44.1 Prejudice

44-

Prejudice means “prejudgment.” It is an unjustifiable and usually negative attitude toward a group—

- beliefs (in this case, called stereotypes).

- emotions (for example, hostility or fear).

- predispositions to action (to discriminate).

Some stereotypes may be at least partly accurate. If you presume that young men tend to drive faster than elderly women, you may be right. People perceive Australians as having a rougher culture than the British, and in one analysis of millions of Facebook status updates, Australians did use more profanity (Kramer & Chung, 2011). But stereotypes can exaggerate—

How Prejudiced Are People?

Prejudice comes as both explicit (overt) and implicit (automatic) attitudes toward people of a particular ethnic group, gender, sexual orientation, or viewpoint. Some examples:

Explicit Ethnic PrejudiceAmericans’ expressed racial attitudes have changed dramatically in the last half-

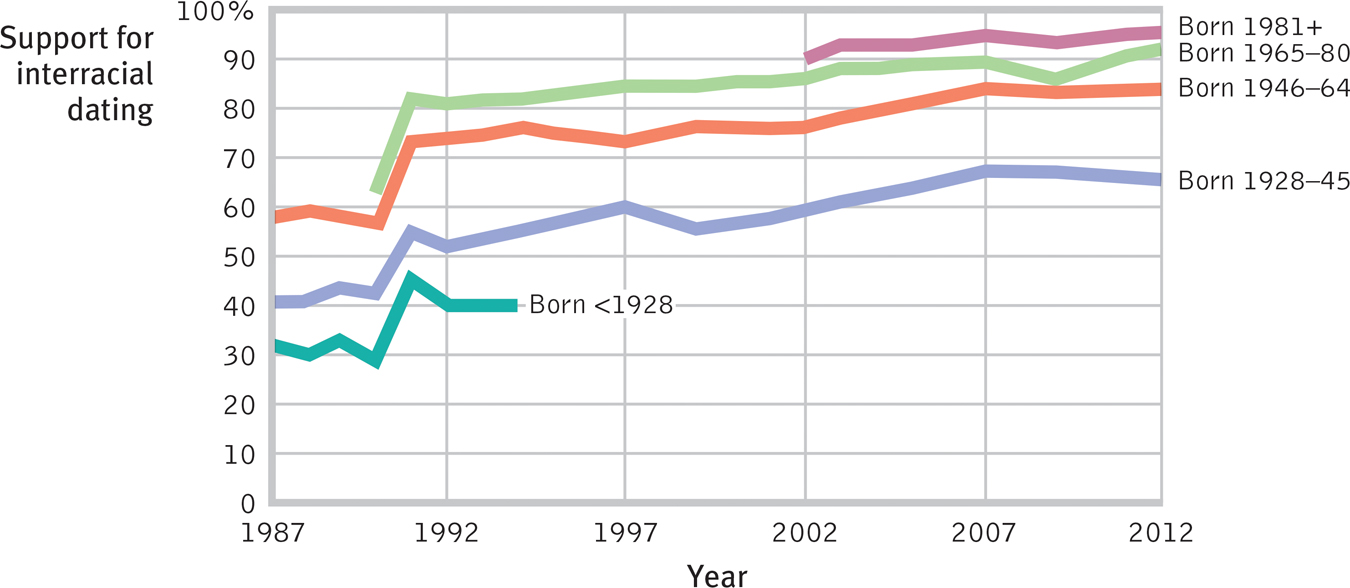

Figure 44.1

Figure 44.1Prejudice over time Over the last quarter-

Yet as overt prejudice wanes, subtle prejudice lingers. Despite increased verbal support for interracial marriage, many people admit that in socially intimate settings (dating, dancing, marrying) they, personally, would feel uncomfortable with someone of another race. And many people who say they would feel upset with someone making racist slurs actually, when hearing such racism, respond indifferently (Kawakami et al., 2009). Subtle prejudice may also take the form of “microaggressions,” such as race-

Nevertheless, overt prejudice persists. In the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, 4 in 10 Americans acknowledged “some feelings of prejudice against Muslims,” and about half of non-

“Unhappily, the world has yet to learn how to live with diversity.”

