26.1 Forgetting

26-

AMID ALL THE APPLAUSE FOR memory—

Later in this module we will ask you to recall this sentence: The fish attacked the swimmer.

A more recent case of a life overtaken by memory is “A. J.,” whose experience has been studied and verified by a University of California at Irvine research team, along with several dozen other “highly superior autobiographical memory” cases (McGaugh & LePort, 2014; Parker et al., 2006). A. J., who has identified herself as Jill Price, compares her memory to “a running movie that never stops. It’s like a split screen. I’ll be talking to someone and seeing something else…. Whenever I see a date flash on the television (or anywhere for that matter) I automatically go back to that day and remember where I was, what I was doing, what day it fell on, and on and on and on and on. It is nonstop, uncontrollable, and totally exhausting.” A good memory is helpful, but so is the ability to forget. If a memory-

More often, however, our unpredictable memory dismays and frustrates us. Memories are quirky. My [DM] own memory can easily call up such episodes as that wonderful first kiss with the woman I love, or trivial facts like the air mileage from London to Detroit. Then it abandons me when I discover I have failed to encode, store, or retrieve a student’s name or where I left my sunglasses.

Forgetting and the Two-Track Mind

For some, memory loss is severe and permanent. Consider Henry Molaison (known as “H. M.,” 1926–

Molaison suffered from anterograde amnesia—he could recall his past, but he could not form new memories. (Those who cannot recall their past—

Neurologist Oliver Sacks (1985, pp. 26–

When Jimmie gave his age as 19, Sacks set a mirror before him: “Look in the mirror and tell me what you see. Is that a 19-

Jimmie turned ashen, gripped the chair, cursed, then became frantic: “What’s going on? What’s happened to me? Is this a nightmare? Am I crazy? Is this a joke?” When his attention was diverted to some children playing baseball, his panic ended, the dreadful mirror forgotten.

Sacks showed Jimmie a photo from National Geographic. “What is this?” he asked.

“It’s the Moon,” Jimmie replied.

“No, it’s not,” Sacks answered. “It’s a picture of the Earth taken from the Moon.”

“Doc, you’re kidding! Someone would’ve had to get a camera up there!”

“ Naturally.”

“Hell! You’re joking—

Careful testing of these unique people reveals something even stranger: Although incapable of recalling new facts or anything they have done recently, Molaison, Jimmie, and others with similar conditions can learn nonverbal tasks. Shown hard-

Molaison and Jimmie lost their ability to form new explicit memories, but their automatic processing ability remained intact. Like Alzheimer’s patients, whose explicit memories for new people and events are lost, they could form new implicit memories (Lustig & Buckner, 2004). These patients can learn how to do something, but they will have no conscious recall of learning their new skill. Such sad cases confirm that we have two distinct memory systems, controlled by different parts of the brain.

For most of us, forgetting is a less drastic process. Let’s consider some of the reasons we forget.

Encoding Failure

For a 6-minute example of another dramatic case—of an accomplished musician who has lost the ability to form new memories-visit LaunchPad’s Video—Clive Wearing: Living Without Memory.

For a 6-minute example of another dramatic case—of an accomplished musician who has lost the ability to form new memories-visit LaunchPad’s Video—Clive Wearing: Living Without Memory.

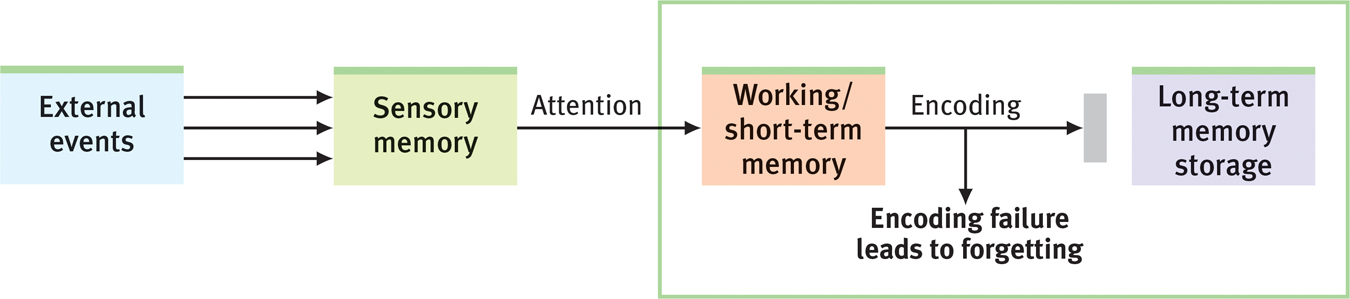

Much of what we sense we never notice, and what we fail to encode, we will never remember (FIGURE 26.1). The English novelist and critic C. S. Lewis (1967, p. 107) described the enormity of what we never encode:

Each of us finds that in [our] own life every moment of time is completely filled. [We are] bombarded every second by sensations, emotions, thoughts … nine-

Figure 26.1

Figure 26.1Forgetting as encoding failure We cannot remember what we have not encoded.

