54.5 Cognitive Therapies

54-

We have seen how behavior therapists treat specific fears and problem behaviors. But how do they deal with depressive disorders? Or with generalized anxiety, in which anxiety has no focus? Behavior therapists treating these less clearly defined psychological problems have had help from the same cognitive revolution that has profoundly changed other areas of psychology during the last half-

“Life does not consist mainly, or even largely, of facts and happenings. It consists mainly of the storm of thoughts that are forever blowing through one’s mind.”

Mark Twain, 1835–1910

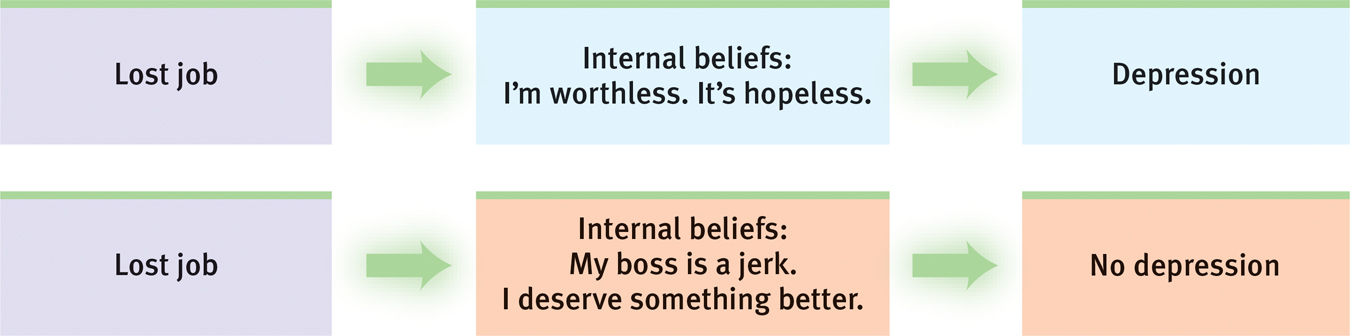

The cognitive therapies assume that our thinking colors our feelings (FIGURE 54.2). Between an event and our response lies the mind. Self-

Figure 54.2

Figure 54.2A cognitive perspective on psychological disorders The person’s emotional reactions are produced not directly by the event but by the person’s thoughts in response to the event.

