43.1 Conformity: Complying With Social Pressures

43-

Please continue to the next section.

Automatic Mimicry

Fish swim in schools. Birds fly in flocks. And humans, too, tend to go with their group, to think what it thinks and do what it does. Behavior is contagious. Chimpanzees are more likely to yawn after observing another chimpanzee yawn (Anderson et al., 2004). Ditto for humans. If one of us yawns, laughs, coughs, stares at the sky, or checks a cell phone, others in our group will often do the same. Yawn mimicry can also occur across species: Dogs more often yawn after observing their owners’ yawn (Silva et al., 2012). Even just reading about yawning increases people’s yawning (Provine, 2012), as perhaps you have noticed?

Like the chameleon lizards that take on the color of their surroundings, we humans take on the emotional tones of those around us. Just hearing someone reading a neutral text in either a happy-

Tanya Chartrand and John Bargh captured this mimicry, which they call the chameleon effect (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999). They had students work in a room alongside another person, who was actually a confederate working for the experimenters. Sometimes the confederates rubbed their own face. Sometimes they shook their foot. Sure enough, the students tended to rub their face when with the face-

We should not be surprised, then, that intricate studies show that obesity, sleep loss, drug use, loneliness, and happiness spread through social networks (Christakis & Fowler, 2009). We and our friends form a social system. On websites, positive ratings generate more positive ratings—

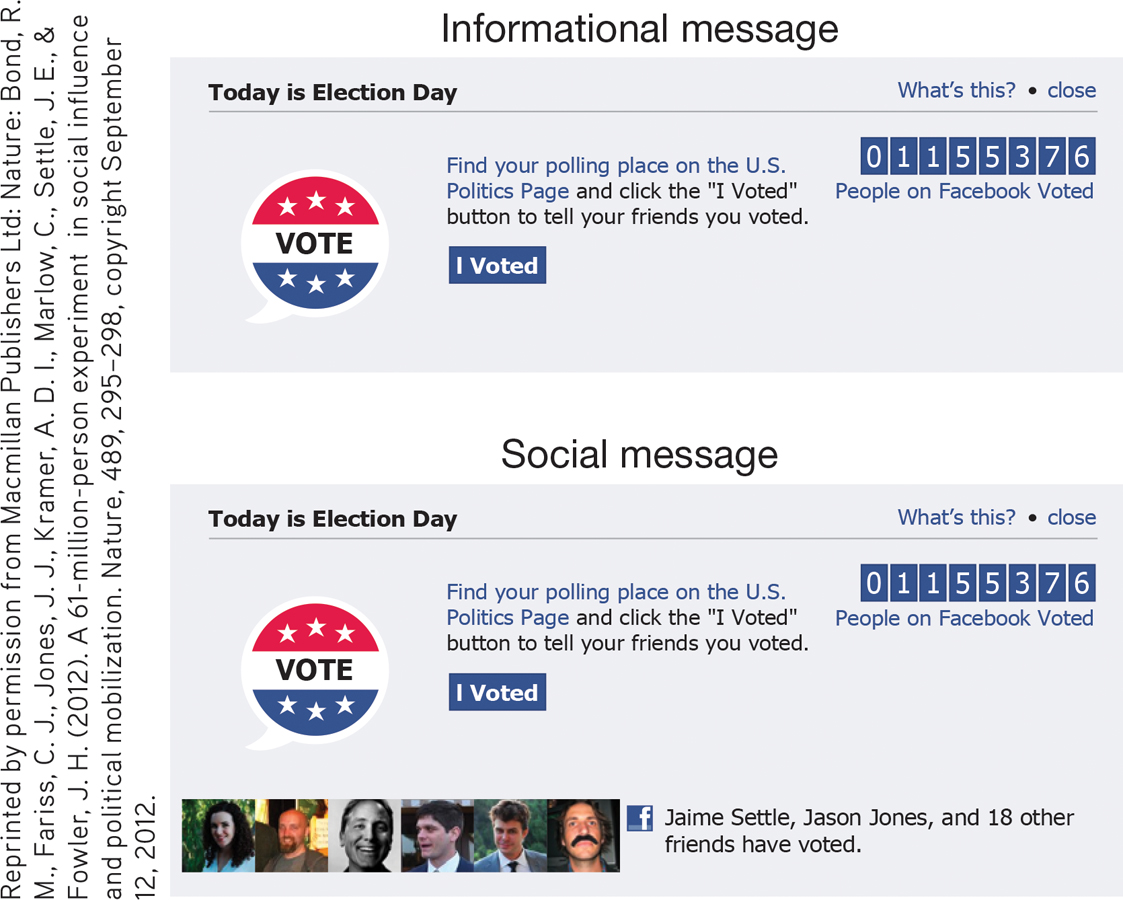

Figure 43.1

Figure 43.1Social networking influence On the 2010 U.S. congressional election day, Facebook gave people an informational message that encouraged voting. The message had measurably more influence when supplemented with a social message that showed friends who had voted (Bond et al., 2012).

