3.2 Description

3-

The starting point of any science is description. In everyday life, we all observe and describe people, often drawing conclusions about why they act as they do. Professional psychologists do much the same, though more objectively and systematically, through

28

- case studies (in-depth analyses of individuals or groups).

- naturalistic observations (watching and recording the natural behavior of many individuals).

- surveys and interviews (asking people questions).

The Case Study

“‘Well my dear,’ said Miss Marple, ‘human nature is very much the same everywhere, and of course, one has opportunities of observing it at closer quarters in a village’.”

Agatha Christie, The Tuesday Club Murders, 1933

Among the oldest research methods, the case study examines one individual or group in depth in the hope of revealing things true of us all. Some examples: Much of our early knowledge about the brain came from case studies of individuals who suffered a particular impairment after damage to a certain brain region. Jean Piaget taught us about children’s thinking after carefully observing and questioning only a few children. Studies of only a few chimpanzees have revealed their capacity for understanding and language. Intensive case studies are sometimes very revealing. They show us what can happen, and they often suggest directions for further study.

But atypical individual cases may mislead us. Unrepresentative information can lead to mistaken judgments and false conclusions. Indeed, anytime a researcher mentions a finding (Smokers die younger: 95 percent of men over 85 are nonsmokers) someone is sure to offer a contradictory anecdote (Well, I have an uncle who smoked two packs a day and lived to be 89). Dramatic stories and personal experiences (even psychological case examples) command our attention and are easily remembered. Journalists understand that, and often begin their articles with personal stories. Stories move us. But stories can mislead. Which of the following do you find more memorable? (1) “In one study of 1300 dream reports concerning a kidnapped child, only 5 percent correctly envisioned the child as dead” (Murray & Wheeler, 1937). (2) “I know a man who dreamed his sister was in a car accident, and two days later she died in a head-

The point to remember: Individual cases can suggest fruitful ideas. What’s true of all of us can be glimpsed in any one of us. But to discern the general truths that cover individual cases, we must answer questions with other research methods.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- We cannot assume that case studies always reveal general principles that apply to all of us. Why not?

Case studies involve only one individual or group, so we can’t know for sure whether the principles observed would apply to a larger population.

Naturalistic Observation

A second descriptive method records behavior in natural environments. These naturalistic observations range from watching chimpanzee societies in the jungle, to videotaping and analyzing parent-

Naturalistic observation has mostly been “small science”—science that can be done with pen and paper rather than fancy equipment and a big budget (Provine, 2012). But new technologies are enabling “big data” observations. New smart-

