54.4 Behavior Therapies

54-

663

The insight therapies assume that many psychological problems diminish as self-

Classical Conditioning Techniques

One cluster of behavior therapies derives from principles developed in Ivan Pavlov’s early twentieth-

Another example: If a claustrophobic fear of elevators is a learned aversion to being in a confined space, then might one unlearn that association by reconditioning to replace the fear response? Counterconditioning pairs the trigger stimulus (in this case, the enclosed space of the elevator) with a new response (relaxation) that is incompatible with fear. Two specific counterconditioning techniques—

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What might a psychodynamic therapist say about Mowrer’s therapy for bed-wetting? How might a behavior therapist reply?

A psychodynamic therapist might be more interested in helping the child develop insight about the underlying problems that have caused the bed-

Exposure TherapiesPicture this scene reported in 1924 by behaviorist psychologist Mary Cover Jones: Three-

As Peter begins his midafternoon snack, Jones introduces a caged rabbit on the other side of the huge room. Peter, eagerly munching away on his crackers and drinking his milk, hardly notices. On succeeding days, she gradually moves the rabbit closer and closer. Within two months, Peter is tolerating the rabbit in his lap, even stroking it while he eats. Moreover, his fear of other furry objects subsides as well, having been countered, or replaced, by a relaxed state that cannot coexist with fear (Fisher, 1984; Jones, 1924).

Unfortunately for those who might have been helped by her counterconditioning procedures, Jones’ story of Peter and the rabbit did not immediately become part of psychology’s lore. It was more than 30 years later that psychiatrist Joseph Wolpe (1958; Wolpe & Plaud, 1997) refined Jones’ technique into what are now the most widely used types of behavior therapies: exposure therapies, which expose people to what they normally avoid or escape (behaviors that get reinforced by reduced anxiety). Exposure therapies have them face their fear, and thus overcome their fear of the fear response itself. As people can habituate to the sound of a train passing their new apartment, so, with repeated exposure, can they become less anxiously responsive to things that once petrified them (Barrera et al., 2013; Foa et al., 2013).

664

One widely used exposure therapy is systematic desensitization. Wolpe assumed, as did Jones, that you cannot be simultaneously anxious and relaxed. Therefore, if you can repeatedly relax when facing anxiety-

Next, using progressive relaxation, the therapist would train you to relax one muscle group after another, until you achieve a blissful state of complete relaxation and comfort. Then the therapist would ask you to imagine, with your eyes closed, a mildly anxiety-

The therapist would progress up the constructed anxiety hierarchy, using the relaxed state to desensitize you to each imagined situation. After several sessions, you move to actual situations and practice what you had only imagined before, beginning with relatively easy tasks and gradually moving to more anxiety-

“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt First Inaugural Address, 1933

