25.2 Memory Retrieval

After the magic of brain encoding and storage, we still have the daunting task of retrieving the information. What triggers retrieval?

Retrieval Cues

25-

Imagine a spider suspended in the middle of her web, held up by the many strands extending outward from her in all directions to different points. If you were to trace a pathway to the spider, you would first need to create a path from one of these anchor points and then follow the strand down into the web.

“Memory is not like a container that gradually fills up; it is more like a tree growing hooks onto which memories are hung.”

Peter Russell, The Brain Book, 1979

The process of retrieving a memory follows a similar principle, because memories are held in storage by a web of associations, each piece of information interconnected with others. When you encode into memory a target piece of information, such as the name of the person sitting next to you in class, you associate with it other bits of information about your surroundings, mood, seating position, and so on. These bits can serve as retrieval cues that you can later use to access the information. The more retrieval cues you have, the better your chances of finding a route to the suspended memory.

The best retrieval cues come from associations we form at the time we encode a memory—

I knew I had been somewhere, and had done particular things with certain people, but where? I could not put the conversations … into a context. There was no background, no features against which to identify the place. Normally, the memories of people you have spoken to during the day are stored in frames which include the background.

For an 8-minute synopsis of how we access what’s stored in our brain, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Memory Retrieval.

For an 8-minute synopsis of how we access what’s stored in our brain, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Memory Retrieval.

PrimingOften our associations are activated without our awareness. Philosopher-

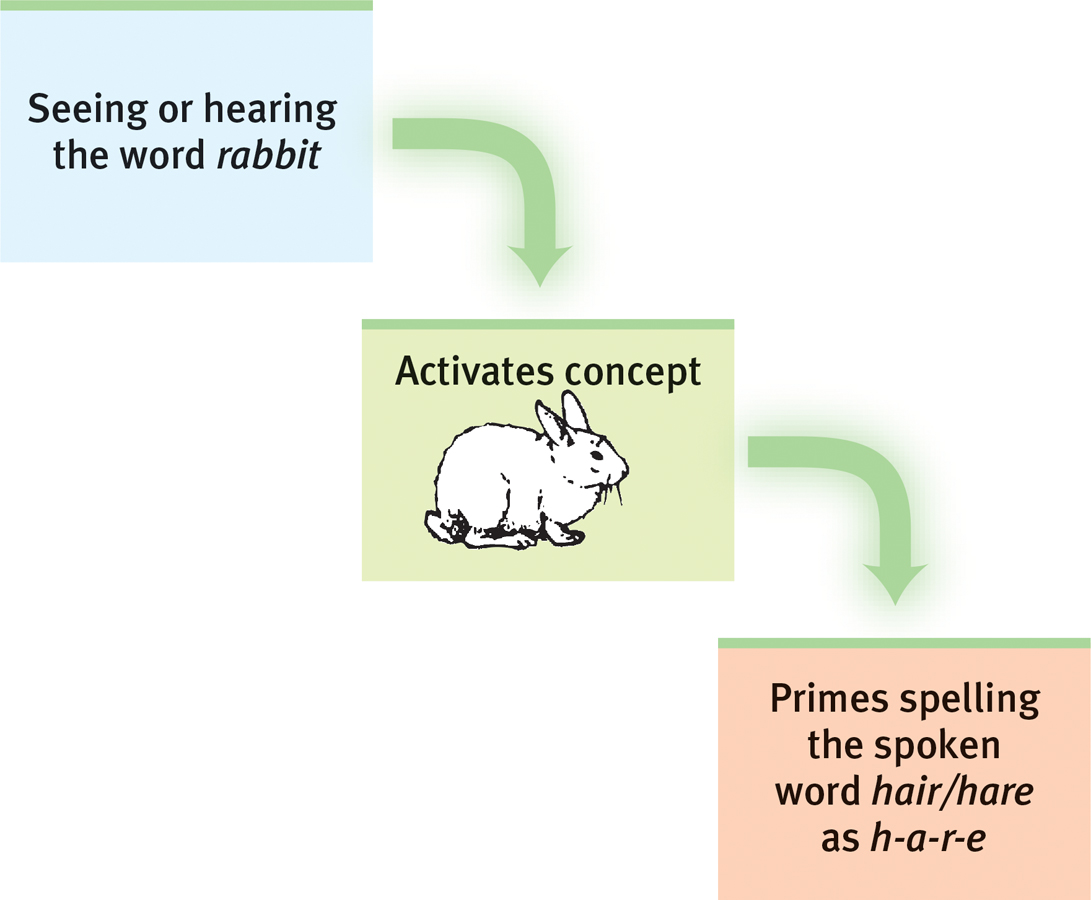

Figure 25.5

Figure 25.5Priming—

Ask a friend two rapid-fire questions: (a) How do you pronounce the word spelled by the letters s-h-o-p? (b) What do you do when you come to a green light? If your friend answers “stop” to the second question, you have demonstrated priming.

