27.5 Do Other Species Share Our Cognitive Skills?

27-

Other animals are smarter than we often realize. In her 1908 book, The Animal Mind, pioneering psychologist Margaret Floy Washburn argued that animal consciousness and intelligence can be inferred from their behavior. In 2012, neuroscientists convening at the University of Cambridge added that animal consciousness can also be inferred from their brains: “Nonhuman animals, including all mammals and birds,” possess the neural networks “that generate consciousness” (Low et al., 2012). Consider, then, what animal brains can do.

Using Concepts and Numbers

Even pigeons—

Until his death in 2007, Alex, an African Grey parrot, categorized and named objects (Pepperberg, 2009, 2012, 2013). Among his jaw-

Displaying Insight

Psychologist Wolfgang Köhler (1925) showed that we are not the only creatures to display insight. He placed a piece of fruit and a long stick outside the cage of a chimpanzee named Sultan, beyond his reach. Inside the cage, he placed a short stick, which Sultan grabbed, using it to try to reach the fruit. After several failed attempts, he dropped the stick and seemed to survey the situation. Then suddenly (as if thinking “Aha!”), Sultan jumped up and seized the short stick again. This time, he used it to pull in the longer stick—

Birds, too, have displayed insight. One experiment, by (yes) Christopher Bird and Nathan Emery (2009), has brought to life an Aesop fable in which a thirsty crow was unable to reach the water in a partly filled pitcher. See its solution in FIGURE 27.8a.

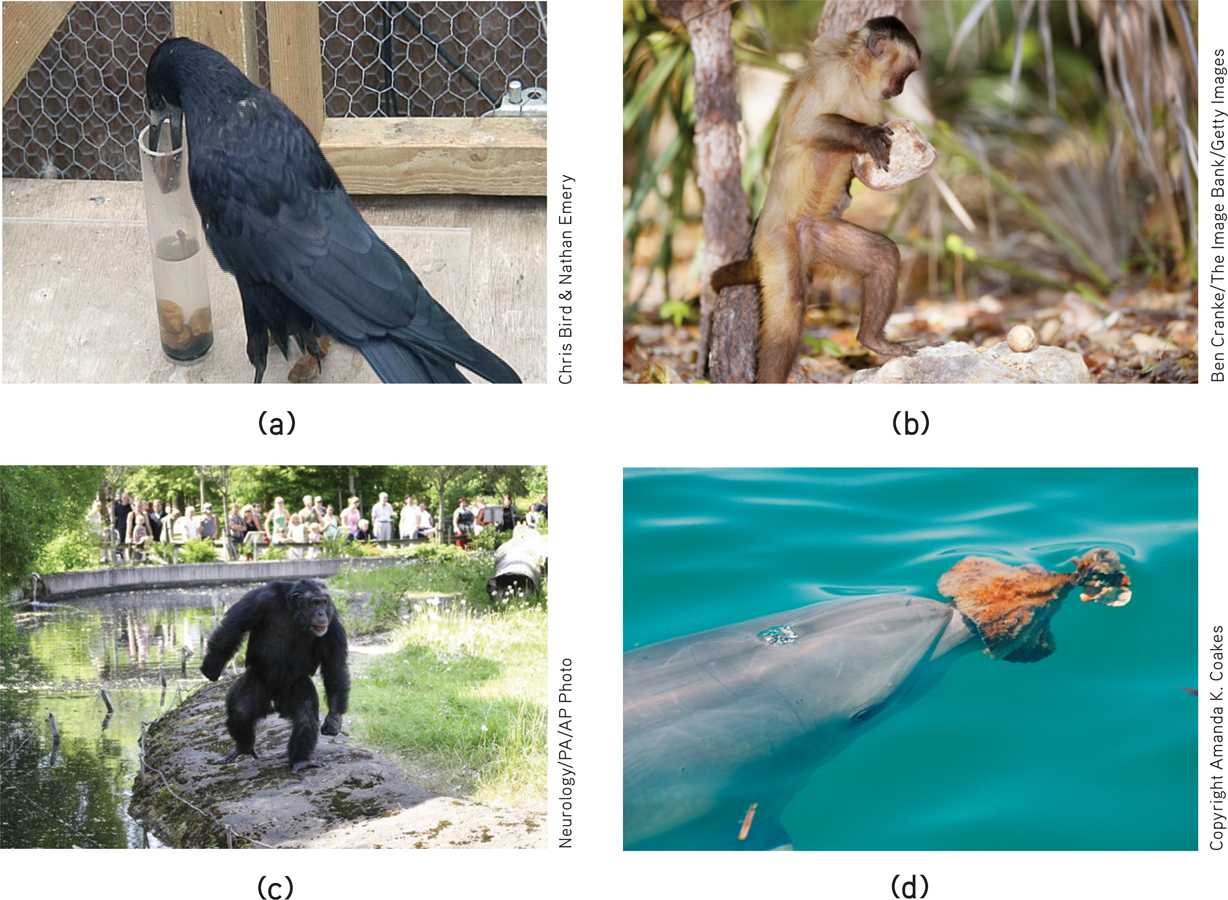

Figure 27.8

Figure 27.8Animal talents (a) Crows studied by Christopher Bird and Nathan Emery (2009) quickly learned to raise the water level in a tube and nab a floating worm by dropping in stones. Other crows have used twigs to probe for insects, and bent strips of metal to reach food. (b) Capuchin monkeys have learned not only to use heavy rocks to crack open palm nuts, but also to test stone hammers and select a sturdier, less crumbly one (Visalberghi et al., 2009). (c) One male chimpanzee in Sweden’s Furuvik Zoo was observed every morning collecting stones into a neat little pile, which later in the day he used as ammunition to pelt visitors (Osvath & Karvonen, 2012). (d) Dolphins form coalitions, cooperatively hunt, and learn tool use from one another (Bearzi & Stanford, 2010). This bottlenose dolphin in Shark Bay, Western Australia, belongs to a small group that uses marine sponges as protective nose guards when probing the sea floor for fish (Krützen et al., 2005).

Using Tools and Transmitting Culture

Like humans, many other species invent behaviors and transmit cultural patterns to their peers and offspring (Boesch-

Researchers have found at least 39 local customs related to chimpanzee tool use, grooming, and courtship (Claidière & Whiten, 2012; Whiten & Boesch, 2001). One group may slurp termites directly from a stick, another group may pluck them off individually. One group may break nuts with a stone hammer, their neighbors with a wooden hammer. These group differences, along with differing communication and hunting styles, are the chimpanzee version of cultural diversity. Several experiments have brought chimpanzee cultural transmission into the laboratory (Horner et al., 2006). If Chimpanzee A obtains food either by sliding or by lifting a door, Chimpanzee B will then typically do the same to get food. And so will Chimpanzee C after observing Chimpanzee B. Across a chain of six animals, chimpanzees see, and chimpanzees do.

Other Cognitive Skills

A baboon knows everyone’s voice within its 80-

There is no question that other species display many remarkable cognitive skills. But one big question remains: Do they, like humans, exhibit language? In the next module, we’ll first consider what language is and how it develops.

What time is it now? When we asked you (in the section on overconfidence) to estimate how quickly you would finish this module, did you underestimate or overestimate?

Returning to our debate about how deserving we humans are of our name Homo sapiens, let’s pause to issue an interim report card. On decision making and risk assessment, our error-