39.1 Anger

39-

Anger, the sages have said, is “a short madness” (Horace, 65-

When we face a threat or challenge, fear triggers flight but anger triggers fight—

Anger can harm us: Chronic hostility is linked to heart disease. Anger boosts our heart rate, causes our skin to drip with sweat, and raises our testosterone levels (Herrero et al., 2010; Kubo et al., 2012; Peterson & Harmon-

Individualist cultures encourage people to vent their rage. Such advice is seldom heard in cultures where people’s identity is centered more on the group. People who keenly sense their interdependence see anger as a threat to group harmony (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). In Tahiti, for instance, people learn to be considerate and gentle. In Japan, from infancy on, angry expressions are less common than in Western cultures, where in recent politics, anger seems all the rage.

The Western vent-

- they direct their counterattack toward the provoker.

- their retaliation seems justifiable.

- their target is not intimidating.

In short, expressing anger can be temporarily calming if it does not leave us feeling guilty or anxious. But despite this temporary afterglow, catharsis usually fails to cleanse our rage. More often, expressing anger breeds more anger. For one thing, it may provoke further retaliation, causing a minor conflict to escalate into a major confrontation. For another, expressing anger can magnify anger. As behavior feedback research demonstrates, acting angry can make us feel angrier (Flack, 2006; Snodgrass et al., 1986). Anger’s backfire potential appeared in a study of 100 frustrated engineers and technicians just laid off by an aerospace company (Ebbesen et al., 1975). Researchers asked some workers questions that released hostility, such as, “What instances can you think of where the company has not been fair with you?” After expressing their anger, the workers later filled out a questionnaire that assessed their attitudes toward the company. Had the opportunity to “drain off” their hostility reduced it? Quite the contrary. These people expressed more hostility than those who had discussed neutral topics.

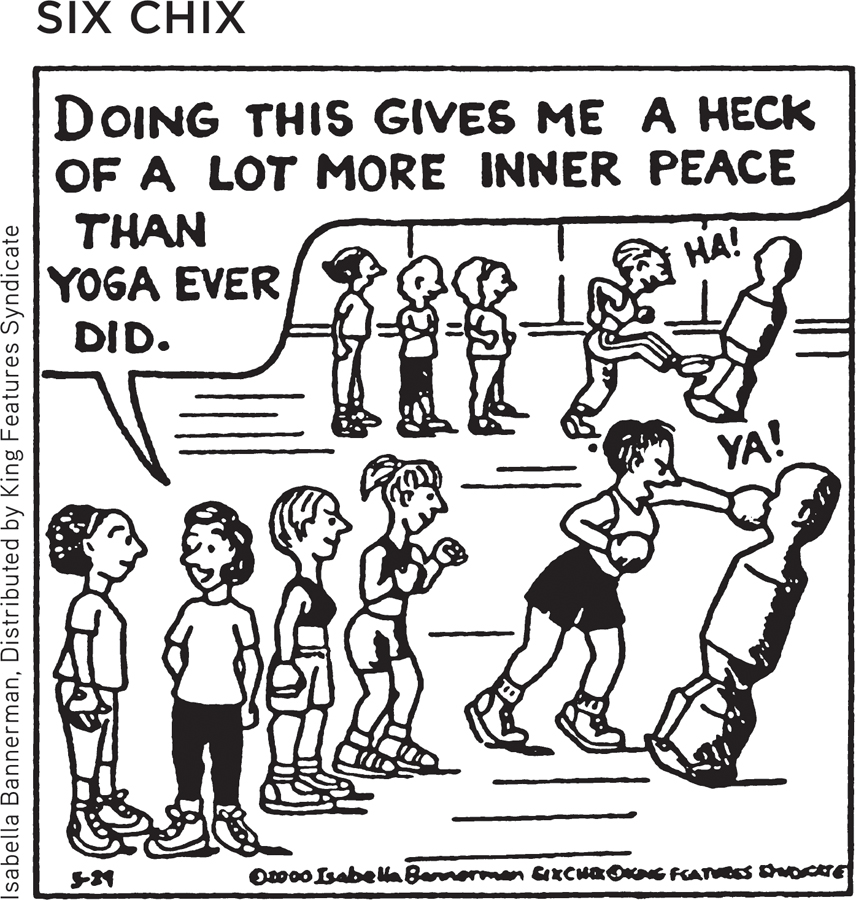

In another study, people who had been provoked were asked to wallop a punching bag while ruminating about the person who had angered them. Later, when given a chance for revenge, they became even more aggressive. “Venting to reduce anger is like using gasoline to put out a fire,” concluded the researcher (Bushman, 2002).

When anger fuels physically or verbally aggressive acts we later regret, it becomes maladaptive. Anger primes prejudice. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Americans who responded with anger more than fear displayed intolerance for immigrants and Muslims (DeSteno et al., 2004; Skitka et al., 2004). Angry outbursts that temporarily calm us are dangerous in another way: They may be reinforcing and therefore habit forming. If stressed managers find they can drain off some of their tension by berating an employee, then the next time they feel irritated and tense they may be more likely to explode again. Think about it: The next time you are angry you are likely to repeat whatever relieved (and reinforced) your anger in the past.

What is the best way to manage your anger? Experts offer three suggestions:

- Wait. You can reduce the level of physiological arousal of anger by waiting. “It is true of the body as of arrows,” noted Carol Tavris (1982), “what goes up must come down. Any emotional arousal will simmer down if you just wait long enough.”

- Find a healthy distraction or support. Calm yourself by exercising, playing an instrument, or talking things through with a friend. Brain scans show that ruminating inwardly about why you are angry serves only to increase amygdala blood flow (Fabiansson et al., 2012).

- Distance yourself. Try to move away from the situation mentally, as if you are watching it unfold from a distance. Self-distancing reduces rumination, anger, and aggression (Kross & Ayduk, 2011; Mischkowski et al., 2012).

“Anger will never disappear so long as thoughts of resentment are cherished in the mind.”

The Buddha, 500 b.c.e.

Anger is not always wrong. Used wisely, it can communicate strength and competence (Tiedens, 2001). Anger also motivates people to take action and achieve goals (Aarts et al., 2010). Controlled expressions of anger are more adaptive than either hostile outbursts or pent-

What if someone’s behavior really hurts you, and you cannot resolve the conflict? Research commends the age-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Which one of the following is an effective strategy for reducing angry feelings?

- Retaliate verbally or physically.

- Wait or “simmer down.”

- Express anger in action or fantasy.

- Review the grievance silently.

b