Age can affect encoding efficiency. The brain areas that jump into action when young adults encode new information are less responsive in older adults. This slower encoding helps explain age-

But no matter how young we are, we selectively attend to few of the myriad sights and sounds continually bombarding us. Consider this example: If you live in the United States, you have looked at thousands of pennies in your lifetime. You can surely recall their color and size, but can you recall what the side with the head looks like? If not, let’s make the memory test easier: If you are familiar with U.S. coins, can you, in FIGURE 26.2, just recognize the real thing? Most people cannot (Nickerson & Adams, 1979). Likewise, few British people can draw from memory the details of a one-

Figure 26.2

Figure 26.2Test your memory Which of these U.S. pennies is the real thing? (If you live outside the United States, try drawing one of your own country’s coins.) (From Nickerson & Adams, 1979.) See answer below.

The first penny (a) is the real penny.

Storage Decay

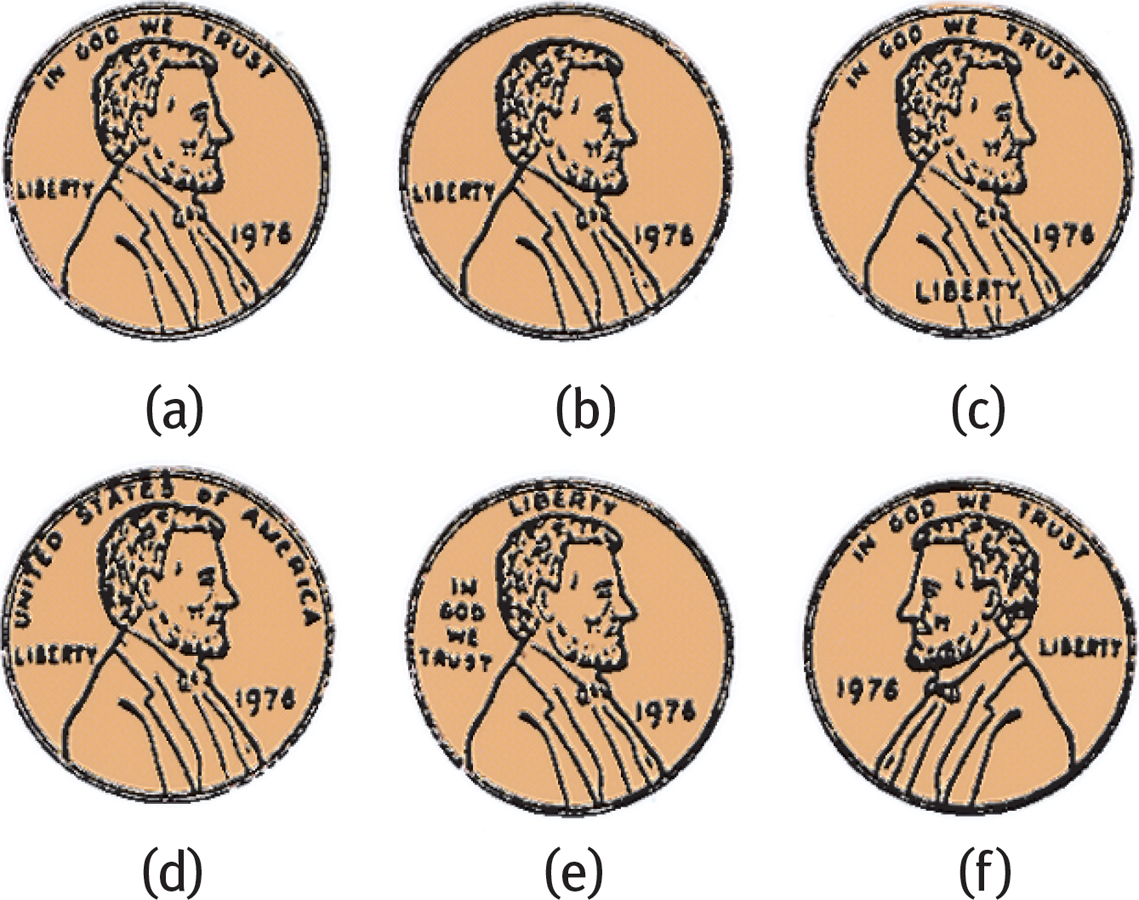

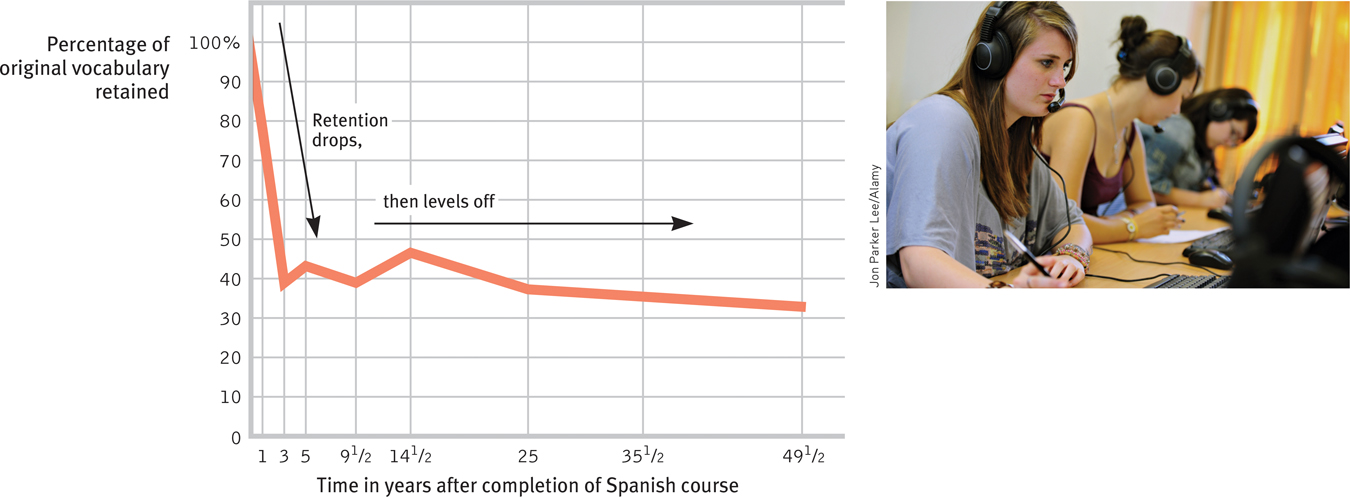

Even after encoding something well, we sometimes later forget it. To study the durability of stored memories, Hermann Ebbinghaus (1885) learned lists of nonsense syllables and measured how much he retained when relearning each list, from 20 minutes to 30 days later. The result, confirmed by later experiments, was his famous forgetting curve: The course of