32.1 Twin and Adoption Studies

32-

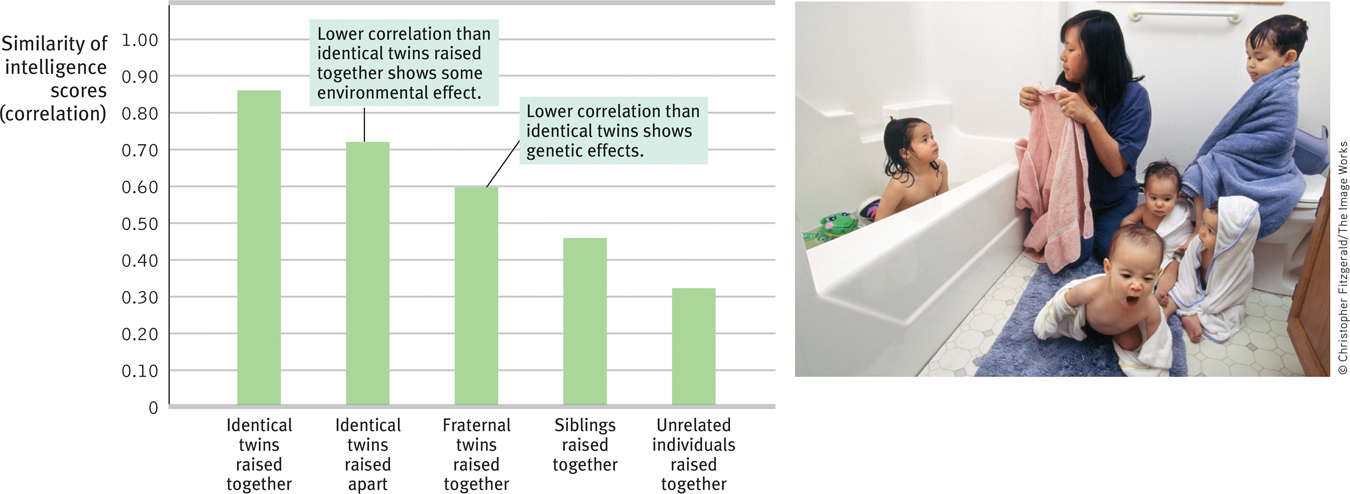

Do people who share the same genes also share mental abilities? As you can see from FIGURE 32.1, which summarizes many studies, the answer is clearly Yes. Consider:

- The intelligence test scores of identical twins raised together are nearly as similar as those of the same person taking the same test twice (Haworth et al., 2009; Lykken, 2006). (The scores of fraternal twins, who share only about half their genes, differ more.) Estimates of the heritability of intelligence—

the extent to which intelligence test score variation can be attributed to genetic variation— range from 50 to 80 percent (Calvin et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2009; Neisser et al., 1996). Identical twins also exhibit substantial similarity (and heritability) in specific talents, such as music, math, and sports, with heredity even accounting for more than half the variation in the national math and science exam scores of British 16- year- olds (Shakeshaft et al., 2013; Vinkhuyzen et al., 2009). - Scans reveal that identical twins’ brains have similar gray- and white-matter volume, and the areas associated with verbal and spatial intelligence are virtually the same (Deary et al., 2009; Thompson et al., 2001). Their brains also show similar activity while doing mental tasks (Koten et al., 2009).

- Are there known genes for genius? Today’s researchers have identified chromosomal regions important to intelligence, and they have pinpointed specific genes that seemingly influence variations in intelligence and learning disorders (Davies et al., 2011; Plomin et al., 2013). But efforts to isolate specific intelligence-influencing genes have not found any one mighty gene (Chabris et al., 2012). One worldwide team of more than 200 researchers pooled their data on the DNA and schooling of 126,559 people (Rietveld et al., 2013). No single DNA segment was more than a minuscule predictor of years of schooling, and together all the genetic variations they examined accounted for only about 2 percent of the schooling differences. After examining 21,151 people’s brain scans, the researchers were able to identify a gene variation that predicted a slightly bigger brain, which is a modest predictor of intelligence (Stein et al., 2012). The gene sleuthing continues, but this much seems clear: Intelligence is polygenetic, involving many genes. Wendy Johnson (2010) likens it to height: 54 specific gene variations together have accounted for 5 percent of our individual differences in height, leaving the rest yet to be discovered. For height as for intelligence, what matters is the combination of many genes.

Other evidence points to environment effects:

- Where environments vary widely, as they do among children of less-educated parents, environmental differences are more predictive of intelligence scores (Rowe et al., 1999; Tucker-Drob et al., 2011; Turkheimer et al., 2003).

