28.2 Language Development

28-

Make a quick guess: How many words of your native language did you learn between your first birthday and your high school graduation? Although you use only 150 words for about half of what you say, you probably learned about 60,000 words (Bloom, 2000; McMurray, 2007). That averages (after age 2) to nearly 3500 words each year, or nearly 10 each day! How you did it—

Could you even state your language’s rules of syntax (the correct way to string words together to form sentences)? Most of us cannot. Yet before you were able to add 2 + 2, you were creating your own original and grammatically appropriate sentences. As a preschooler, you comprehended and spoke with a facility that puts to shame college students struggling to learn a foreign language.

We humans have an astonishing facility for language. With remarkable efficiency, we sample tens of thousands of words in our memory, effortlessly assemble them with near-

When Do We Learn Language?

Receptive LanguageChildren’s language development moves from simplicity to complexity. Infants start without language (in fantis means “not speaking”). Yet by 4 months of age, babies can recognize differences in speech sounds (Stager & Werker, 1997). They can also read lips: They prefer to look at a face that matches a sound, so we know they can recognize that ah comes from wide open lips and ee from a mouth with corners pulled back (Kuhl & Meltzoff, 1982). This marks the beginning of the development of babies’ receptive language, their ability to understand what is said to and about them. Infants’ language comprehension greatly outpaces their language production. Even at six months, long before speaking, many infants recognize object names (Bergelson & Swingley, 2012, 2013). At 7 months and beyond, babies grow in their power to do what you and I find difficult when listening to an unfamiliar language: to segment spoken sounds into individual words.

Productive LanguageLong after the beginnings of receptive language, babies’ productive language, their ability to produce words, matures. They recognize noun–

Before nurture molds babies’ speech, nature enables a wide range of possible sounds in the babbling stage, beginning at around 4 months. Many of these spontaneously uttered sounds are consonant-

By about 10 months old, infants’ babbling has changed so that a trained ear can identify the household language (de Boysson-

Around their first birthday, most children enter the one-word stage. They have already learned that sounds carry meanings, and if repeatedly trained to associate, say, fish with a picture of a fish, 1-

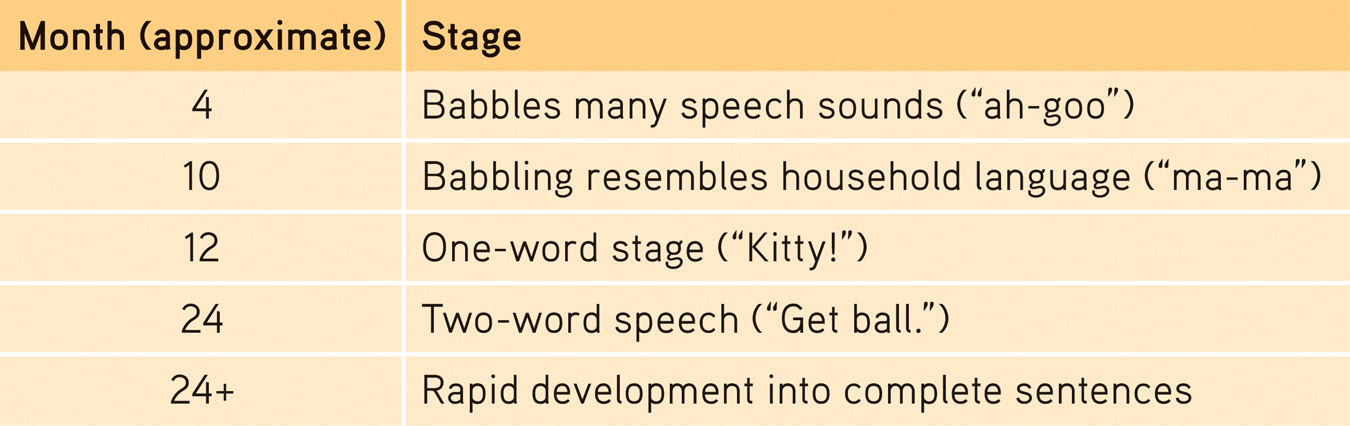

At about 18 months, children’s word learning explodes from about a word per week to a word per day. By their second birthday, most have entered the two-word stage (TABLE 28.1). They start uttering two-

Table 28.1

Table 28.1Summary of Language Development

Moving out of the two-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is the difference between receptive and productive language, and when do children normally hit these milestones in language development?

