34.2 The Psychology of Hunger

34-

Our internal hunger games are indeed pushed by our physiological state—

Taste Preferences: Biology and Culture

Body chemistry and environmental factors together influence not only the when of hunger, but also the what—

Our preferences for sweet and salty tastes are genetic and universal. Other taste preferences are conditioned, as when people given highly salted foods develop a liking for excess salt (Beauchamp, 1987), or when people who have been sickened by a food develop an aversion to it. (The frequency of children’s illnesses provides many chances for them to learn food aversions.)

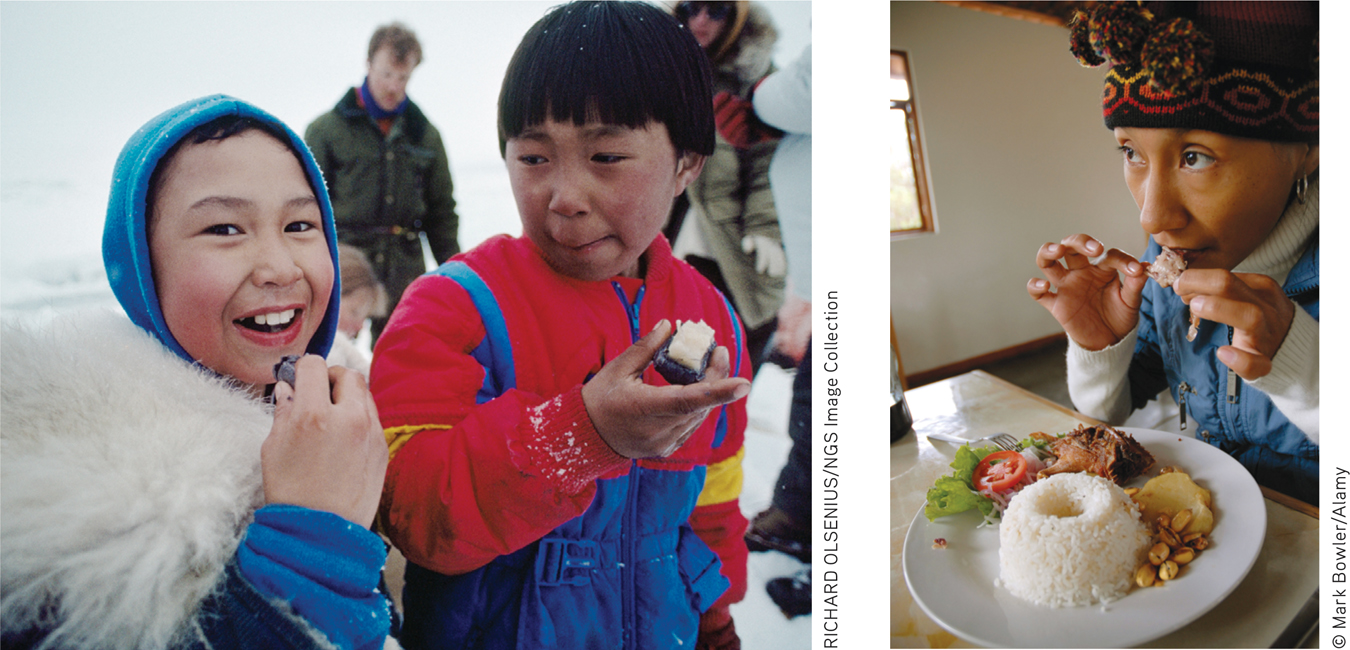

Culture affects taste, too. Bedouins enjoy eating the eye of a camel, which most North Americans would find repulsive. Many Japanese people enjoy nattó, a fermented soybean dish that “smells like the marriage of ammonia and a tire fire,” reports smell expert Rachel Herz (2012). Although many Westerners find this disgusting, Asians, she adds, are often repulsed by what Westerners love—

Rats tend to avoid unfamiliar foods (Sclafani, 1995). So do we, especially animal-

Other taste preferences also are adaptive. For example, the spices most commonly used in hot-

