47.2 Trait Theories

47-

Rather than focusing on thwarted growth opportunities, unconditional positive regard, and the self-

Like Allport, Isabel Briggs Myers (1987) and her mother, Katharine Briggs, wanted to describe important personality differences. They attempted to sort people according to Carl Jung’s personality types, based on their responses to 126 questions. The Myers-

Most people agree with their announced type profile, which mirrors their declared preferences. They may also accept their label as a basis for being matched with work partners and tasks that supposedly suit their temperaments. But growing research suggests that people should not blindly accept the validity of their test results. A National Research Council report noted that despite the test’s popularity in business and career counseling, its initial use outran research on its value as a predictor of job performance, and “the popularity of this instrument in the absence of proven scientific worth is troublesome” (Druckman & Bjork, 1991, p. 101; see also Pittenger, 1993). Although research on the MBTI has been accumulating since those cautionary words were expressed, the test remains mostly a counseling and coaching tool, not a research instrument.

Exploring Traits

Classifying people as one or another distinct personality type fails to capture their full individuality. We are each a unique complex of multiple traits. So how else could we describe our personalities? We might describe an apple by placing it along several trait dimensions—

What trait dimensions describe personality? If you had an upcoming blind date, what personality traits might give you an accurate sense of the person? Allport and his associate H. S. Odbert (1936) counted all the words in an unabridged dictionary with which one could describe people. There were almost 18,000! How, then, could psychologists condense the list to a manageable number of basic traits?

Factor AnalysisOne technique is factor analysis, a statistical procedure that has also been used to identify clusters (factors) of test items that tap basic components of intelligence (such as spatial ability or verbal skill). Imagine that people who describe themselves as outgoing also tend to say that they like excitement and practical jokes and dislike quiet reading. Such a statistically correlated cluster of behaviors reflects a basic factor, or trait—

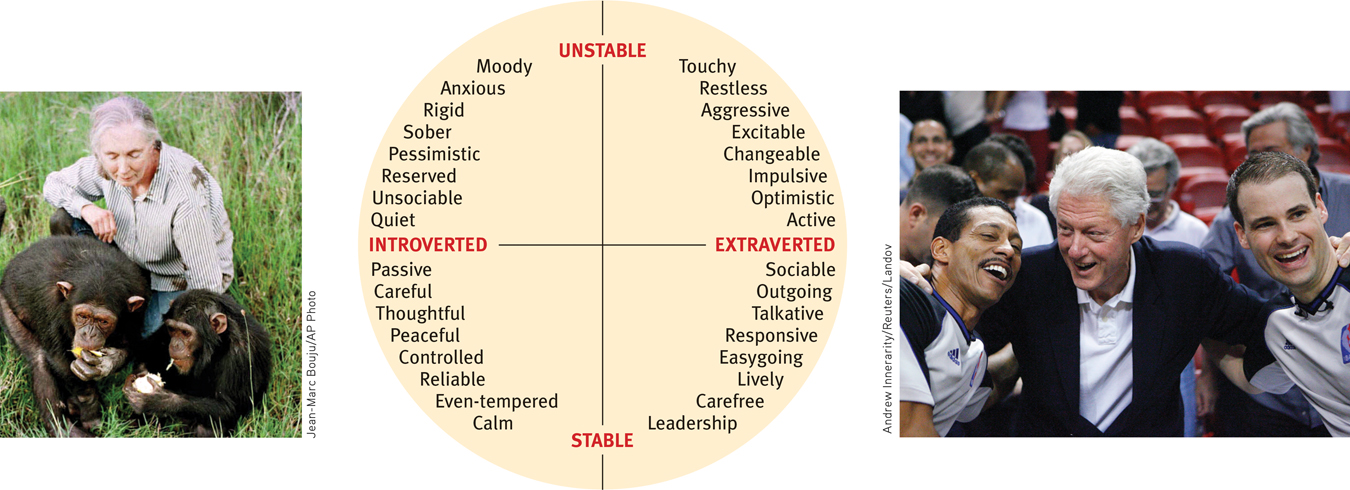

British psychologists Hans Eysenck and Sybil Eysenck [EYE-

Figure 47.1

Figure 47.1Two personality dimensions Mapmakers can tell us a lot by using two axes (north-