Pope John Paul II, Address to the United Nations, 1995

Implicit PrejudiceAs we have seen throughout this book, the human mind processes thoughts, memories, and attitudes on two different tracks. Sometimes that processing is explicit—on the radar screen of our awareness. To a much greater extent, it is implicit—below the radar, leaving us unaware of how our attitudes are influencing our behavior. Modern studies indicate that prejudice is often implicit, an automatic attitude—

Implicit racial associations Using Implicit Association Tests, researchers have demonstrated that even people who deny harboring racial prejudice may carry negative associations (Banaji & Greenwald, 2013). (By 2014, about 16 million people had taken the Implicit Association Test, as you can at www.implicit.harvard.edu.) For example, 9 in 10 White respondents took longer to identify pleasant words (such as peace and paradise) as “good” when presented with Black-

Although the test is useful for studying automatic prejudice, critics caution against using it to assess or label individuals (Oswald et al., 2013). Defenders counter that implicit biases predict behaviors ranging from simple acts of friendliness to the evaluation of work quality (Banaji & Greenwald, 2013). In the 2008 U.S. presidential election, implicit as well as explicit prejudice predicted voters’ support for candidate Barack Obama, whose election in turn served to reduce implicit prejudice (Bernstein et al., 2010; Payne et al., 2010; Stephens-

To take one version of the Implicit Associations Test, visit LaunchPad’s Lab: Stereotyping.

To take one version of the Implicit Associations Test, visit LaunchPad’s Lab: Stereotyping.

Unconscious patronization In one experiment, White university women assessed flawed student essays. When assessing essays supposedly written by White students, the women gave low evaluations, often with harsh comments, but not so when the essays were said to have been written by Black students (Harber, 1998). Did the evaluators calibrate their evaluations to their racial stereotypes, leading to less exacting standards and a patronizing attitude? In real-

Race-influenced perceptions Our expectations influence our perceptions. In 1999, Amadou Diallo was accosted as he approached his apartment house doorway by police officers looking for a rapist. When he pulled out his wallet, the officers, perceiving a gun, riddled his body with 19 bullets from 41 shots. Curious about this tragic killing of an unarmed, innocent man, two research teams reenacted the situation (Correll et al., 2002, 2007; Greenwald et al., 2003; Sadler et al., 2012). They asked viewers to press buttons quickly to “shoot” or not shoot men who suddenly appeared on screen. Some of the on-

