50.4 Understanding Anxiety Disorders, OCD, and PTSD

50-

Anxiety is both a feeling and a cognition—

Conditioning

Some bad events come with a warning. Your underdog team might lose the big game. You aren’t prepared and you may fail your quiz. You’re running late and might miss the bus. But when bad events happen unpredictably and uncontrollably, anxiety and other disorders often develop (Field, 2006; Mineka & Oehlberg, 2008). In a classic experiment, an infant called “Little Albert” learned to fear furry objects that were paired with loud noises. In other experiments, researchers have created anxious animals by giving rats unpredictable electric shocks (Schwartz, 1984). The rats, like assault victims who report feeling anxious when returning to the scene of the crime, became uneasy in their lab environment. The lab had become a cue for fear.

Such research helps explain why anxious people are hyperattentive to possible threats, and how panic-

Through conditioning, the short list of naturally painful and frightening events can multiply into a long list of human fears. Can you recall a frightening event that left you fearful for a while? We can. I [DM] was headed home when my car was struck by another when its driver missed a stop sign. For months afterward, I felt a twinge of unease as a car approached from a side street. Likewise, I [ND] remember watching a terrifying movie about spiders, Arachnophobia, when a severe thunderstorm struck and the theater lost power. For months, I experienced anxiety at the sight of spiders or harmless cobwebs.

How might conditioning magnify a single painful and frightening event into a fullblown phobia? The answer lies in part in two conditioning processes: stimulus generalization and reinforcement.

Stimulus generalization occurs when a person experiences a fearful event and later develops a fear of similar events. Each of us [DM and ND] generalized our fears: One of us feared cars approaching from side streets and the other feared spiders. Those fears eventually disappeared, but sometimes fears can linger and grow. Marilyn’s thunderstorm phobia may have similarly generalized after a terrifying or painful experience during a thunderstorm.

Once fears and anxieties arise, reinforcement helps maintain them. Anything that helps us avoid or escape the feared situation can be reinforcing because it reduces anxiety and gives us a feeling of relief. Fearing a panic attack, we may decide not to leave the house. Reinforced by feeling calmer, we are likely to repeat that maladaptive behavior in the future (Antony et al., 1992). So, too, with compulsive behaviors. If washing our hands relieves our feelings of anxiety, we may wash our hands again when those feelings return.

Cognition

Conditioning influences our feelings of anxiety, but so does cognition—

Our past experiences shape our expectations and influence our interpretations and reactions. Whether we interpret the creaky sound in the old house simply as the wind or as a possible knife-

Biology

There is, however, more to anxiety disorders, OCD, and PTSD than conditioning and cognitive processes alone. Why will some of us develop lasting phobias or PTSD after suffering traumas? Why do we all learn some fears so readily? Why are some of us more vulnerable? The biological perspective offers insight.

GenesGenes matter. Pair a traumatic event with a sensitive, high-

Among monkeys, fearfulness runs in families. A monkey reacts more strongly to stress if its close biological relatives are anxiously reactive (Suomi, 1986). So, too, with people. If one identical twin has an anxiety disorder, the other is likewise at risk (Hettema et al., 2001; Kendler et al., 2002a,b; Van Houtem et al., 2013). Even when raised separately, identical twins may develop similar phobias (Carey, 1990; Eckert et al., 1981). One pair of 35-

Given the genetic contribution to anxiety disorders, researchers are now sleuthing the culprit genes. One research team identified 17 gene variations associated with typical anxiety disorder symptoms (Hovatta et al., 2005). Other teams have found genes associated specifically with OCD (Taylor, 2013).