Biology and PersonalityBrain-

Our biology influences our personality in other ways as well. As we know from twin and adoption studies, our genes have much to say about the temperament and behavioral style that help define our personality. Jerome Kagan, for example, has attributed differences in children’s shyness and inhibition to their autonomic nervous system reactivity (see Thinking Critically About: The Stigma of Introversion). Those with a reactive autonomic nervous system respond to stress with greater anxiety and inhibition. The fearless, curious child may become the rock-

Personality differences among dogs (in energy, affection, reactivity, and curious intelligence) are as evident, and as consistently judged, as personality differences among humans (Gosling et al., 2003; Jones & Gosling, 2005). Monkeys, chimpanzees, orangutans, and even birds also have stable personalities (Weiss et al., 2006). Among the Great Tit (a European relative of the American chickadee), bold birds more quickly inspect new objects and explore trees (Groothuis & Carere, 2005; Verbeek et al., 1994). By selective breeding, researchers can produce bold or shy birds. Both have their place in natural history: In lean years, bold birds are more likely to find food; in abundant years, shy birds feed with less risk.

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT: The Stigma of Introversion

47-5 What are some common misunderstandings about introversion? Does extraversion lead to greater success than introversion?

Psychologists describe personality, but they don’t advise which traits people should have. Society does this. Western cultures, for example, prize extraversion. Being introverted may imply that you don’t have the “right stuff” (Cain, 2012)

Just look at our superheroes. Extraverted Superman is bold and energetic. His introverted alter ego, Clark Kent, is mild-

TV shows also portray heartthrobs and examples of success as extraverts. Don Draper, the highly successful, attractive advertising executive in the show Mad Men is a classic extravert. He is dominant and charismatic. Women clamor for his attention. Again, the point is plain: Extraversion equals success.

Why do we so often celebrate extraversion and belittle introversion? Many people may not understand what introversion really is. People tend to equate introversion with shyness, but the two concepts differ. Introverted people seek low levels of stimulation from their environment because they’re sensitive. One classic study suggested that introverted people even have greater taste sensitivity. When given lemon juice, introverted people salivated more than extraverted people (Corcoran, 1964). Shy people, in contrast, remain quiet because they fear others will evaluate them negatively.

