43.3 Group Behavior

43-

Imagine standing in a room, holding a fishing pole. Your task is to wind the reel as fast as you can. On some occasions you wind in the presence of another participant, who is also winding as fast as possible. Will the other’s presence affect your own performance?

In one of social psychology’s first experiments, Norman Triplett (1898) reported that adolescents would wind a fishing reel faster in the presence of someone doing the same thing. Although a modern reanalysis revealed that the difference was modest (Stroebe, 2012), Triplett inspired later social psychologists to study how others’ presence affects our behavior. Group influences operate both in simple groups—

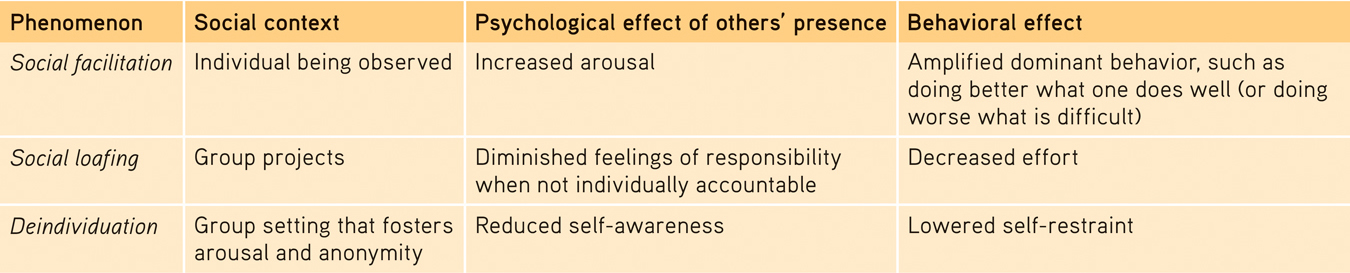

Social Facilitation

Triplett’s claim—

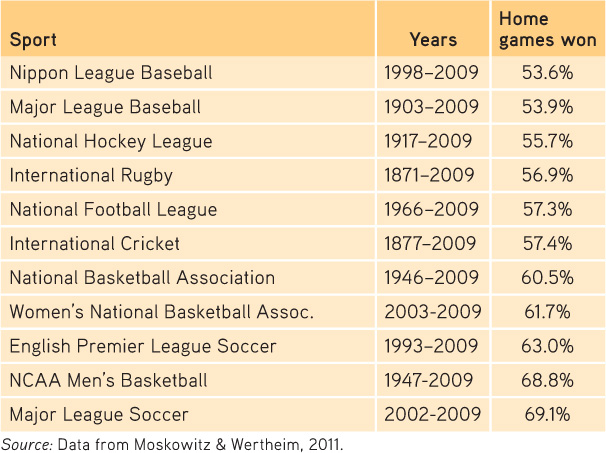

The energizing effect of an enthusiastic audience probably contributes to the home advantage that has shown up in studies of more than a quarter-

Table 43.1

Table 43.1Home Advantage in Team Sports

Social facilitation also helps explain a funny effect of crowding. Comedians and actors know that a “good house” is a full one. Crowding triggers arousal. Comedy routines that are mildly amusing in an uncrowded room seem funnier in a densely packed room (Aiello et al., 1983; Freedman & Perlick, 1979). In experiments, when seated close to one another, participants like a friendly person even more and an unfriendly person even less (Schiffenbauer & Schiavo, 1976; Storms & Thomas, 1977). So, to ensure an energetic class or event, choose a room or set up seating that will just barely accommodate everyone.

The point to remember: What you do well, you are likely to do even better in front of an audience, especially a friendly audience. What you normally find difficult may seem all but impossible when you are being watched.

