49.3 Classifying Disorders—and Labeling People

49-

In biology, classification creates order. To classify an animal as a “mammal” says a great deal—

But diagnostic classification gives more than a thumbnail sketch of a person’s disordered behavior, thoughts, or feelings. In psychiatry and psychology, classification also aims to

- predict the disorder’s future course.

- suggest appropriate treatment.

- prompt research into its causes.

To study a disorder, we must first name and describe it.

A book of case illustrations accompanying the previous DSM edition provided several examples for Modules 49 through 53.

The most common tool for describing disorders and estimating how often they occur is the American Psychiatric Association’s 2013 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, now in its fifth edition (DSM-5). Physicians and mental health workers use the detailed “diagnostic criteria and codes” in the DSM-

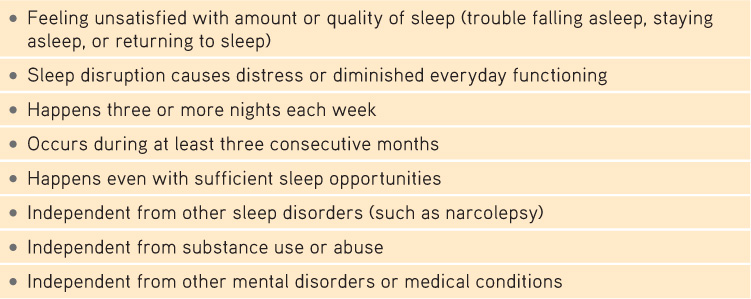

Table 49.1

Table 49.1Insomnia Disorder

In the DSM-

Some of the new or altered diagnoses are controversial. Disruptive mood dysregula-

Real-

Critics have long faulted the DSM for casting too wide a net and bringing “almost any kind of behavior within the compass of psychiatry” (Eysenck et al., 1983). Some now worry that the DSM-

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT: ADHD—Normal High Energy or Disordered Behavior?

49-4 Why is there controversy over attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder?

Eight-

If taken for a psychological evaluation, Todd may be diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Some 11 percent of American 4-

To skeptics, being distractible, fidgety, and impulsive sounds like a “disorder” caused by a single genetic variation: a Y chromosome (the male sex chromosome). And sure enough, ADHD is diagnosed three times more often in boys than in girls. Children who are “a persistent pain in the neck in school” are often diagnosed with ADHD and given powerful prescription drugs (Gray, 2010). Minority youth less often receive an ADHD diagnosis than do Caucasian youth, but this difference has shrunk as minority ADHD diagnoses have increased (Getahun et al., 2013).

The problem may reside less in the child than in today’s abnormal environment that forces children to do what evolution has not prepared them to do—

Rates of medication for presumed ADHD vary by age, sex, and location. Prescription drugs are more often given to teens than to younger children. Boys are nearly three times more likely to receive them than are girls. And location matters. Among 4-

Not everyone agrees that ADHD is being overdiagnosed. Some argue that today’s more frequent diagnoses reflect increased awareness of the disorder, especially in those areas where rates are highest. They also note that diagnoses can be inconsistent—

What, then, is known about ADHD’s causes? It is not caused by too much sugar or poor schools. There is mixed evidence suggesting that extensive TV watching and video gaming are associated with reduced cognitive self-

The bottom line: Extreme inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity can derail social, academic, and vocational achievements, and these symptoms can be treated with medication and other therapies. But the debate continues over whether normal high energy is too often diagnosed as a psychiatric disorder, and whether there is a cost to the long-

Other critics register a more basic complaint—

The biasing power of labels was clear in a now-

Should we be surprised? As one psychiatrist noted, if someone swallows blood, goes to an emergency room, and spits it up, should we fault the doctor for diagnosing a bleeding ulcer? Surely not. But what followed the Rosenhan study diagnoses was startling. Until being released an average of 19 days later, those eight “patients” showed no other symptoms. Yet after analyzing their (quite normal) life histories, clinicians were able to “discover” the causes of their disorders, such as having mixed emotions about a parent. Even routine note-

Labels matter. In another study, people watched videotaped interviews. If told the interviewees were job applicants, the viewers perceived them as normal (Langer et al., 1974, 1980). Other viewers who were told they were watching psychiatric or cancer patients perceived the same interviewees as “different from most people.” Therapists who thought they were watching an interview of a psychiatric patient perceived him as “frightened of his own aggressive impulses,” a “passive, dependent type,” and so forth. A label can, as Rosenhan discovered, have “a life and an influence of its own.”

