37.1 Emotion: Arousal, Behavior, and Cognition

Not only emotion, but most psychological phenomena (vision, sleep, memory, sex, and so forth) can be approached these three ways—physiologically, behaviorally, and cognitively.

37-

AS MY [DM’S] PANICKED SEARCH for Peter illustrates, emotions are a mix of

- bodily arousal (heart pounding).

- expressive behaviors (quickened pace).

- conscious experience, including thoughts (“Is this a kidnapping?”) and feelings (panic, fear, joy).

The puzzle for psychologists is figuring out how these three pieces fit together. To do that, we need answers to two big questions:

- A chicken-and-egg debate: Does your bodily arousal come before or after your emotional feelings? (Did I first notice my racing heart and faster step, and then feel terror about losing Peter? Or did my sense of fear come first, stirring my heart and legs to respond?)

- How do thinking (cognition) and feeling interact? Does cognition always come before emotion? (Did I think about a kidnapping threat before I reacted emotionally?)

Historical emotion theories, as well as current research, have sought to answer these questions.

Historical Emotion Theories

James-

Cannon-

If our bodily responses and emotional experiences occur simultaneously and one does not affect the other, as Cannon and Bard believed, then people who suffer spinal cord injuries should not notice a difference in their experience of emotion after the injury. But there are differences, according to one study of 25 World War II soldiers (Hohmann, 1966). Those with lower-

But most researchers now agree that our emotions also involve cognition (Averill, 1993; Barrett, 2006). Whether we fear the man behind us on the dark street depends entirely on whether we interpret his actions as threatening or friendly.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- According to the Cannon-Bard theory, (a) our physiological response to a stimulus (for example, a pounding heart), and (b) the emotion we experience (for example, fear) occur __________ (simultaneously/sequentially). According to the James-Lange theory, (a) and (b) occur _________ (simultaneously/sequentially).

simultaneously; sequentially (first the physiological response, and then the experienced emotion)

Schachter and Singer Two-Factor Theory: Arousal + Label = Emotion

37-

Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer (1962) believed that an emotional experience requires a conscious interpretation of arousal: Our physical reactions and our thoughts (perceptions, memories, and interpretations) together create emotion. In their two-factor theory, emotions therefore have two ingredients: physical arousal and cognitive appraisal.

Consider how arousal spills over from one event to the next. Imagine arriving home after an invigorating run and finding a message that you got a longed-

To explore this spillover effect, Schachter and Singer injected college men with the hormone epinephrine, which triggers feelings of arousal. Picture yourself as a participant: After receiving the injection, you go to a waiting room, where you find yourself with another person (actually an accomplice of the experimenters) who is acting either euphoric or irritated. As you observe this person, you begin to feel your heart race, your body flush, and your breathing become more rapid. If you had been told to expect these effects from the injection, what would you feel? The actual volunteers felt little emotion—

This discovery—

The point to remember: Arousal fuels emotion; cognition channels it.

For a 4-minute demonstration of the relationship between arousal and cognition, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Emotion = Arousal Plus Interpretation.

For a 4-minute demonstration of the relationship between arousal and cognition, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Emotion = Arousal Plus Interpretation.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- According to Schachter and Singer, two factors lead to our experience of an emotion: (1) physiological arousal and (2) ____________ appraisal.

cognitive

Zajonc, LeDoux, and Lazarus: Does Cognition Always Precede Emotion?