- Studies also show that adoption enhances the intelligence scores of mistreated or neglected children (van IJzendoorn & Juffer, 2005, 2006). So does adoption from poverty into middle-class homes (Nisbett et al., 2012).

- The intelligence scores of “virtual twins”—same-age, unrelated siblings adopted as infants and raised together—correlate +.28 (Segal et al., 2012). This suggests a modest influence of their shared environment.

Figure 32.1

Figure 32.1Intelligence: Nature and nurture The most genetically similar people have the most similar intelligence scores. Remember: 1.0 indicates a perfect correlation; zero indicates no correlation at all. (Data from McGue et al., 1993.)

407

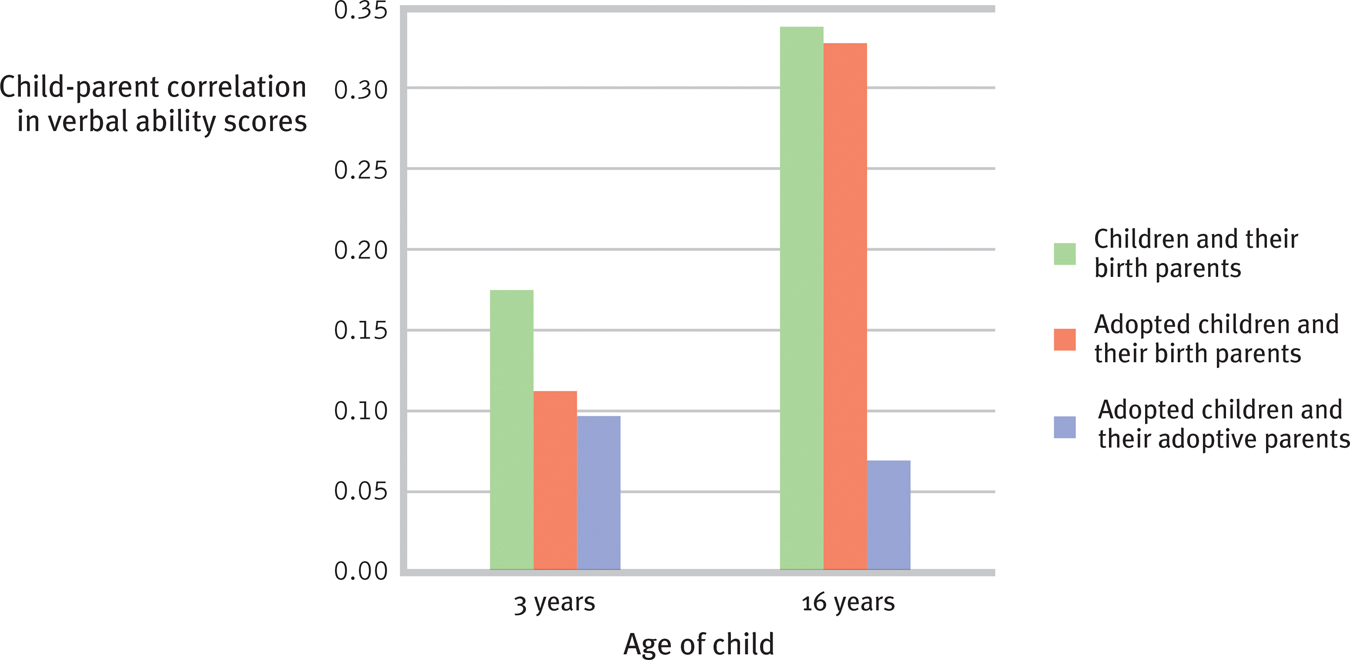

Seeking to disentangle genes and environment, researchers have also compared the intelligence test scores of adopted children with those of (a) their biological parents (the providers of their genes) and (b) their adoptive parents (the providers of their home environment). Over time, adopted children accumulate experience in their differing adoptive families. So would you expect the family-

If you would, behavior geneticists have a stunning surprise for you. Mental similarities between adopted children and their adoptive families wane with age, until the correlation approaches zero by adulthood (McGue et al., 1993). Genetic influences—

Figure 32.2

Figure 32.2In verbal ability, who do adopted children resemble? As the years went by in their adoptive families, children’s verbal ability scores became more like their biological parents’ scores. (Data from Plomin & DeFries, 1998.)

408

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- A check on your understanding of heritability: If environments become more equal, the heritability of intelligence would

- increase.

- decrease.

- be unchanged.

a. (Heritability–