29

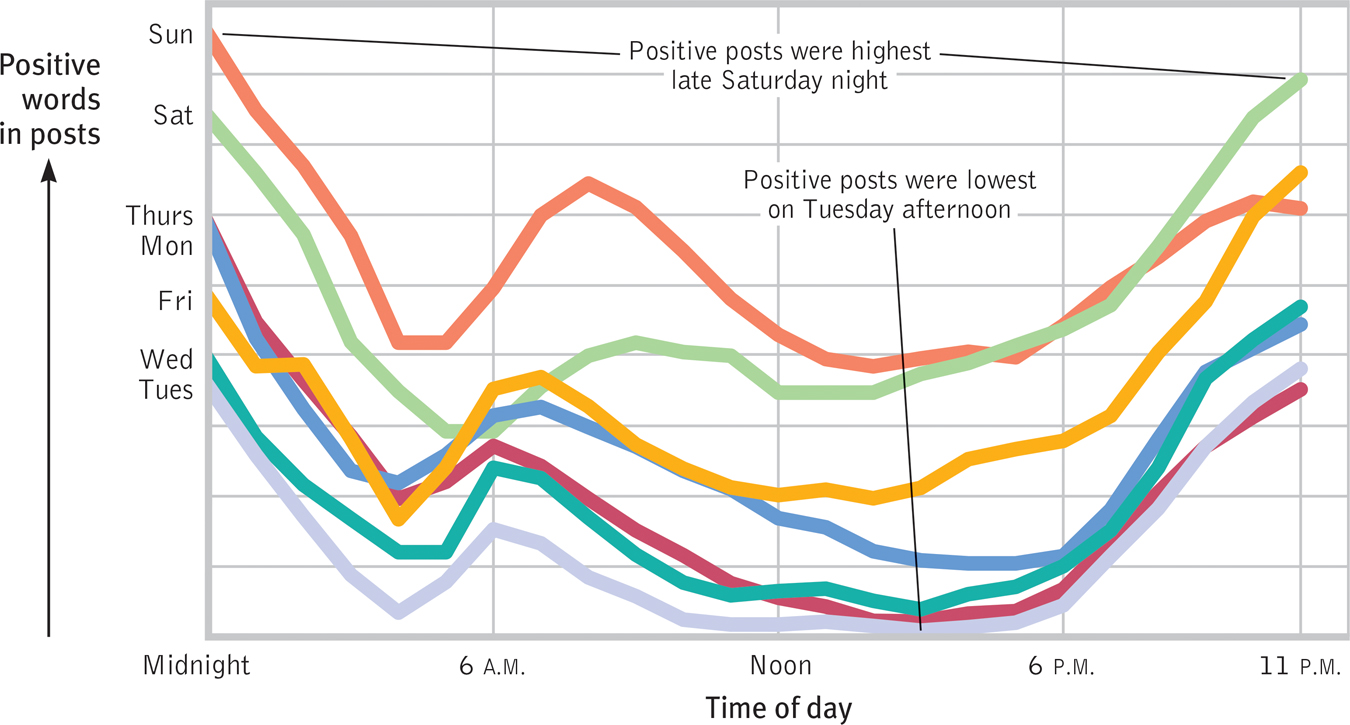

Another research team studied the ups and downs of human moods by counting positive and negative words in 504 million Twitter messages from 84 countries (Golder & Macy, 2011). As FIGURE 3.2 shows, people seem happier on weekends, shortly after arising, and in the evenings. (Are late Saturday evenings often a happy time for you, too?)

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2Twitter message moods, by time and by day This illustrates how, without knowing anyone’s identity, big data enable researchers to study human behavior on a massive scale. It now is also possible to associate people’s moods with, for example, their locations or with the weather, and to study the spread of ideas through social networks. (Data from Golder & Macy, 2011.)

Like the case study, naturalistic observation does not explain behavior. It describes it. Nevertheless, descriptions can be revealing. We once thought, for example, that only humans use tools. Then naturalistic observation revealed that chimpanzees sometimes insert a stick in a termite mound and withdraw it, eating the stick’s load of termites. Such unobtrusive naturalistic observations paved the way for later studies of animal thinking, language, and emotion, which further expanded our understanding of our fellow animals. “Observations, made in the natural habitat, helped to show that the societies and behavior of animals are far more complex than previously supposed,” chimpanzee observer Jane Goodall noted (1998). Thanks to researchers’ observations, we know that chimpanzees and baboons use deception: Psychologists repeatedly saw one young baboon pretending to have been attacked by another as a tactic to get its mother to drive the other baboon away from its food (Whiten & Byrne, 1988).

Naturalistic observations also illuminate human behavior. Here are four findings you might enjoy:

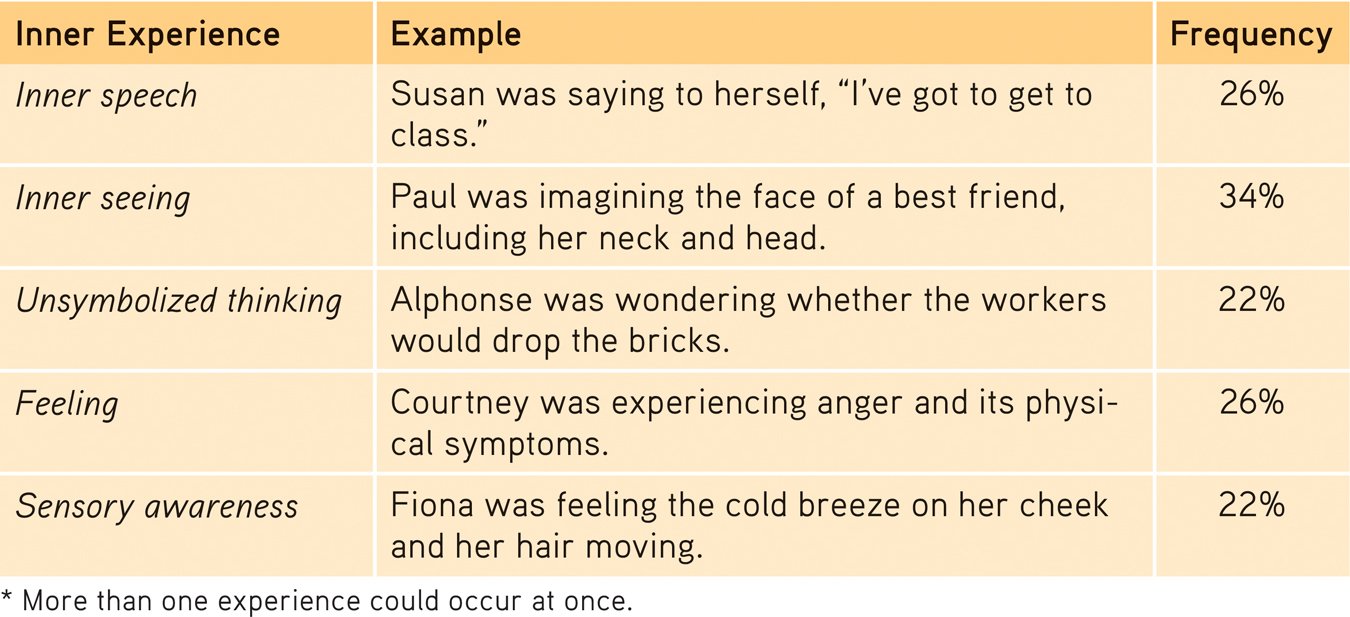

Table 3.1

Table 3.1A Penny for Your Thoughts: The Inner Experience of University Students)

- A funny finding. We humans laugh 30 times more often in social situations than in solitary situations. (Have you noticed how seldom you laugh when alone?) As we laugh, 17 muscles contort our mouth and squeeze our eyes, and we emit a series of 75-millisecond vowel-like sounds, spaced about one-fifth of a second apart (Provine, 2001).

- Sounding out students. What, really, are introductory psychology students saying and doing during their everyday lives? To find out, Matthias Mehl and James Pennebaker (2003) equipped 52 such students from the University of Texas with electronic recorders. For up to four days, the recorders captured 30 seconds of the students’ waking hours every 12.5 minutes, thus enabling the researchers to eavesdrop on more than 10,000 half-minute life slices by the end of the study. On what percentage of the slices do you suppose they found the students talking with someone? What percentage captured the students at a computer? The answers: 28 and 9 percent. (What percentage of your waking hours are spent in these activities?)

- What’s on your mind? To find out what was on the minds of their University of Nevada, Las Vegas, students, Christopher Heavey and Russell Hurlburt (2008) gave them beepers. On a half-dozen occasions, a beep interrupted students’ daily activities, signaling them to pull out a notebook and record their inner experience at that moment. When the researchers later coded the reports in categories, they found five common forms of inner experience (TABLE 3.1).

- Culture, climate, and the pace of life. Naturalistic observation also enabled Robert Levine and Ara Norenzayan (1999) to compare the pace of life in 31 countries. (Their operational definition of pace of life included walking speed, the speed with which postal clerks completed a simple request, and the accuracy of public clocks.) Their conclusion: Life is fastest paced in Japan and Western Europe, and slower paced in economically less-developed countries. People in colder climates also tend to live at a faster pace (and are more prone to die from heart disease).

30

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of naturalistic observation, such as Mehl and Pennebaker used in this study?

The researchers were able to carefully observe and record naturally occurring behaviors outside the artificiality of the lab. However, outside the lab they were not able to control for all the factors that may have influenced the everyday interactions they were recording.

Naturalistic observation offers interesting snapshots of everyday life, but it does so without controlling for all the factors that may influence behavior. It’s one thing to observe the pace of life in various places, but another to understand what makes some people walk faster than others.

The Survey

A survey looks at many cases in less depth. A survey asks people to report their behavior or opinions. Questions about everything from sexual practices to political opinions are put to the public. In recent surveys:

- Saturdays and Sundays have been the week’s happiest days (confirming what the Twitter researchers found) (Stone et al., 2012).

- 1 in 5 people across 22 countries report believing that alien beings have come to Earth and now walk among us disguised as humans (Ipsos, 2010b).

- 68 percent of all humans—some 4.6 billion people—say that religion is important in their daily lives (from Gallup World Poll data analyzed by Diener et al., 2011).

But asking questions is tricky, and the answers often depend on how questions are worded and respondents are chosen.

31

Wording EffectsEven subtle changes in the order or wording of questions can have major effects. People are much more approving of “aid to the needy” than of “welfare,” of “affirmative action” than of “preferential treatment,” of “not allowing” televised cigarette ads and pornography than of “censoring” them, and of “revenue enhancers” than of “taxes.” In another survey, adults estimated a 55 percent chance “that I will live to be 85 years old or older,” while comparable other adults estimated a 68 percent chance “that I will die at 85 years old or younger” (Payne et al., 2013). Because wording is such a delicate matter, critical thinkers will reflect on how the phrasing of a question might affect people’s expressed opinions.