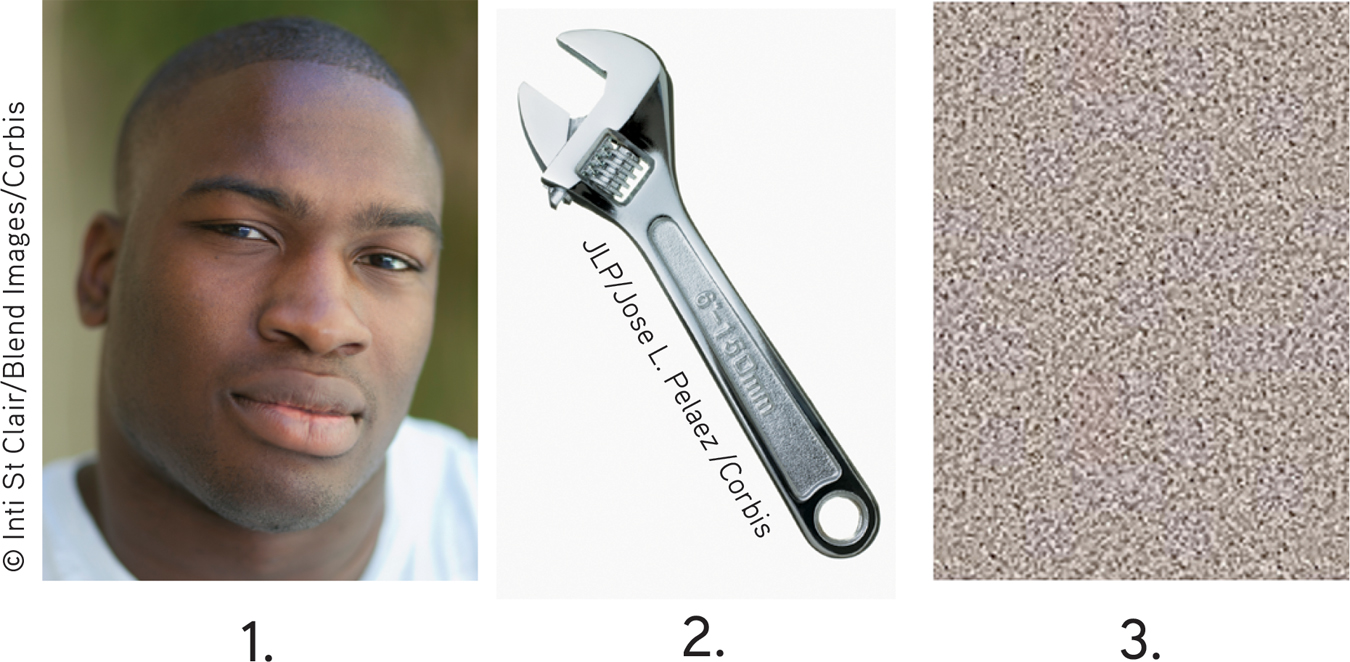

Figure 44.2

Figure 44.2Race primes perceptions In experiments by Keith Payne (2006), people viewed (1) a White or Black face, immediately followed by (2) a gun or hand tool, which was then followed by (3) a visual mask. Participants were more likely to misperceive a tool as a gun when it was preceded by a Black rather than White face.

Does this automatic racial bias research help us understand the 2013 death of Trayvon Martin? As he walked alone to his father’s fiancée’s house in a gated Florida neighborhood, a suspicious resident started following him, leading to a confrontation and to Martin’s being shot dead. Commentators wondered: Had Martin been an unarmed White teen, would he have been perceived and treated the same way?

Reflexive bodily responses Even people who consciously express little prejudice may give off telltale signals as their body responds selectively to another’s race. Neuroscientists can detect these signals when people look at White and Black faces. The viewers’ implicit prejudice may show up in facial-

If your own gut-

Gender PrejudiceOvert gender prejudice has also declined sharply. The one-

But gender prejudice and discrimination persist. Despite equality between the sexes in intelligence scores, people have tended to perceive their fathers as more intelligent than their mothers (Furnham & Wu, 2008). In Saudi Arabia, women have not been allowed to drive. In Western countries, we pay more to those (usually men) who care for our streets than to those (usually women) who care for our children. Worldwide, women are more likely to live in poverty (UN, 2010); they represent nearly two-

Unwanted female infants are no longer left out on a hillside to die of exposure, as was the practice in ancient Greece. Yet natural female mortality and the normal male-

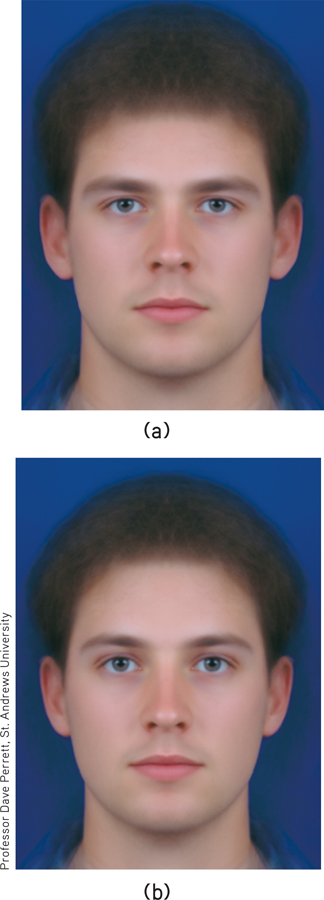

Studies have shown, however, that most people feel more positively about women in general than they do about men (Eagly, 1994; Haddock & Zanna, 1994). Worldwide, people see women as having some traits (such as nurturance, sensitivity, and less aggressiveness) that most people prefer (Glick et al., 2004; Swim, 1994). That may explain why women tend to like women more than men like men (Rudman & Goodwin, 2004). And perhaps that is also why people prefer slightly feminized computer-

Figure 44.3

Figure 44.3(1) Who do you like best?

(2) Which one placed an ad seeking “a special lady to love and cherish forever”? (See answers below.)