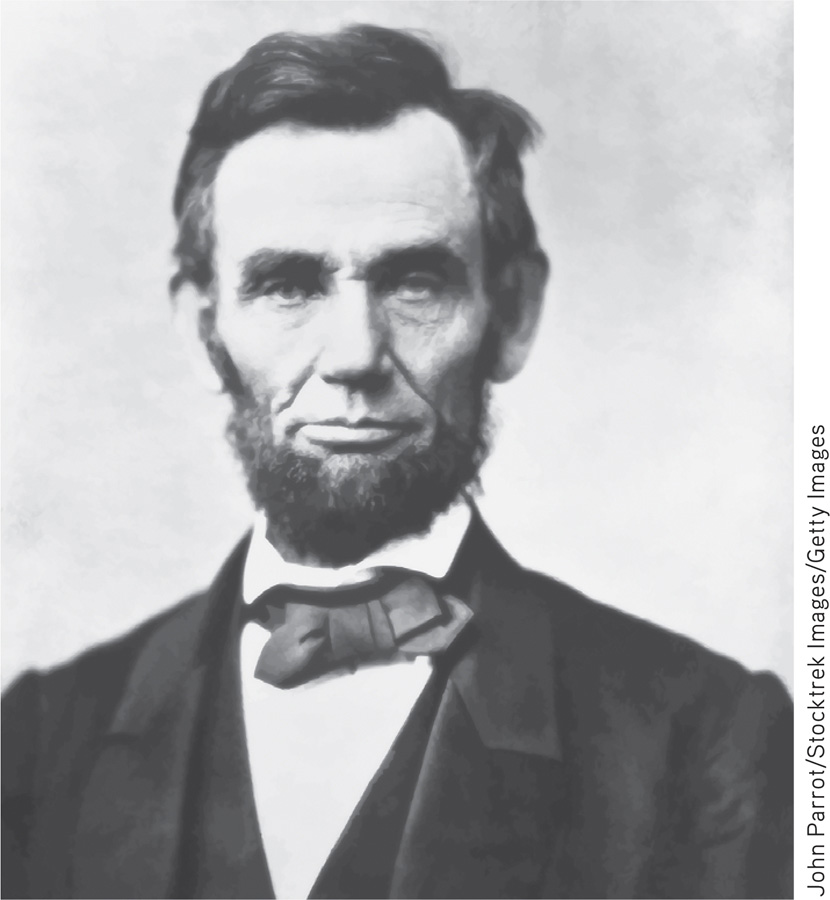

People may also believe that introversion acts as a barrier to success. On the contrary, introversion has its benefits; as supervisors, introverts show greater receptiveness when their employees voice their ideas, challenge existing norms, and take charge. Under these circumstances, introverted leaders outperform extraverted ones (Grant et al., 2011). In fact, one striking analysis of 35 studies showed no correlation between extraversion and sales performance (Barrick et al., 2001) Perhaps the best example of the misperception that introversion hinders career success lies in the American presidency: The American president who is most consistently ranked number one of all time was introverted. His name was Abraham Lincoln.

So, introversion should not be a sign of weakness. Those who need a quiet break from a loud party are not social rejects or incapable of great things. They simply know how to pick an environment where they can thrive. It’s important for extraverts to understand that not everyone needs high levels of stimulation. It’s not a crime to unwind.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Which two primary dimensions did Hans Eysenck and Sybil Eysenck propose for describing personality variation?

Introversion–

Assessing Traits

47-

Might astrology hold the secret to our personality traits? To consider this question, visit LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Astrologers Can Describe People’s Personality?

If stable and enduring traits guide our actions, can we devise valid and reliable tests of them? Several trait assessment techniques exist—

The classic personality inventory is the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI). Although the MMPI was originally developed to identify emotional disorders, it also assesses people’s personality traits. One of its creators, Starke Hathaway (1960), compared his effort to that of Alfred Binet. Binet, the founder of modern intelligence testing, developed the first intelligence test by selecting items that identified children who would probably have trouble progressing normally in French schools. Like Binet’s items, the MMPI items were empirically derived. From a large pool of items, Hathaway and his colleagues selected those on which particular diagnostic groups differed. They then grouped the questions into 10 clinical scales, including scales that assess depressive tendencies, masculinity-

People have had fun spoofing the MMPI with their own mock items: “Weeping brings tears to my eyes,” “Frantic screams make me nervous,” and “I stay in the bathtub until I look like a raisin” (Frankel et al., 1983).

Hathaway and others initially gave hundreds of true-

In contrast to the subjectivity of most projective tests, personality inventories are scored objectively. (Software can administer and score these tests, and can also provide descriptions of people who previously responded similarly.) Objectivity does not, however, guarantee validity. For example, individuals taking the MMPI for employment purposes can give socially desirable answers to create a good impression. But in so doing they may also score high on a lie scale that assesses faking (as when people respond False to a universally true statement such as “I get angry sometimes”). The objectivity of the MMPI has contributed to its popularity and to its translation into more than 100 languages.

