52.3 Understanding Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a dreaded psychological disorder. It is also one of the most heavily researched. Most studies now link it with abnormal brain tissue and genetic predispositions. Schizophrenia is a disease of the brain manifested in symptoms of the mind.

Brain Abnormalities

52-

Might chemical imbalances in the brain underlie schizophrenia? Scientists have long known that strange behavior can have strange chemical causes. The saying “mad as a hatter” refers to the psychological deterioration of British hatmakers whose brains, it was later discovered, were slowly poisoned as they moistened the brims of mercury-

Dopamine OveractivityOne possible answer emerged when researchers examined schizophrenia patients’ brains after death. They found an excess of receptors for dopamine—a sixfold excess for the dopamine receptor D4 (Seeman et al., 1993; Wong et al., 1986). Such a hyper-

Most people with schizophrenia smoke, often heavily. Nicotine apparently stimulates certain brain receptors, which helps focus attention (Diaz et al., 2008; Javitt & Coyle, 2004).

Abnormal Brain Activity and AnatomyBrain scans show that abnormal activity accompanies schizophrenia. Some people diagnosed with schizophrenia have abnormally low brain activity in the frontal lobes, areas that help us reason, plan, and solve problems (Morey et al., 2005; Pettegrew et al., 1993; Resnick, 1992). Brain scans also show a noticeable decline in the brain waves that reflect synchronized neural firing in the frontal lobes (Spencer et al., 2004; Symond et al., 2005). Out-

One study took PET scans of brain activity while people were hallucinating (Sil-

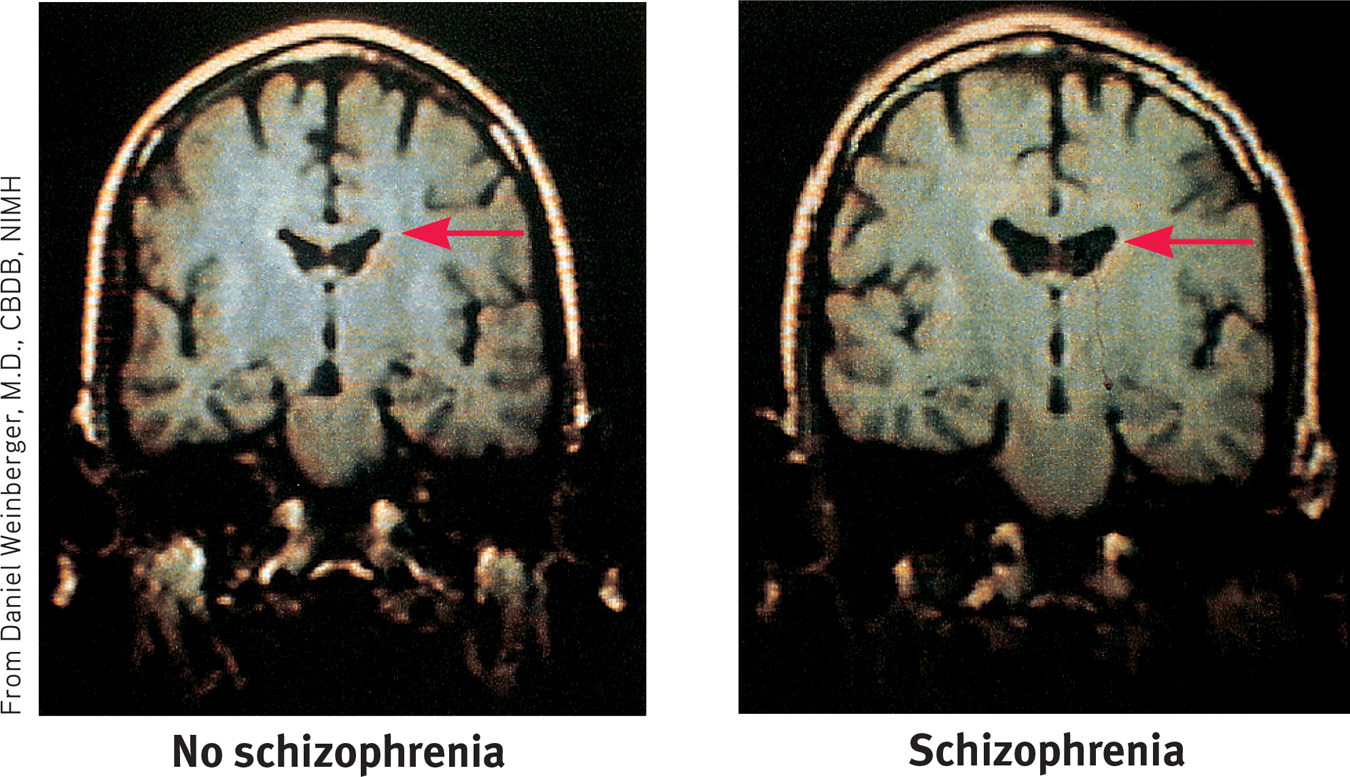

Many studies have found enlarged, fluid-

Two smaller-

Prenatal Environment and Risk

52-

What causes brain abnormalities in people with schizophrenia? Some scientists point to mishaps during prenatal development or delivery (Fatemi & Folsom, 2009; Walker et al., 2010). Risk factors for schizophrenia include low birth weight, maternal diabetes, older paternal age, and oxygen deprivation during delivery (King et al., 2010). Famine may also increase risks. People conceived during the peak of World War II’s Dutch wartime famine later developed schizophrenia at twice the normal rate. Those conceived during the famine of 1959 to 1961 in eastern China also displayed this doubled rate (St. Clair et al., 2005; Susser et al., 1996).