Automatic mimicry helps us to empathize—to feel what others are feeling. This helps explain why we feel happier around happy people than around depressed people. It also helps explain why studies of groups of British workers have revealed mood linkage, or the sharing of moods (Totterdell et al., 1998). Empathic people yawn more after seeing others yawn (Morrison, 2007). And empathic mimicking fosters fondness (van Baaren et al., 2003, 2004). Perhaps you’ve noticed that when someone nods their head as you do and echoes your words, you feel a certain rapport and liking?

“When I see synchrony and mimicry—whether it concerns yawning, laughing, dancing, or aping—I see social connection and bonding.”

Primatologist Frans de Waal “The Empathy Instinct,” 2009

Suggestibility and mimicry sometimes lead to tragedy. In the eight days following the 1999 shooting rampage at Colorado’s Columbine High School, every U.S. state except Vermont experienced threats of copycat violence. Pennsylvania alone recorded 60 such threats (Cooper, 1999). Sociologist David Phillips and his colleagues (1985, 1989) found that suicides, too, sometimes increase following a highly publicized suicide. In the wake of screen idol Marilyn Monroe’s suicide on August 5, 1962, for example, the number of suicides in the United States exceeded the usual August count by 200.

What causes behavior clusters? Do people act similarly because of their influence on one another? Or because they are simultaneously exposed to the same events and conditions? Seeking answers to such questions, social psychologists have conducted experiments on group pressure and conformity.

Conformity and Social Norms

Suggestibility and mimicry are subtle types of conformity—adjusting our behavior or thinking toward some group standard. To study conformity, Solomon Asch (1955) devised a simple test. Imagine yourself as a participant in what you believe is a study of visual perception. You arrive in time to take a seat at a table with five other people. The experimenter asks the group to state, one by one, which of three comparison lines is identical to a standard line. You see clearly that the answer is Line 2, and you await your turn to say so. Your boredom begins to show when the next set of lines proves equally easy.

Now comes the third trial, and the correct answer seems just as clear-

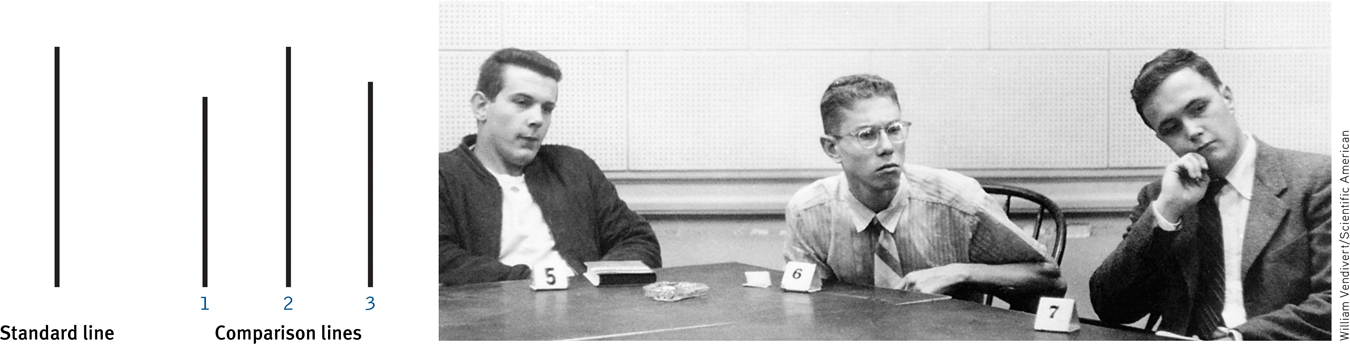

Figure 43.2

Figure 43.2Asch’s conformity experiments Which of the three comparison lines is equal to the standard line? What do you suppose most people would say after hearing five others say, “Line 3”? In this photo from one of Asch’s experiments, the student in the center shows the severe discomfort that comes from disagreeing with the responses of other group members (in this case, accomplices of the experimenter).