The Big Five Factors

47-

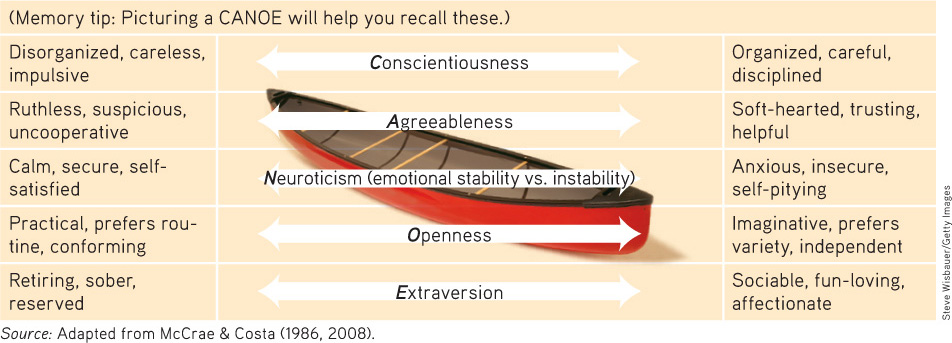

Today’s trait researchers believe that simple trait factors, such as the Eysencks’ introversion-

Table 47.1

Table 47.1The “Big Five” Personality Factors

Researchers use self-

Big Five research has explored various questions:

- How stable are these traits? One research team analyzed 1.25 million participants ages 10 to 65. They learned that personality continues to develop and change through late childhood and adolescence. By adulthood, our traits have become fairly stable, though conscientiousness, agreeableness, openness, and extraversion continue to increase into middle age, and neuroticism (emotional instability) decreases (Soto et al., 2011).

- How heritable are they? Heritability (the extent to which individual differences are attributable to genes) varies with the diversity of people studied, but it generally runs 50 percent or a tad more for each dimension, and genetic influences are similar in different nations (Loehlin et al., 1998; Yamagata et al., 2006). Many genes, each having small effects, combine to influence our traits (McCrae et al., 2010).

- Do these traits reflect differing brain structure? The size of different brain regions correlates with several Big Five traits (DeYoung et al., 2010). For example, those who score high on conscientiousness tend to have a larger frontal lobe area that aids in planning and controlling behavior. Brain connections also influence the Big Five traits (Adelstein et al., 2011). People high in openness have brains that are wired to experience intense imagination, curiosity, and fantasy.

- Have these traits changed over time? Cultures change over time, which can influence shifts in personality. Within the United States and the Netherlands, extraversion and conscientiousness have increased (Mroczek & Spiro, 2003; Smits et al., 2011; Twenge, 2001).

- How well do these traits apply to various cultures? The Big Five dimensions describe personality in various cultures reasonably well (Schmitt et al., 2007; Yamagata et al., 2006). “Features of personality traits are common to all human groups,” concluded Robert McCrae and 79 co-

researchers (2005) from their 50- culture study. - Do the Big Five traits predict our actual behaviors? Yes. If people report being outgoing, conscientious, and agreeable, “they probably are telling the truth,” reports Big Five researcher Robert McCrae (2011). For example, introverts more than extraverts prefer communicating by e-

mail rather than face- to- face (Hertel et al., 2008). Our traits also appear in our language patterns. In text messaging, extraversion predicts use of personal pronouns. Agreeableness predicts positive- emotion words. Neuroticism (emotional instability) predicts negative- emotion words (Holtgraves, 2011).

By exploring such questions, Big Five research has sustained trait psychology and renewed appreciation for the importance of personality. Traits matter.

For an 8-minute demonstration of trait research, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Trait Theories of Personality.

For an 8-minute demonstration of trait research, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Trait Theories of Personality.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What are the Big Five personality factors, and why are they scientifically useful?

The Big Five personality factors are conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism (emotional stability vs. instability), openness, and extraversion (CANOE). These factors may be objectively measured, and research suggests that these factors are relatively stable over the life span and apply to all cultures in which they have been studied.

Evaluating Trait Theories

47-

“There is as much difference between us and ourselves, as between us and others.”

Michel de Montaigne, Essays, 1588

Are our personality traits stable and enduring? Or does our behavior depend on where and with whom we find ourselves? In some ways, our personality seems stable. Cheerful, friendly children tend to become cheerful, friendly adults. At a recent college reunion, I [DM] was amazed to find that my jovial former classmates were still jovial, the shy ones still shy, the happy-

Roughly speaking, the temporary, external influences on behavior are the focus of social psychology, and the enduring, inner influences are the focus of personality psychology. In actuality, behavior always depends on the interaction of persons with situations.

