45.1 Attraction

Pause a moment and think about your relationships with two people—

The Psychology of Attraction

45-

We endlessly wonder how we can win others’ affection and what makes our own affections flourish or fade. Does familiarity breed contempt, or does it amplify affection? Do birds of a feather flock together, or do opposites attract? Is beauty only skin deep, or does physical attractiveness matter greatly? To explore these questions, let’s consider three ingredients of our liking for one another: proximity, attractiveness, and similarity.

ProximityBefore friendships become close, they must begin. Proximity—geographic nearness—

Proximity breeds liking partly because of the mere exposure effect. Repeated exposure to novel stimuli increases our liking for them. This applies to nonsense syllables, musical selections, geometric figures, Chinese characters, human faces, and the letters of our own name (Moreland & Zajonc, 1982; Nuttin, 1987; Zajonc, 2001). We are even somewhat more likely to marry someone whose first or last name resembles our own (Jones et al., 2004).

So, within certain limits, familiarity feeds fondness (Bornstein, 1989, 1999). Researchers demonstrated this by having four equally attractive women silently attend a 200-

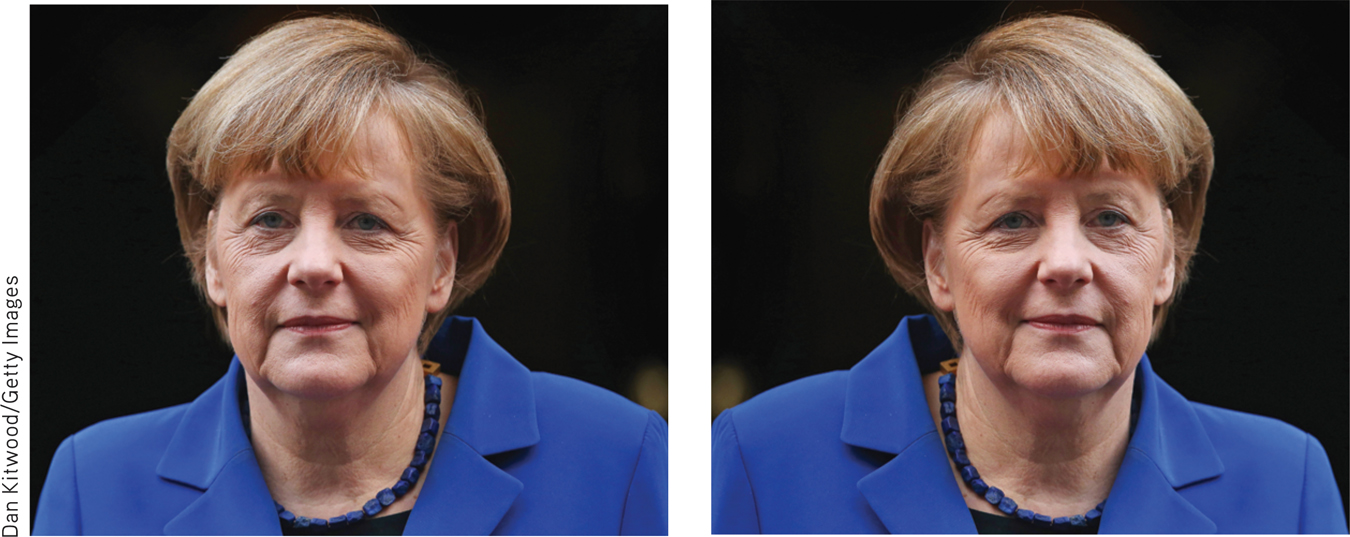

No face is more familiar than your own. And that helps explain an interesting finding by Lisa DeBruine (2004): We like other people when their faces incorporate some morphed features of our own. When DeBruine (2002) had McMaster University students (both men and women) play a game with a supposed other player, they were more trusting and cooperative when the other person’s image had some of their own facial features morphed into it. In me I trust. (See also FIGURE 45.1.)

