35.3 Sexual Orientation

In one British survey, of the 18,876 people contacted, 1 percent were asexual, having “never felt sexually attracted to anyone at all” (Bogaert, 2004, 2006b; 2012). People identifying as asexual are, however, nearly as likely as others to report masturbating, noting that it feels good, reduces anxiety, or “cleans out the plumbing.”

35-

To motivate is to energize and direct behavior. So far, we have considered the energizing of sexual motivation but not its direction, which is our sexual orientation—our enduring sexual attraction toward members of our own sex (homosexual orientation), the other sex (heterosexual orientation), or both sexes (bisexual orientation). We experience this attraction in our interests, thoughts, and fantasies (who’s that person in your imagination?). Cultures vary in their attitudes toward same-

Sexual Orientation: The Numbers

How many people are exclusively homosexual? About 10 percent, as the popular press has often assumed? Or 20 percent, as the average American estimated in a 2013 survey (Jones et al., 2014)? According to more than a dozen national surveys that have explored sexual orientation in Europe and the United States, a better estimate is about 3 or 4 percent of men and 2 percent of women (Chandra et al., 2011; Herbenick et al., 2010a; Savin-

Survey methods that absolutely guarantee people’s anonymity reveal another percent or two of gay people (Coffman et al., 2013). Moreover, people in less tolerant places are more likely to hide their sexual orientation. About 3 percent of California men express a same-

Fewer than 1 percent of people—

What does it feel like to be homosexual in a heterosexual culture? If you are heterosexual, one way to understand is to imagine how you would feel if you were socially isolated for openly admitting or displaying your feelings toward someone of the other sex. How would you react if you overheard people making crude jokes about heterosexual people, or if most movies, TV shows, and advertisements portrayed (or implied) homosexuality? And how would you answer if your family members were pleading with you to change your heterosexual lifestyle and to enter into a homosexual marriage?

Facing such reactions, some individuals struggle with their sexual attractions, especially during adolescence and if feeling rejected by parents or harassed by peers. If lacking social support, the result may be lower self-

Today’s psychologists therefore view sexual orientation as neither willfully chosen nor willfully changed. “Efforts to change sexual orientation are unlikely to be successful and involve some risk of harm,” declared a 2009 American Psychological Association report. Sexual orientation in some ways is like handedness: Most people are one way, some the other. A very few are truly ambidextrous. Regardless, the way one is endures.

This conclusion is most strongly established for men. Women’s sexual orientation tends to be less strongly felt and potentially more fluid and changing (Chivers, 2005; Diamond, 2008; Dickson et al., 2013). In general, men are sexually simpler. Their lesser sexual variability is apparent in many ways, notes Roy Baumeister (2000). Across time, across cultures, across situations, and across differing levels of education, religious observance, and peer influence, adult women’s sexual drive and interests are more flexible and varying than are adult men’s. Women, for example, more often prefer to alternate periods of high sexual activity with periods of almost none (Mosher et al., 2005). In their pupil dilation and genital responses to erotic videos, and in their implicit attitudes, heterosexual women exhibit more bisexual attraction than do men (Rieger & Savin-

In men, a high sex drive is associated with increased attraction to women (if heterosexual), or men (if homosexual). In women, a high sex drive is generally associated with increased attraction to both men and women (Lippa, 2006, 2007a; Lippa et al., 2010). When shown sexually explicit film clips, men’s genital and subjective sexual arousal is mostly to preferred sexual stimuli (for heterosexual viewers, depictions of women). Women respond more nonspecifically to depictions of sexual activity involving males or females (Chivers et al., 2007).

Is there truth to the homosexual-

Origins of Sexual Orientation

Note that the scientific question is not “What causes homosexuality?” (or “What causes heterosexuality?”) but “What causes differing sexual orientations?” In pursuit of answers, psychological science compares the backgrounds and physiology of people whose sexual orientations differ.

So, our sexual orientation is something we do not choose and (especially for males) cannot change. Where, then, do these preferences come from? See if you can anticipate the conclusions that have emerged from hundreds of research studies by responding Yes or No to the following questions:

- Is homosexuality linked with problems in a child’s relationships with parents, such as with a domineering mother and an ineffectual father, or a possessive mother and a hostile father?

- Does homosexuality involve a fear or hatred of people of the other sex, leading individuals to direct their desires toward members of their own sex?

- Is sexual orientation linked with levels of sex hormones currently in the blood?