The Person-

Change and consistency can co-exist. If all people were to become somewhat less shy with age, there would be personality change, but also relative stability and predictability.

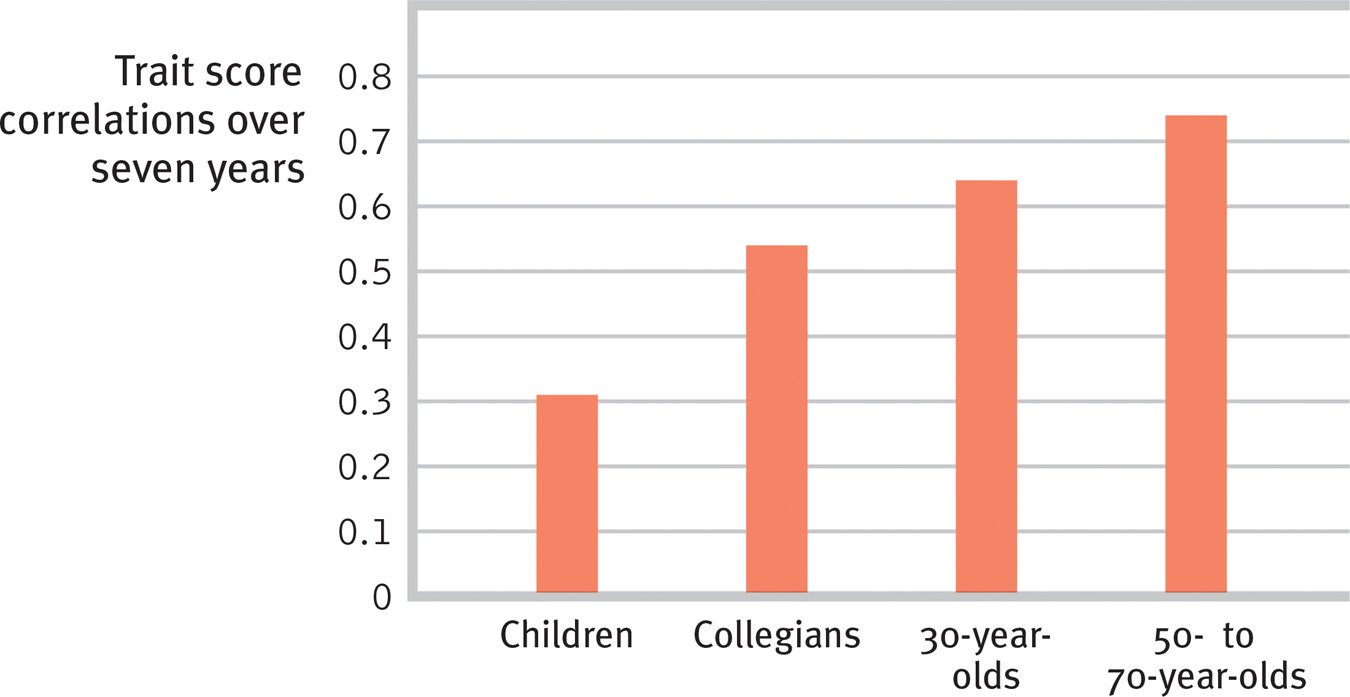

In considering research that has followed lives through time (in longitudinal studies), some scholars (especially those who study infants) are impressed with personality change; others are struck by personality stability during adulthood. As FIGURE 47.2 illustrates, data from 152 long-

Figure 47.2

Figure 47.2Personality stability With age, personality traits become more stable, as reflected in the stronger correlation of trait scores with follow-

So most people—

Any of these tendencies, taken to either extreme, become maladaptive. Agreeableness ranges from cynical combativeness at its low extreme to gullible subservience at its high extreme. Conscientiousness ranges from irresponsible negligence to workaholic perfectionism (Widiger & Costa, 2012).

