3.4 Experimentation

3-

Happy are they, remarked the Roman poet Virgil, “who have been able to perceive the causes of things.” How might psychologists perceive causes in correlational studies, such as the correlation between breast feeding and intelligence?

Researchers have found that the intelligence scores of children who were breast-

What do such findings mean? Do smarter mothers have smarter children? (Breast-

Recall that in a well-done survey, random sampling is important. In an experiment, random assignment is equally important.

To experiment with breast feeding, one research team randomly assigned some 17,000 Belarus newborns and their mothers either to a control group given normal pediatric care, or an experimental group that promoted breast feeding, thus increasing expectant mothers’ breast intentions (Kramer et al., 2008). At three months of age, 43 percent of the infants in the experimental group were being exclusively breast-

With parental permission, one British research team directly experimented with breast milk. They randomly assigned 424 hospitalized premature infants either to formula feedings or to breast-

No single experiment is conclusive, of course. But randomly assigning participants to one feeding group or the other effectively eliminated all factors except nutrition. This supported the conclusion that for developing intelligence, breast is indeed best. If test performance changes when we vary infant nutrition, then we infer that nutrition matters.

The point to remember: Unlike correlational studies, which uncover naturally occurring relationships, an experiment manipulates a factor to determine its effect.

Consider, then, how we might assess therapeutic interventions. Our tendency to seek new remedies when we are ill or emotionally down can produce misleading testimonies. If three days into a cold we start taking vitamin C tablets and find our cold symptoms lessening, we may credit the pills rather than the cold naturally subsiding. In the 1700s, bloodletting seemed effective. People sometimes improved after the treatment; when they didn’t, the practitioner inferred the disease was too advanced to be reversed. So, whether or not a remedy is truly effective, enthusiastic users will probably endorse it. To determine its effect, we must control for other factors.

And that is precisely how investigators evaluate new drug treatments and new methods of psychological therapy. They randomly assign participants in these studies to research groups. One group receives a treatment (such as a medication). The other group receives a pseudotreatment—

In double-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What measures do researchers use to prevent the placebo effect from confusing their results?

Research designed to prevent the placebo effect randomly assigns participants to an experimental group (which receives the real treatment) or to a control group (which receives a placebo). A comparison of the results will demonstrate whether the real treatment produces better results than belief in that treatment.

Independent and Dependent Variables

Here is an even more potent example: The drug Viagra was approved for use after 21 clinical experiments. One trial was an experiment in which researchers randomly assigned 329 men with erectile disorder to either an experimental group (Viagra takers) or a control group (placebo takers given an identical-

This simple experiment manipulated just one factor: the drug dosage (none versus peak dose). We call this experimental factor the independent variable because we can vary it independently of other factors, such as the men’s age, weight, and personality. Other factors, which can potentially influence the results of the experiment, are called confounding variables. Random assignment controls for possible confounding variables.