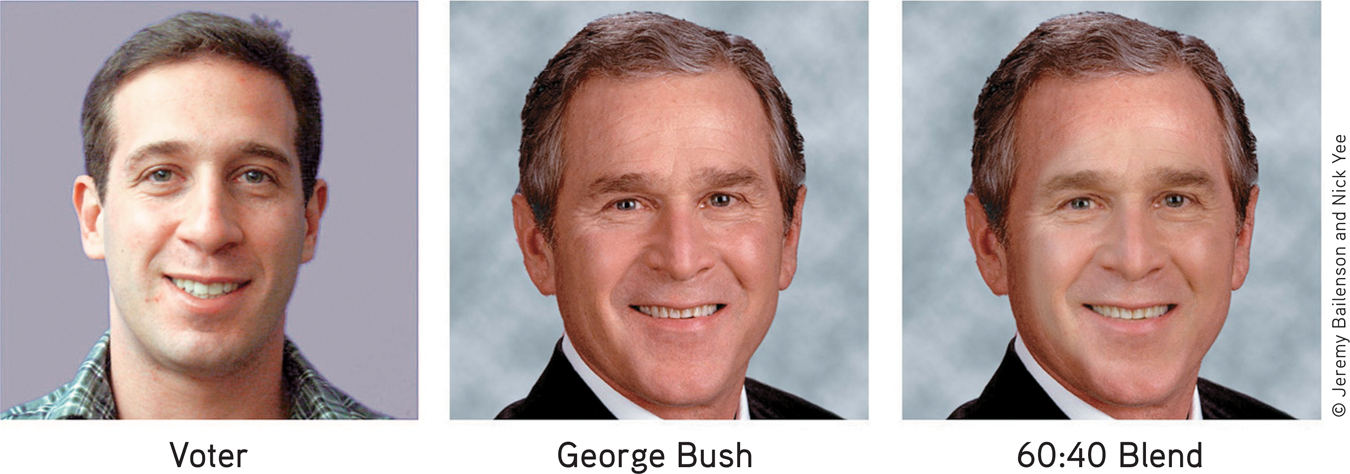

Figure 45.1

Figure 45.1I like the candidate who looks a bit like dear old me Jeremy Bailenson and his colleagues (2005) incorporated morphed features of voters’ faces into the faces of 2004 U.S. presidential candidates George Bush and John Kerry. Without conscious awareness of their own incorporated features, the participants became more likely to favor the candidate whose face incorporated some of their own features.

For our ancestors, the mere exposure effect had survival value. What was familiar was generally safe and approachable. What was unfamiliar was more often dangerous and threatening. Evolution may therefore have hard-

Modern MatchmakingThose who have not found a romantic partner in their immediate proximity may cast a wider net by joining an online dating service. Published research on Internet matchmaking effectiveness is sparse. But this much seems well established: Some people, including occasional predators, dishonestly represent their age, attractiveness, occupation, or other details, and thus are not who they seem to be. Nevertheless, Katelyn McKenna and John Bargh and their colleagues have offered a surprising finding: Compared with relationships formed in person, Internet-