Infants normally start developing receptive language skills (ability to understand what is said to and about them) around 4 months of age. Then, starting with babbling at 4 months and beyond, infants normally start building productive language skills (ability to produce sounds and eventually words).

Explaining Language Development

The world’s 6000+ or so languages are structurally very diverse (Evans & Levinson, 2009). Linguist Noam Chomsky has argued that all languages nonetheless share some basic elements, which he calls universal grammar. All human languages, for example, have nouns, verbs, and adjectives as grammatical building blocks. Moreover, said Chomsky, we humans are born with a built-

We are not born with a built-

Statistical LearningWhen adults listen to an unfamiliar language, the syllables all run together. A young Sudanese couple new to North America and unfamiliar with English might, for example, hear United Nations as “Uneye Tednay Shuns.” Their 7-

In further testimony to infants’ surprising knack for soaking up language, research shows that 7-

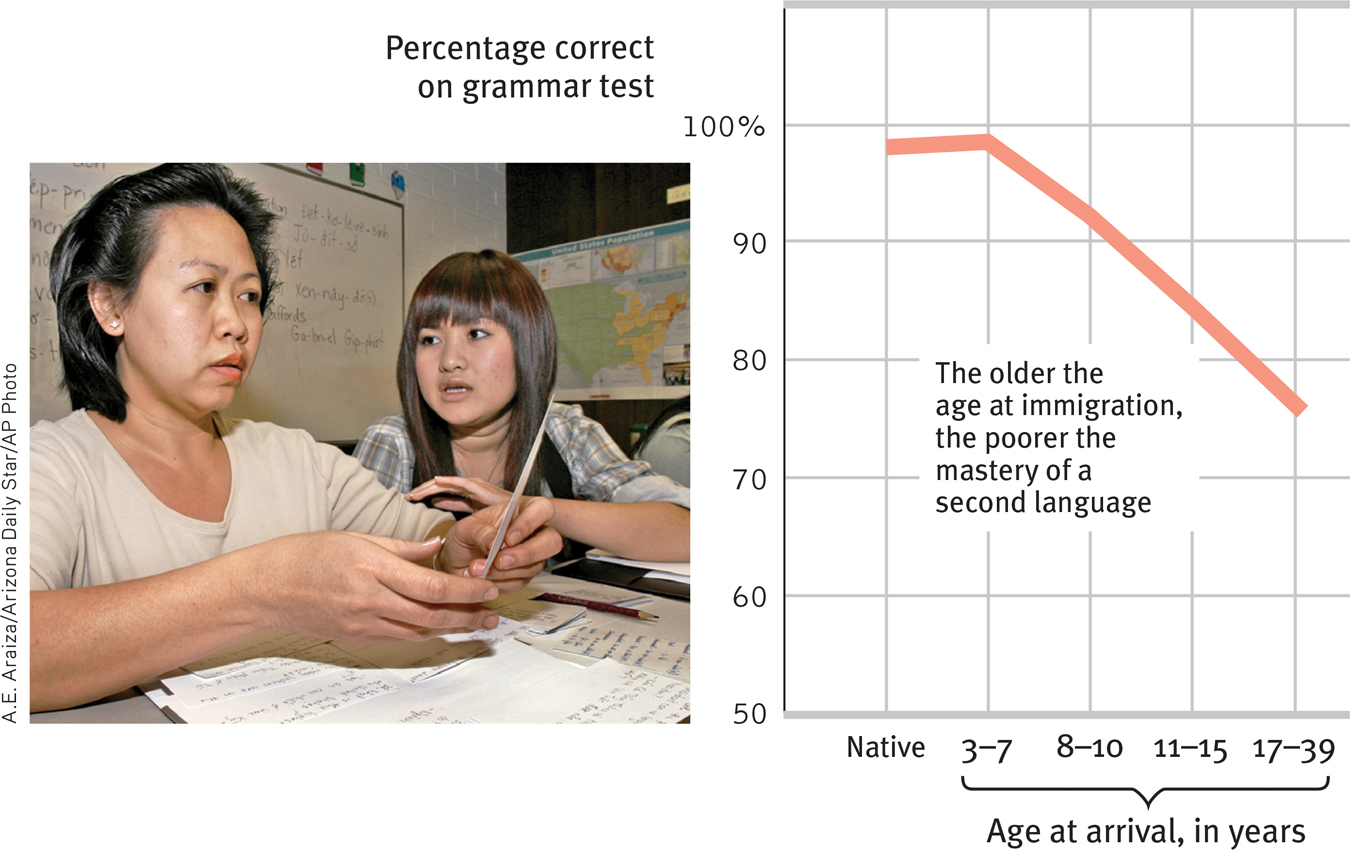

