41.1 Coping With Stress

41-

Stressors are unavoidable. This fact, coupled with the fact that persistent stress correlates with heart disease, depression, and lowered immunity, gives us a clear message. We need to learn to cope with the stress in our lives, alleviating it with emotional, cognitive, or behavioral methods. We address some stressors directly, with problem-focused coping. If our impatience leads to a family fight, we may go directly to that family member to work things out. We tend to use problem-

When challenged, some of us tend to respond with cool problem-

Personal Control

41-

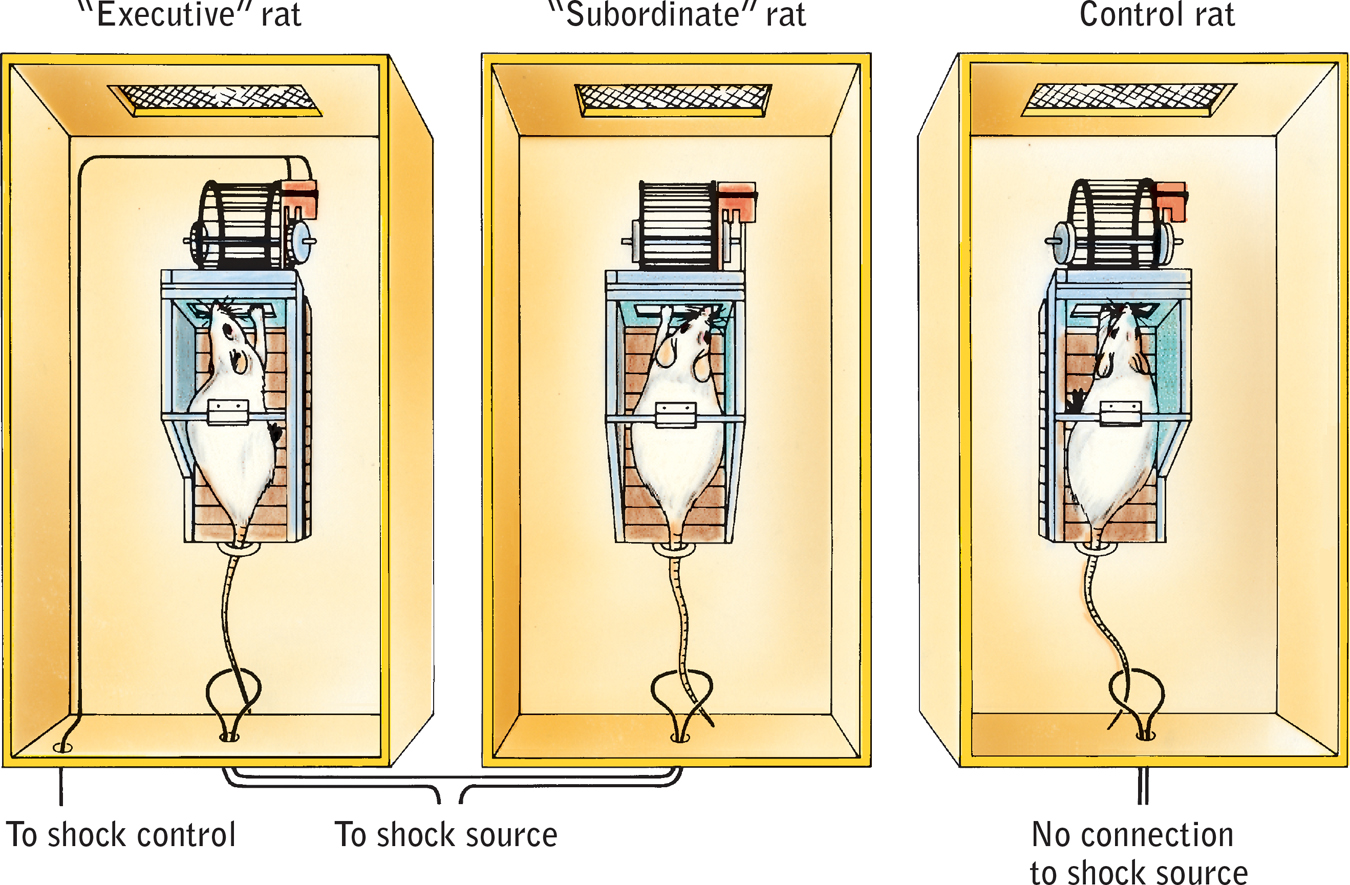

Picture the scene: Two rats receive simultaneous shocks. One can turn a wheel to stop the shocks (as illustrated in FIGURE 41.1). The helpless rat, but not the wheel turner, becomes more susceptible to ulcers and lowered immunity to disease (Laudenslager & Reite, 1984). In humans, too, uncontrollable threats trigger the strongest stress responses (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004).

Figure 41.1

Figure 41.1Health consequences of a loss of control The “executive” rat at the left can switch off the tail shock by turning the wheel. Because it has control over the shock, it is no more likely to develop ulcers than is the unshocked control rat on the right. The “subordinate” rat in the center receives the same shocks as the executive rat, but with no control over the shocks. It is, therefore, more likely to develop ulcers. (Adapted from Weiss, 1977.)

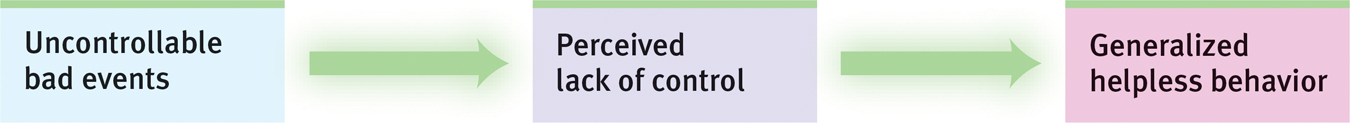

At times, we all feel helpless, hopeless, and depressed after experiencing a series of bad events beyond our control. Martin Seligman and his colleagues have shown that for some animals and people, a series of uncontrollable events creates a state of learned helplessness, with feelings of passive resignation (FIGURE 41.2). In one series of experiments, dogs were strapped in a harness and given repeated shocks, with no opportunity to avoid them (Seligman & Maier, 1967). Later, when placed in another situation where they could escape the punishment by simply leaping a hurdle, the dogs cowered as if without hope. Other dogs that had been able to escape the first shocks reacted differently. They had learned they were in control and easily escaped the shocks in the new situation (Seligman & Maier, 1967). In other experiments, people have shown similar patterns of learned helplessness (Abramson et al., 1978, 1989; Seligman, 1975).

Figure 41.2

Figure 41.2Learned helplessness When animals and people experience no control over repeated bad events, they often learn helplessness.

