34.3 Obesity and Weight Control

34-

Obesity can be socially toxic, by affecting both how you are treated and how you feel about yourself. Obesity has been associated with lower psychological well-

The Physiology of Obesity

Our bodies store fat for good reason. Fat is an ideal form of stored energy—

In parts of the world where food and sweets are now abundantly available, the rule that once served our hungry distant ancestors—

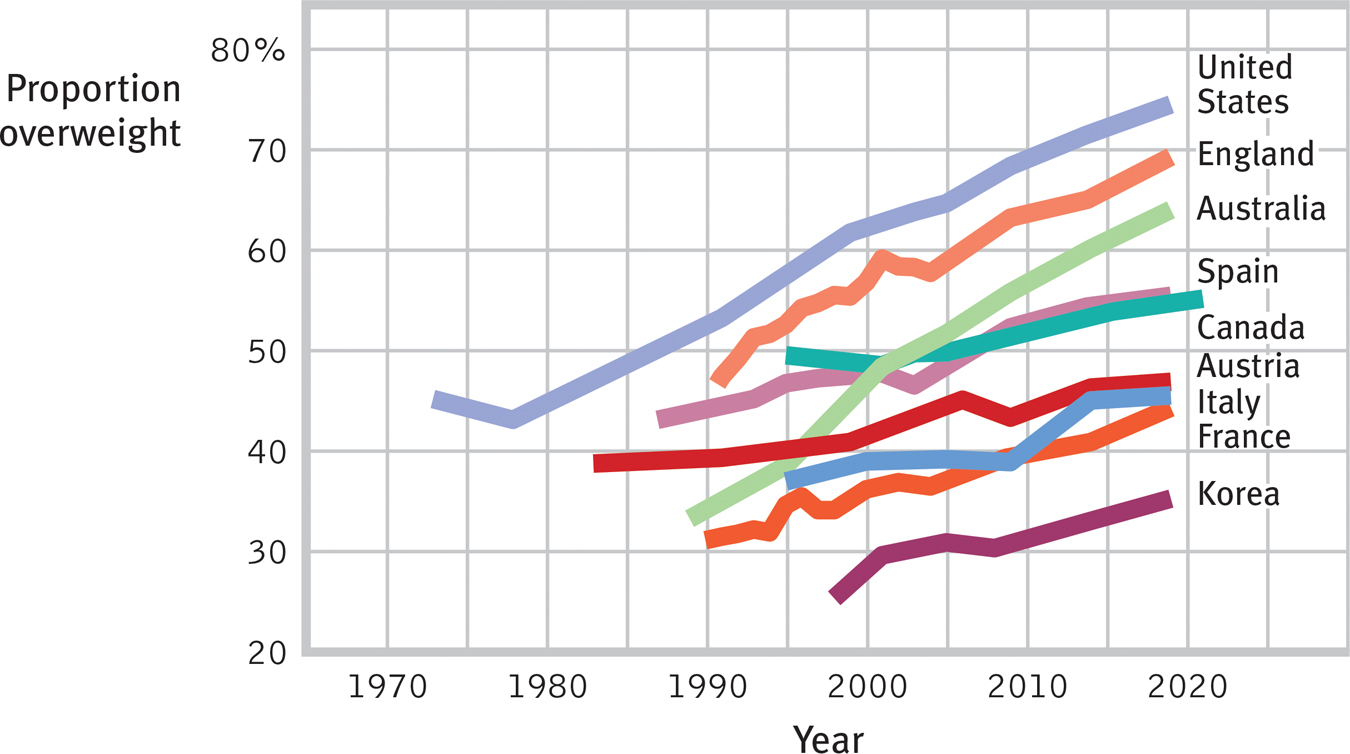

- between 1980 and 2013 the proportion of overweight adults increased from 29 to 37 percent among the world’s men, and from 30 to 38 percent among women.

- over the last 33 years, no country has reduced its obesity rate. Not one.

- national variations are huge, with the percentage overweight ranging from 85 percent in Tonga to 3 percent in Timor-Leste.