Genes can influence disorders by regulating neurotransmitters. Some studies point to an “anxiety gene” that affects brain levels of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that influences sleep, mood, and attention to negative images (Canli, 2008; Pergamin-

Among PTSD patients, a history of child abuse leaves long-

The BrainOur experiences change our brain, paving new pathways. Traumatic fear-

Anxiety-

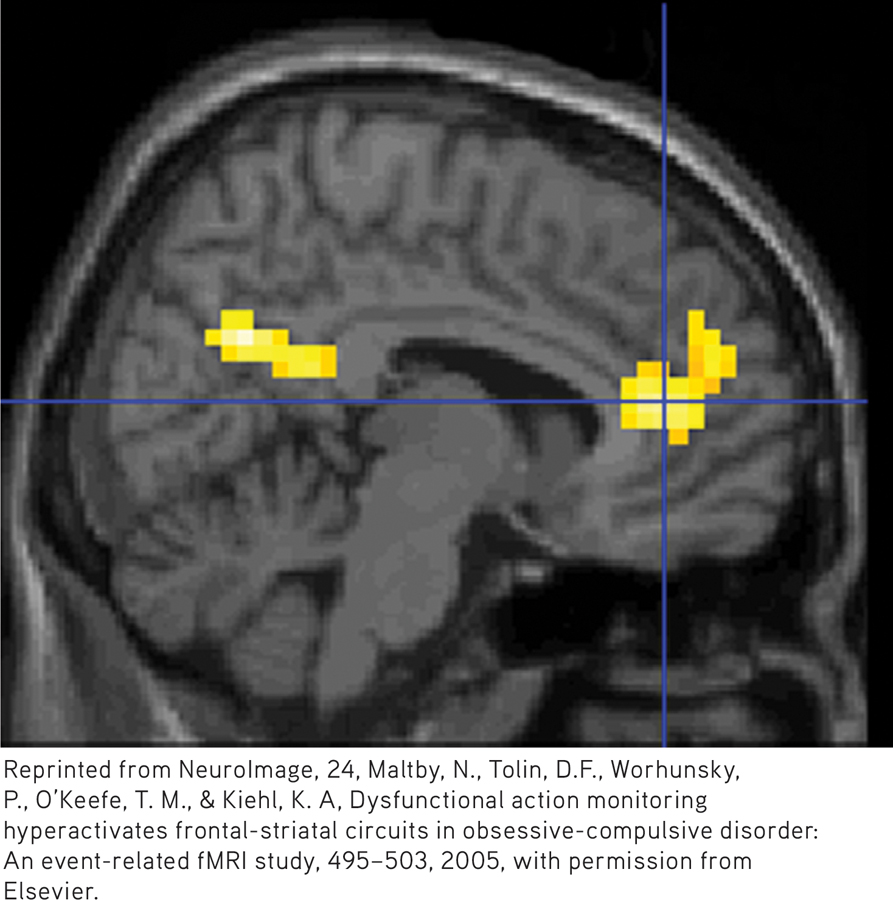

Figure 50.2

Figure 50.2An obsessive-

Some antidepressant drugs dampen this fear-

Natural SelectionWe seem biologically prepared to fear threats faced by our ancestors. Our phobias focus on such specific fears: spiders, snakes, and other animals; enclosed spaces and heights; storms and darkness. (Those fearless about these occasional threats were less likely to survive and leave descendants.) Thus, even in Britain, with only one poisonous snake species, people often fear snakes. It is easy to condition and hard to extinguish fears of such “evolutionarily relevant” stimuli (Coelho & Purkis, 2009; Davey, 1995; Öhman, 2009). Some of our modern fears can also have an evolutionary explanation. A fear of flying may be rooted in our biological predisposition to fear confinement and heights.

Compare our easily conditional fears to what we do not easily learn to fear. World War II air raids, for example, produced remarkably few lasting phobias. As the air blitzes continued, the British, Japanese, and German populations did not become more and more panicked. Rather, they grew more indifferent to planes outside their immediate neighborhoods (Mineka & Zinbarg, 1996). Evolution has not prepared us to fear bombs dropping from the sky.

Just as our phobias focus on dangers faced by our ancestors, our compulsive acts typically exaggerate behaviors that contributed to our species’ survival. Grooming gone wild becomes hair pulling. Washing up becomes ritual hand washing. Checking territorial boundaries becomes rechecking an already locked door (Rapoport, 1989).

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Researchers believe that conditioning and cognitive processes contribute to anxiety disorders, OCD, and PTSD. What biological factors also contribute to these disorders?

Biological factors include inherited temperament differences and other gene variations; learned fears that have altered brain pathways; and outdated, inherited responses that had survival value for our distant ancestors.