Random SamplingIn everyday thinking, we tend to generalize from samples we observe, especially vivid cases. Given (a) a statistical summary of a professor’s student evaluations and (b) the vivid comments of a biased sample (two irate students), an administrator’s impression of the professor may be influenced as much by the two unhappy students as by the many favorable evaluations in the statistical summary. The temptation to ignore the sampling bias and to generalize from a few vivid but unrepresentative cases is nearly irresistible.

With very large samples, estimates become quite reliable. E is estimated to represent 12.7 percent of the letters in written English. E, in fact, is 12.3 percent of the 925,141 letters in Melville’s Moby-Dick, 12.4 percent of the 586,747 letters in Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, and 12.1 percent of the 3,901,021 letters in 12 of Mark Twain’s works (Chance News, 1997).

So how do you obtain a representative sample of, say, the students at your college or university? It’s not always possible to survey the whole group you want to study and describe. How could you choose a group that would represent the total student population? Typically, you would seek a random sample, in which every person in the entire group has an equal chance of participating. You might number the names in the general student listing and then use a random number generator to pick your survey participants. (Sending each student a questionnaire wouldn’t work because the conscientious people who returned it would not be a random sample.) Large representative samples are better than small ones, but a small representative sample of 100 is better than an unrepresentative sample of 500.

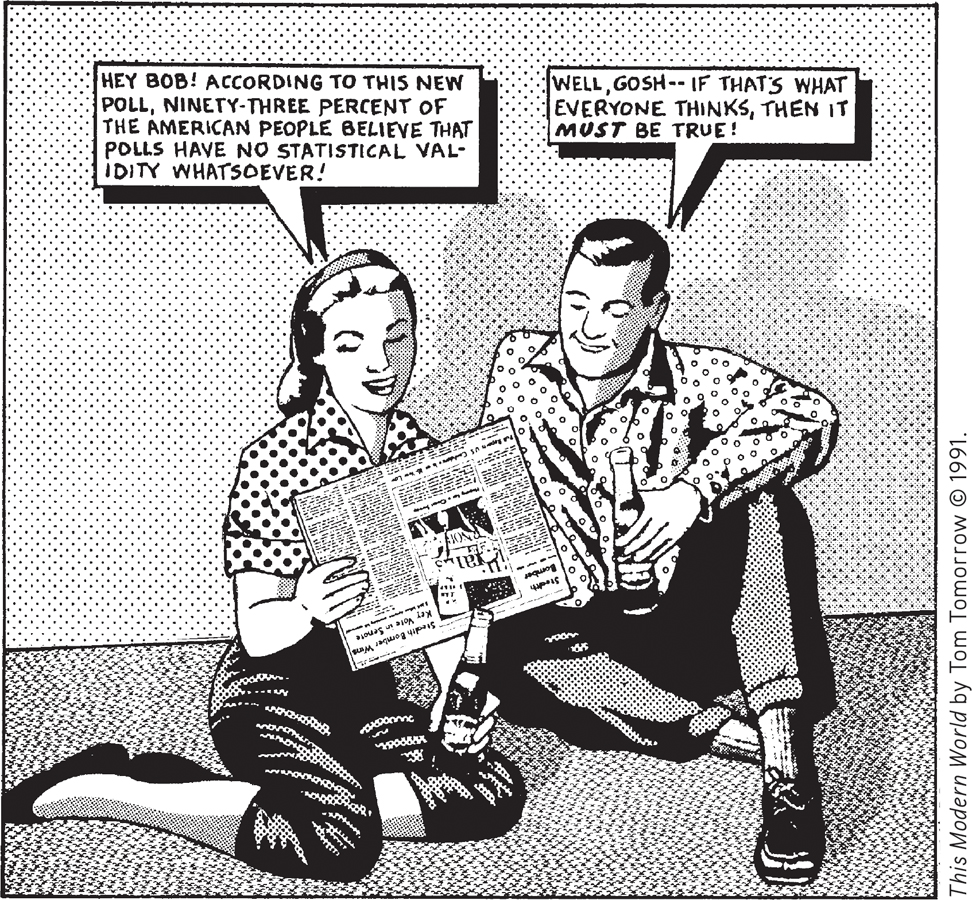

Political pollsters sample voters in national election surveys just this way. Using some 1500 randomly sampled people, drawn from all areas of a country, they can provide a remarkably accurate snapshot of the nation’s opinions. Without random sampling, large samples—

The point to remember: Before accepting survey findings, think critically. Consider the sample. The best basis for generalizing is from a representative sample. You cannot compensate for an unrepresentative sample by simply adding more people.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is an unrepresentative sample, and how do researchers avoid it?

An unrepresentative sample is a survey group that does not represent the population being studied. Random sampling helps researchers form a representative sample, because each member of the population has an equal chance of being included.