27.2 Problem Solving: Strategies and Obstacles

27-

One tribute to our rationality is our problem-

Some problems we solve through trial and error. Thomas Edison tried thousands of light bulb filaments before stumbling upon one that worked. For other problems, we use algorithms, step-

Sometimes we puzzle over a problem and the pieces suddenly fall together in a flash of insight—an abrupt, true-

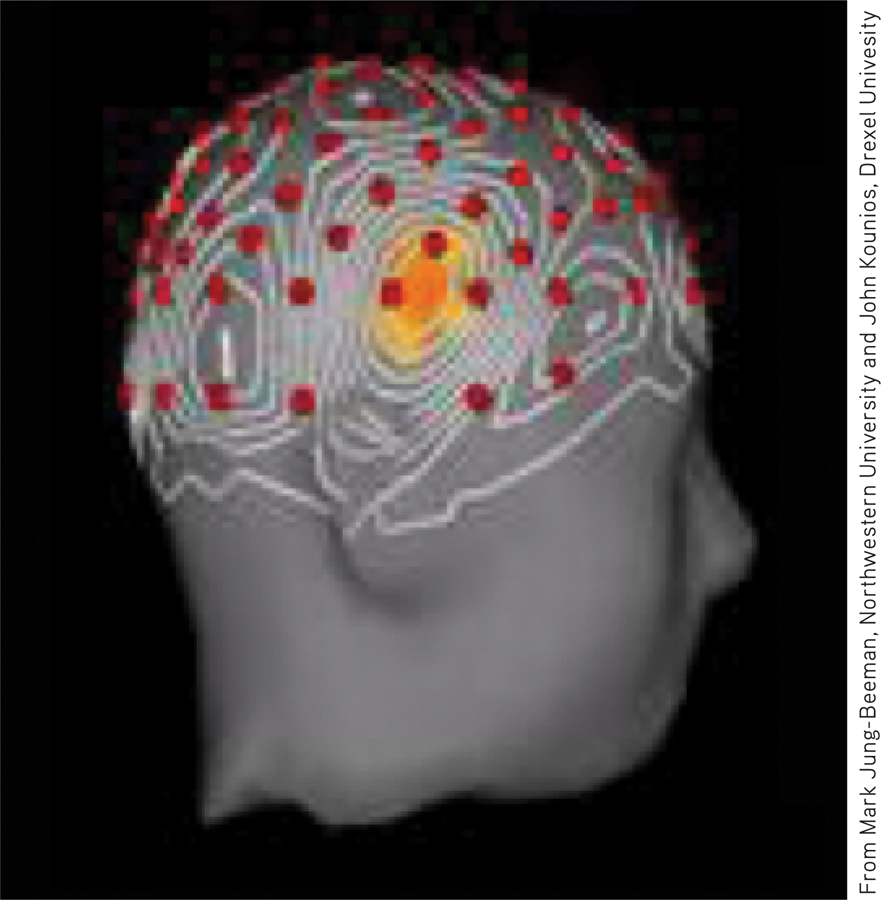

Teams of researchers have identified brain activity associated with sudden flashes of insight (Kounios & Beeman, 2009; Sandkühler & Bhattacharya, 2008). They gave people a problem: Think of a word that will form a compound word or phrase with each of three other words in a set (such as pine, crab, and sauce), and press a button to sound a bell when you know the answer. (If you need a hint: The word is a fruit.2) EEGs or fMRIs (functional MRIs) revealed the problem solver’s brain activity. In the first experiment, about half the solutions were by a sudden Aha! insight. Before the Aha! moment, the problem solvers’ frontal lobes (which are involved in focusing attention) were active, and there was a burst of activity in the right temporal lobe, just above the ear (FIGURE 27.3). In another experiment, researchers used electrical stimulation to decrease left hemisphere activity and increase right hemisphere activity. The result was improved insight, less restrained by the assumptions created by past experience (Chi & Snyder, 2011).

Figure 27.3

Figure 27.3The Aha! moment A burst of right temporal lobe activity accompanied insight solutions to word problems (Jung-

Insight strikes suddenly, with no prior sense of “getting warmer” or feeling close to a solution (Knoblich & Oellinger, 2006; Metcalfe, 1986). When the answer pops into mind (apple!), we feel a happy sense of satisfaction. The joy of a joke may similarly lie in our sudden comprehension of an unexpected ending or a double meaning: “You don’t need a parachute to skydive. You only need a parachute to skydive twice.” Comedian Groucho Marx was a master at this: “I once shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got in my pajamas I’ll never know.”