But is the heart always subject to the mind? Must we always interpret our arousal before we can experience an emotion? Robert Zajonc (1923–

For example, when people repeatedly view stimuli flashed too briefly for them to interpret, they come to prefer those stimuli. Unaware of having previously seen them, they nevertheless like them. We have an acutely sensitive automatic radar for emotionally significant information, such that even a subliminally flashed stimulus can prime us to feel better or worse about a follow-

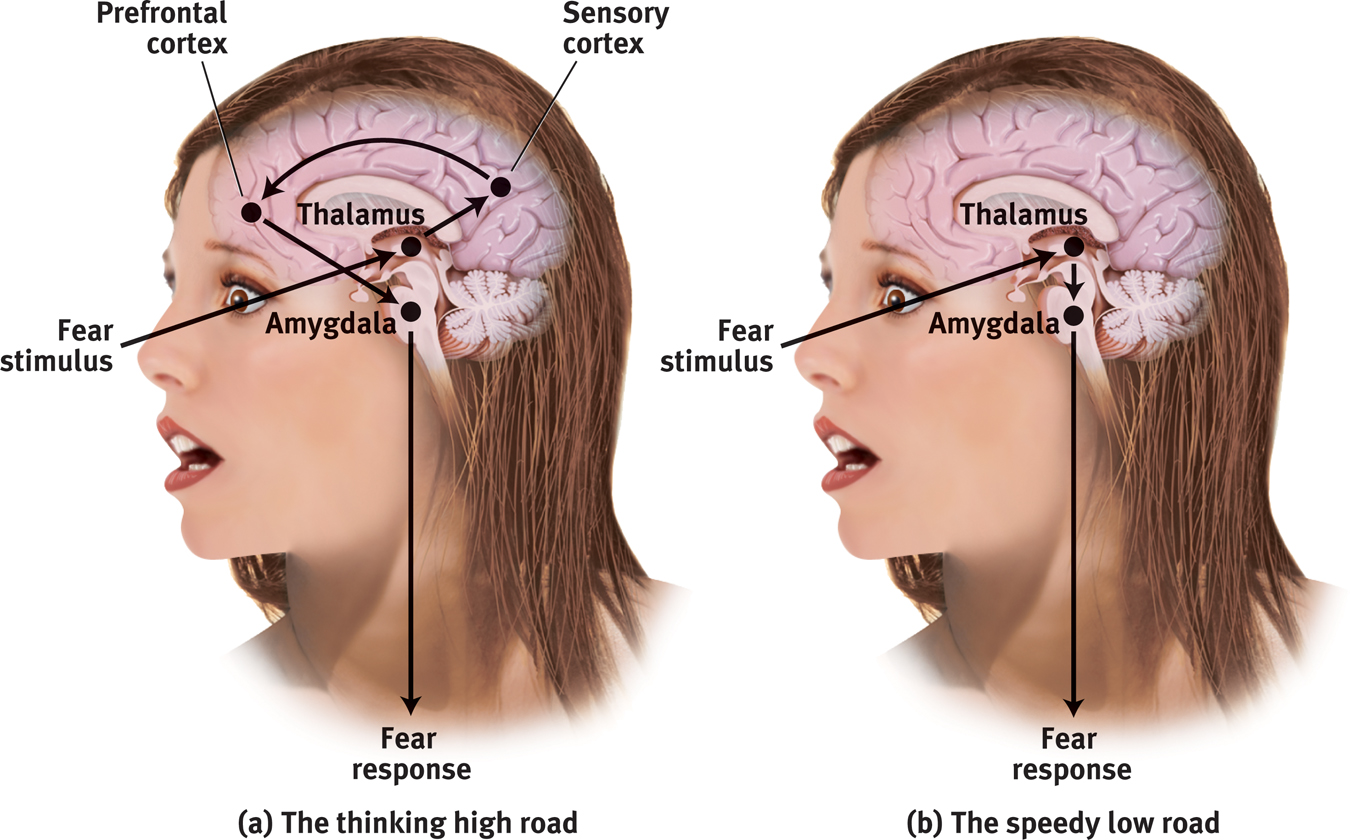

Neuroscientists are charting the neural pathways of emotions (Ochsner et al., 2009). Our emotional responses can follow two different brain pathways. Some emotions (especially more complex feelings like hatred and love) travel a “high road.” A stimulus following this path would travel (by way of the thalamus) to the brain’s cortex (FIGURE 37.1a). There, it would be analyzed and labeled before the response command is sent out, via the amygdala (an emotion-