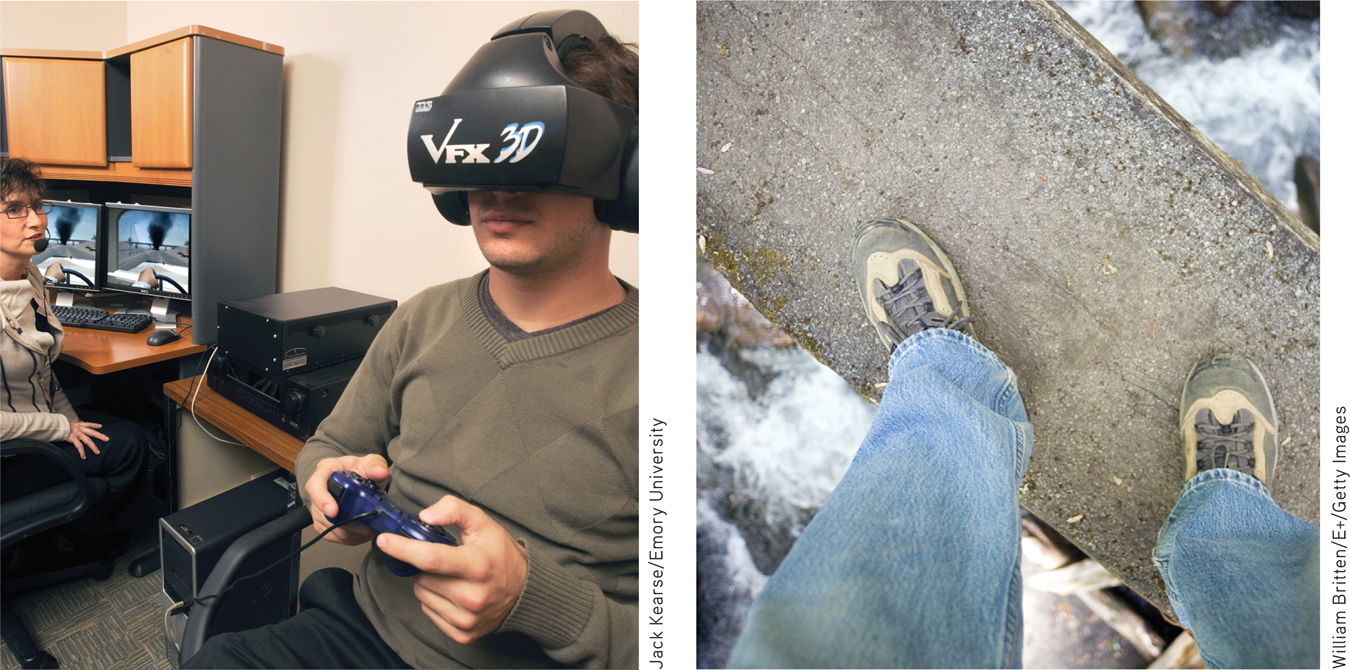

When an anxiety-

665

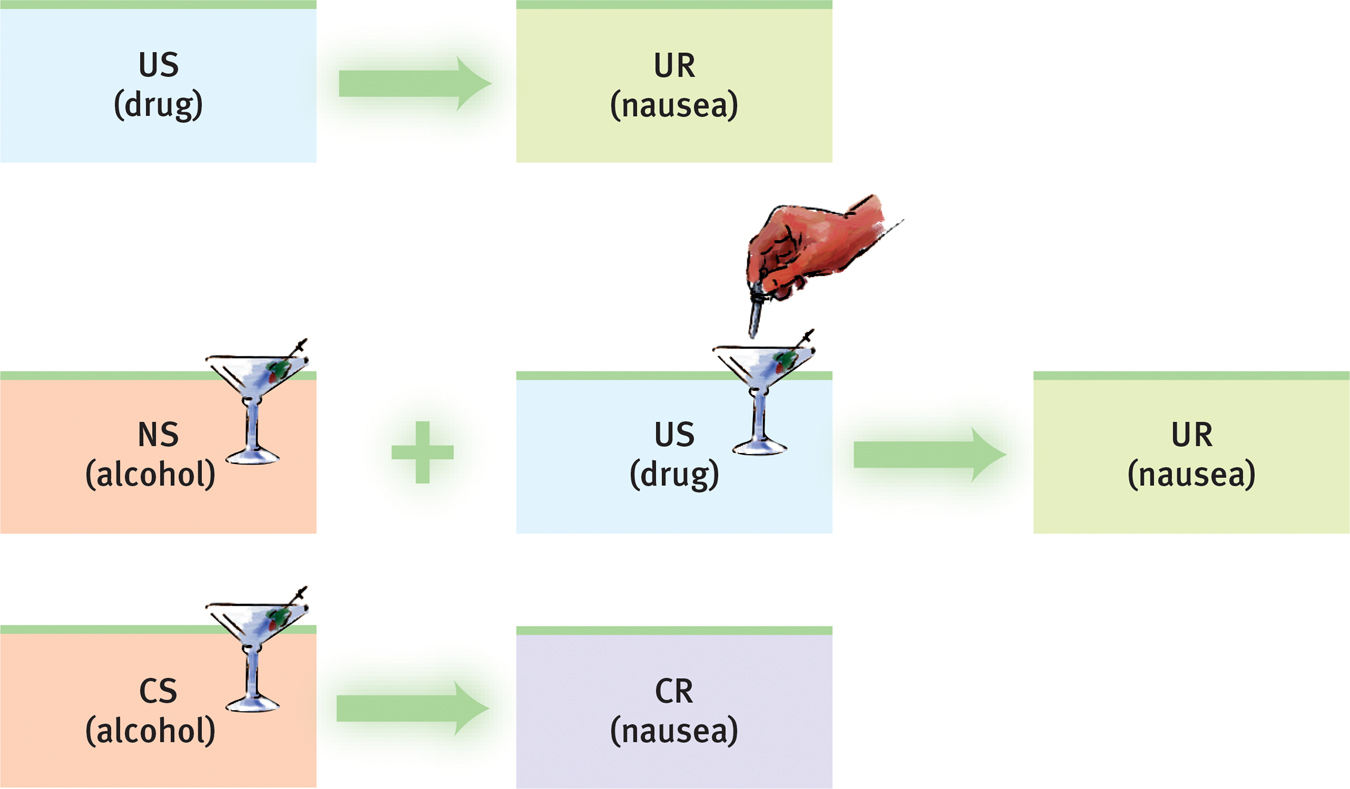

Aversive ConditioningIn systematic desensitization, the goal is substituting a positive (relaxed) response for a negative (fearful) response to a harmless stimulus. In aversive conditioning, the goal is substituting a negative (aversive) response for a positive response to a harmful stimulus (such as alcohol). Thus, aversive conditioning is the reverse of systematic desensitization—

The procedure is simple: It associates the unwanted behavior with unpleasant feelings. To treat nail biting, one can paint the fingernails with a nasty-

Figure 54.1

Figure 54.1Aversion therapy for alcohol use disorder After repeatedly imbibing an alcoholic drink mixed with a drug that produces severe nausea, some people with a history of alcohol use disorder develop at least a temporary conditioned aversion to alcohol. (Classical conditioning terms: US is unconditioned-

Does aversive conditioning work? In the short run it may. Arthur Wiens and Carol Menustik (1983) studied 685 hospital patients with alcohol use disorder who completed an aversion therapy program. One year later, after returning for several booster treatments of alcohol-

The problem is that in therapy (as in research), cognition influences conditioning. People know that outside the therapist’s office they can drink without fear of nausea. Their ability to discriminate between the aversive conditioning situation and all other situations can limit the treatment’s effectiveness. Thus, therapists often use aversive conditioning in combination with other treatments.

Operant Conditioning

54-

The work of B. F. Skinner and others teaches us a basic principle of operant conditioning: Voluntary behaviors are strongly influenced by their consequences. Knowing this, some behavior therapists practice behavior modification. They reinforce desired behaviors, and they withhold reinforcement for undesired behaviors. Using operant conditioning to solve specific behavior problems has raised hopes for some otherwise hopeless cases. Children with intellectual disabilities have been taught to care for themselves. Socially withdrawn children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have learned to interact. People with schizophrenia have been helped to behave more rationally in their hospital ward. In such cases, therapists use positive reinforcers to shape behavior in a step-

In extreme cases, treatment must be intensive. One study worked with 19 withdrawn, uncommunicative 3-

