55.1 Is Psychotherapy Effective?

55-

The question, though simply put, is not simple to answer. Measuring therapy’s effectiveness is not like taking your body’s temperature after a fever. So how can we assess psychotherapy’s effectiveness? By how we feel about our progress? By how our therapist feels about it? By how our friends and family feel about it? By how our behavior has changed?

Clients’ Perceptions

If clients’ testimonials were the only measuring stick, we could strongly affirm psycho-

We should not dismiss these testimonials. But for several reasons, client testimonials do not persuade psychotherapy’s skeptics:

- People often enter therapy in crisis. When, with the normal ebb and flow of events, the crisis passes, people may attribute their improvement to the therapy. Depressed people often get better no matter what they do.

- Clients believe that treatment will be effective. The placebo effect is the healing power of positive expectations.

- Clients want to believe the therapy was worth the effort. To admit investing time and money in something ineffective is like admitting to having one’s car serviced repeatedly by a mechanic who never fixes it. Self-

justification is a powerful human motive, which helps explain why all therapies produce appreciative testimonials.  Trauma: These women were mourning the tragic loss of lives and homes in the 2010 earthquake in China. Those who suffer through such trauma may benefit from counseling, though many people recover on their own or with the help of supportive relationships with family and friends. “Life itself still remains a very effective therapist,” noted psychodynamic therapist Karen Horney (Our-

Trauma: These women were mourning the tragic loss of lives and homes in the 2010 earthquake in China. Those who suffer through such trauma may benefit from counseling, though many people recover on their own or with the help of supportive relationships with family and friends. “Life itself still remains a very effective therapist,” noted psychodynamic therapist Karen Horney (Our-Inner- 1945).Conflicts, - Clients generally speak kindly of their therapists. Even if the problems remain, say the critics, clients “work hard to find something positive to say. The therapist had been very understanding, the client had gained a new perspective, he learned to communicate better, his mind was eased, anything at all so as not to have to say treatment was a failure” (Zilbergeld, 1983, p. 117).

As researchers continue to document, we are prone to selective and biased recall and to making judgments that confirm our beliefs. Consider the testimonials gathered in a massive experiment with over 500 Massachusetts boys, aged 5 to 13 years, many of whom seemed bound for delinquency. By the toss of a coin, half the boys were assigned to a 5-

Client testimonials were glowing. Some men noted that, had it not been for their counselors, “I would probably be in jail,” “My life would have gone the other way,” or “I think I would have ended up in a life of crime.” Court records offered apparent support: Even among the “difficult” boys in the treatment group, 66 percent had no official juvenile crime record.

But recall psychology’s most powerful tool for sorting reality from wishful thinking: the control group. For every boy in the treatment group, there was a similar boy in a control group, receiving no counseling. Of these untreated men, 70 percent had no juvenile record. On several other measures, such as a record of having committed a second crime, alcohol use disorder, death rate, and job satisfaction, the untreated men exhibited slightly fewer problems. The glowing testimonials of those treated had been unintentionally deceiving.

Clinicians’ Perceptions

Do clinicians’ perceptions give us any more reason to celebrate? Case studies of successful treatment abound. The problem is that clients justify entering psychotherapy by emphasizing their unhappiness and justify leaving by emphasizing their well-

Because people enter therapy when they are extremely unhappy, and usually leave when they are less unhappy, most therapists, like most clients, testify to therapy’s success—

Outcome Research

How, then, can we objectively measure the effectiveness of psychotherapy? How can we determine which people and problems are helped, and by what type of psychotherapy?

In search of answers, psychologists have turned to controlled research studies. Similar research in the 1800s transformed the field of medicine. Physicians, skeptical of many of the fashionable treatments (bleeding, purging, infusions of plant and metal substances), began to realize that many patients got better on their own, without these treatments, and that others died despite them. Sorting fact from superstition required observing patients with and without a particular treatment. Typhoid fever patients, for example, often improved after being bled, convincing most physicians that the treatment worked. Not until a control group was given mere bed rest—

In psychology, the opening challenge to the effectiveness of psychotherapy was issued by British psychologist Hans Eysenck (1952). Launching a spirited debate, he summarized studies showing that two-

Why, then, are we still debating psychotherapy’s effectiveness? Because Eysenck also reported similar improvement among untreated persons, such as those who were on waiting lists. With or without psychotherapy, he said, roughly two-

Later research revealed shortcomings in Eysenck’s analyses; his sample was small (only 24 studies of psychotherapy outcomes in 1952). Today, hundreds of studies are available. The best are randomized clinical trials, in which researchers randomly assign people on a waiting list to therapy or to no therapy, and later evaluate everyone, using tests and assessments by others who don’t know whether therapy was given. The results of many such studies are then digested by means of meta-analysis, a statistical procedure that combines the conclusions of a large number of different studies. Simply said, meta-