Figure 37.1

Figure 37.1The brain’s pathways for emotions In the two-

But sometimes our emotions (especially simple likes, dislikes, and fears) take what Joseph LeDoux (2002) has called the “low road,” a neural shortcut that bypasses the cortex. Following the low road, a fear-

The amygdala sends more neural projections up to the cortex than it receives back, which makes it easier for our feelings to hijack our thinking than for our thinking to rule our feelings (LeDoux & Armony, 1999). Thus, in the forest, we can jump at the sound of rustling bushes nearby, leaving it to our cortex to decide later whether the sound was made by a snake or by the wind. Such experiences support Zajonc’s belief that some of our emotional reactions involve no deliberate thinking.

Emotion researcher Richard Lazarus (1991, 1998) conceded that our brain processes vast amounts of information without our conscious awareness, and that some emotional responses do not require conscious thinking. Much of our emotional life operates via the automatic, speedy low road. But, he asked, how would we know what we are reacting to if we did not in some way appraise the situation? The appraisal may be effortless and we may not be conscious of it, but it is still a mental function. To know whether a stimulus is good or bad, the brain must have some idea of what it is (Storbeck et al., 2006). Thus, said Lazarus, emotions arise when we appraise an event as harmless or dangerous, whether we truly know it is or not. We appraise the sound of the rustling bushes as the presence of a threat. Later, we realize that it was “just the wind.”

