36.2 Achievement Motivation

36-

The biological perspective on motivation—

Think of someone you know who strives to succeed by excelling at any task where evaluation is possible. Now think of someone who is less driven. Psychologist Henry Murray (1938) defined the first person’s achievement motivation as a desire for significant accomplishment, for mastering skills or ideas, for control, and for attaining a high standard.

“Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration.”

Thomas Edison (1847–1931)

Thanks to their persistence and eagerness for challenge, people with high achievement motivation do achieve more. One study followed the lives of 1528 California children whose intelligence test scores were in the top 1 percent. Forty years later, when researchers compared those who were most and least successful professionally, they found a motivational difference. Those most successful were more ambitious, energetic, and persistent. As children, they had more active hobbies. As adults, they participated in more groups and sports (Goleman, 1980). Gifted children are able learners. Accomplished adults are tenacious doers. Most of us are energetic doers when starting and when finishing a project. It’s easiest—

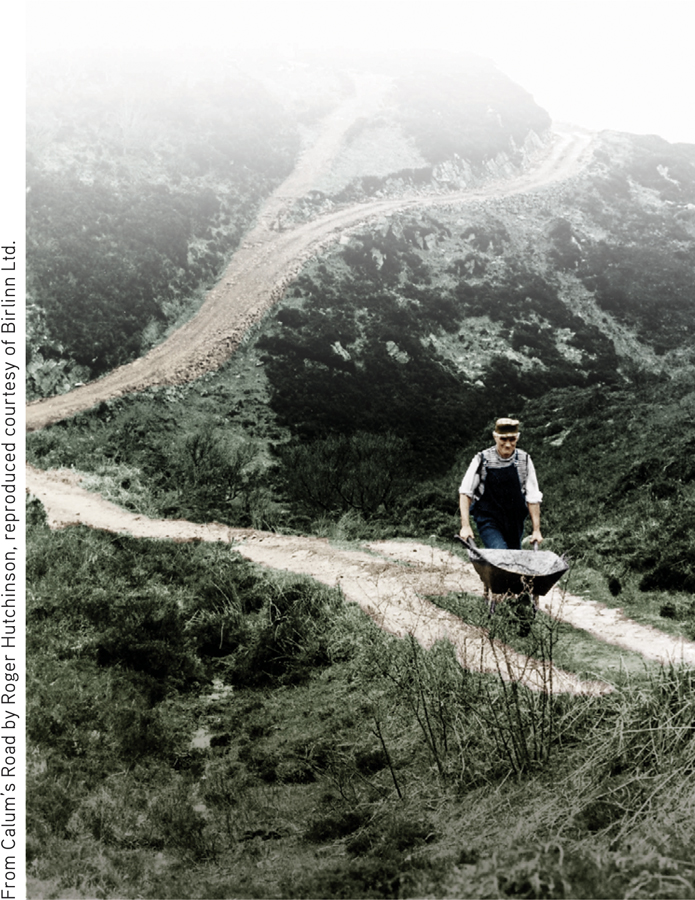

“With a road,” a former neighbor explained, “he hoped new generations of people would return to the north end of Raasay,” restoring its culture (Hutchinson, 2006). Day after day he worked through rough hillsides, along hazardous cliff faces, and over peat bogs. Finally, 10 years later, he completed his supreme achievement. The road, which the government has since surfaced, remains a visible example of what vision plus determined grit can accomplish. It bids us each to ponder: What “roads”—what achievements-

In other studies of both secondary school and university students, self-

Discipline refines talent. By their early twenties, top violinists have accumulated thousands of lifetime practice hours—

Duckworth and Seligman have a name for this passionate dedication to an ambitious, long-

Although intelligence is distributed like a bell curve, achievements are not. That tells us that achievement involves much more than raw ability. That is why organizational psychologists seek ways to engage and motivate ordinary people doing ordinary jobs (see Appendix A: Psychology at Work). And that is why training students in “hardiness”—resilience under stress—

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What have researchers found an even better predictor of school performance than intelligence test scores?

self-