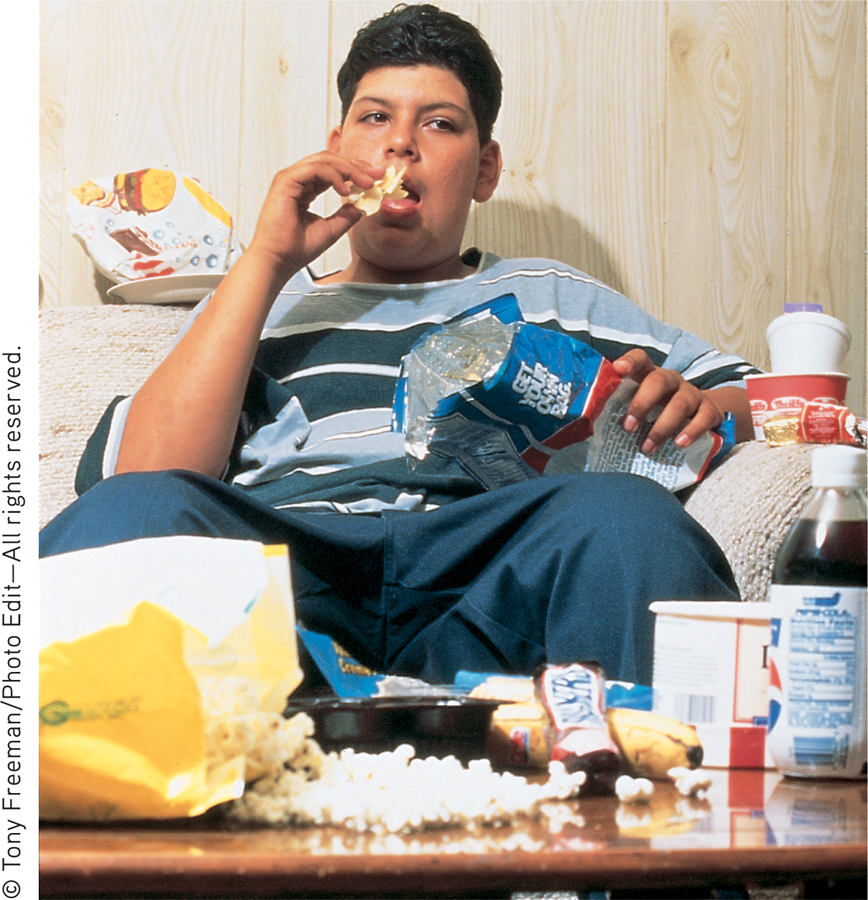

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an overweight person has a body mass index (BMI) of 25 or more; someone obese has a BMI of 30 or more. (See www.tinyurl.com/GiveMyBMI to calculate your BMI and to see where you are in relation to others in your country and in the world.) In the United States, the adult obesity rate has more than doubled in the last 40 years, reaching 36 percent, and child-

American men, on average, say they weigh 196 pounds and women say they weigh 160 pounds. Both figures are nearly 20 pounds heavier than in 1990.”

Elizabeth Mendes, www.gallup.com, 2011

In one digest of 97 studies of 2.9 million people, being simply overweight was not a health risk, while being obese was (Flegal et al., 2013). Fitness matters more than being a little overweight. But significant obesity increases the risk of diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, gallstones, arthritis, and certain types of cancer, thus increasing health care costs and shortening life expectancy (de Gonzales et al., 2010; Jarrett et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2009). Extreme obesity increases risk of suicidal behaviors (Wagner et al., 2013). Research also has linked women’s obesity to their risk of late-

Set Point and MetabolismResearch on the physiology of obesity challenges the stereotype of severely overweight people being weak-

Lean people also seem naturally disposed to move about. They burn more calories than do energy-

The Genetic FactorDo our genes predispose us to eat more or less? To burn more calories by fidgeting or fewer by sitting still? Studies confirm a genetic influence on body weight. Consider two examples:

- Despite shared family meals, adoptive siblings’ body weights are uncorrelated with one another or with those of their adoptive parents. Rather, people’s weights resemble those of their biological parents (Grilo & Pogue-Geile, 1991).

- Identical twins have closely similar weights, even when raised apart (Hjelmborg et al., 2008; Plomin et al., 1997). Across studies, their weight correlates +.74. The much lower +.32 correlation among fraternal twins suggests that genes explain two-thirds of our varying body mass (Maes et al., 1997).