forgetting is initially rapid, then levels off with time (FIGURE 26.3; Wixted & Ebbesen, 1991). Harry Bahrick (1984) found a similar forgetting curve for Spanish vocabulary learned in school. Compared with those just completing a high school or college Spanish course, people 3 years out of school had forgotten much of what they had learned (FIGURE 26.4). However, what people remembered then, they still remembered 25 and more years later. Their forgetting had leveled off.

Figure 26.3

Figure 26.3Ebbinghaus’ forgetting curve After learning lists of nonsense syllables, such as YOX and JIH, Ebbinghaus studied how much he retained up to 30 days later. He found that memory for novel information fades quickly, then levels out. (Data from Ebbinghaus, 1885.)

Figure 26.4

Figure 26.4The forgetting curve for Spanish learned in school Compared with people just completing a Spanish course, those 3 years out of the course remembered much less (on a vocabulary recognition test). Compared with the 3-

One explanation for these forgetting curves is a gradual fading of the physical memory trace. Cognitive neuroscientists are getting closer to solving the mystery of the physical storage of memory and are increasing our understanding of how memory storage could decay. Like books you can’t find in your campus library, memories may be inaccessible for many reasons. Some were never acquired (not encoded). Others were discarded (stored memories decay). And others are out of reach because we can’t retrieve them.

