46.2 Psychodynamic Theories

Psychodynamic theories of personality view human behavior as a dynamic interaction between the conscious mind and the unconscious mind, including associated motives and conflicts. These theories are descended from Freud’s psychoanalysis—his theory of personality and the associated treatment techniques. Freud was the first to focus clinical attention on our unconscious mind.

Freud’s Psychoanalytic Perspective: Exploring the Unconscious

46-

Ask 100 people on the street to name a notable deceased psychologist, suggested Keith Stanovich (1996, p. 1), and “Freud would be the winner hands down.” In the popular mind, he is to psychology what Elvis Presley is to rock music. Freud’s influence not only lingers in psychiatry and clinical psychology, but also in literary and film interpretation. Almost 9 in 10 American college courses that reference psychoanalysis have been outside of psychology departments (Cohen, 2007). His early twentieth-

Like all of us, Sigmund Freud was a product of his times. His Victorian era was a time of tremendous discovery and scientific advancement, but it is also known today as a time of sexual repression and male dominance. Men’s and women’s roles were clearly defined, with male superiority assumed and only male sexuality generally acknowledged (discreetly).

“The female … acknowledges the fact of her castration, and with it, too, the superiority of the male and her own inferiority; but she rebels against this unwelcome state of affairs.”

Sigmund Freud, Female Sexuality, 1931

Long before entering the University of Vienna in 1873, young Freud showed signs of independence and brilliance. He so loved reading plays, poetry, and philosophy that he once ran up a bookstore debt beyond his means. As a teen he often took his evening meal in his tiny bedroom in order to lose no time from his studies. After medical school he set up a private practice specializing in nervous disorders. Before long, however, he faced patients whose disorders made no neurological sense. A patient might have lost all feeling in a hand—

Might some neurological disorders have psychological causes? Observing patients led Freud to his “discovery” of the unconscious. He speculated that lost feeling in one’s hand might be caused by a fear of touching one’s genitals; that unexplained blindness or deafness might be caused by not wanting to see or hear something that aroused intense anxiety. After some early unsuccessful trials with hypnosis, Freud turned to free association, in which he told the patient to relax and say whatever came to mind, no matter how embarrassing or trivial. He assumed that a line of mental dominoes had fallen from his patients’ distant past to their troubled present. Free association, he believed, would allow him to retrace that line, following a chain of thought leading into the patient’s unconscious. There, painful unconscious memories, often from childhood, could be retrieved and released.

