43.2 Obedience: Following Orders

43-

Social psychologist Stanley Milgram (1963, 1974), a high school classmate of Philip Zimbardo and then a student of Solomon Asch, knew that people often give in to social pressures. But how would they respond to outright commands? To find out, he undertook what became social psychology’s most famous and controversial experiments (Benjamin & Simpson, 2009).

Imagine yourself as one of the nearly 1000 people who took part in Milgram’s 20 experiments. You respond to an advertisement for participants in a Yale University psychology study of the effect of punishment on learning. Professor Milgram’s assistant asks you and another person to draw slips from a hat to see who will be the “teacher” and who will be the “learner.” Because (unknown to you) both slips say “teacher,” you draw a “teacher” slip and are asked to sit down in front of a machine, which has a series of labeled switches. The supposed learner, a mild and submissive-

The experiment begins, and you deliver the shocks after the first and second wrong answers. If you continue, you hear the learner grunt when you flick the third, fourth, and fifth switches. After you activate the eighth switch (“120 Volts—

If you obey, you hear the learner shriek in apparent agony as you continue to raise the shock level after each new error. After the 330-

Would you follow the experimenter’s commands to shock someone? At what level would you refuse to obey? Before undertaking the experiments, Milgram asked people what they would do. Most people were sure they would stop soon after the learner first indicated pain, certainly before he shrieked in agony. Forty psychiatrists agreed with that prediction when Milgram asked them. Were the predictions accurate? Not even close. When Milgram conducted the experiment with other men aged 20 to 50, he was astonished. More than 60 percent complied fully—

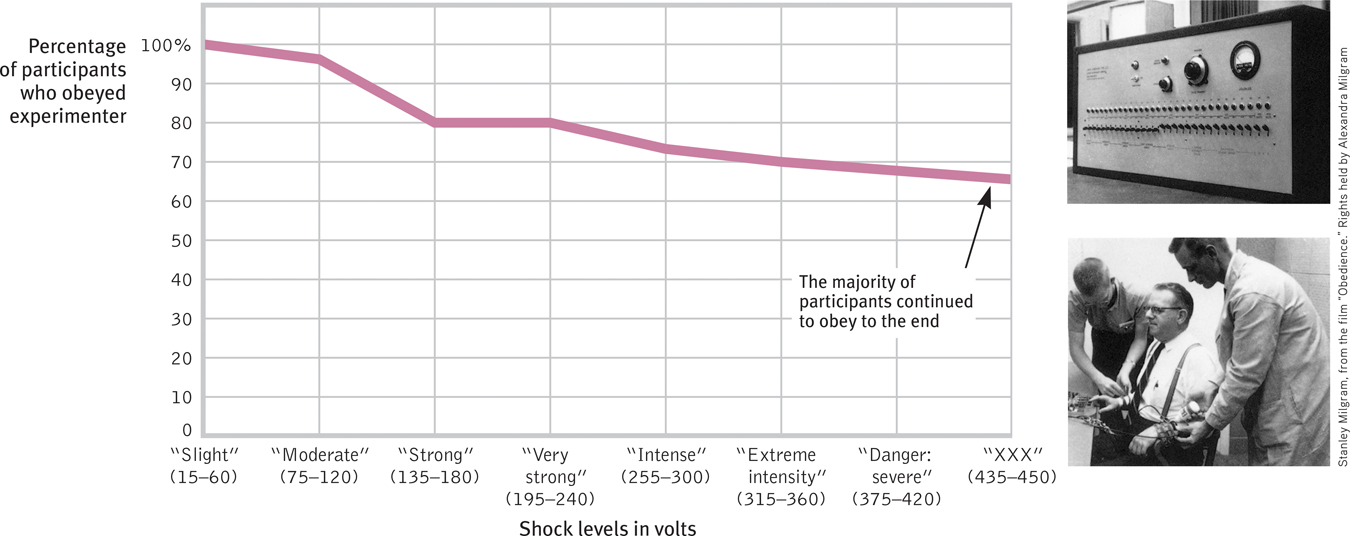

Figure 43.3

Figure 43.3Milgram’s follow-

Cultures change over time. Researchers wondered if Milgram’s results could be explained by the 1960s American mind-

