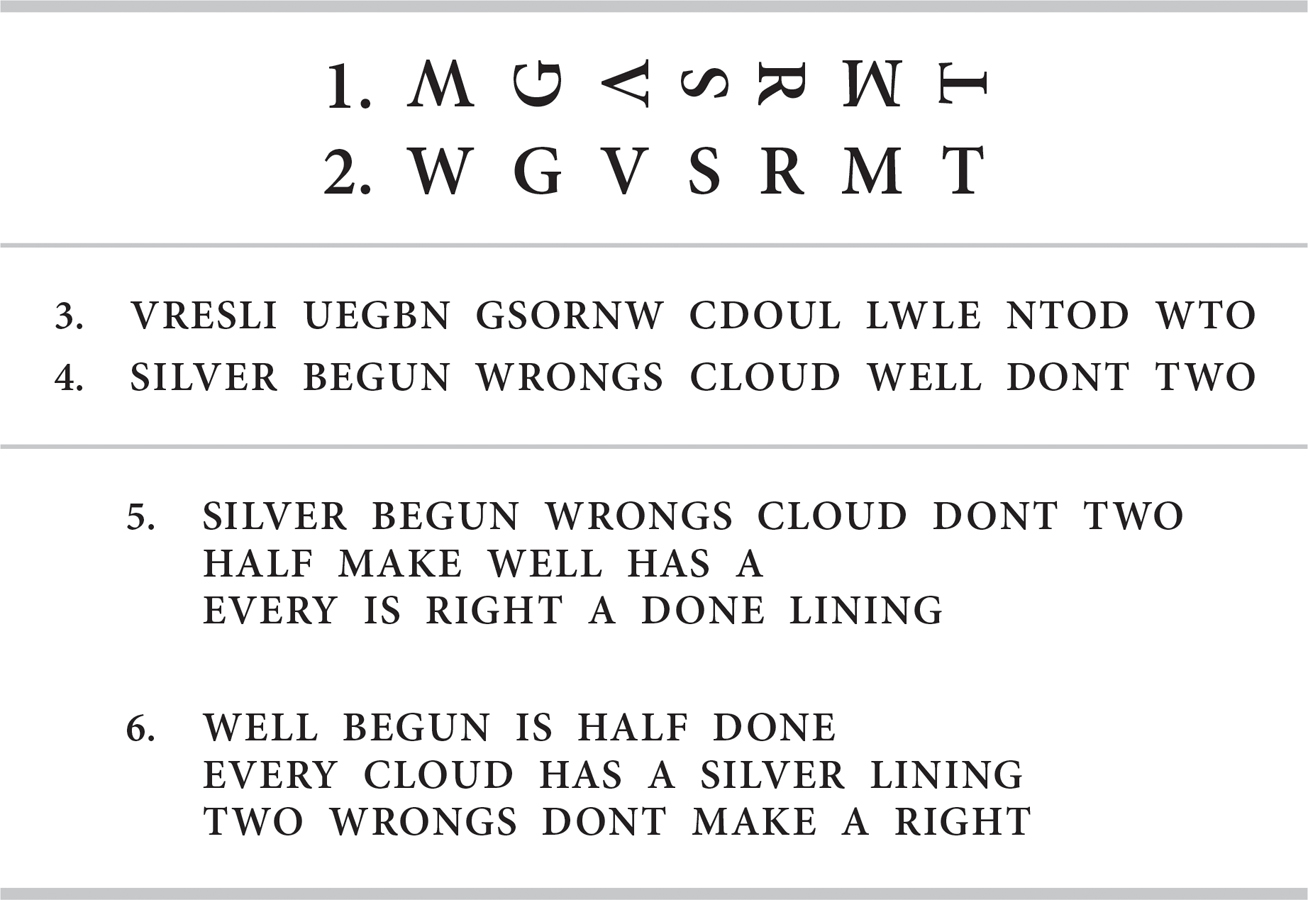

CHUNKING Glance for a few seconds at the first set of letters in FIGURE 24.7, then look away and try to reproduce what you saw. Impossible, yes? But you can easily reproduce set 2, which is no less complex. Similarly, you will probably remember sets 4 and 6 more easily than the same elements in sets 3 and 5. As this demonstrates, chunking information—

Figure 24.7

Figure 24.7Effects of chunking on memory When Doug Hintzman (1978) showed people information similar to this, they recalled it more easily when it was organized into meaningful units, such as letters, words, and phrases.