Social Loafing

Social facilitation experiments test the effect of others’ presence on performance of an individual task, such as shooting pool. But what happens when people perform as a group? In a team tug-

To find out, a University of Massachusetts research team asked blindfolded students “to pull as hard as you can” on a rope. When they fooled the students into believing three others were also pulling behind them, students exerted only 82 percent as much effort as when they knew they were pulling alone (Ingham et al., 1974). And consider what happened when blindfolded people seated in a group clapped or shouted as loudly as they could while hearing (through headphones) other people clapping or shouting loudly (Latané, 1981). When they thought they were part of a group effort, the participants produced about one-

Bibb Latané and his colleagues (1981; Jackson & Williams, 1988) described this diminished effort as social loafing. Experiments in the United States, India, Thailand, Japan, China, and Taiwan have found social loafing on various tasks, though it was especially common among men in individualist cultures (Karau & Williams, 1993). What causes social loafing? Three things:

- People acting as part of a group feel less accountable, and therefore worry less about what others think.

- Group members may view their individual contributions as dispensable (Harkins & Szymanski, 1989; Kerr & Bruun, 1983).

- When group members share equally in the benefits, regardless of how much they contribute, some may slack off (as you perhaps have observed on group assignments). Unless highly motivated and strongly identified with the group, people may free ride on others’ efforts.

Deindividuation

We’ve seen that the presence of others can arouse people (social facilitation), or it can diminish their feelings of responsibility (social loafing). But sometimes the presence of others does both. The uninhibited behavior that results can range from a food fight to vandalism or rioting. This process of losing self-

Deindividuation thrives, for better or for worse, in many settings. Tribal warriors who depersonalize themselves with face paints or masks are more likely than those with exposed faces to kill, torture, or mutilate captured enemies (Watson, 1973). On discussion boards, Internet bullies, who would never say “You’re so fake” to someone’s face, may hide behind anonymity. When we shed self-

Table 43.2

Table 43.2Behavior in the Presence of Others: Three Phenomena

***

We have examined the conditions under which the presence of others can motivate people to exert themselves or tempt them to free ride on the efforts of others, make easy tasks easier and difficult tasks harder, and enhance humor or fuel mob violence. Research also shows that interacting with others can similarly have both bad and good effects.

Group Polarization

43-

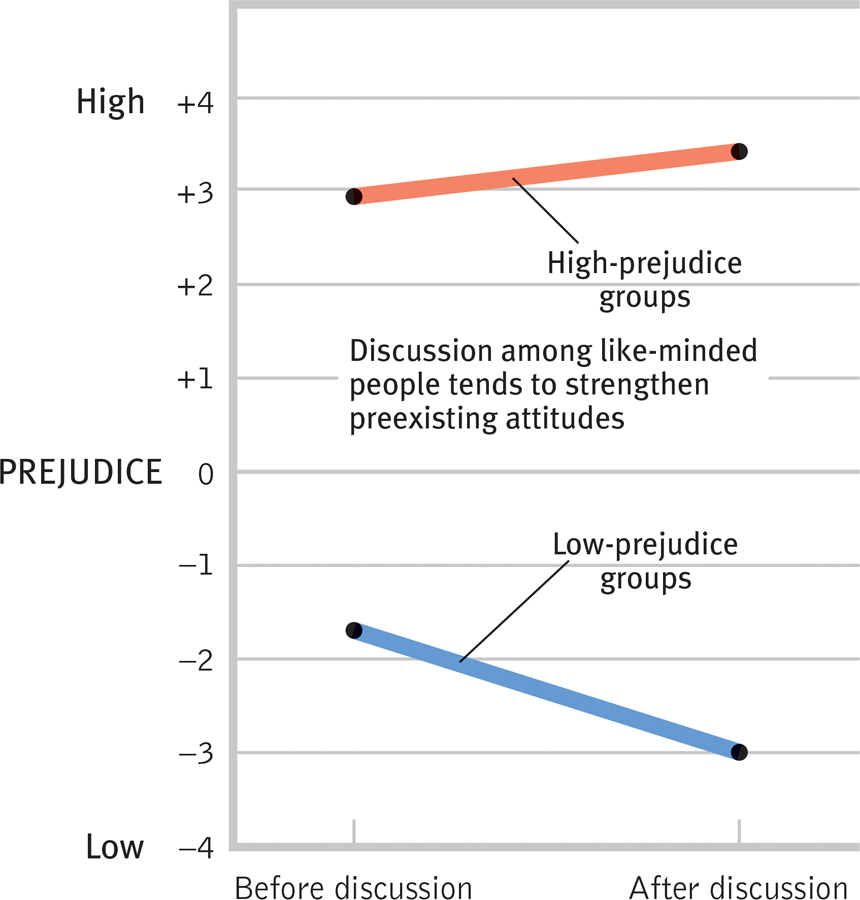

Over time, initial differences between groups of college students tend to grow. If the first-