Priming is often “memoryless memory”—invisible memory, without your conscious awareness. If, walking down a hallway, you see a poster of a missing child, you will then unconsciously be primed to interpret an ambiguous adult-

Priming can influence behaviors as well (Herring et al., 2013). In one study, participants primed with money-

Context-

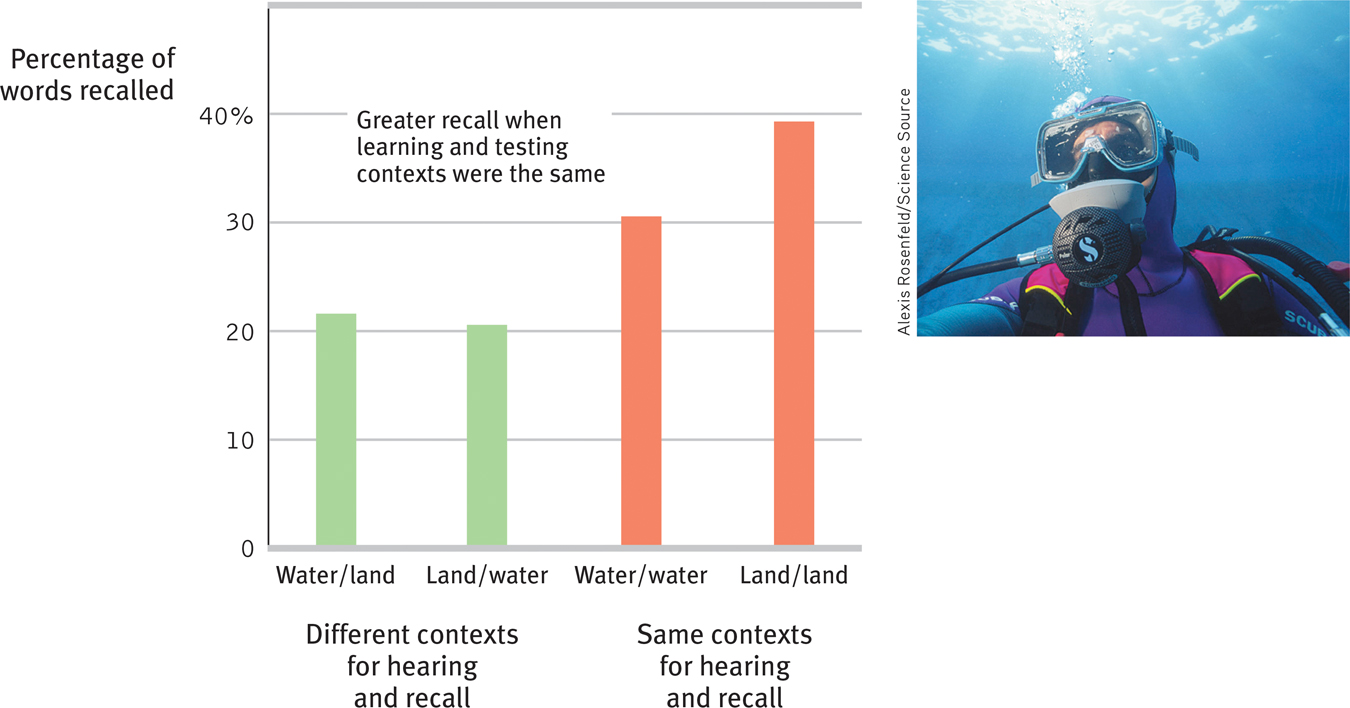

Figure 25.6

Figure 25.6The effects of context on memory Words heard underwater were best recalled underwater; words heard on land were best recalled on land. (Data from Godden & Baddeley, 1975.)

By contrast, experiencing something outside the usual setting can be confusing. Have you ever run into your doctor in an unusual place, such as at the store or park? You knew the person but struggled to figure out who it was and how you were acquainted? The encoding specificity principle helps us understand how cues specific to an event or person will most effectively trigger that memory. In new settings, you may not have the memory cues needed for speedy face recognition. Our memories depend on context, and on the cues we have associated with that context.