Critical PeriodsCould we train adults to perform this same feat of statistical analysis later in the human life span? Many researchers believe not. Childhood seems to represent a critical (or “sensitive”) period for mastering certain aspects of language before the language-

Figure 28.1

Figure 28.1Our ability to learn a new language diminishes with age Ten years after coming to the United States, Asian immigrants took an English grammar test. Although there is no sharply defined critical period for second language learning, those who arrived before age 8 understood American English grammar as well as native speakers did. Those who arrived later did not. (Data from Johnson & Newport, 1991.)

The window on language learning closes gradually in early childhood. Later-

Deafness and Language Development

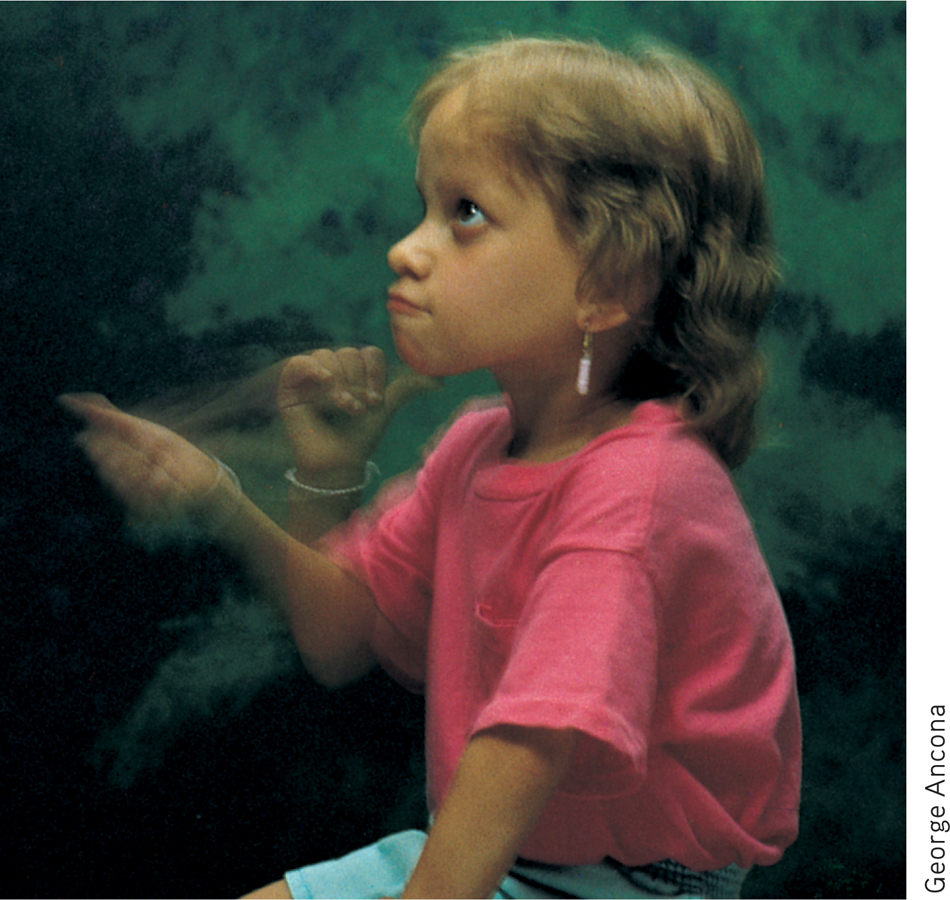

The impact of early experiences is evident in language learning in prelingually (before learning language) deaf1 children born to hearing-

“Childhood is the time for language, no doubt about it. Young children, the younger the better, are good at it; it is child’s play. It is a onetime gift to the species.”