Let’s consider another possible culprit. Might a midpregnancy viral infection impair fetal brain development (Brown & Patterson, 2011)? Can you imagine some ways to test this fetal-

- Are people at increased risk of schizophrenia if, during the middle of their fetal development, their country experienced a flu epidemic? The repeated answer has been Yes (Mednick et al., 1994; Murray et al., 1992; Wright et al., 1995).

- Are people born in densely populated areas, where viral diseases spread more readily, at greater risk for schizophrenia? The answer, confirmed in a study of 1.75 million Danes, has again been Yes (Jablensky, 1999; Mortensen, 1999).

- Are those born during the winter and spring months—after the fall-winter flu season—also at increased risk? Although the increase is small, just 5 to 8 percent, the answer has been Yes (Fox, 2010; Schwartz, 2011; Torrey et al., 1997, 2002).

- In the Southern Hemisphere, where the seasons are the reverse of the Northern Hemisphere, are the months of above-average schizophrenia births similarly reversed? Again, the answer has been Yes, though somewhat less so. In Australia, people born between August and October are at greater risk. But there is an exception: For people born in the Northern Hemisphere, who later moved to Australia, the risk is greater if they were born between January and March (McGrath et al., 1995, 1999).

- Are mothers who report being sick with influenza during pregnancy more likely to bear children who develop schizophrenia? In one study of nearly 8000 women, the answer was Yes. The schizophrenia risk increased from the customary 1 percent to about 2 percent—but only when infections occurred during the second trimester (Brown et al., 2000). Maternal influenza infection during pregnancy affects brain development in monkeys also (Short et al., 2010).

- Does blood drawn from pregnant women whose offspring develop schizophrenia show higher-than-normal levels of antibodies that suggest a viral infection? In one study of 27 women whose children later developed schizophrenia, the answer was Yes (Buka et al., 2001). And the answer was again Yes in a huge California study, which collected blood samples from some 20,000 pregnant women during the 1950s and 1960s (Brown et al., 2004). Another study found traces of a specific retrovirus (HERV) in nearly half of people with schizophrenia and virtually none in healthy people (Perron et al., 2008).