Retrieval Failure

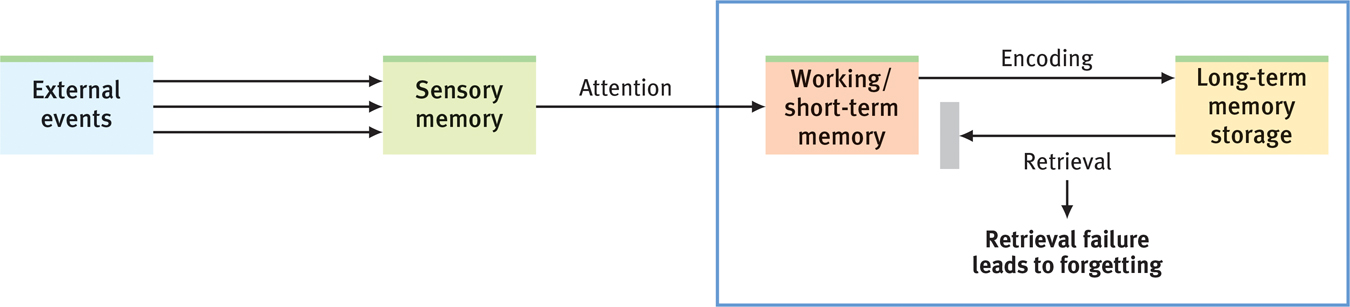

Often, forgetting is not memories faded but memories unretrieved. We store in long-

Figure 26.5

Figure 26.5Retrieval failure Sometimes even stored information cannot be accessed, which leads to forgetting.

Do you recall the gist of the sentence we asked you to remember? If not, does the word shark serve as a retrieval cue? Experiments show that shark (likely what you visualized) more readily retrieves the image you stored than does the sentence’s actual word, fish (Anderson et al., 1976). (The sentence was “The fish attacked the swimmer.”)

But retrieval problems occasionally stem from interference and, perhaps, from motivated forgetting.

Deaf persons fluent in sign language experience a parallel “tip of the fingers” phenomenon (Thompson et al., 2005).

InterferenceAs you collect more and more information, your mental attic never fills, but it surely gets cluttered. An ability to tune out clutter helps people to focus, and focusing helps us recall information. Sometimes, however, clutter wins, and new learning and old collide. Proactive (forward-

Retroactive (backward-

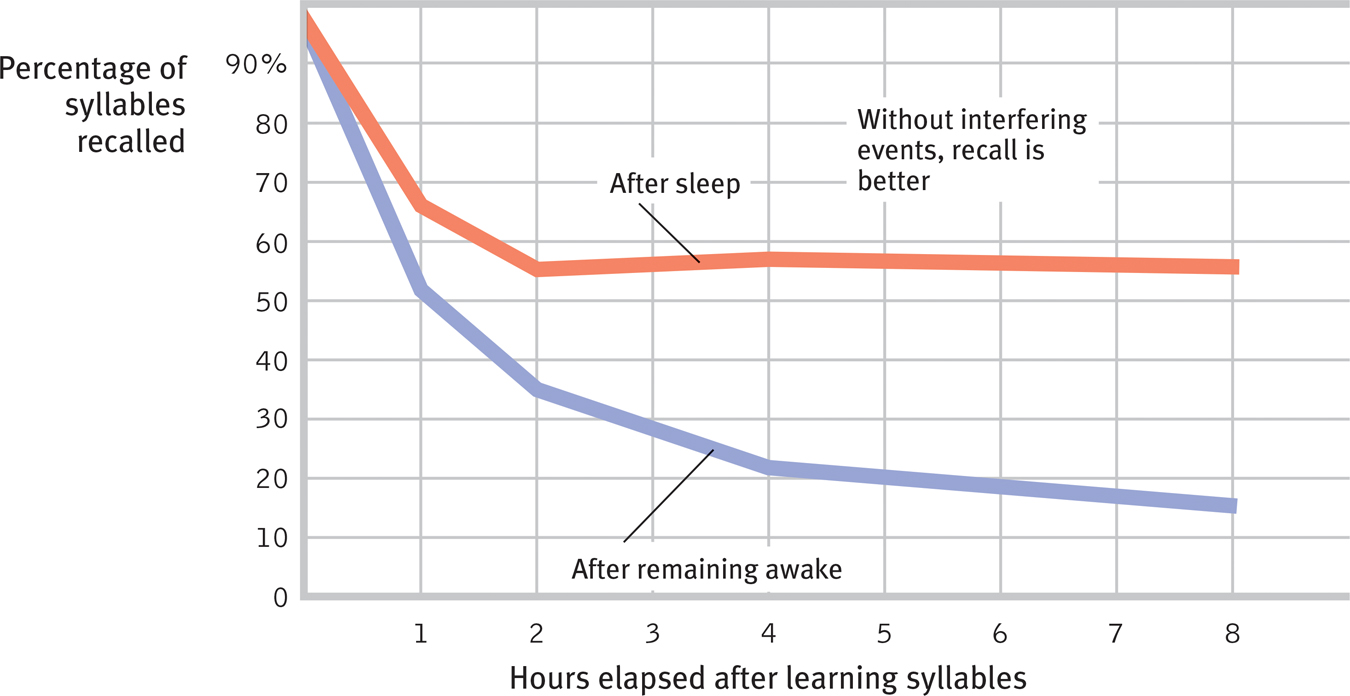

Information presented in the hour before sleep is protected from retroactive interference because the opportunity for interfering events is minimized (Diekelmann & Born, 2010; Nesca & Koulack, 1994). Researchers John Jenkins and Karl Dallenbach (1924) first discovered this in a now-