Lewis Thomas, The Fragile Species, 1992

More than 90 percent of all deaf children are born to hearing parents. Most of these parents want their children to experience their world of sound and talk. Cochlear implants enable this by converting sounds into electrical signals and stimulating the auditory nerve by means of electrodes threaded into the child’s cochlea. But if an implant is to help children become proficient in oral communication, parents cannot delay the surgery until their child reaches the age of consent. Giving cochlear implants to children is hotly debated. Deaf culture advocates object to giving implants to children who were deaf prelingually. The National Association of the Deaf, for example, argues that deafness is not a disability because native signers are not linguistically disabled. More than five decades ago, Gallaudet University linguist William Stokoe (1960) showed that sign is a complete language with its own grammar, syntax, and meanings.

“Children can learn multiple languages without an accent and with good grammar, if they are exposed to the language before puberty. But after puberty, it’s very difficult to learn a second language so well. Similarly, when I first went to Japan, I was told not even to bother trying to bow, that there were something like a dozen different bows and I was always going to ‘bow with an accent’.”

Psychologist Stephen M. Kosslyn, “The World in the Brain,” 2008

Deaf culture advocates sometimes further contend that deafness could as well be considered “vision enhancement” as “hearing impairment.” Close your eyes and immediately you, too, will notice your attention being drawn to your other senses. In one experiment, people who had spent 90 minutes sitting quietly blindfolded became more accurate in their location of sounds (Lewald, 2007). When kissing, lovers minimize distraction and increase sensitivity by closing their eyes.

People who lose one channel of sensation compensate with a slight enhancement of their other sensory abilities (Backman & Dixon, 1992; Levy & Langer, 1992). Blind musicians are more likely than sighted ones to develop perfect pitch (Hamilton, 2000). Blind people are also more accurate than sighted people at locating a sound source with one ear plugged (Gougoux et al., 2005; Lessard et al., 1998). And when reading Braille—

In deaf cats, brain areas normally used for hearing donate themselves to the visual system (Lomber et al., 2010). So, too, in people who have been deaf from birth: They exhibit enhanced attention to their peripheral vision (Bavelier et al., 2006). Their auditory cortex, starved for sensory input, remains largely intact but becomes responsive to touch and to visual input (Karns et al., 2012). Once repurposed, the auditory cortex becomes less available for hearing—

Living in a Silent WorldWorldwide, 360 million people live with disabling hearing loss (WHO, 2013). Some are profoundly deaf; others (more men than women) have hearing loss (Agrawal et al., 2008). Some were deaf prelingually; others have known the hearing world. Some sign and identify with the language-

The challenges of life without hearing may be greatest for children. Unable to communicate in customary ways, signing playmates may struggle to coordinate their play with speaking playmates. School achievement may also suffer; academic subjects are rooted in spoken languages. Adolescents may feel socially excluded, with a resulting low self-

Adults whose hearing becomes impaired later in life also face challenges. When older people with hearing loss must expend effort to hear words, they have less remaining cognitive capacity available to remember and comprehend them (Wingfield et al., 2005). In several studies, people with hearing loss, especially those not wearing hearing aids, have reported feeling sadder, being less socially engaged, and more often experiencing others’ irritation (Chisolm et al., 2007; Fellinger et al., 2007; Kashubeck-

I [DM] understand. My mother, with whom we communicated by writing notes on an erasable “magic pad,” spent her last dozen years in an utterly silent world, largely withdrawn from the stress and strain of trying to interact with people outside a small circle of family and old friends. With my own hearing declining on a trajectory toward hers, I find myself sitting front and center at plays and meetings, seeking quiet corners in restaurants, and asking my wife to make necessary calls to friends whose accents differ from ours. I do benefit from cool technology (see www.hearingloop.org) that, at the press of a button, can transform my hearing aids into in-

As she aged, my mother came to feel that seeking social interaction was simply not worth the effort. I share newspaper columnist Kisor’s belief that communication is worth the effort (p. 246): “So, … I will grit my teeth and plunge ahead.” To reach out, to connect, to communicate with others, even across a chasm of silence, is to affirm our humanity as social creatures.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What was the premise of researcher Noam Chomsky’s work in language development?

Chomsky maintained that all languages share a universal grammar, and humans are biologically predisposed to learn the grammar rules of language.

- Why is it so difficult to learn a new language in adulthood?

Our brain’s critical period for language learning is in childhood, when we can absorb language structure almost effortlessly. As we move past that stage in our brain’s development, our ability to learn a new language diminishes dramatically.