In Asch’s experiments, college students, answering questions alone, erred less than 1 percent of the time. But what about when several others—

Later investigations have not always found as much conformity as Asch found, but they have revealed that we are more likely to conform when we

- are made to feel incompetent or insecure.

- are in a group with at least three people.

- are in a group in which everyone else agrees. (If just one other person disagrees, the odds of our disagreeing greatly increase.)

- admire the group’s status and attractiveness.

- have not made a prior commitment to any response.

- know that others in the group will observe our behavior.

- are from a culture that strongly encourages respect for social standards.

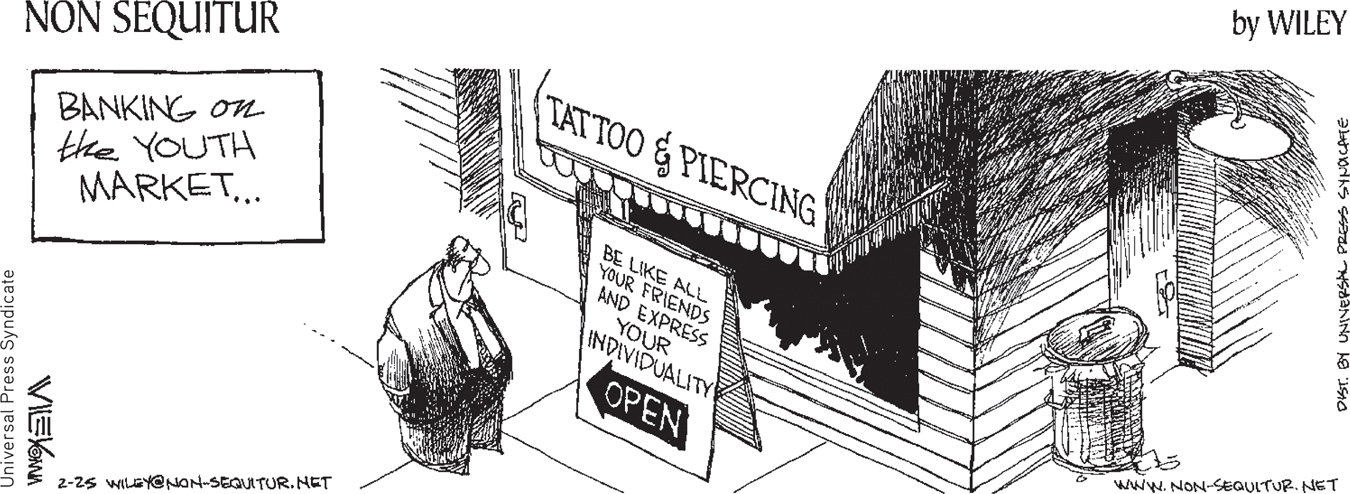

Why do we so often think what others think and do what they do? Why, in college residence halls, do students’ attitudes become more similar to those living near them (Cullum & Harton, 2007)? Why, when asked controversial questions, are students’ answers more diverse when using anonymous electronic clickers than when raising hands (Stowell et al., 2010)? Why do we clap when others clap, eat as others eat, believe what others believe, say what others say, even see what others see?

Frequently, we conform to avoid rejection or to gain social approval. In such cases, we are responding to normative social influence. We are sensitive to social norms—understood rules for accepted and expected behavior—

At other times, we conform because we want to be accurate. Groups provide information, and only an uncommonly stubborn person will never listen to others. “Those who never retract their opinions love themselves more than they love truth,” observed Joseph Joubert, an eighteenth-

Like humans, migrating and herding animals conform for both informational and normative reasons (Claidière & Whiten, 2012). Following others is informative; compared with solo geese, a flock of geese migrate more accurately. (There is wisdom in the crowd.) But staying with the herd also sustains group membership.

Is conformity good or bad? The answer depends partly on our culturally influenced values. Western Europeans and people in most English-

To review the classic conformity studies and experience a simulated experiment, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Everybody’s Doing It!

To review the classic conformity studies and experience a simulated experiment, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Everybody’s Doing It!

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Which of the following strengthens conformity to a group?

- Finding the group attractive

- Feeling secure

- Coming from an individualist culture

- Having made a prior commitment

a