Inventive as we are, other cognitive tendencies may lead us astray. For example, we more eagerly seek out and favor evidence that supports our ideas than evidence that refutes them (Klayman & Ha, 1987; Skov & Sherman, 1986). Peter Wason (1960) demonstrated this tendency, known as confirmation bias, by giving British university students the three-

“Ordinary people,” said Wason (1981), “evade facts, become inconsistent, or systematically defend themselves against the threat of new information relevant to the issue.” Thus, once people form a belief—

“The human understanding, when any proposition has been once laid down … forces everything else to add fresh support and confirmation.”

Francis Bacon, Novum Organum, 1620

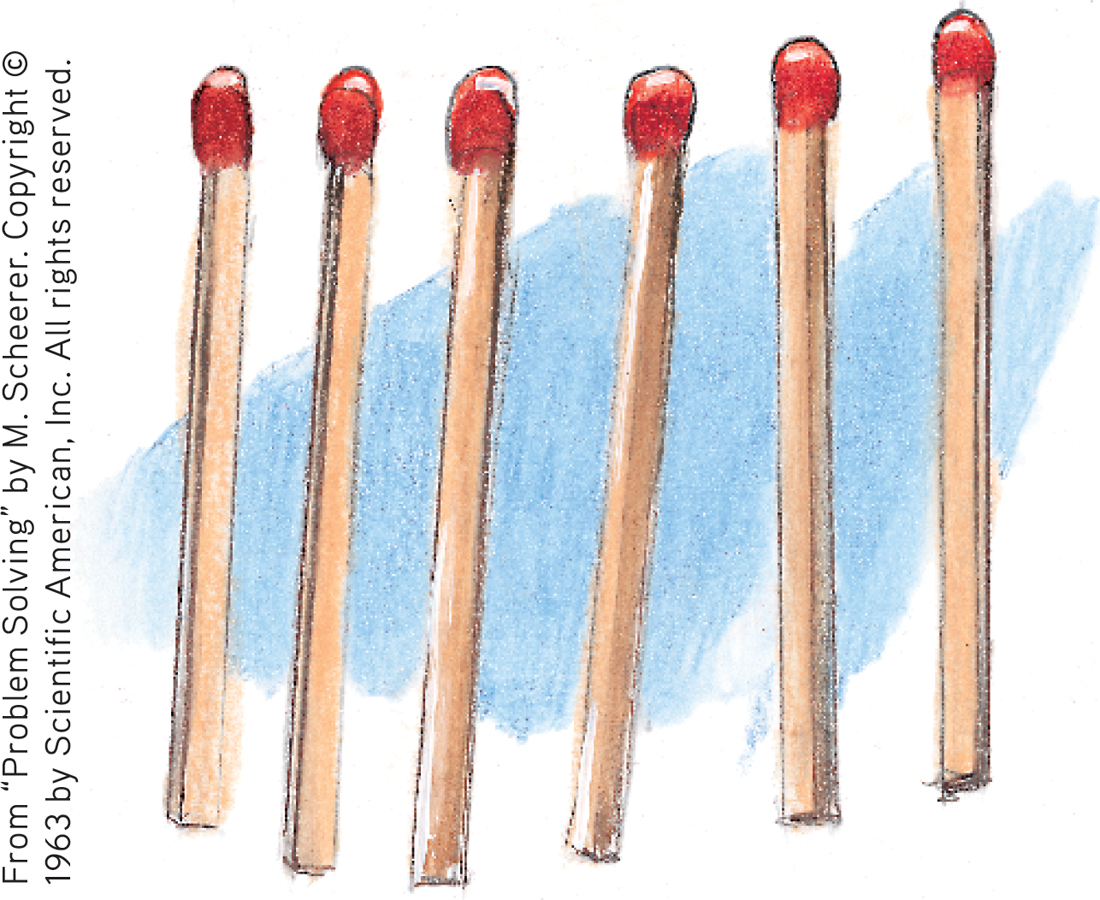

Once we incorrectly represent a problem, it’s hard to restructure how we approach it. If the solution to the matchstick problem in FIGURE 27.4 eludes you, you may be experiencing fixation—an inability to see a problem from a fresh perspective. (For the solution, see FIGURE 27.5.)

