3.1 The Scientific Method

3-

In everyday conversation, we often use theory to mean “mere hunch.” Someone might, for example, discount evolution as “only a theory”—as if it were mere speculation. In science, a theory explains behaviors or events by offering ideas that organize what we have observed. By organizing isolated facts, a theory simplifies. By linking facts with deeper principles, a theory offers a useful summary. As we connect the observed dots, a coherent picture emerges.

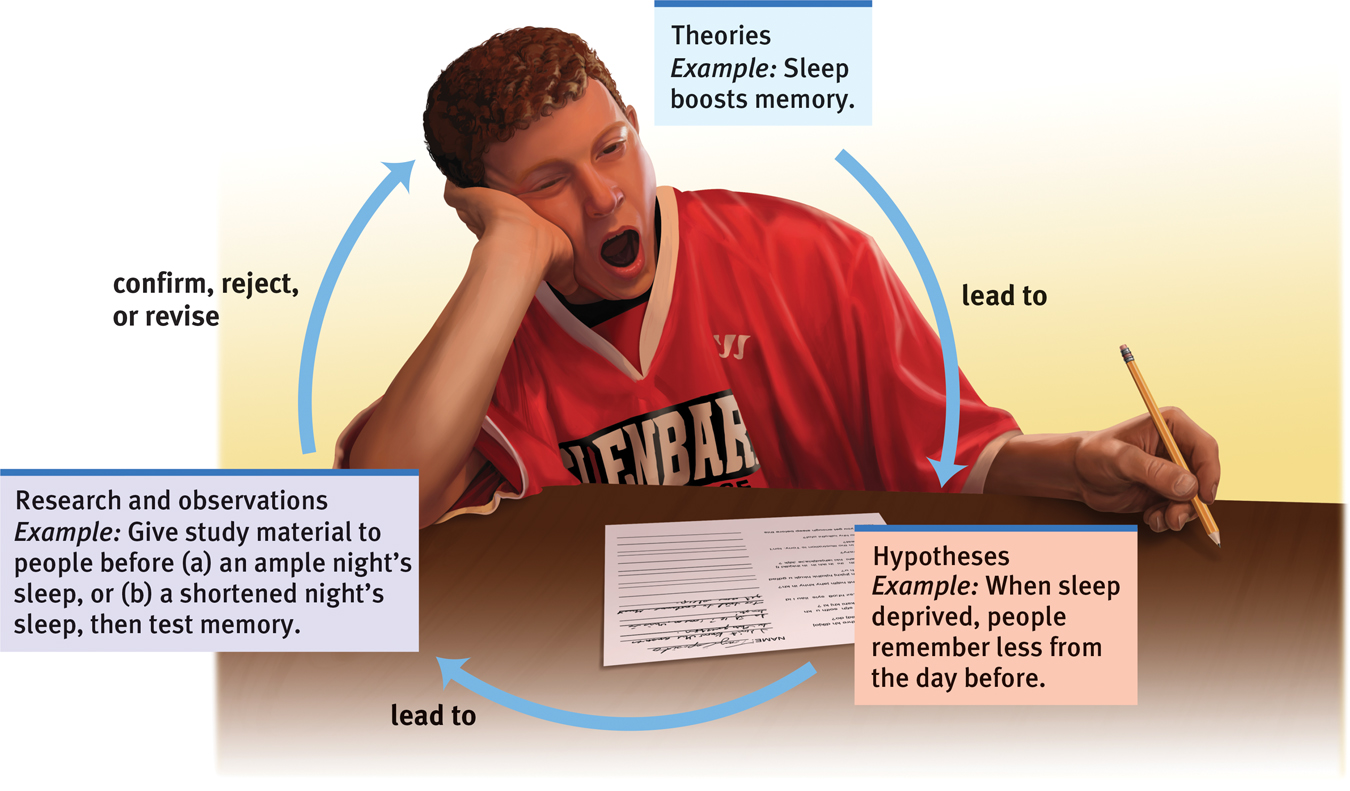

A theory about the effects of sleep on memory, for example, helps us organize countless sleep-

Yet no matter how reasonable a theory may sound—

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1The scientific method A self-

Our theories can bias our observations. Having theorized that better memory springs from more sleep, we may see what we expect: We may perceive sleepy people’s comments as less insightful. The urge to see what we expect is ever-

To avoid biases, psychologists report their research with precise operational definitions of procedures and concepts. Sleep deprived, for example, may be defined as “X hours less” than the person’s natural sleep. Using these carefully worded statements, others can replicate (repeat) the original observations with different participants, materials, and circumstances. The first study of hindsight bias (the tendency to believe, after learning an outcome, that one would have foreseen it) aroused psychologists’ curiosity. Now, after many successful replications with differing people and questions, we feel sure of the phenomenon’s power. Although a “mere replication” of someone else’s research seldom makes headline news, recent instances of fraudulent or hard-

In the end, our theory will be useful if it (1) organizes a range of self-

As we will see next, we can test our hypotheses and refine our theories using descriptive methods (which describe behaviors, often through case studies, surveys, or naturalistic observations), correlational methods (which associate different factors), and experimental methods (which manipulate factors to discover their effects). To think critically about popular psychology claims, we need to understand these methods and know what conclusions they allow.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What does a good theory do?

1. It organizes observed facts. 2. It implies hypotheses that offer testable predictions and, sometimes, practical applications. 3. It often stimulates further research.

- Why is replication important?

Psychologists watch eagerly for new findings, but they also proceed with caution—