Aaron Beck’s Therapy for Depression

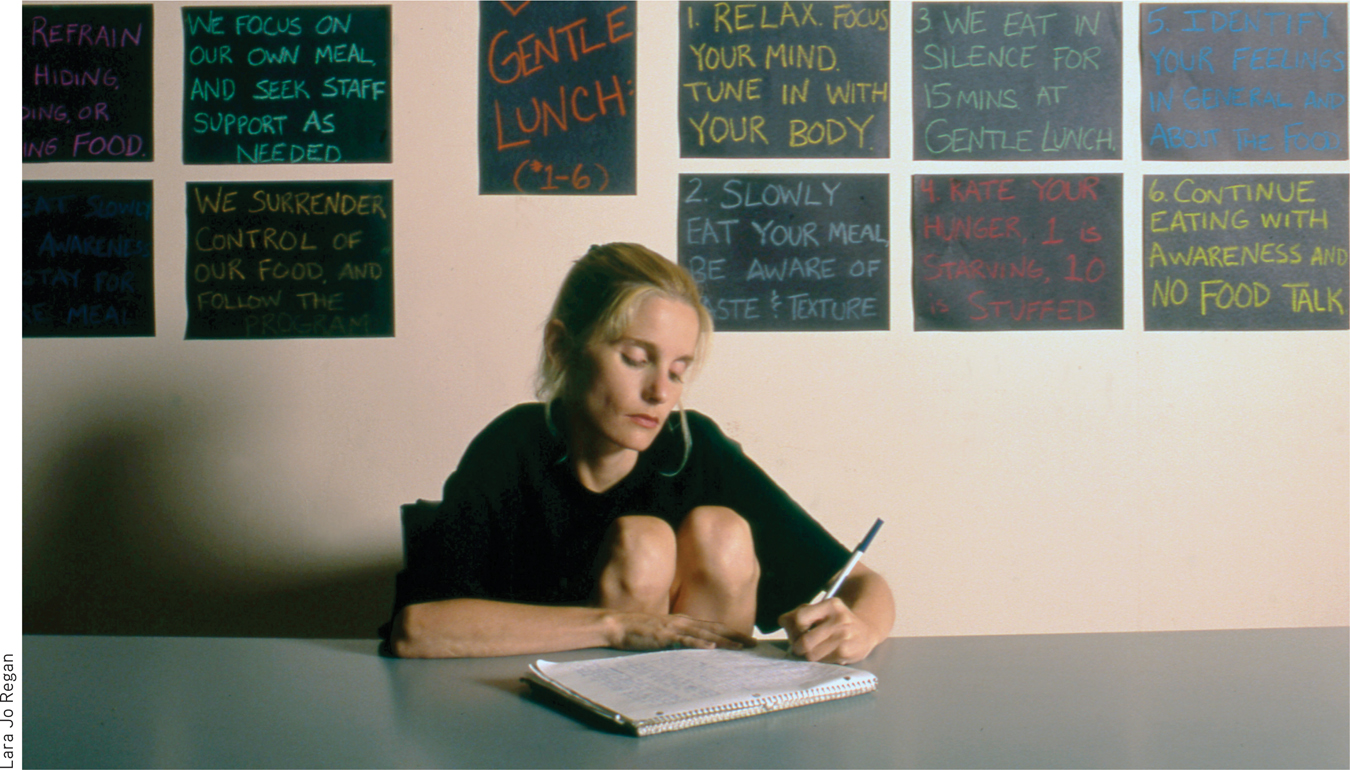

Cognitive therapist Aaron Beck believes that changing people’s thinking can change their functioning. When Beck analyzed depressed people’s dreams, he found recurring negative themes of loss, rejection, and abandonment that extended into their waking thoughts. Such negativity even extends into therapy, as clients recall and rehearse their failings and worst impulses (Kelly, 2000). With cognitive therapy, Beck and his colleagues (1979) sought to reverse clients’ catastrophizing beliefs about themselves, their situations, and their futures. Gentle questioning seeks to reveal irrational thinking, and then to persuade people to remove the dark glasses through which they view life (Beck et al., 1979, pp. 145–

Client: I agree with the descriptions of me but I guess I don’t agree that the way I think makes me depressed.

Beck: How do you understand it?

Client: I get depressed when things go wrong. Like when I fail a test.

Beck: How can failing a test make you depressed?

Client: Well, if I fail I’ll never get into law school.

Beck: So failing the test means a lot to you. But if failing a test could drive people into clinical depression, wouldn’t you expect everyone who failed the test to have a depression? … Did everyone who failed get depressed enough to require treatment?

Client: No, but it depends on how important the test was to the person.

Beck: Right, and who decides the importance?

Client: I do.

Beck: And so, what we have to examine is your way of viewing the test (or the way that you think about the test) and how it affects your chances of getting into law school. Do you agree?

Client: Right.

Beck: Do you agree that the way you interpret the results of the test will affect you? You might feel depressed, you might have trouble sleeping, not feel like eating, and you might even wonder if you should drop out of the course.

Client: I have been thinking that I wasn’t going to make it. Yes, I agree.

Beck: Now what did failing mean?

Client: (tearful) That I couldn’t get into law school.

Beck: And what does that mean to you?

Client: That I’m just not smart enough.

Beck: Anything else?

Client: That I can never be happy.

Beck: And how do these thoughts make you feel?

Client: Very unhappy.

Beck: So it is the meaning of failing a test that makes you very unhappy. In fact, believing that you can never be happy is a powerful factor in producing unhappiness. So, you get yourself into a trap—