- As children, were most homosexuals molested, seduced, or otherwise sexually victimized by an adult homosexual?

The answer to all these questions has been No (Storms, 1983). In a search for possible environmental influences on sexual orientation, Kinsey Institute investigators interviewed nearly 1000 homosexuals and 500 heterosexuals. They assessed nearly every imaginable psychological cause of homosexuality—

And consider this: If “distant fathers” were more likely to produce homosexual sons, then shouldn’t boys growing up in father-

So, what else might influence sexual orientation? One theory has proposed that people develop same-

The bottom line from a half-

Same-

Gay-

It should not surprise us that in other ways, too, brains differ with sexual orientation (Bao & Swaab, 2011; Savic & Lindström, 2008). Remember our maxim: Everything psychological is simultaneously biological. But when do such brain differences begin? At conception? In the womb? During childhood or adolescence? Does experience produce these differences? Or is it genes or prenatal hormones (or genes via prenatal hormones)?

LeVay does not view the hypothalamus as a sexual orientation center; rather, he sees it as an important part of the neural pathway engaged in sexual behavior. He acknowledges that sexual behavior patterns may influence the brain’s anatomy. In fish, birds, rats, and humans, brain structures vary with experience—

“Gay men simply don’t have the brain cells to be attracted to women.”

Simon LeVay, The Sexual Brain, 1993

Responses to hormone-

Genetic InfluencesEvidence indicates a genetic influence on sexual orientation. “First, homosexuality does appear to run in families,” noted Brian Mustanski and Michael Bailey (2003). “Second, twin studies have established that genes play a substantial role in explaining individual differences in sexual orientation.” Identical twins are somewhat more likely than fraternal twins to share a homosexual orientation (Alanko et al., 2010; Lángström et al., 2008, 2010). (Because sexual orientations differ in many identical twin pairs, especially female twins, we know that other factors besides genes are also at work.)

By genetic manipulations, experimenters have created female fruit flies that during courtship act like males (pursuing other females) and males that act like females (Demir & Dickson, 2005). “We have shown that a single gene in the fruit fly is sufficient to determine all aspects of the flies’ sexual orientation and behavior,” explained Barry Dickson (2005). With humans, it’s likely that multiple genes, possibly in interaction with other influences, shape sexual orientation. A genome-

Researchers have speculated about possible reasons why “gay genes” might exist in the human gene pool, given that same-

A fertile females theory offers further support for the idea that maternal genetics may be at work (Bocklandt et al., 2006). Recent Italian studies confirm what others have found—

Prenatal InfluencesElevated rates of homosexual orientation in identical and fraternal twins suggest the influence not only of shared genes but also a shared prenatal environment. In animals and some human cases, prenatal hormone conditions have altered a fetus’ sexual orientation. German researcher Gunter Dorner (1976, 1988) pioneered research on the influence of prenatal hormones by manipulating a fetal rat’s exposure to male hormones, thereby “inverting” its sexual orientation. In other studies, when pregnant sheep were injected with testosterone during a critical period of fetal development, their female offspring later showed homosexual behavior (Money, 1987).

A critical period for the human brain’s neural-

“Modern scientific research indicates that sexual orientation is … partly determined by genetics, but more specifically by hormonal activity in the womb.”

Glenn Wilson and Qazi Rahman, Born Gay: The Psychobiology of Sex Orientation, 2005