Research suggests that subtly feminized features convey a likable image, which people tend to associate more with committed dads than with promiscuous cads. Thus, 66 percent of the women picked computer-

Sexual Orientation PrejudiceIn most of the world, gay and lesbian people cannot openly and comfortably disclose who they are and whom they love (Katz-

- In national surveys, 40 percent of LGBT Americans said it would be very or somewhat difficult for someone in their community “to live openly as gay or lesbian” (Jones, 2012). Thirty-nine percent reported having “been rejected by a friend or family member” because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. And 58 percent reported being “subject to slurs or jokes” (Pew, 2013).

- In the National School Climate Survey, 8 of 10 LGBT adolescents reported sexual orientation-related harassment in the prior year (GLSEN, 2012).

Do attitudes and practices that label, disparage, and discriminate against gay and lesbian people increase their risk of psychological disorder and ill health? In U.S. states without protections against LGBT hate crime and discrimination, gay and lesbian people experience substantially higher rates for depression and related disorders, even after controlling for income and education differences. In communities where anti-

Social Roots of Prejudice

Why does prejudice arise? Social inequalities and divisions are partly responsible.

Social InequalitiesWhen some people have money, power, and prestige and others do not, the “haves” usually develop attitudes that justify things as they are. The just-world phenomenon reflects an idea we commonly teach our children—

Victims of discrimination may react with either self-

Us and Them: Ingroup and OutgroupWe have inherited our Stone Age ancestors’ need to belong, to live and love in groups. There was safety in solidarity (those who didn’t band together left fewer descendants). Whether hunting, defending, or attacking, 10 hands were better than 2. Dividing the world into “us” and “them” entails racism and war, but it also provides the benefits of communal solidarity. Thus, we cheer for our groups, kill for them, die for them. Indeed, we define who we are partly in terms of our groups. Through our social identities we associate ourselves with certain groups and contrast ourselves with others (Dunham et al., 2013; Hogg, 1996, 2006; Turner, 1987, 2007). When Ian identifies himself as a man, an Aussie, a University of Sydney student, a Catholic, and a MacGregor, he knows who he is, and so do we.

Evolution prepared us, when encountering strangers, to make instant judgments: friend or foe? Those from our group, those who look like us, and also those who sound like us—

The urge to distinguish enemies from friends predisposes prejudice against strangers (Whitley, 1999). To Greeks of the classical era, all non-

“For if [people were] to choose out of all the customs in the world [they would] end by preferring their own.”

Greek historian Herodotus, 440 b.c.e.

Ingroup bias explains the cognitive power of political partisanship (Cooper, 2010; Douthat, 2010). In the United States in the late 1980s, most Democrats believed inflation had risen under Republican president Ronald Reagan (it had dropped). In 2010, most Republicans believed that taxes had increased under Democratic president Barack Obama (for most, they had decreased).

Emotional Roots of Prejudice

“If the Tiber reaches the walls, if the Nile does not rise to the fields, if the sky doesn’t move or the Earth does, if there is famine, if there is plague, the cry is at once: ‘The Christians to the lion!’’”

Tertullian, Apologeticus, 197 c.e.

Prejudice springs not only from the divisions of society but also from the passions of the heart. Scapegoat theory notes that when things go wrong, finding someone to blame can provide a target for anger. Following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, some outraged people lashed out at innocent Arab-

“The misfortunes of others are the taste of honey.”

Japanese saying

Evidence for the scapegoat theory of prejudice comes from high prejudice among economically frustrated people. And it comes from experiments in which a temporary frustration intensifies prejudice. Students who experience failure or are made to feel insecure often restore their self-

Negative emotions nourish prejudice. When facing death, fearing threats, or experiencing frustration, people cling more tightly to their ingroup and their friends. As terrorism fear heightens patriotism, it also produces loathing and aggression toward “them”—those who threaten our world (Pyszczynski et al., 2002, 2008). The few individuals who lack fear and its associated activity in the emotion-

Cognitive Roots of Prejudice

44-

Prejudice springs from a culture’s divisions, the heart’s passions, and also from the mind’s natural workings. Stereotyped beliefs are a by-