Did Milgram’s teachers figure out the hoax—

Milgram’s use of deception and stress triggered a debate over his research ethics. In his own defense, Milgram pointed out that, after the participants learned of the deception and actual research purposes, virtually none regretted taking part (though perhaps by then the participants had reduced their cognitive dissonance—the discomfort they felt when their actions conflicted with their attitudes). When 40 of the teachers who had agonized most were later interviewed by a psychiatrist, none appeared to be suffering emotional aftereffects. All in all, said Milgram, the experiments provoked less enduring stress than university students experience when facing and failing big exams (Blass, 1996). Other scholars, however, after delving into Milgram’s archives, report that his debriefing was less extensive and his participants’ distress greater than what he had suggested (Nicholson, 2011; Perry, 2013).

In later experiments, Milgram discovered some conditions that influence people’s behavior. When he varied the situation, the percentage of participants who obeyed fully ranged from 0 to 93 percent. Obedience was highest when

- the person giving the orders was close at hand and was perceived to be a legitimate authority figure. Such was the case in 2005 when Temple University’s basketball coach sent a 250-pound bench player, Nehemiah Ingram, into a game with instructions to commit “hard fouls.” Following orders, Ingram fouled out in four minutes after breaking an opposing player’s right arm.

- the authority figure was supported by a prestigious institution. Compliance was somewhat lower when Milgram dissociated his experiments from Yale University. People have wondered: Why, during the 1994 Rwandan genocide, did so many Hutu citizens slaughter their Tutsi neighbors? It was partly because they were part of “a culture in which orders from above, even if evil,” were understood as having the force of law (Kamatali, 2014).

- the victim was depersonalized or at a distance, even in another room. Similarly, many soldiers in combat either have not fired their rifles at an enemy they can see, or have not aimed them properly. Such refusals to kill have been rare among soldiers who were operating long-distance artillery or aircraft weapons (Padgett, 1989). Those who killed from a distance—by operating remotely piloted drones—also have suffered much less posttraumatic stress than have on-the-ground Afghanistan and Iraq War veterans (Miller, 2012).Page 530

Standing up for democracy Some individuals—roughly one in three in Milgram’s experiments—resist social coercion, as did this unarmed man in Beijing, by single-handedly challenging an advancing line of tanks the day after the 1989 Tiananmen Square student uprising was suppressed.

Standing up for democracy Some individuals—roughly one in three in Milgram’s experiments—resist social coercion, as did this unarmed man in Beijing, by single-handedly challenging an advancing line of tanks the day after the 1989 Tiananmen Square student uprising was suppressed. - there were no role models for defiance. “Teachers” did not see any other participant disobey the experimenter.

The power of legitimate, close-

The commander gave the recruits a chance to refuse to participate in the executions. Only about a dozen immediately refused. Within 17 hours, the remaining 485 officers killed 1500 helpless women, children, and elderly, shooting them in the back of the head as they lay face down. Hearing the victims’ pleas, and seeing the gruesome results, some 20 percent of the officers did eventually dissent, managing either to miss their victims or to wander away and hide until the slaughter was over (Browning, 1992). In real life, as in Milgram’s experiments, those who resisted did so early, and they were the minority.

A different story played out in the French village of Le Chambon. There, villagers openly defied orders to cooperate with the “New Order” by sheltering French Jews, who were destined for deportation to Germany. The villagers’ Protestant ancestors had themselves been persecuted, and their pastors taught them to “resist whenever our adversaries will demand of us obedience contrary to the orders of the Gospel” (Rochat, 1993). Ordered by police to give a list of sheltered Jews, the head pastor modeled defiance: “I don’t know of Jews, I only know of human beings.” Without realizing how long and terrible the war would be, or how much punishment and poverty they would suffer, the resisters made an initial commitment to resist. Supported by their beliefs, their role models, their interactions with one another, and their own initial acts, they remained defiant to the war’s end.