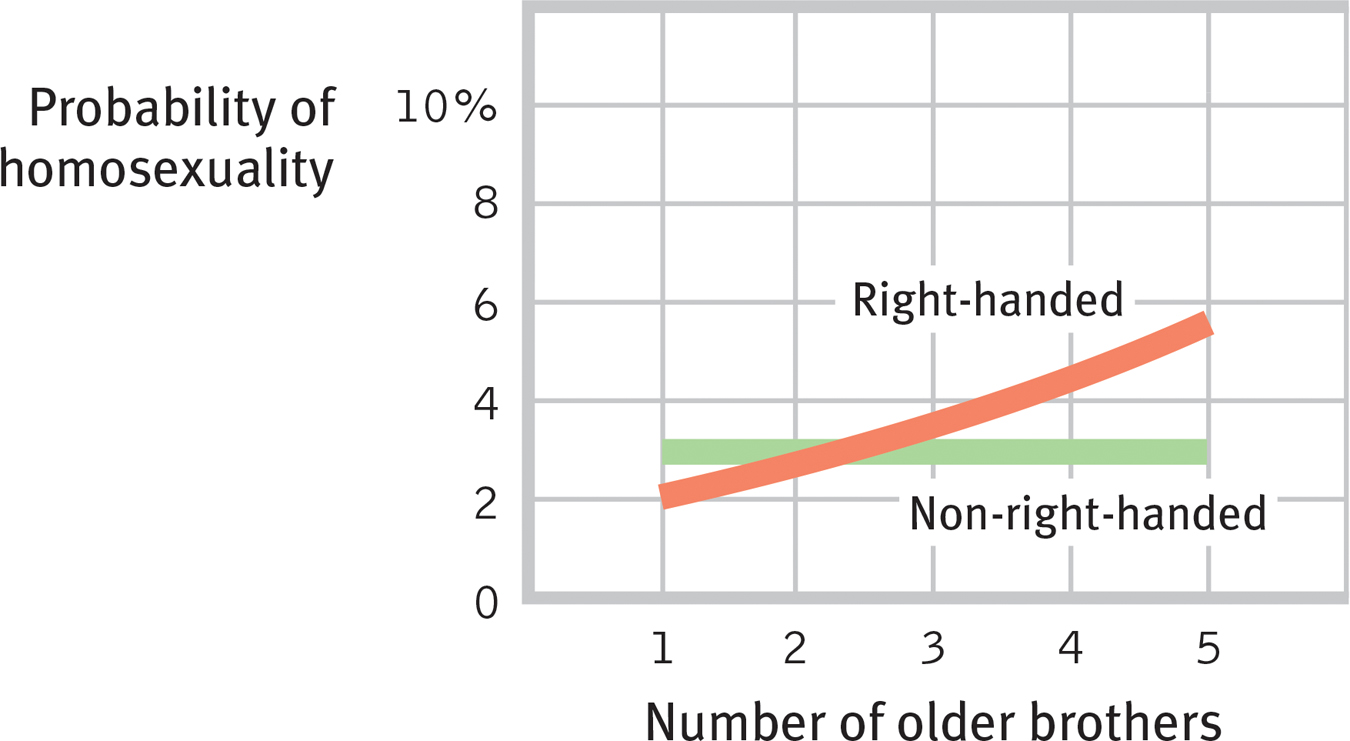

The mother’s immune system may also play a role in the development of sexual orientation. Men who have older brothers are somewhat more likely to be gay, report Ray Blanchard (2004, 2008a,b, 2014) and Anthony Bogaert (2003)—about one-

Figure 35.2

Figure 35.2The fraternal birth-

Gay-Straight Trait Differences

For an 8-minute overview of the biology of sexual orientation, see LaunchPad’s Video: Homosexuality and the Nature-Nurture Debate.

For an 8-minute overview of the biology of sexual orientation, see LaunchPad’s Video: Homosexuality and the Nature-Nurture Debate.