Although our personality traits may be both stable and potent, the consistency of our specific behaviors from one situation to the next is another matter. As Walter Mischel (1968, 2009) has pointed out, people do not act with predictable consistency. Mischel’s studies of college students’ conscientiousness revealed but a modest relationship between a student’s being conscientious on one occasion (say, showing up for class on time) and being similarly conscientious on another occasion (say, turning in assignments on time). If you’ve noticed how outgoing you are in some situations and how reserved you are in others, perhaps you’re not surprised (though for certain traits, Mischel reports, you may accurately assess yourself as more consistent).

This inconsistency in behaviors also makes personality test scores weak predictors of behaviors. People’s scores on an extraversion test, for example, do not neatly predict how sociable they actually will be on any given occasion. If we remember this, says Mischel, we will be more cautious about labeling and pigeonholing individuals. Years in advance, science can tell us the phase of the Moon for any given date. A day in advance, meteorologists can often predict the weather. But we are much further from being able to predict how you will feel and act tomorrow.

However, people’s average outgoingness, happiness, or carelessness over many situations is predictable (Epstein, 1983a,b). People who know someone well, therefore, generally agree when rating that person’s shyness or agreeableness (Kenrick & Funder, 1988). By collecting snippets of people’s daily experience via body-

- music preferences. Your playlist says a lot about your personality. Classical, jazz, blues, and folk music lovers tend to be open to experience and verbally intelligent. Extraverts tend to prefer upbeat and energetic music. Country, pop, and religious music lovers tend to be cheerful, outgoing, and conscientious (Langmeyer et al., 2012; Rentfrow & Gosling, 2003, 2006).

- bedrooms and offices. Our personal spaces display our identity and leave a behavioral residue (in our scattered laundry or neat desktop). After just a few minutes’ inspection of our living and working spaces, a visitor could give a fairly accurate summary of our conscientiousness, our openness to new experiences, and even our emotional stability (Gosling et al., 2002, 2008).

- online spaces. Is a personal website, social media profile, or instant messaging account also a canvas for self-expression? Or is it an opportunity for people to present themselves in false or misleading ways? It’s more the former (Back et al., 2010; Gosling et al., 2007; Marcus et al., 2006). Viewers quickly gain important clues to the creator’s extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness to experience. Even mere pictures of people, and their associated clothes, expressions, and postures, can give clues to personality (Naumann et al., 2009).

- written communications. If you have ever felt you could detect someone’s personality from their writing voice, you are right!! (What a cool, exciting finding!!! … if you catch our drift.) People’s ratings of others’ personalities based solely on what they’ve written correlate with actual personality scores on measures such as extraversion and neuroticism (Gill et al., 2006; Oberlander & Gill, 2006; Pennebaker, 2011; Yarkoni, 2010). Extraverts, for example, use more adjectives.

In unfamiliar, formal situations—

Some people are naturally expressive (and therefore talented at pantomime and charades); others are less expressive (and therefore better poker players). To evaluate people’s voluntary control over their expressiveness, Bella DePaulo and her colleagues (1992) asked people to act as expressive or inhibited as possible while stating opinions. Their remarkable findings: Inexpressive people, even when feigning expressiveness, were less expressive than expressive people acting naturally. Similarly, expressive people, even when trying to seem inhibited, were less inhibited than inexpressive people acting naturally. It’s hard to be someone you’re not, or not to be who you are.

To sum up, we can say that at any moment the immediate situation powerfully influences a person’s behavior. Social psychologists have learned that this is especially so when a “strong situation” makes clear demands (Cooper & Withey, 2009). We can better predict drivers’ behavior at traffic lights from knowing the color of the lights than from knowing the drivers’ personalities. Thus, professors may perceive certain students as subdued (based on their classroom behavior), but friends may perceive them as pretty wild (based on their party behavior). Averaging our behavior across many occasions does, however, reveal distinct personality traits. Traits exist. We differ. And our differences matter.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How well do personality test scores predict our behavior? Explain.

Our scores on personality tests predict our average behavior across many situations much better than they predict our specific behavior in any given situation.