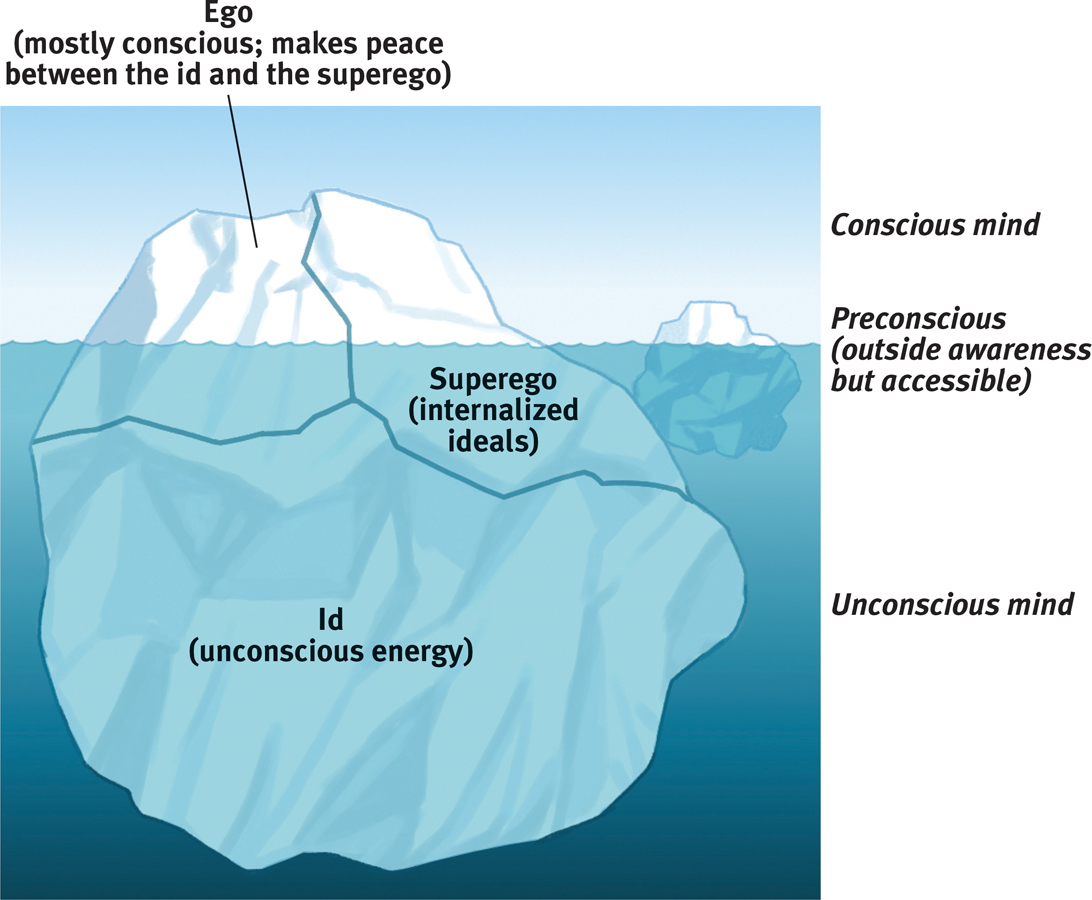

Basic to Freud’s theory was his belief that the mind is mostly hidden (FIGURE 46.1). Our conscious awareness is like the part of an iceberg that floats above the surface. Beneath our awareness is the larger unconscious mind, with its thoughts, wishes, feelings, and memories. Some of these thoughts we store temporarily in a preconscious area, from which we can retrieve them into conscious awareness. Of greater interest to Freud was the mass of unacceptable passions and thoughts that he believed we repress, or forcibly block from our consciousness because they would be too unsettling to acknowledge. Freud believed that without our awareness, these troublesome feelings and ideas powerfully influence us, sometimes gaining expression in disguised forms—

Figure 46.1

Figure 46.1Freud’s idea of the mind’s structure Psychologists have used an iceberg image to illustrate Freud’s idea that the mind is mostly hidden beneath the conscious surface. Note that the id is totally unconscious, but ego and superego operate both consciously and unconsciously. Unlike the parts of a frozen iceberg, however, the id, ego, and superego interact.

Personality Structure

46-

In Freud’s view, human personality—

The id’s unconscious psychic energy constantly strives to satisfy basic drives to survive, reproduce, and aggress. The id operates on the pleasure principle: It seeks immediate gratification. To envision an id-

As the ego develops, the young child responds to the real world. The ego, operating on the reality principle, seeks to gratify the id’s impulses in realistic ways that will bring long-

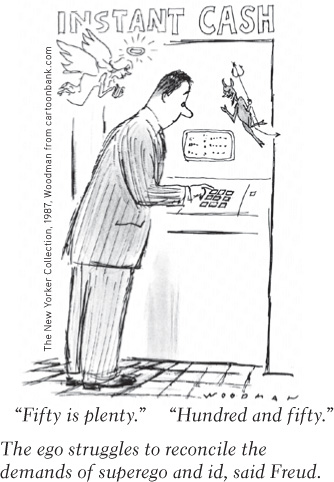

Around age 4 or 5, Freud theorized, a child’s ego recognizes the demands of the newly emerging superego, the voice of our moral compass (conscience) that forces the ego to consider not only the real but the ideal. The superego focuses on how we ought to behave. It strives for perfection, judging actions and producing positive feelings of pride or negative feelings of guilt. Someone with an exceptionally strong superego may be virtuous yet guilt ridden; another with a weak superego may be outrageously self-