Chunking usually occurs so naturally that we take it for granted. If you are a native English speaker, you can reproduce perfectly the 150 or so line segments that make up the words in the three phrases of set 6 in Figure 24.7. It would astonish someone unfamiliar with the language. I am similarly awed at a Chinese reader’s ability to glance at FIGURE 24.8 and then reproduce all the strokes; or of a varsity basketball player’s recall of the positions of the players after a 4-

Figure 24.8

Figure 24.8An example of chunking—

MNEMONICS To help them encode lengthy passages and speeches, ancient Greek scholars and orators developed mnemonics. Many of these memory aids use vivid imagery, because we are particularly good at remembering mental pictures. We more easily remember concrete, visualizable words than we do abstract words. (When we quiz you later, which three of these words—

The peg-

When combined, chunking and mnemonic techniques can be great memory aids for unfamiliar material. Want to remember the colors of the rainbow in order of wavelength? Think of the mnemonic ROY G. BIV (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet). Need to recall the names of North America’s five Great Lakes? Just remember HOMES (Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, Superior). In each case, we chunk information into a more familiar form by creating a word (called an acronym) from the first letters of the to-

HIERARCHIES When people develop expertise in an area, they process information not only in chunks but also in hierarchies composed of a few broad concepts divided and subdivided into narrower concepts and facts. (Figure 25.4 in the next module provides a hierarchy of our automatic and effortful memory processing systems.) Organizing knowledge in hierarchies helps us retrieve information efficiently, as Gordon Bower and his colleagues (1969) demonstrated by presenting words either randomly or grouped into categories. When the words were grouped, recall was two to three times better. Such results show the benefits of organizing what you study—

Distributed PracticeWe retain information better when our encoding is distributed over time. More than 300 experiments over the past century have consistently revealed the benefits of this spacing effect (Cepeda et al., 2006). Massed practice (cramming) can produce speedy short-

Distributing your learning over several months, rather than over a shorter term, can even help you retain information for a lifetime. In a 9-

“The mind is slow in unlearning what it has been long in learning.”

Roman philosopher Seneca (4 b.c.e.–65 c.e.)

One effective way to distribute practice is repeated self-

The point to remember: Spaced study and self-

Levels of Processing

24-

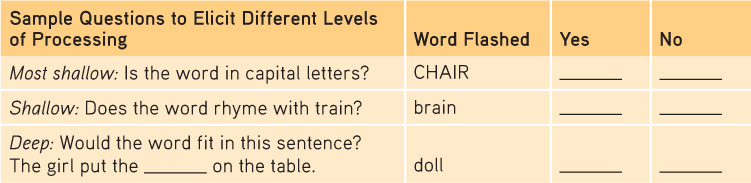

Memory researchers have discovered that we process verbal information at different levels, and that depth of processing affects our long-

In one classic experiment, researchers Fergus Craik and Endel Tulving (1975) flashed words at people. Then they asked questions that would elicit different levels of processing. To experience the task yourself, rapidly answer the following sample questions:

Which type of processing would best prepare you to recognize the words at a later time? In Craik and Tulving’s experiment, the deeper, semantic processing triggered by the third question yielded a much better memory than did the shallower processing elicited by the second question or the very shallow processing elicited by the first question (which was especially ineffective).

Making Material Personally MeaningfulIf new information is not meaningful or related to our experience, we have trouble processing it. Put yourself in the place of the students who were asked to remember the following recorded passage:

The procedure is actually quite simple. First you arrange things into different groups. Of course, one pile may be sufficient depending on how much there is to do…. After the procedure is completed, one arranges the materials into different groups again. Then they can be put into their appropriate places. Eventually they will be used once more and the whole cycle will then have to be repeated. However, that is part of life.

When the students heard the paragraph you have just read, without a meaningful context, they remembered little of it (Bransford & Johnson, 1972). When told the paragraph described washing clothes (something meaningful), they remembered much more of it—

Can you repeat the sentence about the rioter that we gave you at this module’s beginning? (“The angry rioter threw . . .”)?

Perhaps, like those in an experiment by William Brewer (1977), you recalled the sentence by the meaning you encoded when you read it (for example, “The angry rioter threw the rock through the window”) and not as it was written (“The angry rioter threw the rock at the window”). Referring to such mental mismatches, some researchers have likened our minds to theater directors who, given a raw script, imagine the finished stage production (Bower & Morrow, 1990). Asked later what we heard or read, we recall not the literal text but what we encoded. Thus, studying for an exam, you may remember your lecture notes rather than the lecture itself.

In the discussion of mnemonics, we gave you six words and told you we would quiz you about them later. How many of these words can you now recall? Of these, how many are high-imagery words? How many are low-imagery? (You can check your list against the six words below.)

Bicycle, void, cigarette, inherent, fire, process

We can avoid some of these mismatches by rephrasing information into meaningful terms. From his experiments on himself, Ebbinghaus estimated that, compared with learning nonsense material, learning meaningful material required one-

Psychologist-

We have especially good recall for information we can meaningfully relate to ourselves. Asked how well certain adjectives describe someone else, we often forget them; asked how well the adjectives describe us, we remember the words well. This tendency, called the self-

The point to remember: The amount remembered depends both on the time spent learning and on your making it meaningful for deep processing.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Which strategies are better for long-term retention: cramming and rereading material, or spreading out learning over time and repeatedly testing yourself?

Although cramming may lead to short-

- If you try to make the material you are learning personally meaningful, are you processing at a shallow or a deep level? Which level leads to greater retention?

Making material personally meaningful involves processing at a deep level, because you are processing semantically—based on the meaning of the words. Deep processing leads to greater retention.