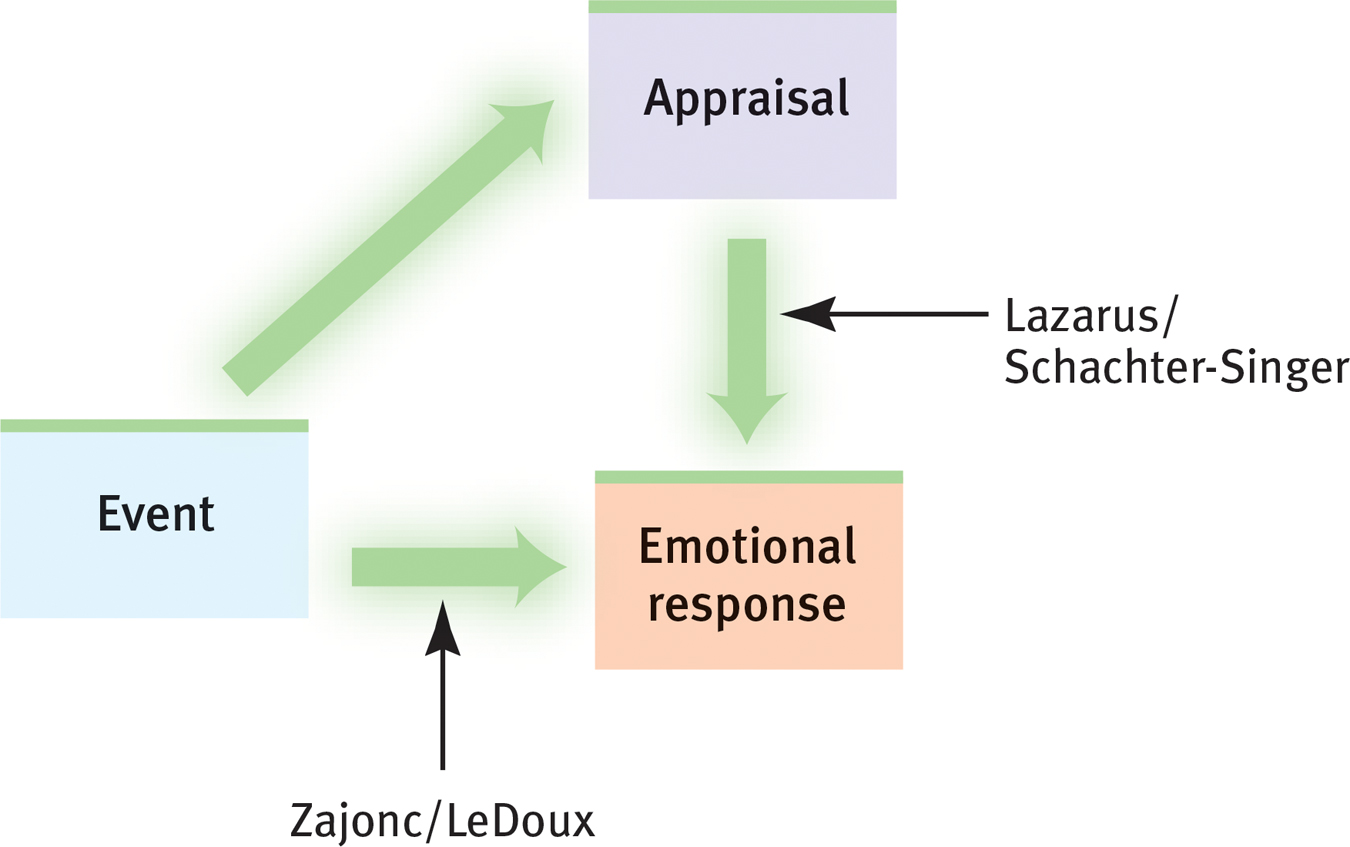

So, as Zajonc and LeDoux have demonstrated, some emotional responses—

Figure 37.2

Figure 37.2Two pathways for emotions Zajonc and LeDoux emphasized that some emotional responses are immediate, before any conscious appraisal. Lazarus, Schachter, and Singer emphasized that our appraisal and labeling of events also determine our emotional responses.

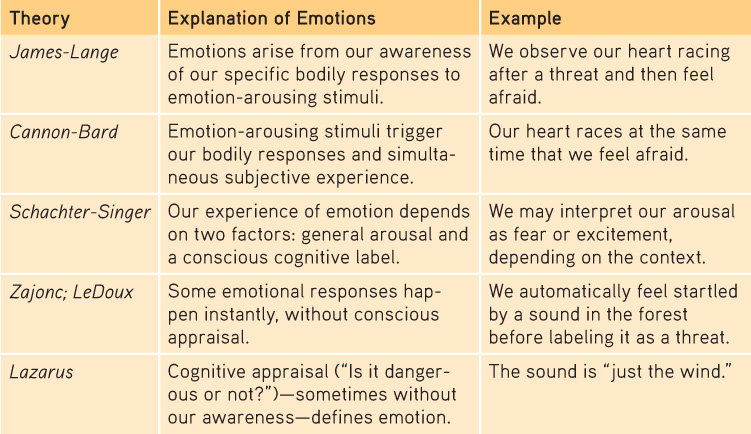

But our feelings about politics are also subject to our memories, expectations, and interpretations, as Lazarus, Schachter, and Singer might have predicted. Moreover, highly emotional people are intense partly because of their interpretations. They may personalize events as being somehow directed at them, and they may generalize their experiences by blowing single incidents out of proportion (Larsen & Diener, 1987). Thus, learning to think more positively can help people feel better. Although the emotional low road functions automatically, the thinking high road allows us to retake some control over our emotional life. Together, automatic emotion and conscious thinking weave the fabric of our emotional lives. (TABLE 37.1 summarizes these emotion theories.)

Table 37.1

Table 37.1Summary of Emotion Theories

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Emotion researchers have disagreed about whether emotional responses occur in the absence of cognitive processing. How would you characterize the approach of each of the following researchers: Zajonc, LeDoux, Lazarus, Schachter, and Singer?

Zajonc and LeDoux suggested that we experience some emotions without any conscious, cognitive appraisal. Lazarus, Schachter, and Singer emphasized the importance of appraisal and cognitive labeling in our experience of emotion.