Because the superego’s demands often oppose the id’s, the ego struggles to reconcile the two. It is the personality “executive,” mediating among the impulsive demands of the id, the restraining demands of the superego, and the real-

Personality Development

46-

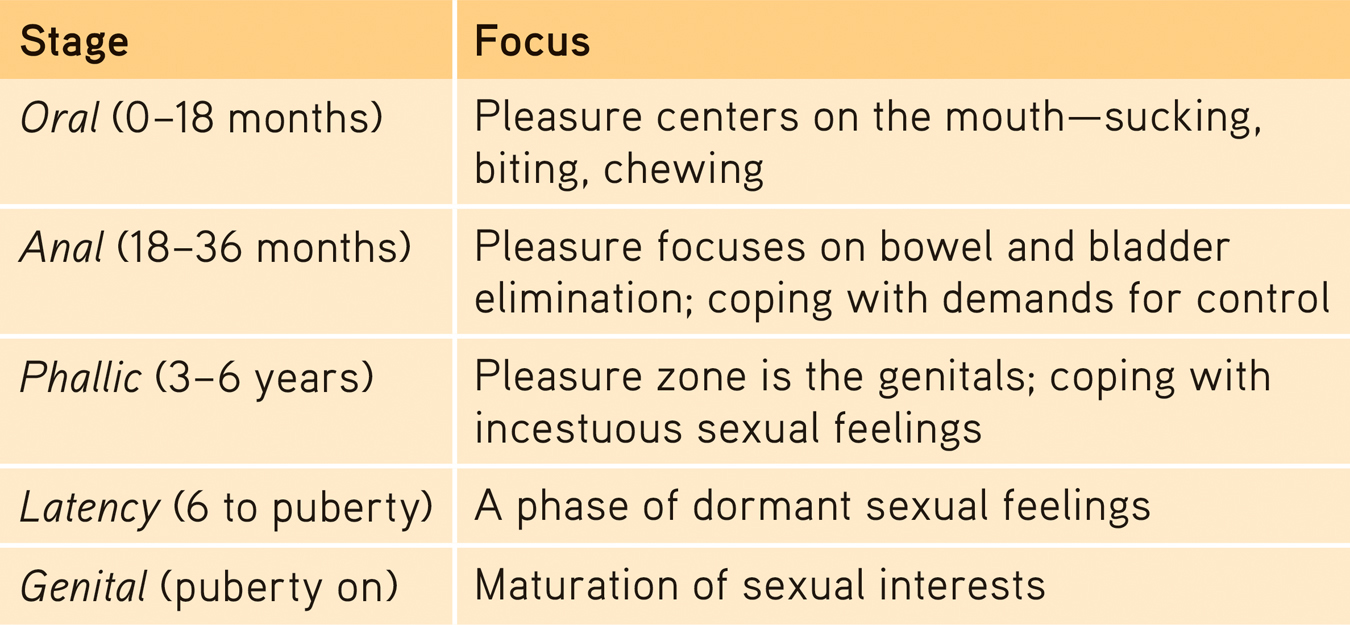

Analysis of his patients’ histories convinced Freud that personality forms during life’s first few years. He concluded that children pass through a series of psychosexual stages, during which the id’s pleasure-

Table 46.1

Table 46.1Freud’s Psychosexual Stages

Freud believed that during the phallic stage, for example, boys seek genital stimulation. They also develop both unconscious sexual desires for their mother and jealousy and hatred for their father, whom they consider a rival. Given these feelings, he thought, boys also experience guilt and a lurking fear of punishment, perhaps by castration, from their father. Freud called this collection of feelings the Oedipus complex after the Greek legend of Oedipus, who unknowingly killed his father and married his mother. Some psychoanalysts in Freud’s era believed that girls experienced a parallel Electra complex.