Perceiving a loss of control, we become more vulnerable to ill health. A famous study of elderly nursing home residents with little perceived control over their activities found that they declined faster and died sooner than those given more control (Rodin, 1986). Workers able to adjust office furnishings and control interruptions and distractions in their work environment have also experienced less stress (O’Neill, 1993). Such findings help explain why British civil service workers at the executive grades have tended to outlive those at clerical or laboring grades, and why Finnish workers with low job stress have been less than half as likely to die of strokes or heart disease as were those with a demanding job and little control. The more control workers have, the longer they live (Bosma et al., 1997, 1998; Kivimaki et al., 2002; Marmot et al., 1997).

Control also helps explain a link between economic status and longevity (Jokela et al., 2009). In one study of 843 grave markers in an old graveyard in Glasgow, Scotland, those with the costliest, highest pillars (indicating the most affluence) tended to have lived the longest (Carroll et al., 1994). Likewise, those living in Scottish regions with the least overcrowding and unemployment have the greatest longevity. There and elsewhere, high economic status predicts a lower risk of heart and respiratory diseases (Sapolsky, 2005). Wealth predicts better health among children, too (Chen, 2004). With higher economic status come reduced risks of low birth weight, infant mortality, smoking, and violence. Even among other primates, those at the bottom of the social pecking order have been more likely than their higher-

Why does perceived loss of control predict health problems? Because losing control provokes an outpouring of stress hormones. When rats cannot control shock or when primates or humans feel unable to control their environment, stress hormone levels rise, blood pressure increases, and immune responses drop (Rodin, 1986; Sapolsky, 2005). One study found these effects among nurses, who reported their workload and their level of personal control on the job. The greater their workload, the higher their cortisol level and blood pressure—

Increasing control—

In the case of nursing home patients, 93 percent of those who were encouraged to exert more control became more alert, active, and happy (Rodin, 1986). As researcher Ellen Langer concluded, “Perceived control is basic to human functioning” (1983, p. 291). “For the young and old alike,” she suggested, environments should enhance people’s sense of control over their world. No wonder mobile devices and DVRs, which enhance our control of the content and timing of our entertainment, are so popular.