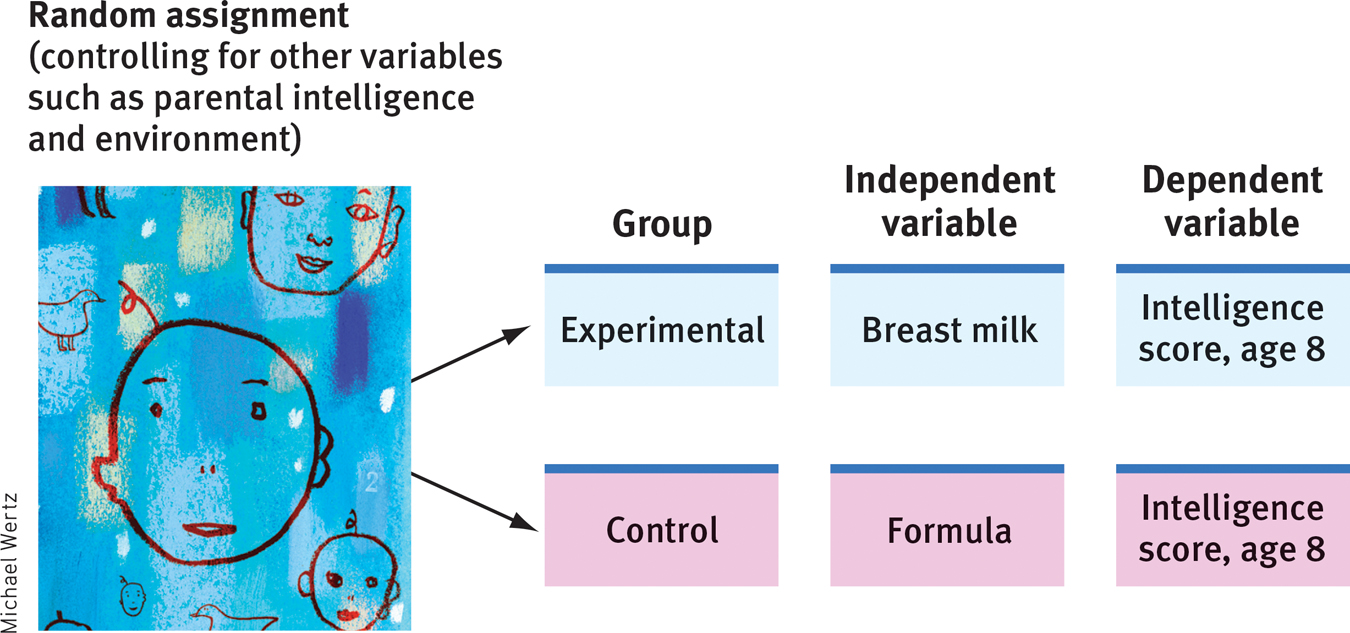

Experiments examine the effect of one or more independent variables on some measurable behavior, called the dependent variable because it can vary depending on what takes place during the experiment. Both variables are given precise operational definitions, which specify the procedures that manipulate the independent variable (the precise drug dosage and timing in this study) or measure the dependent variable (the questions that assessed the men’s responses). These definitions provide a level of precision that enables others to repeat the study. (See FIGURE 3.6 for the British breast milk experiment’s design.)

Figure 3.6

Figure 3.6Experimentation To discern causation, psychologists may randomly assign some participants to an experimental group, others to a control group. Measuring the dependent variable (intelligence score in later childhood) will determine the effect of the independent variable (type of milk).

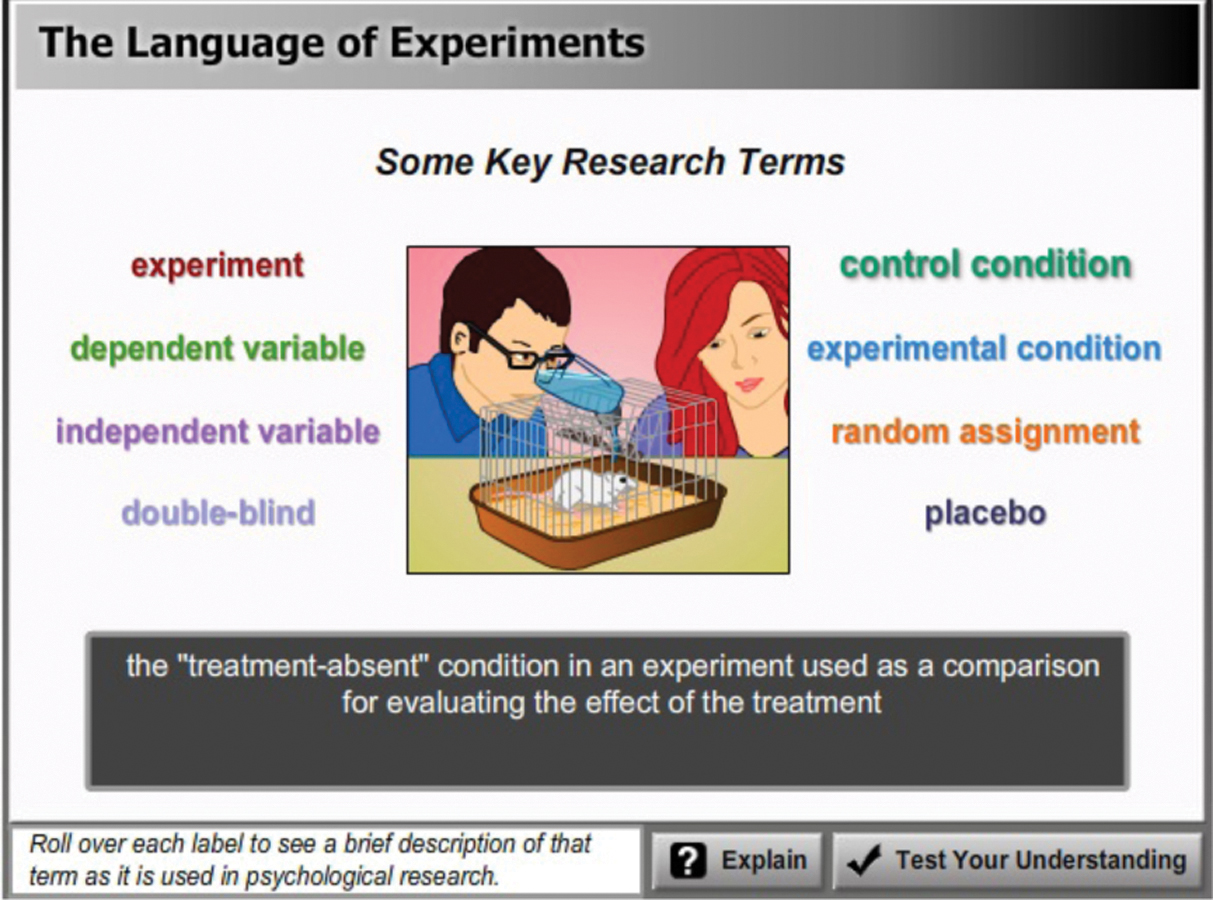

To review and test your understanding of experimental methods and concepts, visit Launch Pad’s Concept Practice: The Language of Experiments, and the interactive PsychSim 6: Understanding Psychological Research.