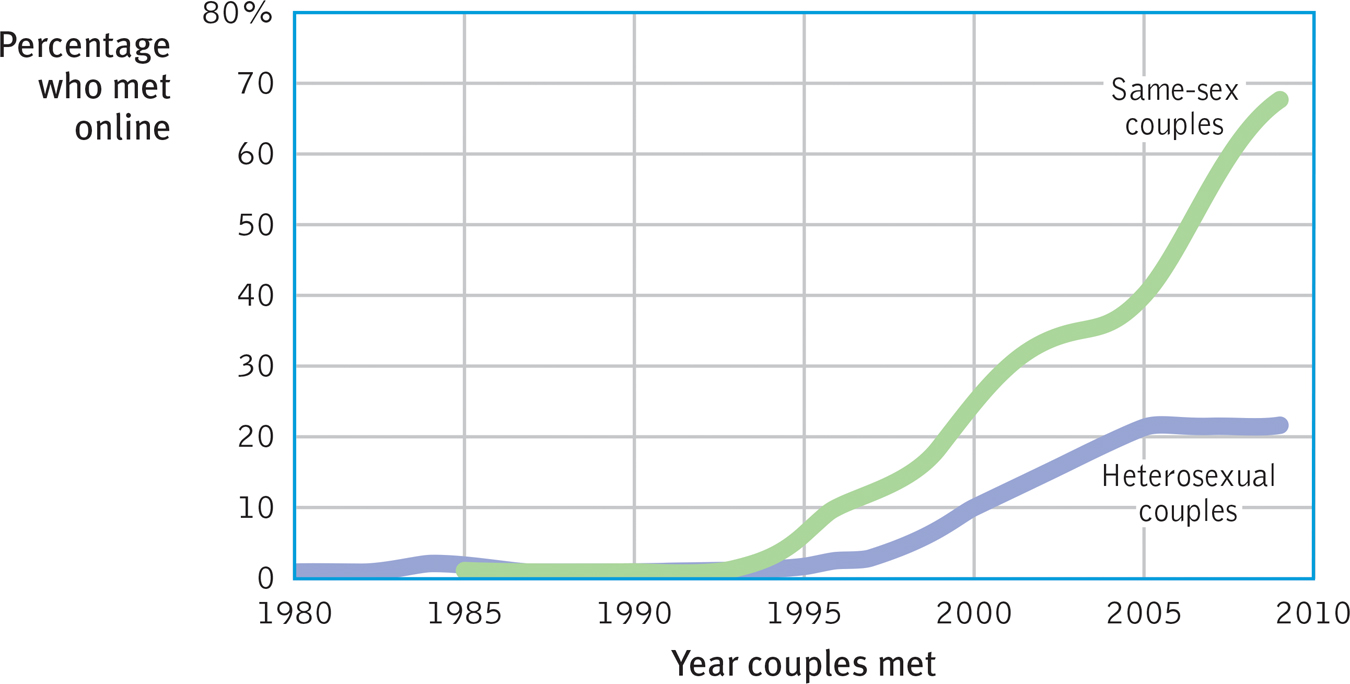

Figure 45.2

Figure 45.2Percent of heterosexual and same-

Speed dating pushes the search for romance into high gear. In a process pioneered by a matchmaking Jewish rabbi, people meet a succession of prospective partners, either in person or via webcam (Bower, 2009). After a 3-

For researchers, speed dating offers a unique opportunity for studying influences on our first impressions of potential romantic partners. Among recent findings are these:

- Men are more transparent. Observers (male or female) watching videos of speed-dating encounters can read a man’s level of romantic interest more accurately than a woman’s (Place et al., 2009).

- Given more options, people’s choices become more superficial. Meeting lots of potential partners leads people to focus on more easily assessed characteristics, such as height and weight (Lenton & Francesconi, 2010). This was true even when researchers controlled for time spent with each partner.

- Men wish for future contact with more of their speed dates; women tend to be more choosy. But this difference disappears if the conventional roles are reversed, so that men stay seated while women circulate (Finkel & Eastwick, 2009).

Physical AttractivenessOnce proximity affords us contact, what most affects our first impressions? The person’s sincerity? Intelligence? Personality? Hundreds of experiments reveal that it is something far more superficial: physical appearance. This finding is unnerving for those of us taught that “beauty is only skin deep” and “appearances can be deceiving.”

In one early study, researchers randomly matched new University of Minnesota students for a Welcome Week dance (Walster et al., 1966). Before the dance, the researchers gave each student a battery of personality and aptitude tests, and they rated each student’s physical attractiveness. During the blind date, the couples danced and talked for more than two hours and then took a brief intermission to rate their dates. What determined whether they liked each other? Only one thing seemed to matter: appearance. Both the men and the women liked good-

Physical attractiveness also predicts how often people date and how popular they feel. It affects initial impressions of people’s personalities. We don’t assume that attractive people are more compassionate, but research participants perceive them as healthier, happier, more sensitive, more successful, and more socially skilled (Eagly et al., 1991; Feingold, 1992; Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986). Attractive, well-

Even babies have preferred attractive over unattractive faces (Langlois et al., 1987). So do some blind people, as University of Birmingham professor John Hull (1990, p. 23) discovered after going blind. A colleague’s remarks on a woman’s beauty would strangely affect his feelings. He found this “deplorable.… What can it matter to me what sighted men think of women … yet I do care what sighted men think, and I do not seem able to throw off this prejudice.”

“Personal beauty is a greater recommendation than any letter of introduction.”

Aristotle, Apothegems, 330 b.c.e.