Google incorporates these principles effectively. Each week, Google employees can spend 20 percent of their working time on projects they find personally interesting. This Innovation Time Off program increases employees’ personal control over their work environment, and it has paid off. Gmail was developed this way.

People thrive when they live in conditions of personal freedom and empowerment. At the national level, citizens of stable democracies report higher levels of happiness (Inglehart et al., 2008).

So, some freedom and control are better than none. But does ever-

Internal Versus External Locus of ControlIf experiencing a loss of control can be stressful and unhealthy, do people who generally feel in control of their lives enjoy better health? Consider your own feelings of control. Do you believe that your life is beyond your control? That the world is run by a few powerful people? That getting a good job depends mainly on being in the right place at the right time? Or do you more strongly believe that you control your own fate? That each of us can influence our government’s decisions? That being a success is a matter of hard work?

Hundreds of studies have compared people who differ in their perceptions of control. On the one side are those who have what Julian Rotter called an external locus of control, the perception that chance or outside forces control their fate. On the other side are those who perceive an internal locus of control, who believe they control their own destiny. In study after study, the “internals” have achieved more in school and work, acted more independently, enjoyed better health, and felt less depressed than did the “externals” (Lefcourt, 1982; Ng et al., 2006). In one long-

Another way to say that we believe we are in control of our own life is to say we have free will, or that we can control our own willpower. Studies show that people who believe in their freedom learn better, perform better at work, behave more helpfully, and have a stronger desire to punish rule breakers (Clark et al., 2014; Job et al., 2010; Stillman et al., 2010).

Compared with their parents’ generation, more young Americans now endorse an external locus of control (Twenge et al., 2004). This shift may help explain an associated increase in rates of depression and other psychological disorders in young people (Twenge et al., 2010).

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- To cope with stress, we tend to use ____________ -focused (emotion/problem) strategies when we feel in control of our world, and _____________ -focused (emotion/problem) strategies when we believe we cannot change a situation.

problem; emotion

Depleting and Strengthening Self-

41-

Self-control is the ability to control impulses and delay short-

Self-

Exercising willpower decreases neural activation in regions associated with mental control (Wagner et al., 2013). Might sugar provide a sweet solution to self-

Researchers do not encourage candy bar diets to improve self-

Decreased mental energy after exercising self-

The point to remember: Develop self-

Explanatory Style: Optimism Versus Pessimism

41-

In The How of Happiness, psychologist Sonja Lyubomirsky (2008) tells the true story of Randy. By any measure, Randy lived a hard life. His dad and best friend died by suicide. Growing up, his mother’s boyfriend treated him poorly. Randy’s own first marriage was troubled. His wife was unfaithful, and they divorced. Despite these setbacks, Randy is a happy person whose presence can light up a room. He remarried and enjoys his role as stepfather to three boys. He also finds his work life to be rewarding. Randy says he survived his life challenges by seeing the “silver lining in the cloud.”

Randy’s story illustrates how our outlook—

Optimistic students have also tended to get better grades because they often respond to setbacks with the hopeful attitude that effort, good study habits, and self-

Consider the consistency and startling magnitude of the optimism and positive emotions factor in several other studies:

- One research team followed 941 Dutch people, ages 65 to 85, for nearly a decade (Giltay et al., 2004, 2007). Among those in the lowest optimism quartile, 57 percent died, as did only 30 percent of the top optimism quartile.

- When Finnish researchers followed 2428 men for up to a decade, the number of deaths among those with a bleak, hopeless outlook was more than double that found among their optimistic counterparts (Everson et al., 1996). American researchers found the same when following 4256 Vietnam-era veterans (Phillips et al., 2009).