In each case, the beliefs and attitudes we bring to a group grow stronger as we discuss them with like-

Figure 43.4

Figure 43.4Group polarization If a group is like-

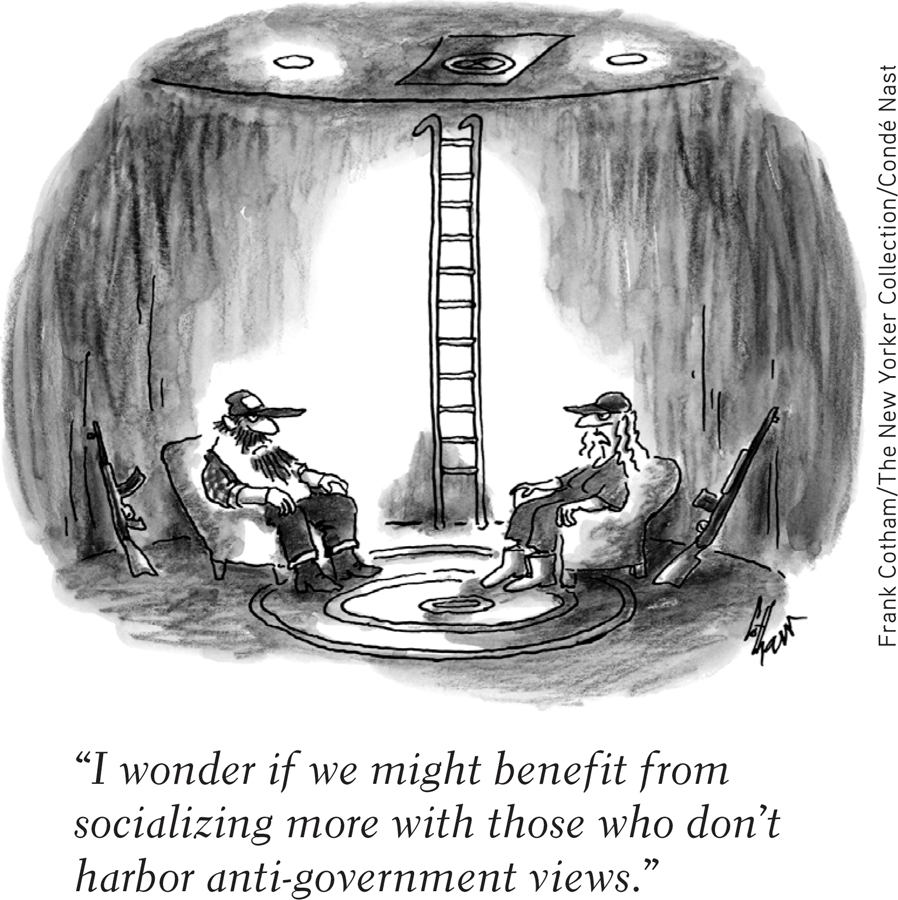

Group polarization can feed extremism and even suicide terrorism. Analyses of terrorist organizations around the world reveal that the terrorist mentality does not erupt suddenly, on a whim (McCauley, 2002; McCauley & Segal, 1987; Merari, 2002). It usually begins slowly, among people who share a grievance. As they interact in isolation (sometimes with other “brothers” and “sisters” in camps) their views grow more and more extreme. Increasingly, they categorize the world as “us” against “them” (Moghaddam, 2005; Qirko, 2004). Given that the self-

“What explains the rise of fascism in the 1930s? The emergence of student radicalism in the 1960s? The growth of Islamic terrorism in the 1990s?… The unifying theme is simple: When people find themselves in groups of like-minded types, they are especially likely to move to extremes. [This] is the phenomenon of group polarization.”