Children eventually cope with the threatening feelings, said Freud, by repressing them and by identifying with (trying to become like) the rival parent. It’s as though something inside the child decides, “If you can’t beat ‘em [the same-

In Freud’s view, conflicts unresolved during earlier psychosexual stages could surface as maladaptive behavior in the adult years. At any point in the oral, anal, or phallic stages, strong conflict could lock, or fixate, the person’s pleasure-

Freud’s ideas of sexuality were controversial in his own time. “Freud was called a dirty-

Defense Mechanisms

46-

Anxiety, said Freud, is the price we pay for civilization. As members of social groups, we must control our sexual and aggressive impulses, not act them out. But sometimes the ego fears losing control of this inner id-

“I remember your name perfectly but I just can’t think of your face.”

Oxford professor W. A. Spooner (1844– 1930) famous for his linguistic flip-flops (spoonerisms). Spooner rebuked one student for “fighting a liar in the quadrangle” and another who “hissed my mystery lecture,” adding “You have tasted two worms.”

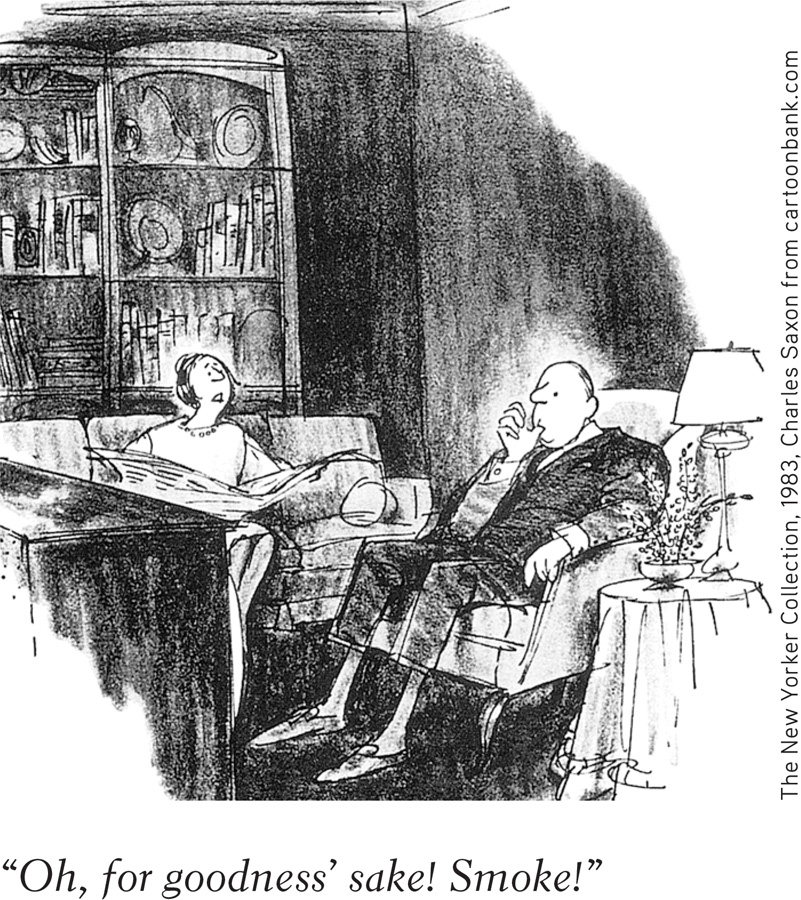

Freud proposed that the ego protects itself with defense mechanisms—tactics that reduce or redirect anxiety by distorting reality. For Freud, all defense mechanisms function indirectly and unconsciously. Just as the body unconsciously defends itself against disease, so also does the ego unconsciously defend itself against anxiety. For example, repression banishes anxiety-

Freud believed he could glimpse the unconscious seeping through when a financially stressed patient, not wanting any large pills, said, “Please do not give me any bills, because I cannot swallow them.” (Similarly, sex-