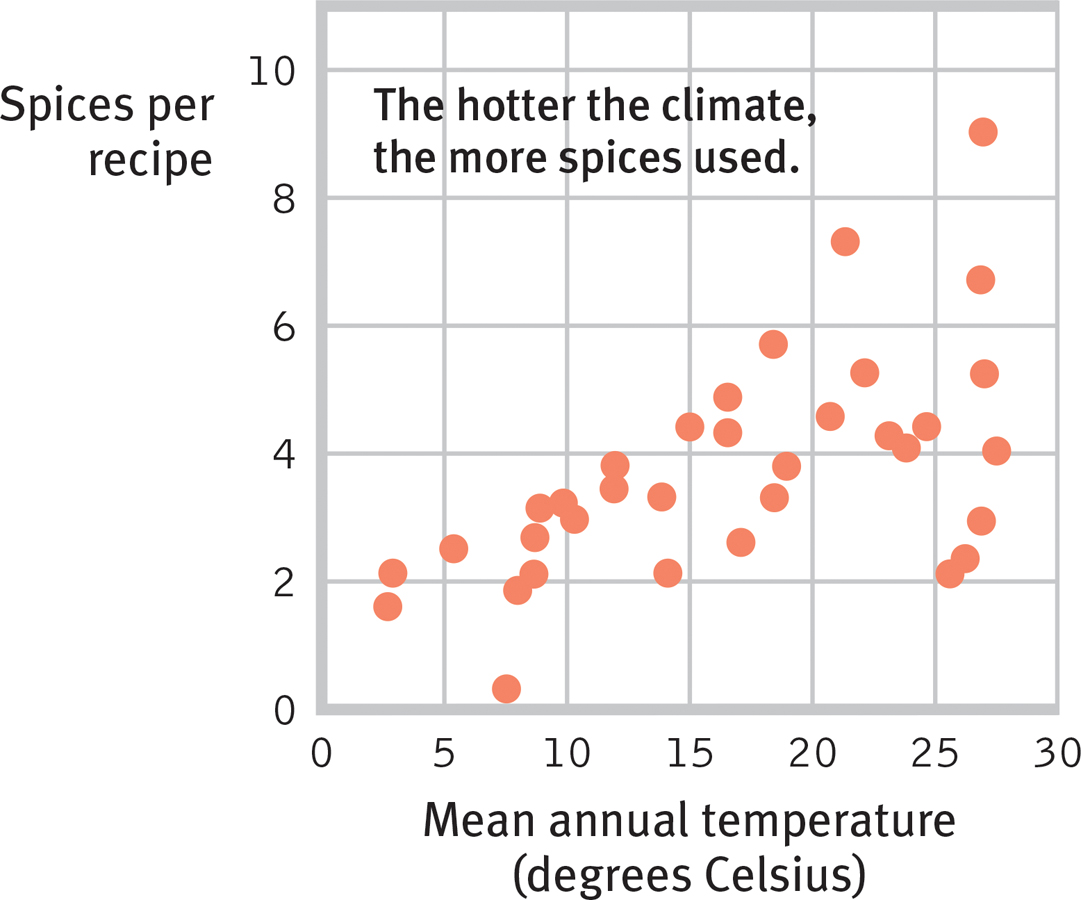

Figure 34.4

Figure 34.4Hot cultures like hot spices Countries with hot climates, in which food historically spoiled more quickly, feature recipes with more bacteria-

Situational Influences on Eating

To a surprising extent, situations also control our eating—

- Do you eat more when eating with others? Most of us do (Herman et al., 2003; Hetherington et al., 2006). After a party, you may realize you’ve overeaten. This happens because the presence of others tends to amplify our natural behavior tendencies. (We explore this social facilitation in the Social Psychology modules.)

Consider how researchers test some of these ideas with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Larger Dinner Plates Make People Fat? - Unit bias occurs with similar mindlessness. At France’s National Center for Scientific Research, Andrew Geier and his colleagues (2006) wondered why French waistlines are smaller than American waistlines. From soda drinks to yogurt sizes, the French offer foods in smaller portion sizes. Does it matter? (One could as well order two small sandwiches as one large one.) To find out, the investigators offered people varieties of free snacks. For example, in the lobby of an apartment house, they laid out either full or half pretzels, big or little Tootsie Rolls, or a big bowl of M&M’s with either a small or large serving scoop. Their consistent result: Offered a supersized standard portion, people put away more calories. In another study, people offered pasta ate more when given a big plate (Van Ittersum & Wansink, 2012). Children also eat more when using adult-sized (rather than child-sized) dishware (DiSantis et al., 2013). Even nutrition experts helped themselves to 31 percent more ice cream when given a big bowl rather than a small one, and 15 percent more when scooping with a big rather than a small scoop (Wansink, 2006, 2007). People pour more into and drink more from short, wide than tall, narrow glasses. And they take more of easier-to-reach food on buffet lines (Marteau et al., 2012). Portion size matters.

- Food variety also stimulates eating. Offered a dessert buffet, we eat more than we do when choosing a portion from one favorite dessert. For our early ancestors, variety was healthy. When foods were abundant and varied, eating more provided a wide range of vitamins and minerals and produced fat that protected them during winter cold or famine. When a bounty of varied foods was unavailable, eating less extended the food supply until winter or famine ended (Polivy et al., 2008; Remick et al., 2009).

For a 7-minute video review of hunger, see LaunchPad’s Video: Hunger and Eating.

For a 7-minute video review of hunger, see LaunchPad’s Video: Hunger and Eating.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- After an eight-hour hike without food, your long-awaited favorite dish is placed in front of you, and your mouth waters in anticipation. Why?

You have learned to respond to the sight and aroma that signal the food about to enter your mouth. Both physiological cues (low blood sugar) and psychological cues (anticipation of the tasty meal) heighten your experienced hunger.