54.6 Group and Family Therapies

54-

Please continue to the next section.

Group Therapy

Except for traditional psychoanalysis, most therapies may also occur in small groups. Group therapy does not provide the same degree of therapist involvement with each client. However, it offers many benefits:

- It saves therapists’ time and clients’ money, often with no less effectiveness than individual therapy (Fuhriman & Burlingame, 1994).

- It offers a social laboratory for exploring social behaviors and developing social skills. Therapists frequently suggest group therapy for people experiencing frequent conflicts or whose behavior distresses others. For up to 90 minutes weekly, the therapist guides people’s interactions as they discuss issues and try out new behaviors.

- It enables people to see that others share their problems. It can be a relief to discover that you are not alone—to learn that others, despite their composure, experience some of the same troublesome feelings and behaviors.

- It provides feedback as clients try out new ways of behaving. Hearing that you look poised, even though you feel anxious and self-conscious, can be very reassuring.

Family Therapy

One special type of group interaction, family therapy, assumes that no person is an island: We live and grow in relation to others, especially our families. We struggle to differentiate ourselves from our families, but we also need to connect with them emotionally. Some of our problem behaviors arise from the tension between these two tendencies, which can create family stress.

Unlike most psychotherapy, which focuses on what happens inside the person’s own skin, family therapists work with multiple family members to heal relationships and to mobilize family resources. They tend to view the family as a system in which each person’s actions trigger reactions from others, and they help family members discover their role within their family’s social system. A child’s rebellion, for example, affects and is affected by other family tensions. Therapists also attempt—

Self-Help Groups

Many people also participate in self-

With more than 2 million members worldwide, AA is said to be “the largest organization on Earth that nobody wanted to join” (Finlay, 2000).

The grandparent of support groups, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), reports having 2.1 million members in 115,000 groups worldwide. Its famous 12-

In an individualistic age, with more and more people living alone or feeling isolated, the popularity of support groups—

***

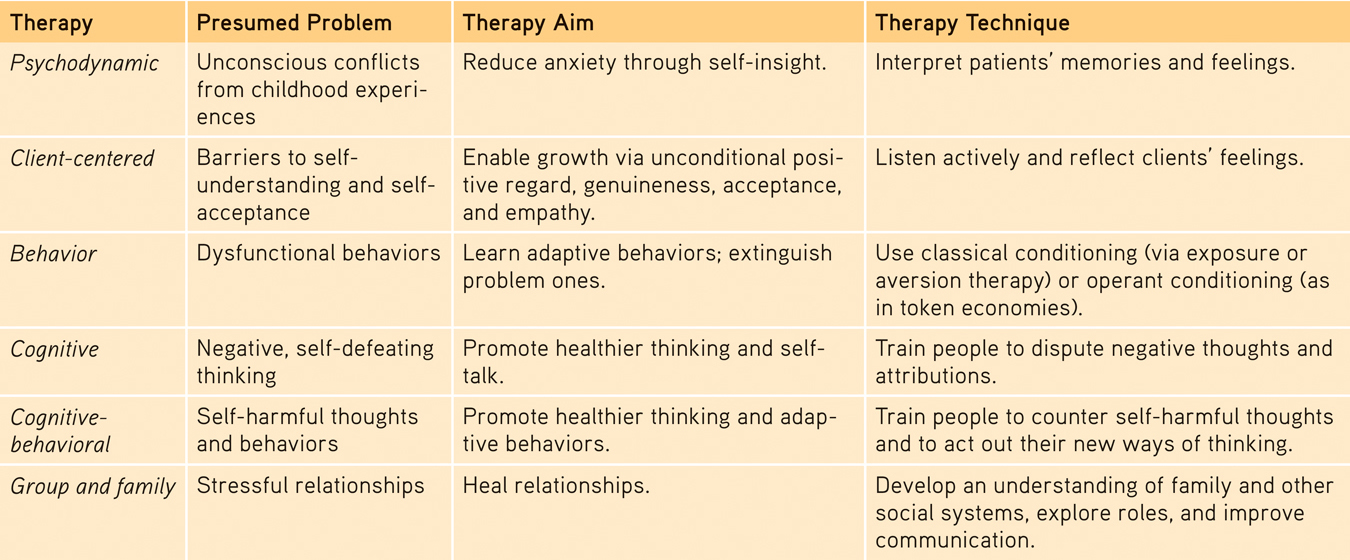

For a synopsis of the modern forms of psychotherapy we’ve been discussing, see TABLE 54.2.

Table 54.2

Table 54.2Comparing Modern Psychotherapies

To review the aims and techniques of different psychotherapies, and assess your ability to recognize excerpts from each, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Mystery Therapist.

To review the aims and techniques of different psychotherapies, and assess your ability to recognize excerpts from each, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Mystery Therapist.