53.2 Personality Disorders

53-

The disruptive, inflexible, and enduring behavior patterns of personality disorders interfere with social functioning. These disorders tend to form three clusters, characterized by

- anxiety, such as a fearful sensitivity to rejection that predisposes the withdrawn avoidant personality disorder.

- eccentric or odd behaviors, such as the emotionless disengagement of schizotypal personality disorder.

- dramatic or impulsive behaviors, such as the attention-getting borderline personality disorder, the self-focused and self-inflating narcissistic personality disorder, and the callous, and sometimes dangerous, antisocial personality disorder.

Antisocial Personality Disorder

A person with antisocial personality disorder is typically a male whose lack of conscience becomes plain before age 15, as he begins to lie, steal, fight, or display unrestrained sexual behavior (Cale & Lilienfeld, 2002). About half of such children become antisocial adults—

Despite their remorseless and sometimes criminal behavior, criminality is not an essential component of antisocial behavior (Skeem & Cooke, 2010). Moreover, many criminals do not fit the description of antisocial personality disorder. Why? Because they actually show responsible concern for their friends and family members.

Antisocial personalities behave impulsively, and then feel and fear little (Fowles & Dindo, 2009). Their impulsivity can have violent, horrifying consequences (Camp et al., 2013). Consider the case of Henry Lee Lucas. He killed his first victim when he was 13. He felt little regret then or later. He confessed that, during his 32 years of crime, he had brutally beaten, suffocated, stabbed, shot, or mutilated some 360 women, men, and children. For the last six years of his reign of terror, Lucas teamed with Ottis Elwood Toole, who reportedly slaughtered about 50 people he “didn’t think was worth living anyhow” (Darrach & Norris, 1984).

Understanding Antisocial Personality Disorder

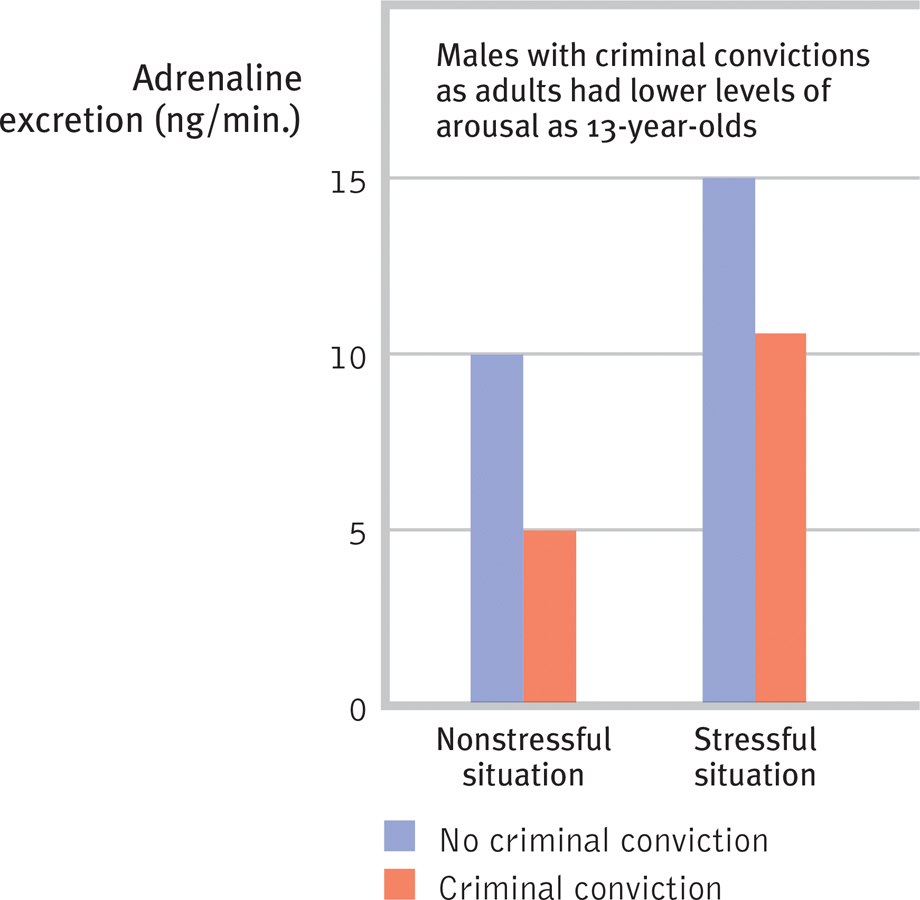

Antisocial personality disorder is woven of both biological and psychological strands. Twin and adoption studies reveal that biological relatives of people with antisocial and unemotional tendencies are at increased risk for antisocial behavior (Frisell et al., 2012; Tuvblad et al., 2011). No single gene codes for a complex behavior such as crime. Molecular geneticists have, however, identified some specific genes that are more common in those with antisocial personality disorder (Gunter et al., 2010). The genetic vulnerability of people with antisocial and unemotional tendencies appears as a fearless approach to life. Awaiting aversive events, such as electric shocks or loud noises, they show little autonomic nervous system arousal (Hare, 1975; van Goozen et al., 2007). Long-