Therapists welcomed the first meta-

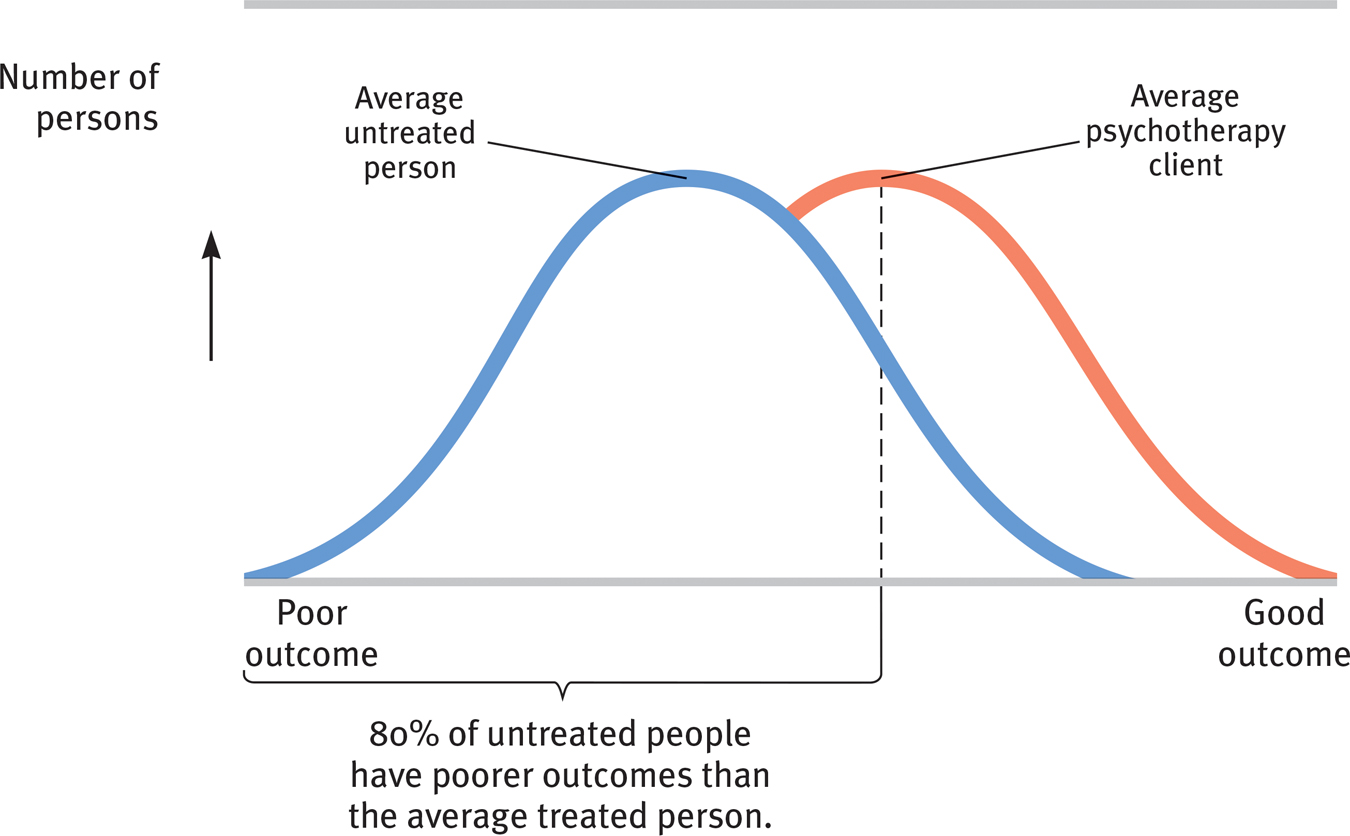

Figure 55.1

Figure 55.1Treatment versus no treatment These two normal distribution curves based on data from 475 studies show the improvement of untreated people and psychotherapy clients. The outcome for the average therapy client surpassed the outcome for 80 percent of the untreated people. (Data from Smith et al., 1980.)

Dozens of subsequent summaries have now examined psychotherapy’s effectiveness. Their verdict echoes the results of the earlier outcome studies: Those not undergoing therapy often improve, but those undergoing therapy are more likely to improve, and to improve more quickly and with less risk of relapse. Moreover, between treatment sessions for depression and anxiety, many people experience sudden symptom reductions. Those “sudden gains” bode well for long-

Is psychotherapy also cost-

But note that the claim—

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How might the placebo-effect bias clients’ and clinicians’ appraisals of the effectiveness of psychotherapies?

The placebo effect is the healing power of belief in a treatment. Patients and therapists who expect a treatment to be effective may believe it was.