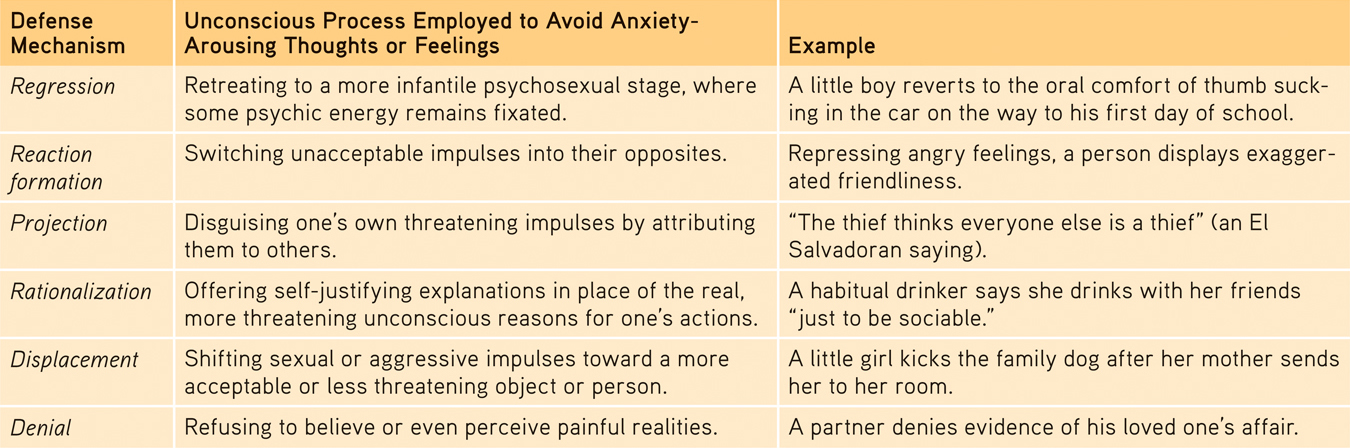

TABLE 46.2 describes a sampling of six other well-

Table 46.2

Table 46.2Six Defense Mechanisms

Freud believed that repression, the basic mechanism that banishes anxiety-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- According to Freud’s ideas about the three-part personality structure, the ____________operates on the reality principle and tries to balance demands in a way that produces long-term pleasure rather than pain; the____________operates on the pleasure principle and seeks immediate gratification; and the____________represents the voice of our internalized ideals (our conscience).

ego; id; superego

- In the psychoanalytic view, conflicts unresolved during one of the psychosexual stages may lead to____________at that stage.

fixation

- Freud believed that our defense mechanisms operate____________(consciously/ unconsciously) and defend us against____________.

unconsciously; anxiety

The Neo-Freudian and Later Psychodynamic Theorists

46-

In a historical period when people never talked about sex, and certainly not unconscious desires for sex with one’s parent, Freud’s writings prompted considerable debate. “In the Middle Ages, they would have burned me,” observed Freud to a friend. “Now they are content with burning my books” (Jones, 1957). Despite the controversy, Freud attracted followers. Several young, ambitious physicians formed an inner circle around their strong-

Alfred Adler and Karen Horney [HORN-

Alfred Adler “The individual feels at home in life and feels his existence to be worthwhile just so far as he is useful to others and is overcoming feelings of inferiority” (Problems of Neurosis, 1964).

|

Karen Horney “The view that women are infantile and emotional creatures, and as such, incapable of responsibility and independence is the work of the masculine tendency to lower women’s self-

|

Carl Jung “From the living fountain of instinct flows everything that is creative; hence the unconscious is the very source of the creative impulse” (The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche, 1960).

|

Carl Jung started out a strong follower of Freud, but then he veered off on his own. Jung placed less emphasis on social factors and agreed with Freud that the unconscious exerts a powerful influence. But to Jung [Yoong], the unconscious contains more than our repressed thoughts and feelings. He believed we also have a collective unconscious, a common reservoir of images, or archetypes, derived from our species’ universal experiences. Jung said that the collective unconscious explains why, for many people, spiritual concerns are deeply rooted and why people in different cultures share certain myths and images. Most of today’s psychodynamic psychologists and other psychological theorists discount the idea of inherited experiences, but do believe that our shared evolutionary history shaped some universal dispositions. They are also aware that experience can leave epigenetic marks.