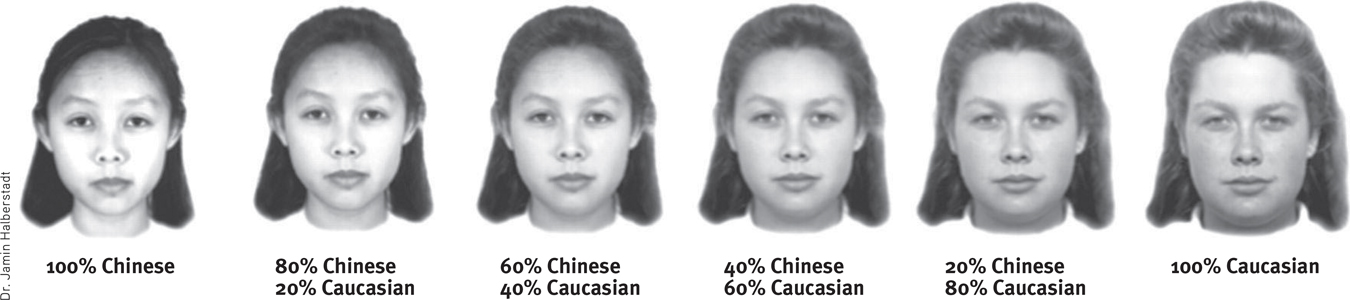

Forming CategoriesOne way we simplify our world is to categorize. A chemist categorizes molecules as organic and inorganic. Therapists categorize psychological disorders. All of us categorize people by race, with mixed-

Figure 44.4

Figure 44.4Categorizing mixed-

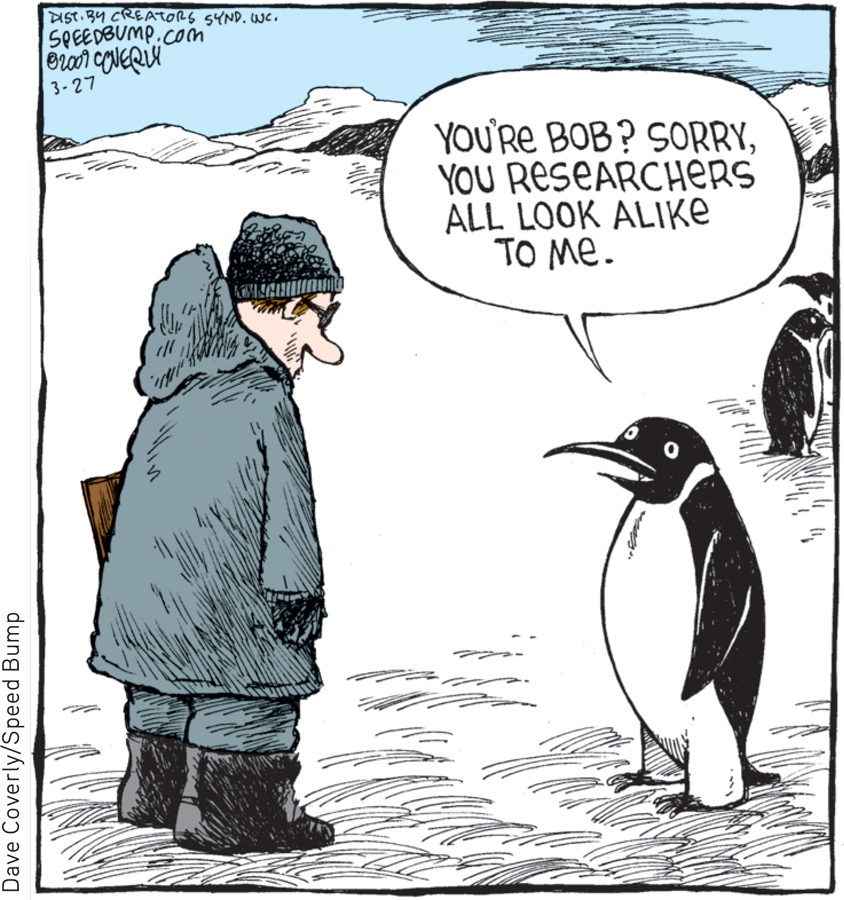

When categorizing people into groups we often stereotype. We recognize how greatly we differ from other individuals in our groups. But we overestimate the homogeneity of other groups (we perceive outgroup homogeneity). “They”—the members of some other group—

With effort and with experience, people get better at recognizing individual faces from another group (Hugenberg et al., 2010; Young et al., 2012). People of European descent, for example, more accurately identify individual African faces if they have watched a great deal of basketball on television, exposing them to many African-

