45.2 Altruism

45-

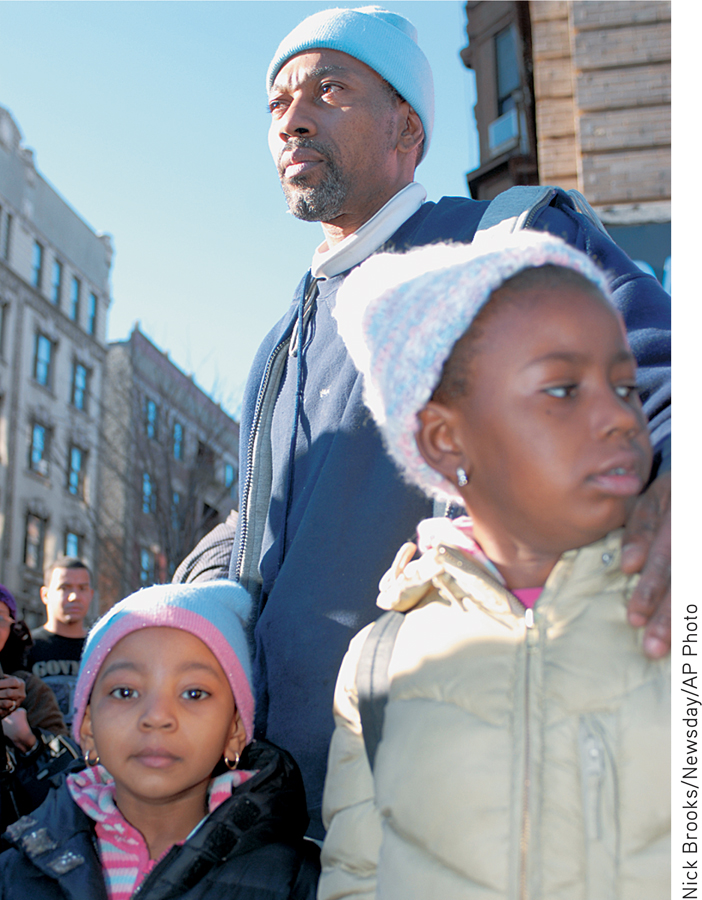

Altruism is an unselfish concern for the welfare of others. In rescuing his jailer, Dirk Willems exemplified altruism. So also did Carl Wilkens and Paul Rusesabagina in Kigali, Rwanda. Wilkens, a Seventh Day Adventist missionary, was living there in 1994 with his family when militia from the Hutu ethnic group began to slaughter members of a minority ethnic group, the Tutsis. The U.S. government, church leaders, and friends all implored Wilkens to leave. He refused. After evacuating his family, and even after every other American had left Kigali, he alone stayed and contested the 800,000-

Elsewhere in Kigali, Rusesabagina, a Hutu married to a Tutsi and the acting manager of a luxury hotel, was sheltering more than 1200 terrified Tutsis and moderate Hutus. When international peacekeepers abandoned the city and hostile militia threatened his guests in the “Hotel Rwanda” (as it came to be called in a 2004 movie), the courageous Rusesabagina began cashing in past favors. He bribed the militia and telephoned influential people abroad to exert pressure on local authorities, thereby sparing the lives of the hotel’s occupants from the surrounding chaos. Both Wilkens and Rusesabagina were displaying altruism, an unselfish regard for the welfare of others.

Altruism became a major concern of social psychologists after an especially vile act. On March 13, 1964, a stalker repeatedly stabbed Kitty Genovese, then raped her as she lay dying outside her Queens, New York, apartment at 3:30 a.m. “Oh, my God, he stabbed me!” Genovese screamed into the early morning stillness. “Please help me!” Windows opened and lights went on as neighbors heard her screams. Her attacker fled and then returned to stab and rape her again. Not until he had fled for good did anyone so much as call the police, at 3:50 a.m.

Bystander Intervention

Reflecting on initial reports of the Genovese murder and other such tragedies, most commentators were outraged by the bystanders’ apparent “apathy” and “indifference.” Rather than blaming the onlookers, social psychologists John Darley and Bibb Latané (1968b) attributed their inaction to an important situational factor—

“Probably no single incident has caused social psychologists to pay as much attention to an aspect of social behavior as Kitty Genovese’s murder.”

R. Lance Shotland (1984)

After staging emergencies under various conditions, Darley and Latané assembled their findings into a decision scheme: We will help only if the situation enables us first to notice the incident, then to interpret it as an emergency, and finally to assume responsibility for helping (FIGURE 45.4). At each step, the presence of others can turn us away from the path that leads to helping.

Figure 45.4

Figure 45.4The decision-

Darley and Latané reached their conclusions after interpreting the results of a series of experiments. For example, as students in different laboratory rooms talked over an intercom, the experimenters simulated an emergency. Each student was in a separate cubicle, and only the person whose microphone was switched on could be heard. When his turn came, one student (an accomplice of the experimenters) made sounds as though he were having an epileptic seizure, and he called for help (Darley & Latané, 1968a).