Freud died in 1939. Since then, some of his ideas have been incorporated into the diversity of perspectives that make up psychodynamic theory. “Most contemporary [psychodynamic] theorists and therapists are not wedded to the idea that sex is the basis of personality,” noted Drew Westen (1996). They “do not talk about ids and egos, and do not go around classifying their patients as oral, anal, or phallic characters.” What they do assume, with Freud and with much support from today’s psychological science, is that much of our mental life is unconscious. With Freud, they also assume that we often struggle with inner conflicts among our wishes, fears, and values, and that childhood shapes our personality and ways of becoming attached to others.

For a helpful, 9-minute overview, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Psychodynamic Theories of Personality.

For a helpful, 9-minute overview, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Psychodynamic Theories of Personality.

Assessing Unconscious Processes

46-

Personality tests reflect the basic ideas of particular personality theories. Such tools, useful to those who study personality or provide therapy, are tailored to test specific theories. So, what might be the assessment tool of choice for someone working in the Freudian tradition?

Such a test would need to provide some sort of road into the unconscious, to unearth the residue of early childhood experiences, to move beneath surface pretensions and reveal hidden conflicts and impulses. Objective assessment tools, such as agree-

Projective tests aim to provide this “psychological X-

Henry Murray (1933) demonstrated a possible basis for such a test at a party hosted by his 11-

A few years later, Murray introduced the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT)—a test in which people view ambiguous pictures and then make up stories about them. One use of such storytelling has been to assess achievement motivation (Schultheiss et al., 2014). Shown a daydreaming boy, those who imagine he is fantasizing about an achievement are presumed to be projecting their own goals. “As a rule,” said Murray, “the subject leaves the test happily unaware that he has presented the psychologist with what amounts to an x-

“We don’t see things as they are; we see things as we are.”

The Talmud

The most widely used projective test left some blots on the name of Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach [ROAR-

Figure 46.2

Figure 46.2The Rorschach test In this projective test, people tell what they see in a series of symmetrical inkblots. Some who use this test are confident that the interpretation of ambiguous stimuli will reveal unconscious aspects of the test-

Some clinicians cherish the Rorschach, even offering to judges Rorschach-

“The Rorschach [Inkblot Test] has the dubious distinction of being, simultaneously, the most cherished and the most reviled of all psychological assessment tools.”

John Hunsley and J. Michael Bailey, 1999

But the evidence is insufficient to its revilers, who insist the Rorschach is no emotional MRI. They argue that only a few of the many Rorschach-

Evaluating Freud’s Psychoanalytic Perspective and Modern Views of the Unconscious

46-

Modern Research Contradicts Many of Freud's IdeasWe critique Freud from a twenty-

“Many aspects of Freudian theory are indeed out of date, and they should be: Freud died in 1939, and he has been slow to undertake further revisions.”

Psychologist Drew Westen (1998)

But both Freud’s devotees and detractors agree that recent research contradicts many of his specific ideas. Today’s developmental psychologists see our development as lifelong, not fixed in childhood. They doubt that infants’ neural networks are mature enough to sustain as much emotional trauma as Freud assumed. Some think Freud overestimated parental influence and underestimated peer influence. They also doubt that conscience and gender identity form as the child resolves the Oedipus complex at age 5 or 6. We gain our gender identity earlier, and those who become strongly masculine or feminine do so even without a same-

New psychological research about why we dream disputes Freud’s belief that dreams disguise and fulfill wishes. And slips of the tongue can be explained as competition between similar verbal choices in our memory network. Someone who says “I don’t want to do that—

Psychologists also criticize Freud’s theory for its scientific shortcomings. It’s important to remember that good scientific theories explain observations and offer testable hypotheses. Freud’s theory rests on few objective observations, and parts of it offer few testable hypotheses. For Freud, his own recollections and interpretations of patients’ free associations, dreams, and slips were evidence enough.

What is the most serious problem with Freud’s theory? It offers after-

“We are arguing like a man who should say, ‘If there were an invisible cat in that chair, the chair would look empty; but the chair does look empty; therefore there is an invisible cat in it’.”