Figure 53.1

Figure 53.1Cold-

Traits such as fearlessness and dominance can be adaptive. In fact, some argue that psychopaths and heroes are twigs off the same branch (Smith et al., 2013). If channeled in more productive directions, fearlessness may lead to star-

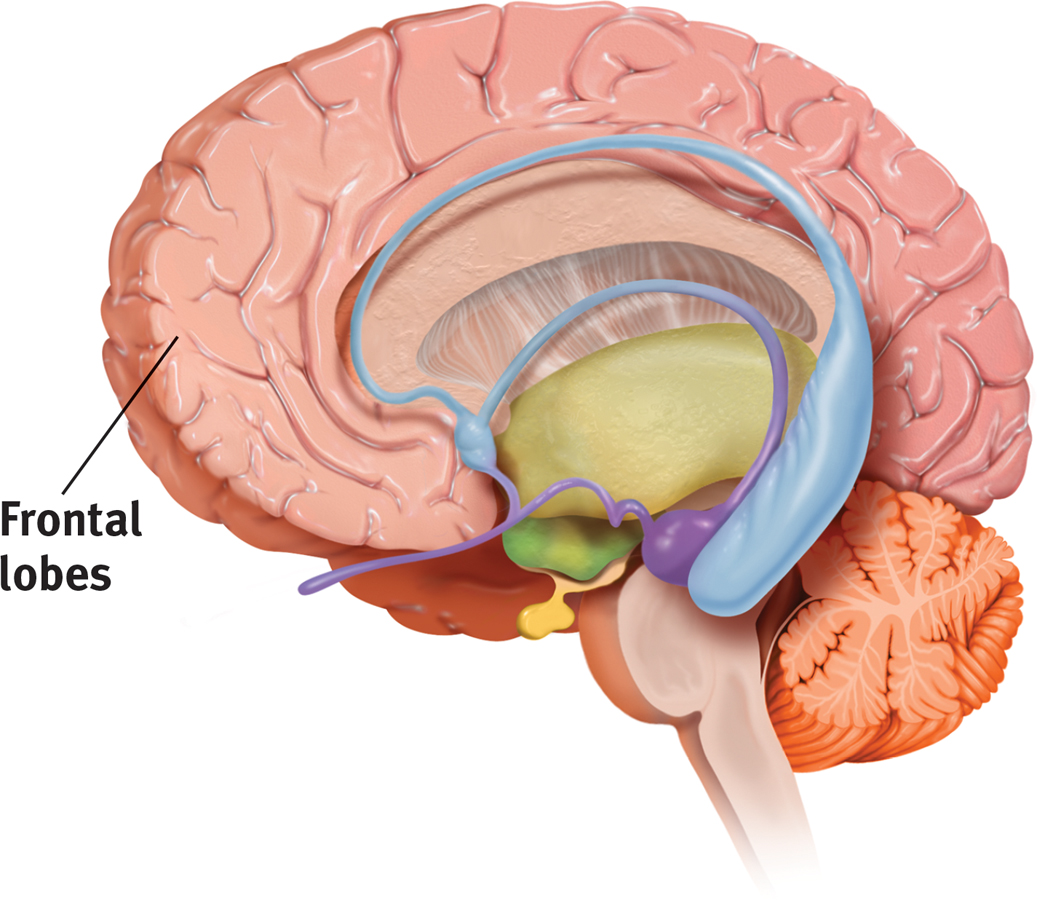

Genetic influences, often in combination with child abuse, help wire the brain (Dodge, 2009). In people with antisocial criminal tendencies, the emotion-

Figure 53.2

Figure 53.2Murderous minds Researchers have found reduced activation in a murderer’s frontal lobes. This brain area (shown in a left-

Does a full Moon trigger “madness” in some people? James Rotton and I. W. Kelly (1985) examined data from 37 studies that related lunar phase to crime, homicides, crisis calls, and mental hospital admissions. Their conclusion: There is virtually no evidence of “Moon madness.” Nor does lunar phase correlate with suicides, assaults, emergency room visits, or traffic disasters (Martin et al., 1992; Raison et al., 1999).