Figure 27.4

Figure 27.4The matchstick problem How would you arrange six matches to form four equilateral triangles?

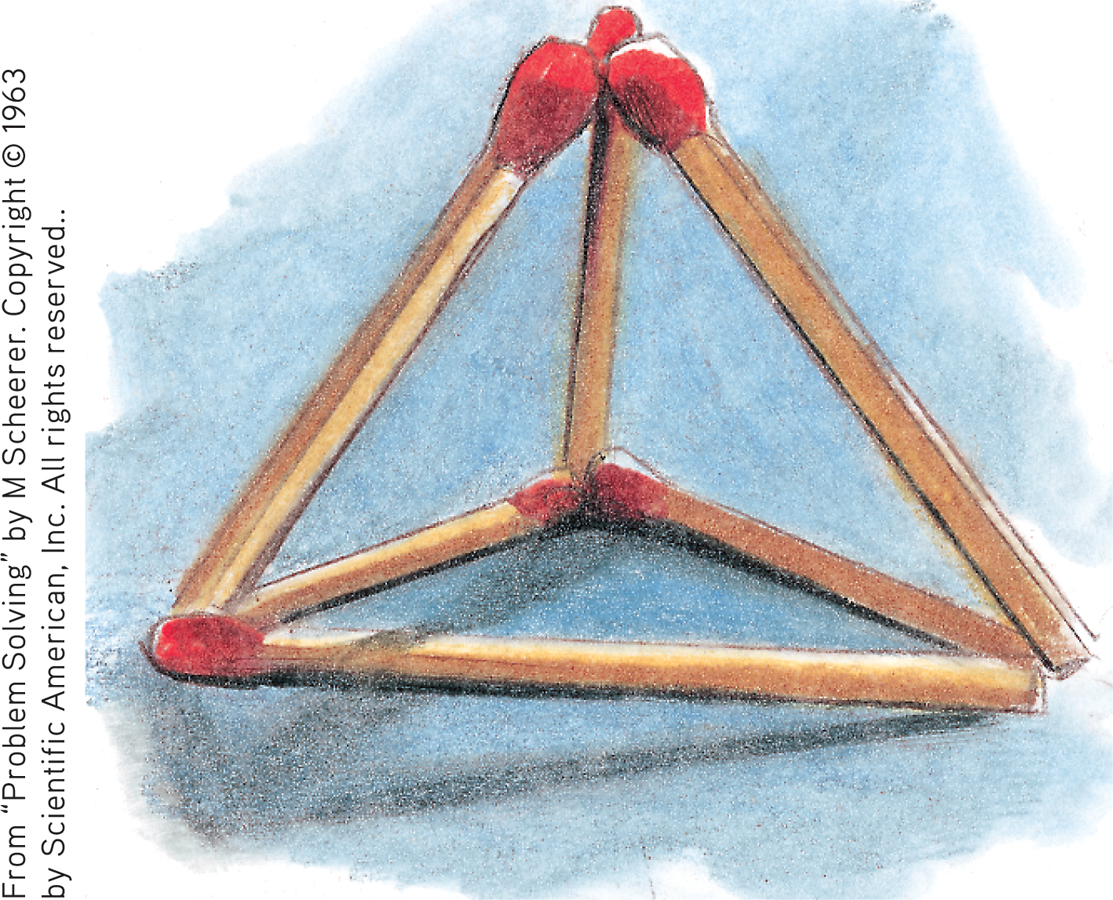

Figure 27.5

Figure 27.5Solution to the matchstick problem To solve this problem, you must view it from a new perspective, breaking the fixation of limiting solutions to two dimensions.

A prime example of fixation is mental set, our tendency to approach a problem with the mind-

Given the sequence O-

Most people have difficulty recognizing that the three final letters are F(ive), S(ix), and S(even). But solving this problem may make the next one easier:

Given the sequence J-

As a perceptual set predisposes what we perceive, a mental set predisposes how we think; sometimes this can be an obstacle to problem solving, as when our mental set from our past experiences with matchsticks predisposes us to arrange them in two dimensions.