666

Rewards used to modify behavior vary. For some people, the reinforcing power of attention or praise is sufficient. Others require concrete rewards, such as food. In institutional settings, therapists may create a token economy. When people display appropriate behavior, such as getting out of bed, washing, dressing, eating, talking coherently, cleaning up their rooms, or playing cooperatively, they receive a token or plastic coin as a positive reinforcer. Later, they can exchange their accumulated tokens for various rewards, such as candy, TV time, trips to town, or better living quarters. Token economies have been successfully applied in various settings (homes, classrooms, hospitals, institutions for juvenile offenders) and among members of various populations (including disturbed children and people with schizophrenia and other mental disabilities).

Critics of behavior modification express two concerns. The first is practical: How durable are the behaviors? Will people become so dependent on extrinsic rewards that the appropriate behaviors will stop when the reinforcers stop? Proponents of behavior modification believe the behaviors will endure if therapists wean patients from the tokens by shifting them toward other, real-

The second concern is ethical: Is it right for one human to control another’s behavior? Those who set up token economies deprive people of something they desire and decide which behaviors to reinforce. To critics, this whole process has an authoritarian taint. Advocates reply that some patients request the therapy. Moreover, control already exists; rewards and punishers are already maintaining destructive behavior patterns. So why not reinforce adaptive behavior instead? Treatment with positive rewards is more humane than being institutionalized or punished, advocates argue, and the right to effective treatment and an improved life justifies temporary deprivation.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What are the insight-therapies, and how do they differ from behavior therapies?

The insight therapies—psychodynamic and humanistic therapies—

- Some maladaptive behaviors are learned. What hope does this fact provide?

If a behavior can be learned, it can be unlearned, and replaced by other more adaptive responses.

- Exposure therapies and aversive conditioning are applications of ___________ conditioning . Token economies are an application of __________ conditioning.

classical; operant