A biologically based fearlessness, as well as early environment, helps explain the reunion of long-

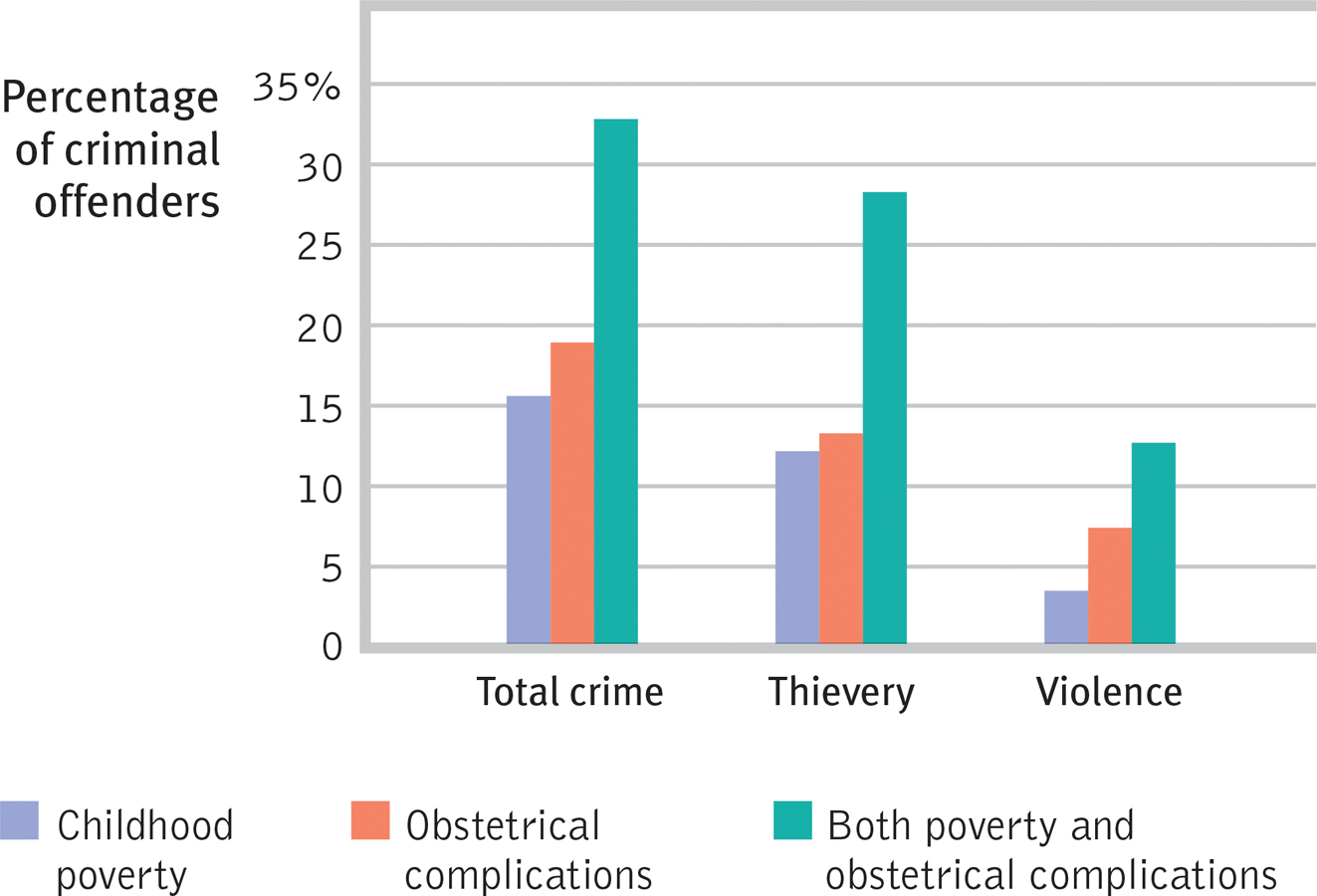

Genetics alone do not tell the whole story of antisocial crime, however. In another Raineled study (1996), researchers checked criminal records on nearly 400 Danish men at ages 20 to 22. All these men either had experienced biological risk factors at birth (such as premature birth) or came from family backgrounds marked by poverty and family instability. The researchers then compared each of these two groups with a third biosocial group (people whose lives were marked by both those biological and social risk factors). The biosocial group had double the risk of committing crime (FIGURE 53.3). Similar findings emerged from a famous study that followed 1037 children for a quarter-

Figure 53.3

Figure 53.3Biopsychosocial roots of crime Danish male babies whose backgrounds were marked both by obstetrical complications and social stresses associated with poverty were twice as likely to be criminal offenders by ages 20 to 22 as those in either the biological or social risk groups. (Data from Raine et al., 1996.)

With antisocial behavior, as with so much else, nature and nurture interact and the biopsychosocial perspective helps us understand the whole story. To explore the neural basis of antisocial personality disorder, neuroscientists are trying to identify brain activity differences in criminals who display symptoms of this disorder. Shown emotionally evocative photographs, such as a man holding a knife to a woman’s throat, criminals with antisocial personality disorder display blunted heart rate and perspiration responses, and less activity in brain areas that typically respond to emotional stimuli (Harenski et al., 2010; Kiehl & Buckholtz, 2010). They also have a larger and hyper-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How do biological and psychological factors contribute to antisocial personality disorder?

Twin and adoption studies show that biological relatives of people with this disorder are at increased risk for antisocial behavior. Negative environmental factors, such as poverty or childhood abuse, may channel genetic traits such as fearlessness in more dangerous directions—