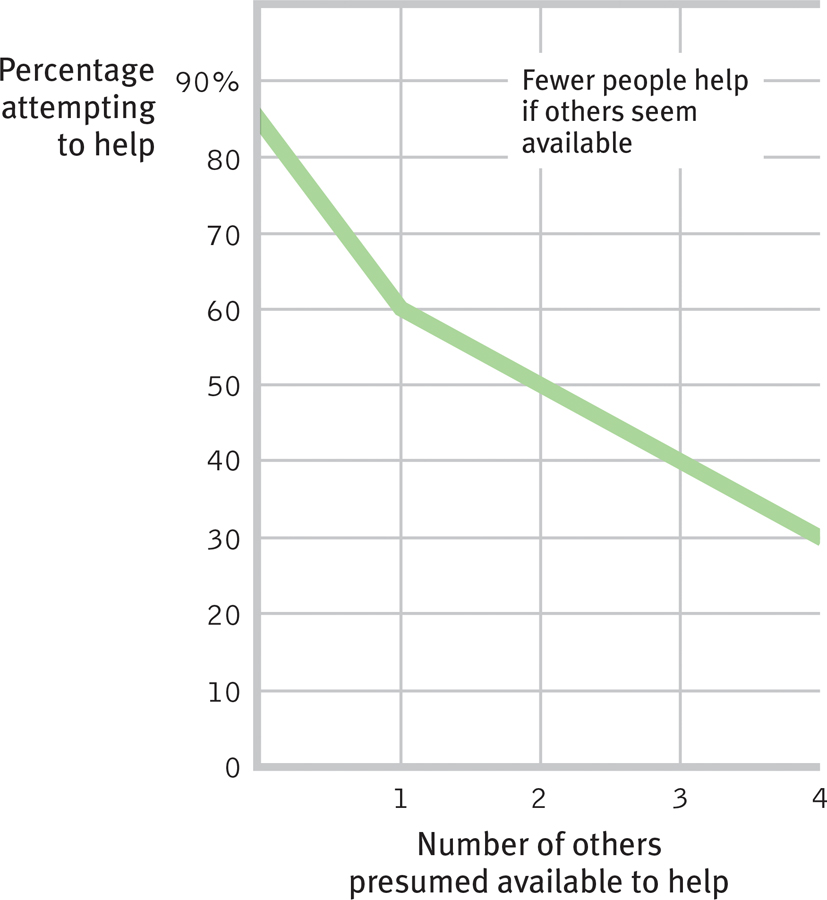

How did the others react? As FIGURE 45.5 shows, those who believed only they could hear the victim—

Figure 45.5

Figure 45.5Responses to a simulated physical emergency When people thought they alone heard the calls for help from a person they believed to be having an epileptic seizure, they usually helped. But when they thought four others were also hearing the calls, fewer than a third responded. (Data from Darley & Latané, 1968a.)

For a review of research on emergency helping, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: When Will People Help Others?

For a review of research on emergency helping, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: When Will People Help Others?

Hundreds of additional experiments have confirmed this bystander effect. For example, researchers and their assistants took 1497 elevator rides in three cities and “accidentally” dropped coins or pencils in front of 4813 fellow passengers (Latané & Dabbs, 1975). When alone with the person in need, 40 percent helped; in the presence of 5 other bystanders, only 20 percent helped.

Observations of behavior in thousands of these situations—

- the person appears to need and deserve help.

- the person is in some way similar to us.

- the person is a woman.

- we have just observed someone else being helpful.

- we are not in a hurry.

- we are in a small town or rural area.

- we are feeling guilty.

- we are focused on others and not preoccupied.

- we are in a good mood.

This last result, that happy people are helpful people, is one of the most consistent findings in all of psychology. As poet Robert Browning (1868) observed, “Oh, make us happy and you make us good!” It doesn’t matter how we are cheered. Whether by being made to feel successful and intelligent, by thinking happy thoughts, by finding money, or even by receiving a posthypnotic suggestion, we become more generous and more eager to help (Carlson et al., 1988). And given a feeling of elevation after witnessing or learning of someone else’s self-

So happiness breeds helpfulness. But it’s also true that helpfulness breeds happiness. Making charitable donations activates brain areas associated with reward (Harbaugh et al., 2007). That helps explain a curious finding: People who give money away are happier than those who spend it almost entirely on themselves. In a survey of more than 200,000 people worldwide, people in both rich and poor countries were happier with their lives if they had donated to a charity in the last month (Aknin et al., 2013). Just reflecting on a time when one spent money on others provides most people with a mood boost. And in one experiment, researchers gave people an envelope with cash and instructions either to spend it on themselves or to spend it on others (Dunn et al., 2008, 2013). Which group was happiest at the day’s end? It was, indeed, those assigned to the spend-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Why didn’t anybody help Kitty Genovese? What social psychology principle did this incident illustrate?

In the presence of others, an individual is less likely to notice a situation, correctly interpret it as an emergency, and take responsibility for offering help. The Kitty Genovese case demonstrated this bystander effect, as each witness assumed many others were also aware of the event.

The Norms for Helping

45-

Why do we help? One widely held view is that self-

Others believe that we help because we have been socialized to do so, through norms that prescribe how we ought to behave. Through socialization, we learn the reciprocity norm: the expectation that we should return help, not harm, to those who have helped us. In our relations with others of similar status, the reciprocity norm compels us to give (in favors, gifts, or social invitations) about as much as we receive. In one experiment, people who were generously treated also became more likely to be generous to a stranger—

The reciprocity norm kicked in after Dave Tally, a Tempe, Arizona homeless man, found $3300 in a backpack that an Arizona State University student had misplaced on his way to buy a used car (Lacey, 2010). Instead of using the cash for much-

We also learn a social-responsibility norm: that we should help those who need our help—

People who attend weekly religious services often are admonished to practice the social-