Figure 26.6

Figure 26.6Retroactive interference More forgetting occurred when a person stayed awake and experienced other new material. (Data from Jenkins & Dallenbach, 1924.)

The hour before sleep is a good time to commit information to memory (Scullin & McDaniel, 2010), though information presented in the seconds just before sleep is seldom remembered (Wyatt & Bootzin, 1994). If you’re considering learning while sleeping, forget it. We have little memory for information played aloud in the room during sleep, although the ears do register it (Wood et al., 1992).

Old and new learning do not always compete with each other, of course. Previously learned information (Latin) often facilitates our learning of new information (French). This phenomenon is called positive transfer.

To experience a demonstration and explanation of interference effects on memory, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Forgetting.

To experience a demonstration and explanation of interference effects on memory, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Forgetting.

Motivated ForgettingTo remember our past is often to revise it. Years ago, the huge cookie jar in my [DM] kitchen was jammed with freshly baked chocolate chip cookies. Still more were cooling across racks on the counter. Twenty-

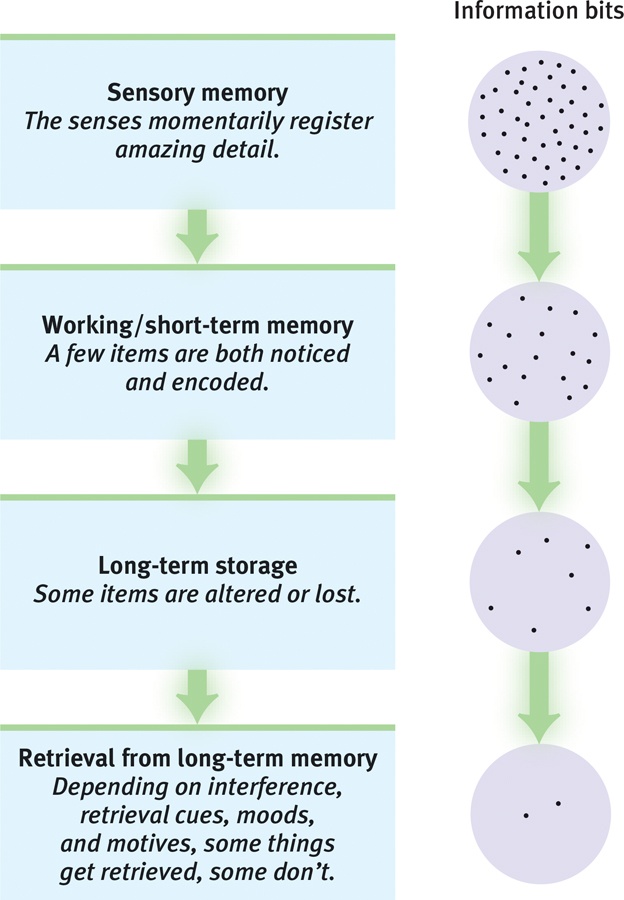

Why do our memories fail us? This happens in part because memory is an “unreliable, self-

FIGURE 26.7 reminds us that as we process information we filter, alter, or lose much of it. So why were my family and I so far off in our estimates of the cookies we had eaten? Was it an encoding problem? (Did we just not notice what we had eaten?) Was it a storage problem? (Might our memories of cookies, like Ebbinghaus’ memory of nonsense syllables, have melted away almost as fast as the cookies themselves?) Or was the information still intact but not retrievable because it would be embarrassing to remember?1

Figure 26.7

Figure 26.7When do we forget? Forgetting can occur at any memory stage. As we process information, we filter, alter, or lose much of it.

Sigmund Freud might have argued that our memory systems self-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What are three ways we forget, and how does each of these happen?

(1) Encoding failure: Unattended information never entered our memory system. (2) Storage decay: Information fades from our memory. (3) Retrieval failure: We cannot access stored information accurately, sometimes due to interference or motivated forgetting.