The Food and Activity FactorsGenes tell an important part of the obesity story. But environmental factors are mighty important, too.

Studies in Europe, Japan, and the United States show that children and adults who suffer from sleep loss are more vulnerable to obesity (Keith et al., 2006; Nedeltcheva et al., 2010; Taheri, 2004a,b). With sleep deprivation, the levels of leptin (which reports body fat to the brain) fall, and ghrelin (the appetite-

Social influence is another factor. One 32-

“We put fast food on every corner, we put junk food in our schools, we got rid of [physical education classes], we put candy and soda at the checkout stand of every retail outlet you can think of. The results are in. It worked.”

Harold Goldstein, Executive Director of the California Center for Public Health Advocacy, 2009, when imagining a vast U.S. national experiment to encourage weight gain

The strongest evidence that environment influences weight comes from our fattening world (FIGURE 34.5). What explains this growing problem? Changing food consumption and activity levels are at work. We are eating more and moving less, with lifestyles sometimes approaching those of animal feedlots (where farmers fatten inactive animals). In the United States, jobs requiring moderate physical activity declined from about 50 percent in 1960 to 20 percent in 2011 (Church et al., 2011). Worldwide, 31 percent of adults (including 43 percent of Americans and 25 percent of Europeans) are now sedentary, which means they average less than 20 minutes per day of moderate activity such as walking (Hallal et al., 2012). Sedentary occupations increase the chance of being overweight, as 86 percent of U.S. truck drivers reportedly are (Jacobson et al., 2007).

Figure 34.5

Figure 34.5Past and projected overweight rates, by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

The “bottom” line: New stadiums, theaters, and subway cars—

These findings reinforce an important finding from psychology’s study of intelligence: There can be high levels of heritability (genetic influence on individual differences) without heredity explaining group differences. Genes mostly determine why one person today is heavier than another. Environment mostly determines why people today are heavier than their counterparts 50 years ago. Our eating behavior also demonstrates the now-

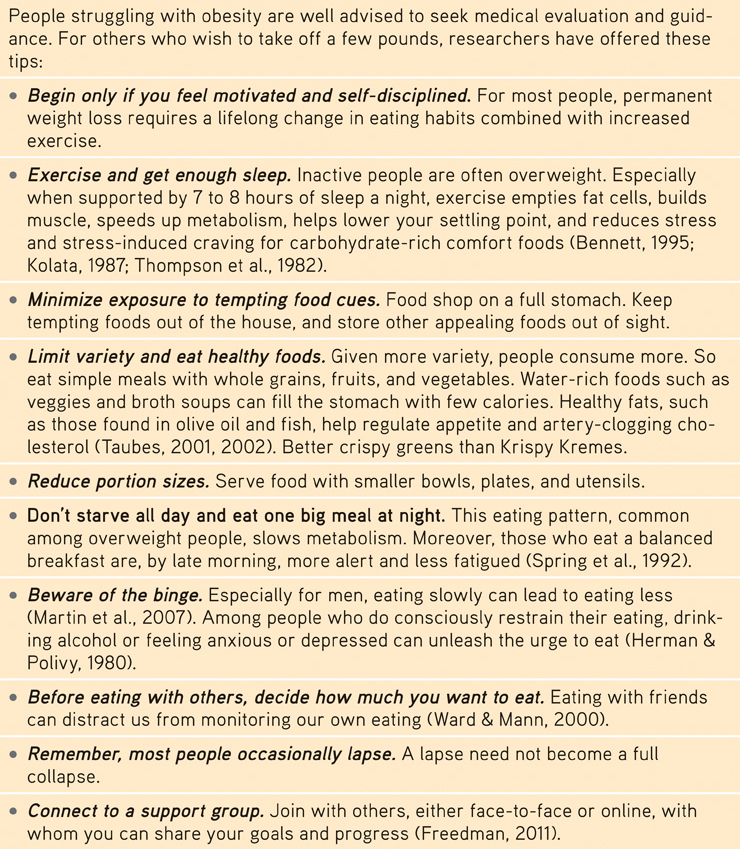

Table 34.1

Table 34.1Waist Management

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Why can two people of the same height, age, and activity level maintain the same weight, even if one of them eats much less than the other does?

Individuals have very different set points and genetically influenced metabolism levels, causing them to burn calories differently.