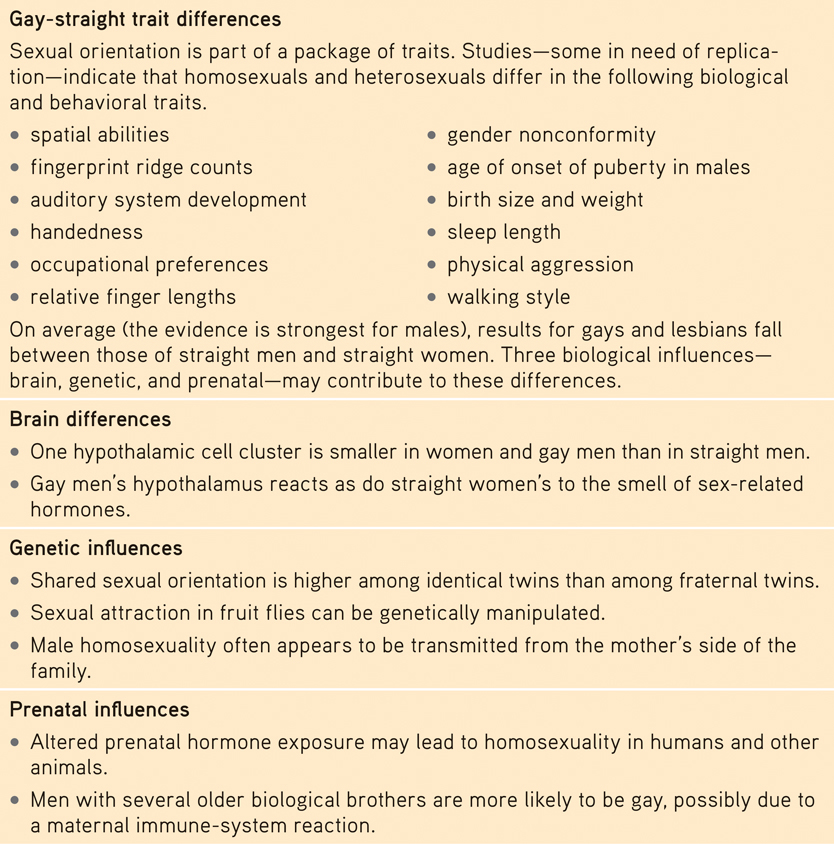

On several traits, gays and lesbians appear to fall midway between straight females and males (TABLE 35.1; see also LeVay, 2011; Rahman & Koerting, 2008). For example, lesbians’ cochlea and hearing systems develop in a way that is intermediate between those of heterosexual females and heterosexual males, which seems attributable to prenatal hormonal influence (McFadden, 2002). Gay men tend to be shorter and lighter, even at birth, than straight men, while women in same-

Table 35.1

Table 35.1Biological Correlates of Sexual Orientation

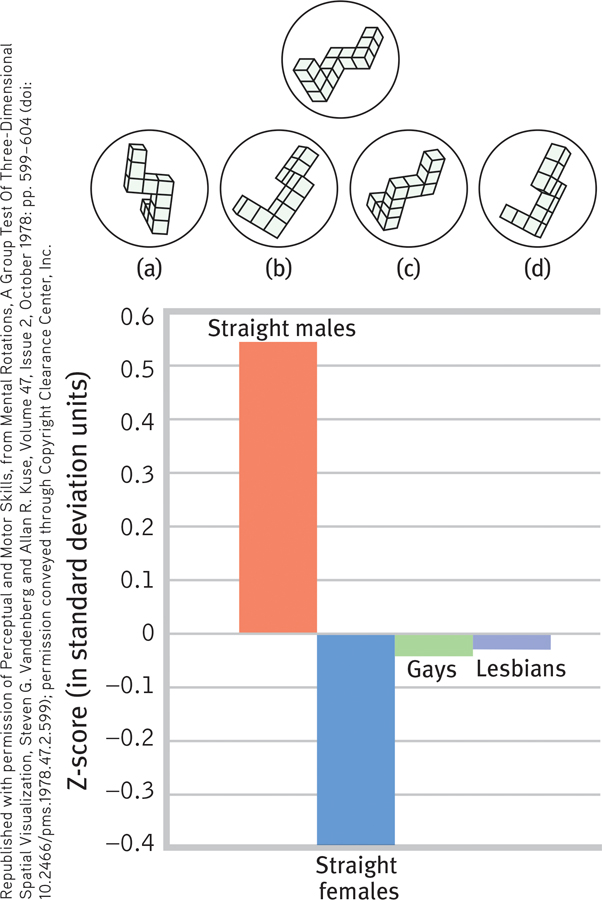

Another you-

Figure 35.3

Figure 35.3Spatial abilities and sexual orientation

Which of the four figures can be rotated to match the target figure at the top? Straight males tend to find this an easier task than do straight females, with gays and lesbians intermediate. (From Rahman et al., 2003, with 60 people tested in each group.)

Answer: Figures a and d.

***

The consistency of the brain, genetic, and prenatal findings has swung the pendulum toward a biological explanation of sexual orientation (Rahman & Wilson, 2003; Rahman & Koerting, 2008). Still, some people wonder: Should the cause of sexual orientation matter? Perhaps it shouldn’t, but people’s assumptions matter. To justify his signing a 2014 bill that made some homosexual acts punishable by life in prison, the president of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni, declared that homosexuality is not inborn but rather is a matter of “choice” (Balter, 2014; Landau et al., 2014).

“There is no sound scientific evidence that sexual orientation can be changed.”

UK Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2009

However, the new biological research is a double-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Which THREE of the following five factors have researchers found to have an effect on sexual orientation?

- A domineering mother

- Size of certain cell clusters in the hypothalamus

- Prenatal hormone exposure

- A distant or ineffectual father

- For men, having multiple older biological brothers

b., c., e.