Cass Sunstein, Going to Extremes, 2009

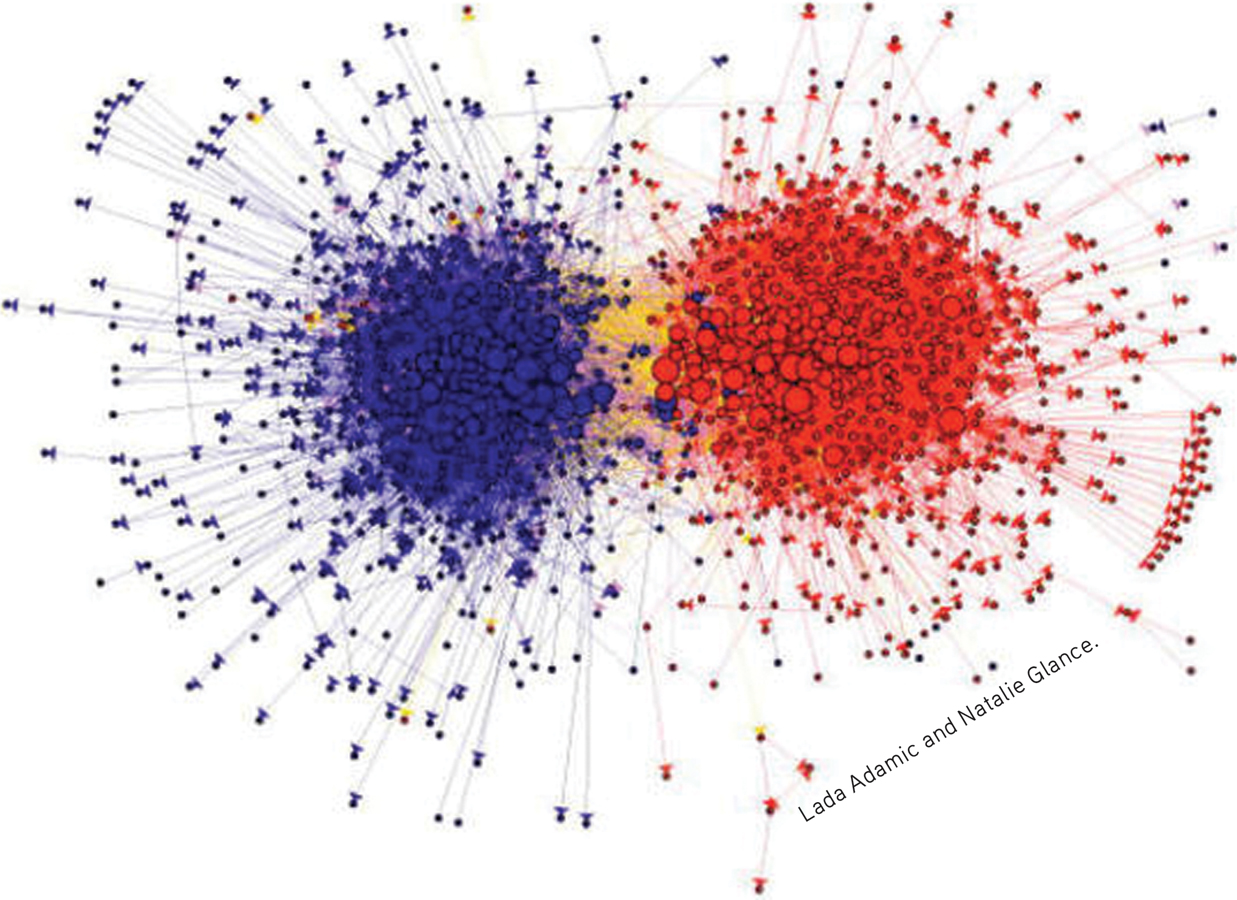

When I got my start in social psychology with experiments on group polarization, I never imagined the potential dangers, or the creative possibilities, of polarization in virtual groups. Electronic communication and social networking have created virtual town halls where people can isolate themselves from those with different perspectives. By attuning our bookmarks and social media feeds to sites that trash the views we despise, we can retreat into partisan tribes and revel in foregone conclusions. People read blogs that reinforce their views, and those blogs link to kindred blogs (FIGURE 43.5). Over time, the resulting political polarization—