For those who find the importance of looks unfair and unenlightened, two findings may be reassuring. First, people’s attractiveness is surprisingly unrelated to their self-

Beauty is also in the eye of the culture. Hoping to look attractive, people across the globe have pierced and tattooed their bodies, lengthened their necks, bound their feet, and dyed their hair. They have gorged themselves to achieve a full figure or liposuctioned fat to achieve a slim one, applied chemicals hoping to rid themselves of unwanted hair or to regrow wanted hair, strapped on leather garments to make their breasts seem smaller or surgically filled their breasts with silicone and worn Wonderbras to make them look bigger. Cultural ideals change over time. For women in North America, the ultra-

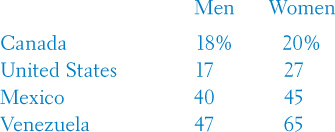

Percentage of Men and Women Who “Constantly Think About Their Looks”

From Roper Starch survey, reported by McCool (1999).

Some aspects of attractiveness, however, do cross place and time (Cunningham et al., 2005; Langlois et al., 2000). By providing reproductive clues, bodies influence sexual attraction. As evolutionary psychologists explain, men in many cultures, from Australia to Zambia, judge women as more attractive if they have a youthful, fertile appearance, suggested by a low waist-

Women have 91 percent of cosmetic procedures (ASPS, 2010). Women also recall others’ appearances better than do men (Mast & Hall, 2006).

Estimated length of human nose removed by U.S. plastic surgeons each year: 5469 feet (Harper’s, 2009).

People everywhere also seem to prefer physical features—

Figure 45.3

Figure 45.3Average is attractive Which of these faces offered by University of St. Andrews psychologist David Perrett (2002, 2010) is most attractive? Most people say it’s the face on the right—

Our feelings also influence our attractiveness judgments. Imagine two people. The first is honest, humorous, and polite. The second is rude, unfair, and abusive. Which one is more attractive? Most people perceive the person with the appealing traits as more physically attractive (Lewandowski et al., 2007). Those we like we find attractive. In a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, Prince Charming asks Cinderella, “Do I love you because you’re beautiful, or are you beautiful because I love you?” Chances are it’s both. As we see our loved ones again and again, their physical imperfections grow less noticeable and their attractiveness grows more apparent (Beaman & Klentz, 1983; Gross & Crofton, 1977). Shakespeare said it in A Midsummer Night’s Dream: “Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind.” Come to love someone and watch beauty grow.

SimilaritySo proximity has brought you into contact with someone, and your appearance has made an acceptable first impression. What influences whether you will become friends? As you get to know each other, will the chemistry be better if you are opposites or if you are alike?

It makes a good story—

Moreover, the more alike people are, the more their liking endures (Byrne, 1971). Journalist Walter Lippmann was right to suppose that love lasts “when the lovers love many things together, and not merely each other.” Similarity breeds content. One app therefore matches people with potential dates based on their proximity, and on the similarity of their Facebook profiles.

Proximity, attractiveness, and similarity are not the only determinants of attraction. We also like those who like us. This is especially true when our self-

Indeed, all the findings we have considered so far can be explained by a simple reward theory of attraction: We will like those whose behavior is rewarding to us, including those who are both able and willing to help us achieve our goals (Montoya & Horton, 2014). When people live or work in close proximity to us, it requires less time and effort to develop the friendship and enjoy its benefits. When people are attractive, they are aesthetically pleasing, and associating with them can be socially rewarding. When people share our views, they reward us by validating our beliefs.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- People tend to marry someone who lives or works nearby. This is an example of the ________ _____________ ___________ in action.

mere exposure effect

- How does being physically attractive influence others’ perceptions?

Being physically attractive tends to elicit positive first impressions. People tend to assume that attractive people are healthier, happier, and more socially skilled than others are.

Romantic Love

45-

Sometimes people move quickly from initial impressions, to friendship, to the more intense, complex, and mysterious state of romantic love. If love endures, temporary passionate love will mellow into a lingering companionate love (Hatfield, 1988).