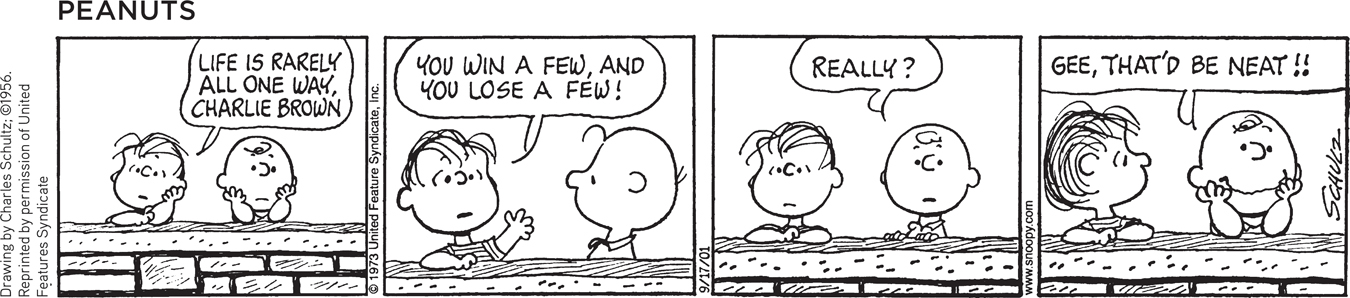

We often think in words. Therefore, getting people to change what they say to themselves is an effective way to change their thinking. Perhaps you can identify with the anxious students who, before an exam, make matters worse with self-

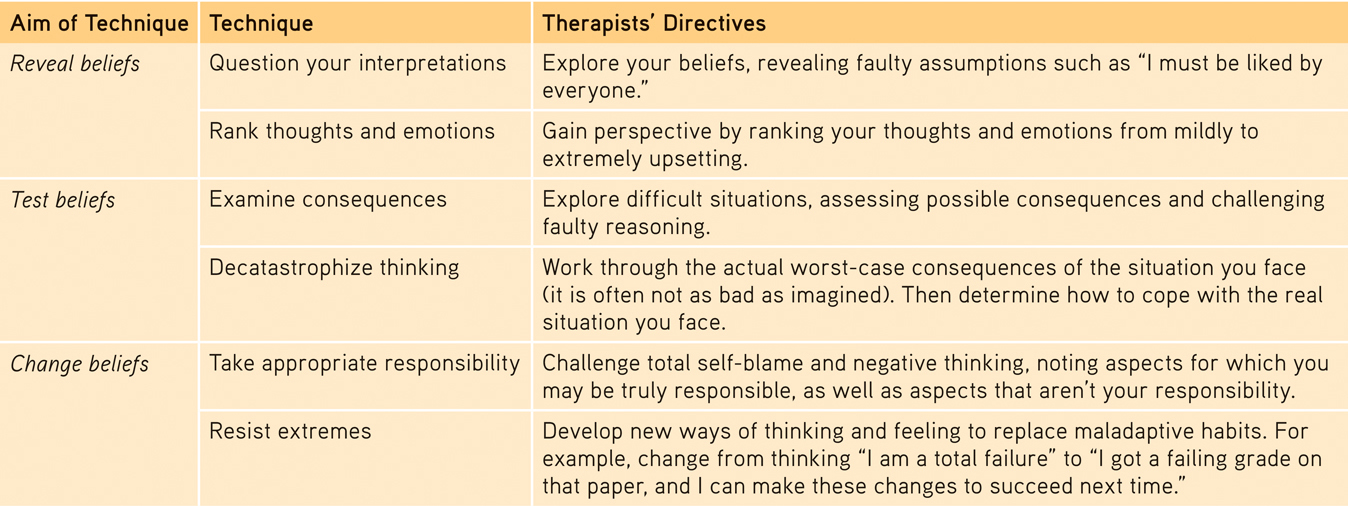

Table 54.1

Table 54.1Selected Cognitive Therapy Techniques

It’s not just depressed people who can benefit from positive self-

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) today’s most widely practiced psychotherapy, aims not only to alter the way people think (cognitive therapy), but also to alter the way they act (behavior therapy). It seeks to make people aware of their irrational negative thinking, to replace it with new ways of thinking, and to practice the more positive approach in everyday settings. Behavioral change is typically addressed first, followed by sessions on cognitive change; the therapy concludes with a focus on maintaining both and preventing relapses.

Anxiety, depressive disorders, and bipolar disorder share a common problem: emotion regulation (Aldao & Nolen-

“The trouble with most therapy is that it helps you to feel better. But you don’t get better. You have to back it up with action, action, action.”

Therapist Albert Ellis (1913–2007)

CBT may also be useful with obsessive-

Studies have also found that cognitive-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How do the humanistic and cognitive therapies differ?

By reflecting clients’ feelings in a nondirective setting, the humanistic therapies attempt to foster personal growth by helping clients become more self-

- An influential cognitive therapy for depression was developed by _________________ _________________.

Aaron Beck

- What is cognitive-behavioral therapy, and what sorts of problems does this therapy best address?

This integrative therapy helps people change self-