- A now-famous study followed up on 180 Catholic nuns who had written brief autobiographies at about 22 years of age and had thereafter lived similar lifestyles. Those who had expressed happiness, love, and other positive feelings in their autobiographies lived an average 7 years longer than their more dour counterparts (Danner et al., 2001). By age 80, some 54 percent of those expressing few positive emotions had died, as had only 24 percent of the most positive spirited.

Optimism runs in families, so some people truly are born with a sunny, hopeful outlook. With identical twins, if one is optimistic, the other often will be as well (Mosing et al., 2009). One genetic marker of optimism is a gene that enhances the social-

“The optimist proclaims we live in the best of all possible worlds, and the pessimist fears this is true.”

James Branch Cabell, The Silver Stallion, 1926

The good news is that all of us, even the most pessimistic, can learn to become more optimistic. Compared with pessimists who simply kept diaries of their daily activities, those who became skilled at seeing the bright side of difficult situations and viewing their goals as achievable reported lower levels of depression (Sergeant & Mongrain, 2014). Optimism is the light bulb that can brighten anyone’s mood.

Social Support

41-

Social support—

People need people. Some fill this need by connecting with friends, family, coworkers, members of a faith community, or other support groups. The need to belong is so strong that people will sometimes risk their health to gain social acceptance (Rawn & Vohs, 2011). Others connect in positive, happy, supportive marriages. In one analysis of more than 72,000 individuals, people in low-

What explains the link between social support and health? Are middle-

Social support calms us and reduces blood pressure and stress hormones. Numerous studies support this finding (Hostinar et al., 2014; Uchino et al., 1996, 1999). To see if social support might calm people’s response to threats, one research team subjected happily married women, while lying in an fMRI machine, to the threat of electric shock to an ankle (Coan et al., 2006). During the experiment, some women held their husband’s hand. Others held the hand of an unknown person or no hand at all. While awaiting the occasional shocks, women holding their husband’s hand showed less activity in threat-

Social support fosters stronger immune functioning. Volunteers in studies of resistance to cold viruses showed this effect (Cohen et al., 1997, 2004). Healthy volunteers inhaled nasal drops laden with a cold virus and were quarantined and observed for five days. (In these experiments, more than 600 volunteers received $800 each to endure this experience.) Age, race, sex, smoking, and other health habits being equal, those with the most social ties were least likely to catch a cold. If they did catch one, they produced less mucus. More sociability meant less susceptibility. The cold fact is that the effect of social ties is nothing to sneeze at!

Close relationships give us an opportunity for “open heart therapy,” a chance to confide painful feelings (Frattaroli, 2006). Talking about a stressful event can temporarily arouse us, but in the long run it calms us, by calming limbic system activity (Lieber-

“Woe to one who is alone and falls and does not have another to help.”

Ecclesiastes 4:10

Suppressing emotions can be detrimental to physical health. When health psychologist James Pennebaker (1985) surveyed more than 700 undergraduate women, about 1 in 12 of them reported a traumatic sexual experience in childhood. The sexually abused women—

Even writing about personal traumas in a diary can help (Burton & King, 2008; Hemenover, 2003; Lyubomirsky et al., 2006). In an analysis of 633 trauma victims, writing therapy was as effective as psychotherapy in reducing psychological trauma (van Emmerik et al., 2013). In another experiment, volunteers who wrote trauma diaries had fewer health problems during the ensuing four to six months (Pennebaker, 1990). As one participant explained, “Although I have not talked with anyone about what I wrote, I was finally able to deal with it, work through the pain instead of trying to block it out. Now it doesn’t hurt to think about it.”

If we are aiming to exercise more, drink less, quit smoking, or be a healthy weight, our social ties can tug us away from or toward our goal. If you are trying to achieve some goal, think about whether your social network can help or hinder you. That social net covers not only the people you know but friends of your friends, and friends of their friends. That’s three degrees of separation between you and the most remote people. Within that network, others can influence your thoughts, feelings, and actions without your awareness (Christakis & Fowler, 2009). Obesity, for example, spreads within networks in ways that seem not merely to reflect people’s seeking out similar others.