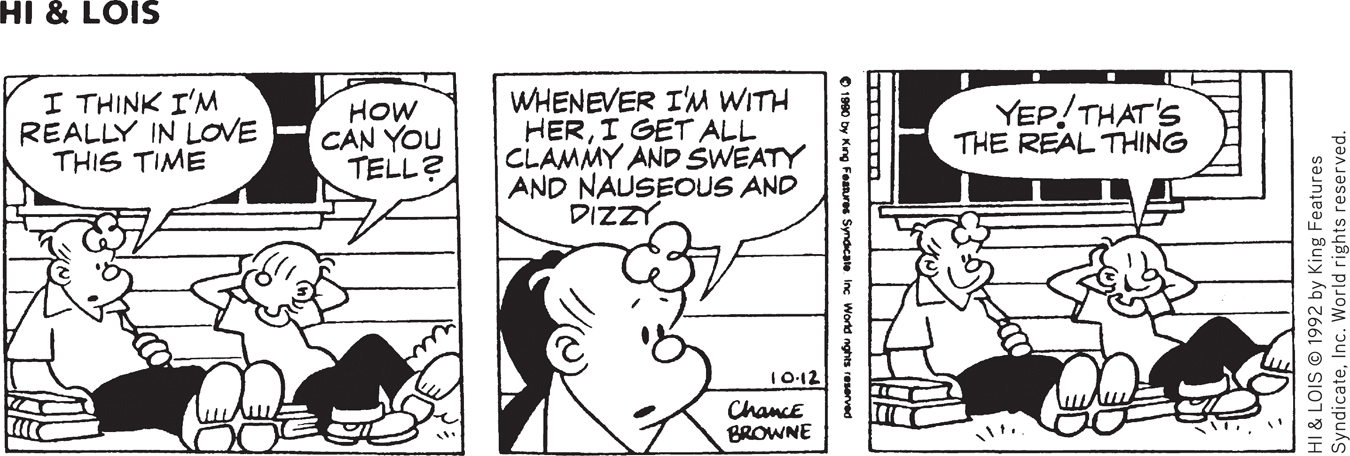

Passionate LoveA key ingredient of passionate love is arousal. The two-

- emotions have two ingredients—physical arousal plus cognitive appraisal.

- arousal from any source can enhance one emotion or another, depending on how we interpret and label the arousal.

Arousal can come from within, as we experience the excitement of a new relationship. But in tests of the two-

A sample experiment: Researchers studied people crossing two bridges above British Columbia’s rocky Capilano River (Dutton & Aron, 1974, 1989). One, a swaying footbridge, was 230 feet above the rocks; the other was low and solid. The researchers had an attractive young woman intercept men coming off each bridge, and ask their help in filling out a short questionnaire. She then offered her phone number in case they wanted to hear more about her project. Far more of those who had just crossed the high bridge—

Companionate LoveAlthough the desire and attachment of romantic love often endure, the intense absorption in the other, the thrill of the romance, the giddy “floating on a cloud” feelings typically fade. Does this mean the French are correct in saying that “love makes the time pass and time makes love pass”? Or can friendship and commitment keep a relationship going after the passion cools?

As love matures, it typically becomes a steadier companionate love—a deep, affectionate attachment (Hatfield, 1988). The flood of passion-

There may be adaptive wisdom to the shift from passion to attachment (Reis & Aron, 2008). Passionate love often produces children, whose survival is aided by the parents’ waning obsession with each other. Failure to appreciate passionate love’s limited half-

“When two people are under the influence of the most violent, most insane, most delusive, and most transient of passions, they are required to swear that they will remain in that excited, abnormal, and exhausting condition continuously until death do them part.”

George Bernard Shaw, “Getting Married,” 1908

One key to a gratifying and enduring relationship is equity. When equity exists—

Equity’s importance extends beyond marriage. Mutually sharing one’s self and possessions, making decisions together, giving and getting emotional support, promoting and caring about each other’s welfare—

Another vital ingredient of loving relationships is self-disclosure, the revealing of intimate details about ourselves—

One experiment marched student pairs through 45 minutes of increasingly self-

Intimacy can also grow when we pause to ponder and write our feelings. Researchers invited one person from each of 86 dating couples to spend 20 minutes a day over three days either writing their deepest thoughts and feelings about the relationship or writing merely about their daily activities (Slatcher & Pennebaker, 2006). Those who wrote about their feelings expressed more emotion in their instant messages with their partners in the days following, and 77 percent were still dating three months later (compared with 52 percent of those who had written about their activities).

In addition to equity and self-

In the mathematics of love, self-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How does the two-factor theory of emotion help explain passionate love?

Emotions consist of (1) physical arousal and (2) our interpretation of that arousal. Researchers have found that any source of arousal (running, fear, laughter) may be interpreted as passion in the presence of a desirable person.

- Two vital components for maintaining companionate love are __________ and ___________ - __________.

equity; self-