To review and test your understanding of experimental methods and concepts, visit Launch Pad’s Concept Practice: The Language of Experiments, and the interactive PsychSim 6: Understanding Psychological Research.

Let’s pause to check your understanding using a simple psychology experiment: To test the effect of perceived ethnicity on the availability of a rental house, Adrian Car-

Experiments can also help us evaluate social programs. Do early childhood education programs boost impoverished children’s chances for success? What are the effects of different antismoking campaigns? Do school sex-

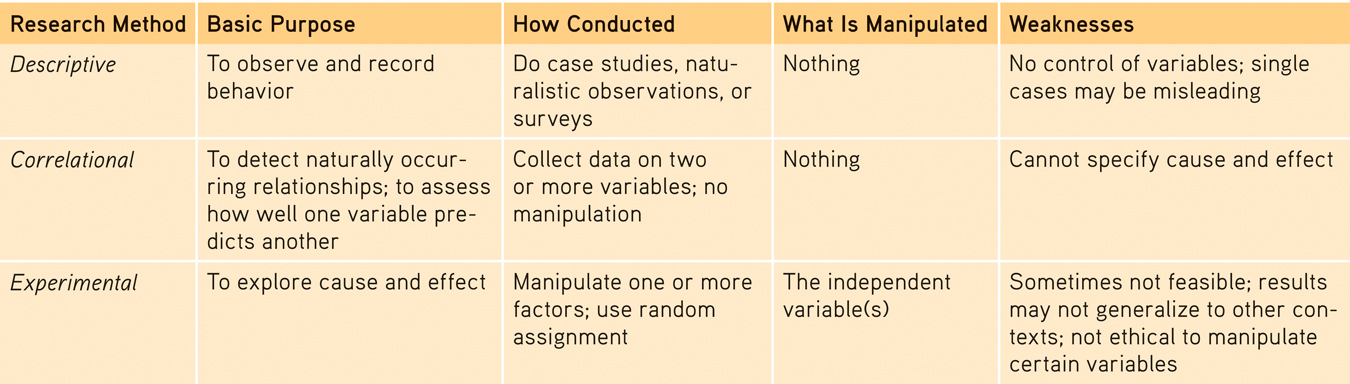

Let’s recap. A variable is anything that can vary (infant nutrition, intelligence, TV exposure—

Table 3.3

Table 3.3Comparing Research Methods

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- In the rental housing experiment, what was the independent variable? The dependent variable?

The independent variable, which the researchers manipulated, was the set of ethnically distinct names. The dependent variable, which they measured, was the positive response rate.

- By using random assignment, researchers are able to control for ______________ ___________ , which are other factors besides the independent variable (s) that may influence research results.

confounding variables

- Match the term on the left with the description on the right.

| 1. double- |

a. helps researchers generalize from a small set of survey responses to a larger population |

| 2. random sampling | b. helps minimize preexisting differences between experimental and control groups |

| 3. random assignment | c. controls for the placebo effect; neither researchers nor participants know who receives the real treatment |

1. c, 2. a, 3. b

- Why, when testing a new drug to control blood pressure, would we learn more about its effectiveness from giving it to half of the participants in a group of 1000 than to all 1000 participants?

We learn more about the drug’s effectiveness when we can compare the results of those who took the drug (the experimental group) with the results of those who did not (the control group). If we gave the drug to all 1000 participants, we would have no way of knowing whether the drug is serving as a placebo or is actually medically effective.

Predicting Real Behavior

3-

When you see or hear about psychological research, do you ever wonder whether people’s behavior in the lab will predict their behavior in real life? Does detecting the blink of a faint red light in a dark room say anything useful about flying a plane at night? After viewing a violent, sexually explicit film, does an aroused man’s increased willingness to push buttons that he thinks will electrically shock a woman really say anything about whether violent pornography makes a man more likely to abuse a woman?

Before you answer, consider: The experimenter intends the laboratory environment to be a simplified reality—

An experiment’s purpose is not to re-

When psychologists apply laboratory research on aggression to actual violence, they are applying theoretical principles of aggressive behavior, principles they have refined through many experiments. Similarly, it is the principles of the visual system, developed from experiments in artificial settings (such as looking at red lights in the dark), that researchers apply to more complex behaviors such as night flying. And many investigations show that principles derived in the laboratory do typically generalize to the everyday world (Anderson et al., 1999).

The point to remember: Psychological science focuses less on particular behaviors than on seeking general principles that help explain many behaviors.