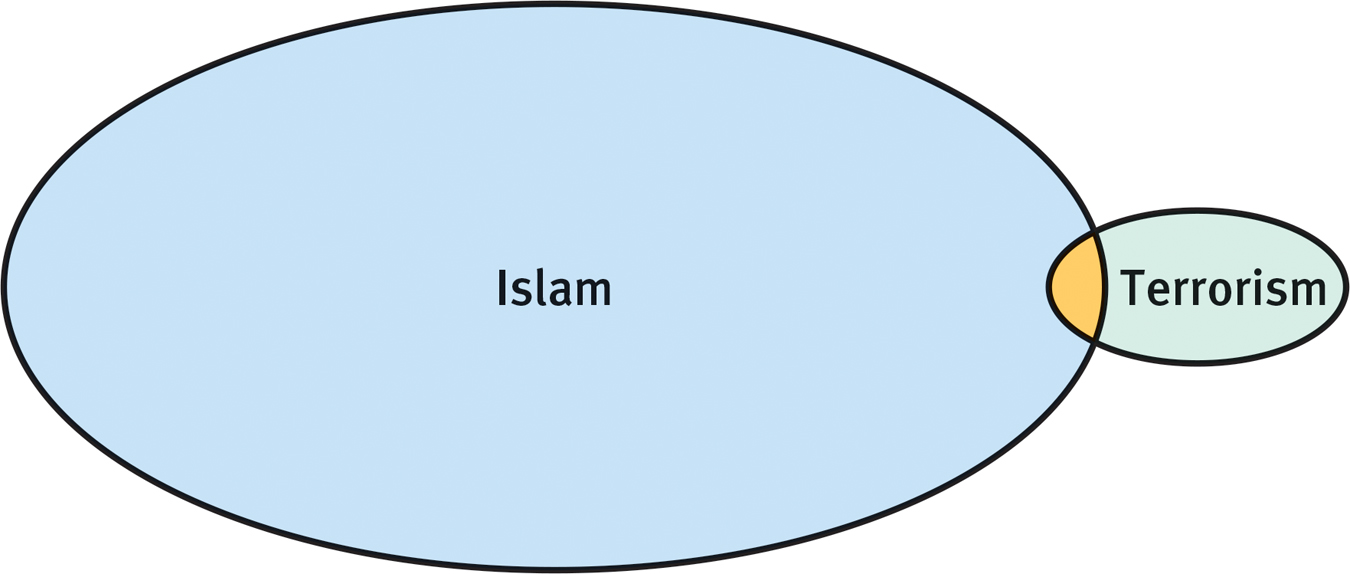

Remembering Vivid CasesWe often judge the frequency of events by instances that readily come to mind. In a classic experiment, researchers showed two groups of University of Oregon students lists containing information about 50 men (Rothbart et al., 1978). The first group’s list included 10 men arrested for nonviolent crimes, such as forgery. The second group’s list included 10 men arrested for violent crimes, such as assault. Later, both groups were asked how many men on their list had committed any sort of crime. The second group overestimated the number. Vivid—

Figure 44.5

Figure 44.5Vivid cases feed stereotypes The 9/11 Muslim terrorists created, in many minds, an exaggerated stereotype of Muslims as terrorism-

To review attribution research and experience a simulation of how stereotypes form, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Not My Type. And for a 6.5-

To review attribution research and experience a simulation of how stereotypes form, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Not My Type. And for a 6.5-

Believing the World Is JustAs we noted earlier, people often justify their prejudices by blaming victims. If the world is just, they assume, people must get what they deserve. As one German civilian is said to have remarked when visiting the Bergen-

Hindsight bias is also at work here (Carli & Leonard, 1989). Have you ever heard people say that rape victims, abused spouses, or people with AIDS got what they deserved? In some countries, such as Pakistan, rape victims have been sentenced to severe punishment for violating adultery prohibitions (Mydans, 2002). In one experiment illustrating the blame-

People also have a basic tendency to justify their culture’s social systems (Jost et al., 2009; Kay et al., 2009). We’re inclined to see the way things are as the way they ought to be. This natural conservatism makes it difficult to legislate major social changes, such as health care or climate-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- When prejudiced judgment causes us to blame an undeserving person for a problem, that person is called a ______________.

scapegoat