In several experiments, Carolyn Rovee-

State-

Our mood states provide an example of memory’s state dependence. Emotions that accompany good or bad events become retrieval cues (Fiedler et al., 2001). Thus, our memories are somewhat mood congruent. If you’ve had a bad evening—

Knowing this mood-

“When a feeling was there, they felt as if it would never go; when it was gone, they felt as if it had never been; when it returned, they felt as if it had never gone.”

George MacDonald, What’s Mine’s Mine, 1886

Mood effects on retrieval help explain why our moods persist. When happy, we recall happy events and therefore see the world as a happy place, which helps prolong our good mood. When depressed, we recall sad events, which darkens our interpretations of current events. For those of us with a predisposition to depression, this process can help maintain a vicious, dark cycle.

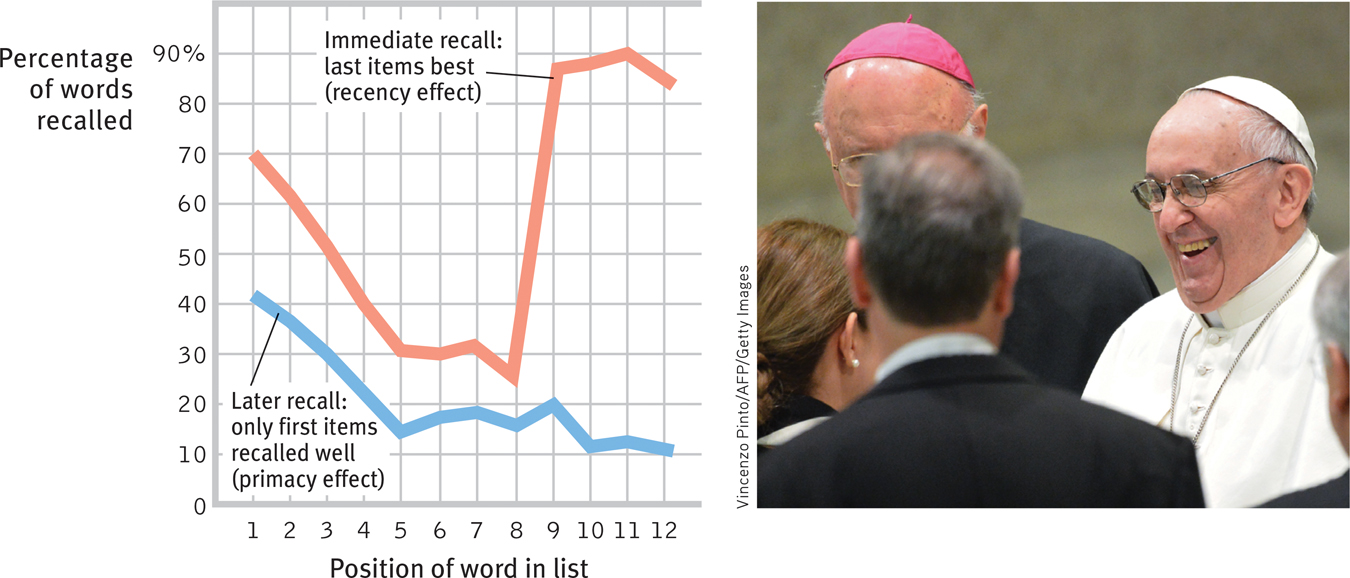

Serial Position EffectAnother memory-

Don’t count on it. Because you have spent more time rehearsing the earlier names than the later ones, those are the names you’ll probably recall more easily the next day. In experiments, when people viewed a list of items (words, names, dates, even odors) and immediately tried to recall them in any order, they fell prey to the serial position effect (Reed, 2000). They briefly recalled the last items especially quickly and well (a recency effect), perhaps because those last items were still in working memory. But after a delay, when their attention was elsewhere, their recall was best for the first items (a primacy effect; see FIGURE 25.7).

Figure 25.7

Figure 25.7The serial position effect Immediately after Pope Francis made his way through this receiving line of special guests, he would probably have recalled the names of the last few people best (recency effect). But later he may have been able to recall the first few people best (primacy effect).

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is priming?

Priming is the activation (often without our awareness) of associations. Seeing a gun, for example, might temporarily predispose someone to interpret an ambiguous face as threatening or to recall a boss as nasty.

- When we are tested immediately after viewing a list of words, we tend to recall the first and last items best, which is known as the__________ __________ effect.

serial position