“My sister suffers from a bipolar disorder and my nephew from schizoaffective disorder. There has, in fact, been a lot of depression and alcoholism in my family and, traditionally, no one ever spoke about it. It just wasn’t done. The stigma is toxic.”

Actress Glenn Close, “Mental Illness: The Stigma of Silence,” 2009

Labels also have power outside the laboratory. Getting a job or finding a place to rent can be a challenge for people recently released from a mental hospital. Label someone as “mentally ill” and people may fear them as potentially violent (see Thinking Critically About: Are People With Psychological Disorders Dangerous?) Such negative reactions may fade as people better understand that many psychological disorders involve diseases of the brain, not failures of character (Solomon, 1996). Public figures have helped foster this new understanding by speaking openly about their own struggles with disorders such as depression and substance abuse. The more contact we have with people with disorders, the more accepting our attitudes are (Kolodziej & Johnson, 1996).

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT: Are People With Psychological Disorders Dangerous?

49-5 Do psychological disorders predict violent behavior?

September 16, 2013, started like any other Monday at Washington, DC’s, Navy Yard, with people arriving early to begin work. Then government contractor Aaron Alexis parked his car, entered the building, and began shooting people. An hour later, 13 people were dead, including Alexis. Reports later confirmed that Alexis had a history of mental illness. Before the shooting, he had stated that an “ultra low frequency attack is what I’ve been subject to for the last three months. And to be perfectly honest, that is what has driven me to this.” This devastating mass shooting, like the one in a Connecticut elementary school in 2012 and many others since then, reinforced public perceptions that people with psychological disorders pose a threat (Jorm et al., 2012). After the 2012 slaughter, New York’s governor declared, “People who have mental issues should not have guns” (Kaplan & Hakim, 2013).

Does scientific evidence support the governor’s statement? If disorders actually increase the risk of violence, then denying people with psychological disorders the right to bear arms might reduce violent crimes. But real life tells a different story. The vast majority of violent crimes are committed by people with no diagnosed disorder (Fazel & Grann, 2006; Walkup & Rubin, 2013).

People with disorders are more likely to be victims than perpetrators of violence (Marley & Bulia, 2001). According to the U.S. Surgeon General’s Office (1999, p. 7), “There is very little risk of violence or harm to a stranger from casual contact with an individual who has a mental disorder.” People with mental illness commit proportionately little gun violence. The bottom line: Focusing gun restrictions only on mentally ill people will likely not reduce gun violence (Friedman, 2012).

If mental illness is not a good predictor of violence, what is? Better predictors are a history of violence, use of alcohol or drugs, and access to a gun. The mass-

Mental disorders seldom lead to violence, and clinical prediction of violence is unreliable. What, then, are the triggers for the few people with psychological disorders who do commit violent acts? For some, the trigger is substance abuse. For others, like the Navy Yard shooter, it’s threatening delusions and hallucinated voices that command them to act (Douglas et al., 2009; Elbogen & Johnson, 2009; Fazel et al., 2009, 2010). Whether people with mental disorders who turn violent should be held responsible for their behavior remains controversial. U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s near-

Which decision was correct? The first two, which blamed Loughner’s “madness” for clouding his judgment? Or the final one, which decided that he should be held responsible for the acts he committed? As we come to better understand the biological and environmental bases for all human behavior, from generosity to vandalism, when should we—

“What’s the use of their having names,” the Gnat said, “if they won’t answer to them?”

“No use to them,” said Alice; “but it’s useful to the people that name them, I suppose.”

Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass, 1871

Despite their risks, diagnostic labels have benefits. Mental health professionals use labels to communicate about their cases, to comprehend the underlying causes, and to discern effective treatment programs. Researchers use labels when discussing work that explores the causes and treatments of disorders. Clients are often relieved to learn that the nature of their suffering has a name, and that they are not alone in experiencing this collection of symptoms.

To test your ability to form diagnoses, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Classifying Disorders.

To test your ability to form diagnoses, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Classifying Disorders.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is the value, and what are the dangers, of labeling individuals with disorders?

Therapists and others use disorder labels to communicate with one another using a common language, and to share concepts during research. Clients may benefit from knowing that they are not the only ones with these symptoms. The dangers of labeling people are that (1) people may begin to act as they have been labeled, and (2) the labels can trigger assumptions that will change our behavior toward those we label.