C. S. Lewis, Four Loves, 1958

So, should psychology post an “Allow Natural Death” order on this old theory? Freud’s supporters object. To criticize Freudian theory for not making testable predictions is, they say, like criticizing baseball for not being an aerobic exercise, something it was never intended to be. Freud never claimed that psychoanalysis was predictive science. He merely claimed that, looking back, psychoanalysts could find meaning in our state of mind (Rieff, 1979).

“Although [Freud] clearly made a number of mistakes in the formulation of his ideas, his understanding of unconscious mental processes was pretty much on target. In fact, it is very consistent with modern neuroscientists’ belief that most mental processes are unconscious.”

Nobel Prize–winning neuroscientist Eric Kandel (2012)

Freud’s supporters also note that some of his ideas are enduring. It was Freud who drew our attention to the unconscious and the irrational, at a time when such ideas were not popular. Today many researchers study our irrationality (Ariely, 2010). Psychologist Daniel Kahneman won the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics for his studies of our faulty decision making. Freud also drew our attention to the importance of human sexuality, and to the tension between our biological impulses and our social well-

Modern Research Challenges the Idea of RepressionPsychoanalytic theory presumes that we often repress offending wishes, banishing them into the unconscious until they resurface, like long-

“The overall findings … seriously challenge the classical psychoanalytic notion of repression.”

Psychologist Yacov Rofé, “Does Repression Exist?” 2008

Today’s researchers agree that we sometimes spare our egos by neglecting threatening information (Green et al., 2008). Yet many contend that repression, if it ever occurs, is a rare mental response to terrible trauma. Even those who witnessed a parent’s murder or survived Nazi death camps have retained their unrepressed memories of the horror (Helmreich, 1992, 1994; Malmquist, 1986; Pennebaker, 1990). “Dozens of formal studies have yielded not a single convincing case of repression in the entire literature on trauma,” concluded personality researcher John Kihlstrom (2006).

“During the Holocaust, many children … were forced to endure the unendurable. For those who continue to suffer [the] pain is still present, many years later, as real as it was on the day it occurred.”

Eric Zillmer, Molly Harrower, Barry Ritzler, and Robert Archer, The Quest for the Nazi Personality, 1995

Some researchers do believe that extreme, prolonged stress, such as the stress some severely abused children experience, might disrupt memory by damaging the hippocampus (Schacter, 1996). But the far more common reality is that high stress and associated stress hormones enhance memory. Indeed, rape, torture, and other traumatic events haunt survivors, who experience unwanted flashbacks. They are seared onto the soul. “You see the babies,” said Holocaust survivor Sally H. (1979). “You see the screaming mothers. You see hanging people. You sit and you see that face there. It’s something you don’t forget.”

The Modern Unconscious Mind

46-

Freud was right about a big idea that underlies today’s psychodynamic thinking: We indeed have limited access to all that goes on in our minds (Erdelyi, 1985, 1988, 2006; Norman, 2010). Our two-

Nevertheless, many research psychologists now think of the unconscious not as seething passions and repressive censoring but as cooler information processing that occurs without our awareness. To these researchers, the unconscious also involves

- the schemas that automatically control our perceptions and interpretations.

- the priming by stimuli to which we have not consciously attended.

- the right-hemisphere activity that enables the split-brain patient’s left hand to carry out an instruction the patient cannot verbalize.

- the implicit memories that operate without conscious recall, even among those with amnesia.

- the emotions that activate instantly, before conscious analysis.

- the stereotypes that automatically and unconsciously influence how we process information about others.

More than we realize, we fly on autopilot. Our mind wanders, activating the brain’s “default network” (Mason et al., 2007). Unconscious processing occurs constantly. Like an enormous ocean, the unconscious mind is huge. This understanding of unconscious information processing is more like the pre-

There is also research support for two of Freud’s defense mechanisms. For example, one study demonstrated reaction formation (trading unacceptable impulses for their opposite). Men who reported strong anti-

Freud‘s projection (attributing our own threatening impulses to others) has also been confirmed. People do tend to see their traits, attitudes, and goals in others (Baumeister et al., 1998; Maner et al., 2005). Today’s researchers call this the false consensus effect—the tendency to overestimate the extent to which others share our beliefs and behaviors. People who binge-