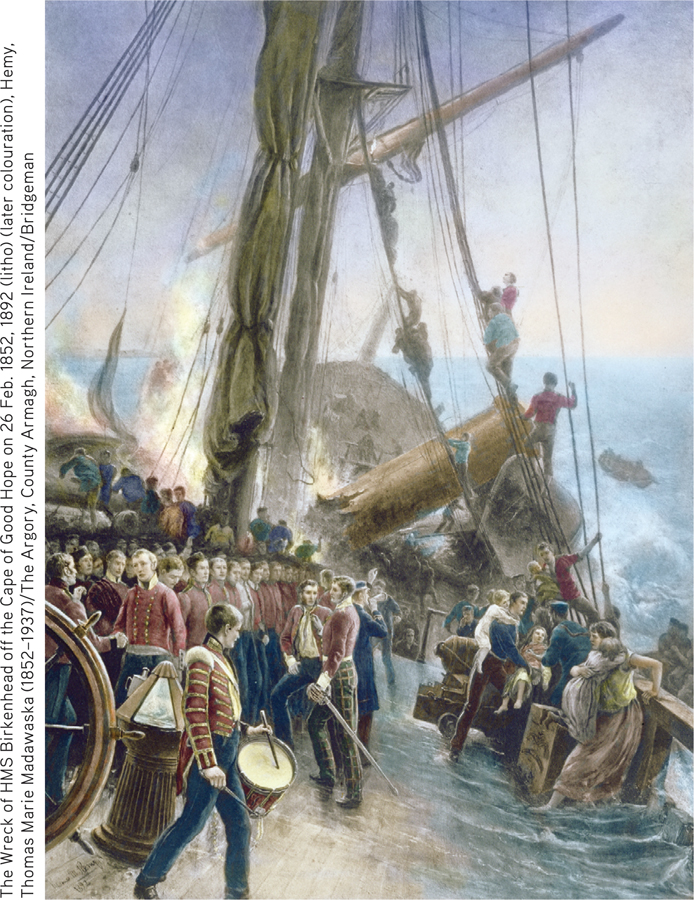

Lest we presume that obedience is always evil and resistance is always good, consider the obedience of British soldiers who, in 1852, were traveling with civilians aboard the steamship Birkenhead. As they neared their South African port, the Birkenhead became impaled on a rock. To calm the passengers and permit an orderly exit of civilians on the three available lifeboats, soldiers who were not assisting the passengers or working the pumps lined up at parade rest. “Steady, men!” said their officer as the lifeboats pulled away. Heroically, no one frantically rushed to claim a lifeboat seat. As the boat sank, all were plunged into the sea, most to be drowned or devoured by sharks. For almost a century, noted James Michener (1978), “the Birkenhead drill remained the measure by which heroic behavior at sea was measured.”

Lessons From the Obedience Studies

What do the Milgram experiments teach us about ourselves? How does flicking a shock switch relate to everyday social behavior? Psychological experiments aim not to re-

In Milgram’s experiments and their modern replications, participants were torn. Should they respond to the pleas of the victim or the orders of the experimenter? Their moral sense warned them not to harm another, yet it also prompted them to obey the experimenter and to be a good research participant. With kindness and obedience on a collision course, obedience usually won.

These experiments demonstrated that strong social influences can make people conform to falsehoods or capitulate to cruelty. Milgram saw this as the fundamental lesson of this work: “Ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process” (1974, p. 6).

“I was only following orders.”

Adolf Eichmann, Director of Nazi deportation of Jews to concentration camps

Focusing on the end point—

“All evil begins with 15 volts.”

Philip Zimbardo, Stanford lecture, 2010

So it happens when people succumb, gradually, to evil. In any society, great evils often grow out of people’s compliance with lesser evils. The Nazi leaders suspected that most German civil servants would resist shooting or gassing Jews directly, but they found them surprisingly willing to handle the paperwork of the Holocaust (Silver & Geller, 1978). Milgram found a similar reaction in his experiments. When he asked 40 men to administer the learning test while someone else did the shocking, 93 percent complied. Cruelty does not require devilish villains. All it takes is ordinary people corrupted by an evil situation. Ordinary students may follow orders to haze initiates into their group. Ordinary employees may follow orders to produce and market harmful products. Ordinary soldiers may follow orders to punish and then torture prisoners (Lankford, 2009).

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Psychology’s most famous obedience experiments, in which most participants obeyed an authority figure’s demands to inflict presumed painful, dangerous shocks on an innocent participant, were conducted by social psychologist __________ __________.

Stanley Milgram

- What situations have researchers found to be most likely to encourage obedience in participants?

The Milgram studies showed that people were most likely to follow orders when the experimenter was nearby and was a legitimate authority figure, the victim was not nearby, and there were no models for defiance.