Figure 43.5

Figure 43.5Like minds network in the blogosphere Blue liberal blogs link mostly to one another, as do red conservative blogs. (The intervening colors display links across the liberal-

As the Internet connects the like-

But the Internet-

The point to remember: By connecting and magnifying the inclinations of like-

Groupthink

“One of the dangers in the White House, based on my reading of history, is that you get wrapped up in groupthink and everybody agrees with everything, and there’s no discussion and there are no dissenting views.”

Barack Obama, December 1, 2008, press conference

So, group interaction can influence our personal decisions. Does it ever distort important national decisions? Consider the “Bay of Pigs fiasco.” In 1961, President John F. Kennedy and his advisers decided to invade Cuba with 1400 CIA-

Social psychologist Irving Janis (1982) studied the decision-

“Truth springs from argument among friends.”

Philosopher David Hume, 1711–1776

Later studies showed that groupthink—

“If you have an apple and I have an apple and we exchange apples then you and I will still each have one apple. But if you have an idea and I have an idea and we exchange these ideas, then each of us will have two ideas.”

Attributed to dramatist George Bernard Shaw, 1856–1950

Despite the dangers of groupthink, two heads are often better than one. Knowing this, Janis also studied instances in which U.S. presidents and their advisers collectively made good decisions, such as when the Truman administration formulated the Marshall Plan, which offered assistance to Europe after World War II, and when the Kennedy administration successfully prevented the Soviets from installing missiles in Cuba. In such instances—

The Power of Individuals

In affirming the power of social influence, we must not overlook the power of individuals. Social control (the power of the situation) and personal control (the power of the individual) interact. People aren’t billiard balls. When feeling coerced, we may react by doing the opposite of what is expected, thereby reasserting our sense of freedom (Brehm & Brehm, 1981).

Committed individuals can sway the majority and make social history. Were this not so, communism would have remained an obscure theory, Christianity would be a small Middle Eastern sect, and Rosa Parks’ refusal to sit at the back of the bus would not have ignited the U.S. civil rights movement. Technological history, too, is often made by innovative minorities who overcome the majority’s resistance to change. To many, the railroad was a nonsensical idea; some farmers even feared that train noise would prevent hens from laying eggs. People derided Robert Fulton’s steamboat as “Fulton’s Folly.” As Fulton later said, “Never did a single encouraging remark, a bright hope, a warm wish, cross my path.” Much the same reaction greeted the printing press, the telegraph, the incandescent lamp, and the typewriter (Cantril & Bumstead, 1960).

The power of one or two individuals to sway majorities is minority influence (Mosco-

The bottom line: The powers of social influence are enormous, but so are the powers of the committed individual. For classical music, Mozart mattered. For drama, Shakespeare mattered. For world history, Hitler and Mao—

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is social facilitation, and why is it more likely to occur with a well-learned task?

This improved performance in the presence of others is most likely to occur with a well-

- People tend to exert less effort when working with a group than they would alone, which is called ______________ ______________.

social loafing

- You are organizing a meeting of fiercely competitive political candidates. To add to the fun, friends have suggested handing out masks of the candidates’ faces for supporters to wear. What phenomenon might these masks engage?

The anonymity provided by the masks, combined with the arousal of the contentious setting, might create deindividuation (lessened self-

- When like-minded groups discuss a topic, and the result is the strengthening of the prevailing opinion, this is called ______________ ______________.

group polarization

- When a group’s desire for harmony overrides its realistic analysis of other options, __________ has occurred.

groupthink