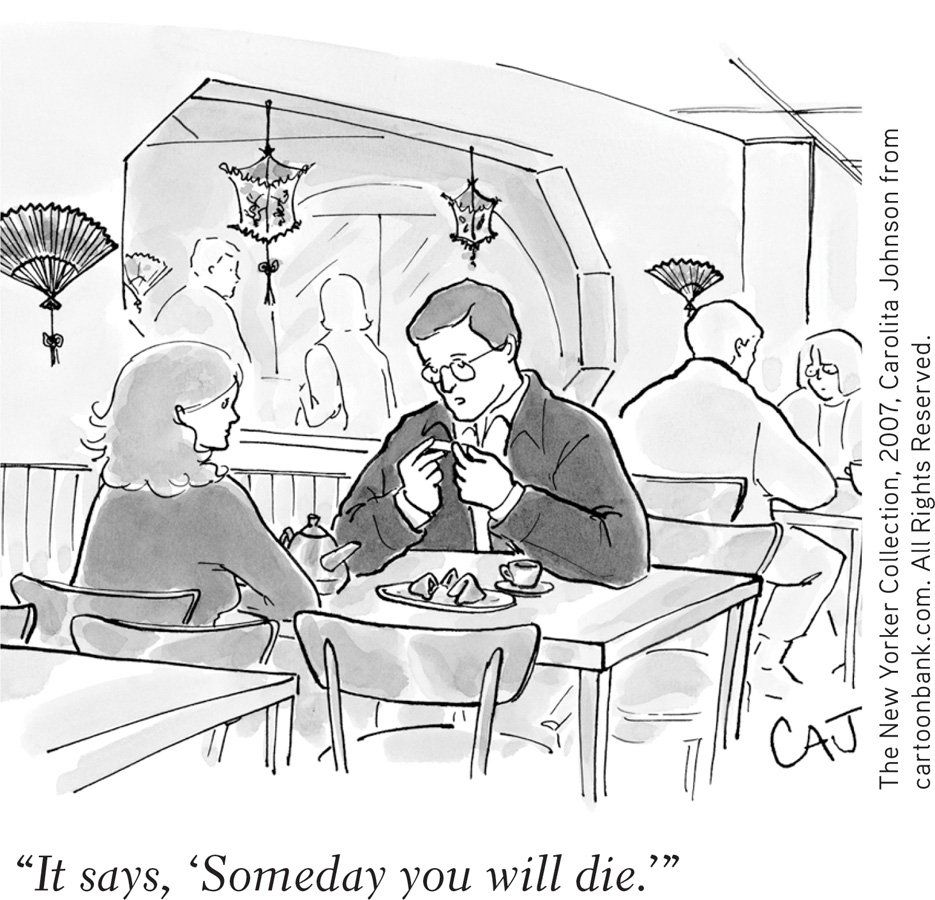

Finally, research has supported Freud’s idea that we unconsciously defend ourselves against anxiety. Researchers have proposed that one source of anxiety is “the terror resulting from our awareness of vulnerability and death” (Greenberg et al., 1997). Nearly 300 experiments testing terror-management theory show that thinking about one’s mortality—

“I sought the Lord, and he answered me and delivered me out of all my terror.”

Psalm 34:4

Faced with a threatening world, people act not only to enhance their self-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What are three big ideas that have survived from Freud’s work in psychoanalytic theory? What are three ways in which Freud’s work has been criticized?

Freud first drew attention to (1) the importance of childhood experiences, (2) the existence of the unconscious mind, and (3) our self-

- Which elements of traditional psychoanalysis have modern-day psychodynamic theorists and therapists retained, and which elements have they mostly left behind?

Today’s psychodynamic theorists and therapists still rely on the interviewing techniques that Freud used, and they still tend to focus on childhood experiences and attachments, unresolved conflicts, and unconscious influences. However, they are not likely to dwell on fixation at any psychosexual stage, or the idea that resolution of sexual issues is the basis of our personality.