These converging lines of evidence suggest that fetal-

Why might a second-

Genetic Factors

52-

Fetal-

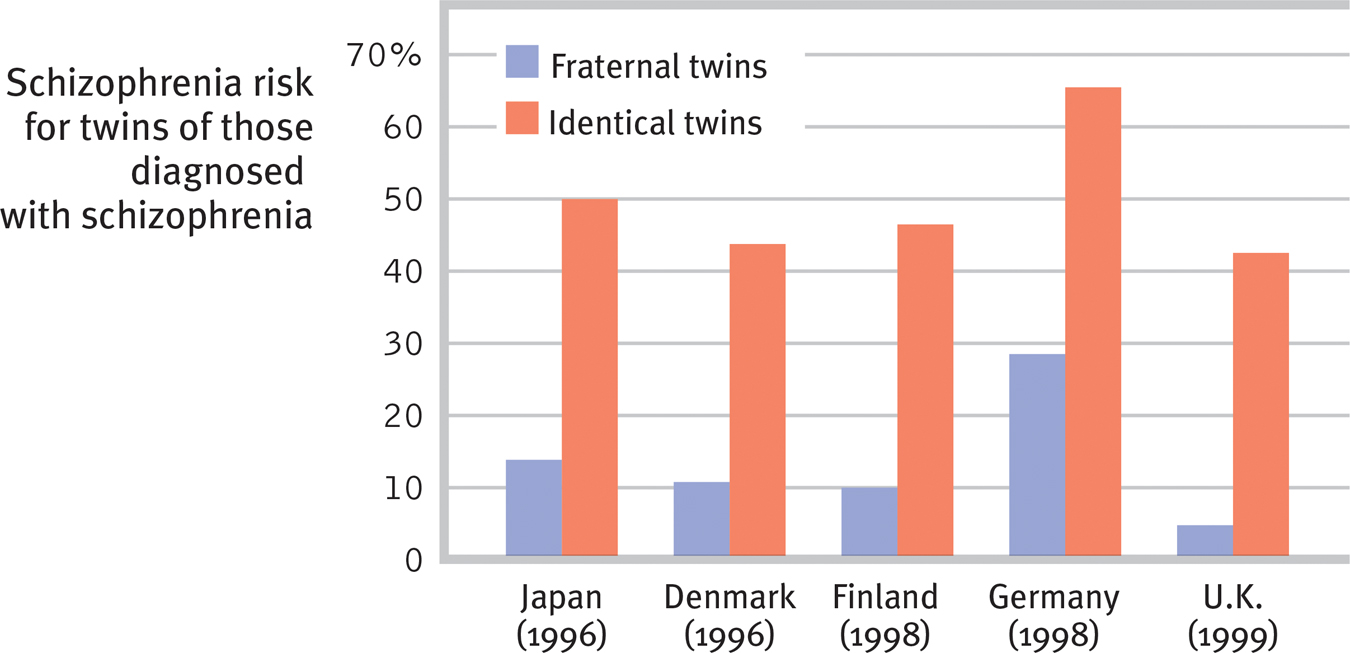

Figure 52.1

Figure 52.1Risk of developing schizophrenia The lifetime risk of developing schizophrenia varies with one’s genetic relatedness to someone having this disorder. Across countries, barely more than 1 in 10 fraternal twins, but some 5 in 10 identical twins, share a schizophrenia diagnosis. (Data from Gottesman, 2001.)

Remember, though, that identical twins share more than their genes. They also share a prenatal environment. About two-

Adoption studies help untangle genetic and environmental influences. Children adopted by someone who develops schizophrenia seldom “catch” the disorder. Rather, adopted children have an elevated risk if a biological parent is diagnosed with schizophrenia (Gottesman, 1991).

The search is on for specific genes that, in some combination, predispose schizophrenia-

Although genes matter, the genetic formula is not as straightforward as the inheritance of eye color. Genome studies of thousands of individuals with and without schizophrenia indicate that schizophrenia is influenced by many genes, each with very small effects (International Schizophrenia Consortium, 2009; Xu et al., 2012). And, as we have so often seen, nature and nurture interact. Epigenetic (literally “in addition to genetic”) factors influence whether or not genes will be expressed. Like hot water activating a tea bag, environmental factors such as viral infections, nutritional deprivation, and maternal stress can “turn on” the genes that put some of us at higher risk for schizophrenia. Identical twins’ differing histories in the womb and beyond explain why only one of them may show differing gene expressions (Dempster et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2010). Our heredity and our life experiences work together. Neither hand claps alone.

Consider how researchers have studied these issues with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Schizophrenia is Inherited?

Thanks to our expanding understanding of genetic and brain influences on maladies such as schizophrenia, the general public more and more attributes psychiatric disorders to biological factors (Pescosolido et al., 2010). In 2007, one privately funded new research center announced its ambitious aim: “To unambiguously diagnose patients with psychiatric disorders based on their DNA sequence in 10 years’ time” (Holden, 2007). In 2010, $120 million in start-

Environmental Triggers for Schizophrenia

If prenatal viruses and genetic predispositions do not, by themselves, cause schizophrenia, neither do family or social factors alone. It remains true, as Susan Nicol and Irving Gottesman (1983) noted over three decades ago, that “no environmental causes have been discovered that will invariably, or even with moderate probability, produce schizophrenia in persons who are not related to” a person with schizophrenia.

Hoping to identify environmental triggers of schizophrenia, researchers have compared the experiences of high-

- A mother whose schizophrenia was severe and long-lasting

- Birth complications, often involving oxygen deprivation and low birth weight

- Separation from parents

- Short attention span and poor muscle coordination

- Disruptive or withdrawn behavior

- Emotional unpredictability

- Poor peer relations and solo play

- Childhood physical, sexual, or emotional abuse

Few of us can relate to the strange thoughts, perceptions, and behaviors of schizophrenia. Sometimes our thoughts jump around, but we rarely talk nonsensically. Occasionally we feel unjustly suspicious of someone, but we do not fear that the world is plotting against us. Often our perceptions err, but rarely do we see or hear things that are not there. We feel regret after laughing at someone’s misfortune, but we rarely giggle in response to bad news. At times we just want to be alone, but we do not live in social isolation. However, millions of people around the world do talk strangely, suffer delusions, hear nonexistent voices, see things that are not there, laugh or cry at inappropriate times, or withdraw into private imaginary worlds. The quest to solve the cruel puzzle of schizophrenia continues, more vigorously than ever.

For an 8-minute description of how clinicians define and treat schizophrenia, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Schizophrenia–New Definitions, New Therapies.

For an 8-minute description of how clinicians define and treat schizophrenia, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Schizophrenia–New Definitions, New Therapies.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- A person with schizophrenia who has __________ (positive/negative) symptoms may have an expressionless face and toneless voice. These symptoms are most common with __________ (chronic /acute) schizophrenia and are not likely to respond to drug therapy. Those with __________ (positive/negative) symptoms are likely to experience delusions and to be diagnosed with __________ (chronic /acute) schizophrenia, which is much more likely to respond to drug therapy.

negative; chronic; positive; acute

- What factors contribute to the onset and development of schizophrenia?

Biological factors include abnormalities in brain structure and function, prenatal exposure to a maternal virus, and a genetic predisposition to the disorder. However, a high-