30.1 Early and Modern Tests of Mental Abilities

30-

Some societies concern themselves with promoting the collective welfare of the family, community, and society. Other societies emphasize individual opportunity. Plato, a pioneer of the individualist tradition, wrote more than 2000 years ago in The Republic that “no two persons are born exactly alike; but each differs from the other in natural endowments, one being suited for one occupation and the other for another.” As heirs to Plato’s individualism, people in Western societies have pondered how and why individuals differ in mental ability.

Francis Galton: Belief in Hereditary Genius

Western attempts to assess such differences began in earnest with English scientist Francis Galton (1822–

Although Galton’s quest for a simple intelligence measure failed, he gave us some statistical techniques that we still use (as well as the phrase nature and nurture). And his persistent belief in the inheritance of genius—

Alfred Binet: Predicting School Achievement

Modern intelligence testing traces its birth to early twentieth-

In 1905, Binet and Simon first presented their work under the archaic title, “New Methods for Diagnosing the Idiot, the Imbecile, and the Moron” (Nicolas & Levine, 2012). They began by assuming that all children follow the same course of intellectual development but that some develop more rapidly. On tests, therefore, a “dull” child should score much like a typical younger child, and a “bright” child like a typical older child. Thus, their goal became measuring each child’s mental age, the level of performance typically associated with a certain chronological age. The average 9-

To measure mental age, Binet and Simon theorized that mental aptitude, like athletic aptitude, is a general capacity that shows up in various ways. They tested a variety of reasoning and problem-

“The IQ test was invented to predict academic performance, nothing else. If we wanted something that would predict life success, we’d have to invent another test completely.”

Social psychologist Robert Zajonc (1984b)

Binet and Simon made no assumptions concerning why a particular child was slow, average, or precocious. Binet personally leaned toward an environmental explanation. To raise the capacities of low-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What did Binet hope to achieve by establishing a child’s mental age?

Binet hoped that the child’s mental age (the age that typically corresponds to the child’s level of performance), would help identify appropriate school placements of children.

Lewis Terman: The Innate IQ

Binet’s fears were realized soon after his death in 1911, when others adapted his tests for use as a numerical measure of inherited intelligence. This began when Stanford University professor Lewis Terman (1877–

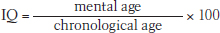

From such tests, German psychologist William Stern derived the famous intelligence quotient, or IQ. The IQ is simply a person’s mental age divided by chronological age and multiplied by 100 to get rid of the decimal point:

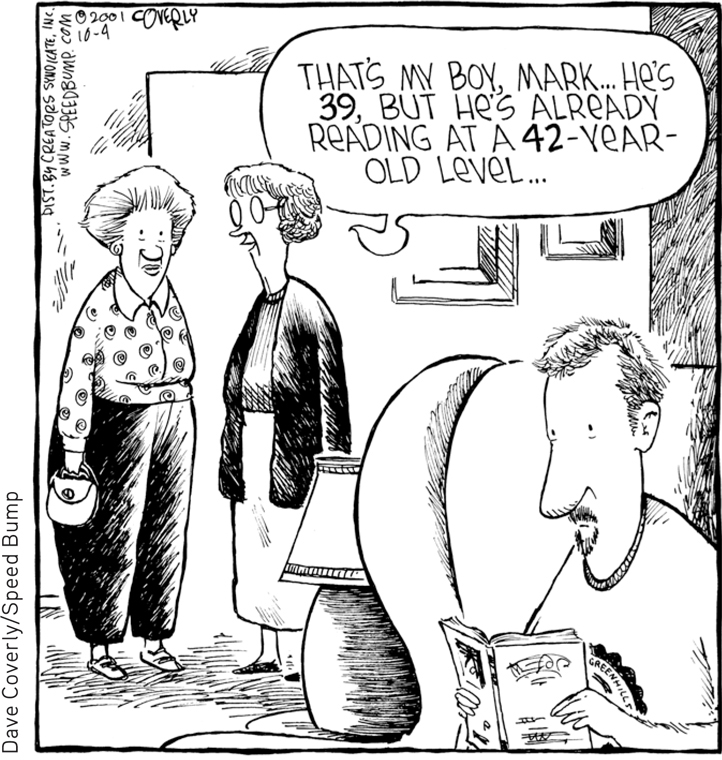

Thus, an average child, whose mental and chronological ages are the same, has an IQ of 100. But an 8-

The original IQ formula worked fairly well for children but not for adults. (Should a 40-

Terman (1916, p. 4) promoted the widespread use of intelligence testing to “take account of the inequalities of children in original endowment” by assessing their “vocational fitness.” In sympathy with Francis Galton’s eugenics—the much-

With Terman’s help, the U.S. government developed new tests to evaluate both newly arriving immigrants and World War I army recruits—

Binet probably would have been horrified that his test had been adapted and used to draw such conclusions. Indeed, such sweeping judgments became an embarrassment to most of those who championed testing. Even Terman came to appreciate that test scores reflected not only people’s innate mental abilities but also their education, native language, and familiarity with the culture assumed by the test. Abuses of the early intelligence tests serve to remind us that science can be value-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is the IQ of a 4-year-old with a mental age of 5?

125 (5 ÷ 4 × 100 = 125)

David Wechsler: Separate Scores for Separate Skills

Psychologist David Wechsler created what is now the most widely used individual intelligence test, the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), together with a version for school-

- Similarities—Reasoning the commonality of two objects or concepts, such as “In what way are wool and cotton alike?”

- Vocabulary—Naming pictured objects, or defining words (“What is a guitar?”)

- Block Design—Visual abstract processing, such as “Using the four blocks, make one just like this.”

- Letter-Number Sequencing—On hearing a series of numbers and letters, repeat the numbers in ascending order, and then the letters in alphabetical order: “R-2-C-1-M-3.”

The WAIS yields not only an overall intelligence score, as does the Stanford-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- An employer with a pool of applicants for a single available position is interested in testing each applicant’s potential. To help her decide whom she should hire, she should use an ______________ (achievement/aptitude) test. That same employer wishing to test the effectiveness of a new, on-the-job training program would be wise to use an ______________ (achievement/aptitude) test.

aptitude; achievement